The Carolingian Army and the Struggle Against the Vikings •

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paschasius Radbertus and the Song of Songs

chapter 6 “Love’s Lament”: Paschasius Radbertus and the Song of Songs The Song of Songs was understood by many Carolingian exegetes as the great- est, highest, and most obscure of Solomon’s three books of wisdom. But these Carolingian exegetes would also have understood the Song as a dialogue, a sung exchange between Christ and his church: in fact, as the quintessential spiritual song. Like the liturgy of the Eucharist and the divine office, the Song of Songs would have served as a window into heavenly realities, offering glimpses of a triumphant, spotless Bride and a resurrected, glorified Bridegroom that ninth- century reformers’ grim views of the church in their day would have found all the more tantalizing. For Paschasius Radbertus, abbot of the great Carolingian monastery of Corbie and as warm and passionate a personality as Alcuin, the Song became more than simply a treasury of imagery. In this chapter, I will be examining Paschasius’s use of the Song of Songs throughout his body of work. Although this is necessarily only a preliminary effort in understanding many of the underlying themes at work in Paschasius’s biblical exegesis, I argue that the Song of Songs played a central, formative role in his exegetical imagina- tion and a structural role in many of his major exegetical works. If Paschasius wrote a Song commentary, it has not survived; nevertheless, the Song of Songs is ubiquitous in the rest of his exegesis, and I would suggest that Paschasius’s love for the Song and its rich imagery formed a prism through which the rest of his work was refracted. -

"Years of Struggle": the Irish in the Village of Northfield, 1845-1900

SPRING 1987 VOL. 55 , NO. 2 History The GFROCE EDINGS of the VERMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY The Irish-born who moved into Northfield village arrived in impoverish ment, suffered recurrent prejudice, yet attracted other Irish to the area through kinship and community networks ... "Years of Struggle": The Irish in the Village of Northfield, 1845-1900* By GENE SESSIONS Most Irish immigrants to the United States in the nineteenth century settled in cities, and for that reason historians have focused on their experience in an urban-industrial setting. 1 Those who made their way to America's towns and villages have drawn less attention. A study of the settling-in process of nineteenth century Irish immigrants in the village of Northfield, Vermont, suggests their experience was similar, in im portant ways, to that of their urban counterparts. Yet the differences were significant, too, shaped not only by the particular characteristics of Northfield but also by adjustments within the Irish community itself. In the balance the Irish changed Northfield forever. The Irish who came into Vermont and Northfield in the nineteenth century were a fraction of the migration of nearly five million who left Ireland between 1845 and 1900. Most of those congregated in the cities along the eastern seaboard of the United States. Others headed inland by riverboats and rail lines to participate in settling the cities of the west. Those who traveled to Vermont were the first sizable group of non-English immigrants to enter the Green Mountain state. The period of their greatest influx was the late 1840s and 1850s, and they continued to arrive in declining numbers through the end of the century. -

Sears List of Subject Headings

Sears List of Subject Headings Sears List of Subject Headings 21st Edition BARBARA A. BRISTOW Editor CHRISTI SHOWMAN FARRAR Associate Editor H. W. Wilson A Division of EBSCO Information Services Ipswich, Massachusetts GREY HOUSE PUBLISHING 2014 Copyright © 2014, by H. W. Wilson, A Division of EBSCO Information Services, Inc.All rights reserved. No part of this work may be used or re- produced in any manner whatsoever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any in- formation storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. For subscription information, contact Grey House Pub- lishing, 4919 Route 22, PO Box 56, Amenia, NY 12501. For permissions requests, contact [email protected]. Abridged Dewey Decimal Classification and Relative Index, Edition 14 is © 2004- 2010 OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. Used with Permission. DDC, Dewey, Dewey Decimal Classification, and WebDewey are registered trademarks of OCLC. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Publisher’s Cataloging-In-Publication Data (Prepared by The Donohue Group, Inc.) Sears list of subject headings. – 21st Edition / Barbara A. Bristow, Editor; Christi Showman Farrar, Associate Editor. pages ; cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN: 978-1-61925-190-8 1. Subject headings. I. Bristow, Barbara A. II. Farrar, Christi Showman. III. Sears, Minnie Earl, 1873-1933. Sears list of subject headings. IV. H.W. Wilson Company. Z695.Z8 S43 2014 025.4/9 Contents Preface . vii Acknowledgments . xiii Principles of the Sears List . xv 1. The Purpose of Subject Cataloging. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

History Today Magazine, Vikings Warriors of No Nation

Norse travellers reached every corner of the known world, but they were not tourists. The ‘racially pure’ Vikings of stereotype were, in fact, cultural chameleons adopting local habits, languages and religions. Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough VIKINGS WARRIORS OF NO NATION Viking ship carrying Harold III of Norway against his half-brother Olaf II in 1030, c.1375. 2 | History Today | April 2018 April 2018 | History Today | 3 n January 2018, President Trump Odinism and white supremacy are bedfellows. expressed a preference for immigrants Such ideas of racial and cultural purity from affluent nations such as Norway, as would have been alien to the inhabitants of the opposed to those from what he termed medieval Nordic world. They may have come ‘shithole countries’. The indignant from the northernmost fringes of Europe – and Iresponse was on a global scale. Photos of in the case of Icelanders, in the middle of the beautiful African sunsets and wildlife were North Atlantic – but Norse travellers reached posted. One Norwegian woman tweeted: ‘We every corner of the known world. are not coming. Cheers from Norway.’ Trump was not the first to misuse Blond men in boats Scandinavian countries as a poster child for Thanks to chronicles and letters written by racism. The Nazi ideology of Aryan supremacy Christian holy men, perpetuated by modern rested on the premise of the Nordic race as books, cartoons and films, an enduring Viking superior to all others. Particularly disturbing stereotype is engrained in our collective was the ‘Lebensborn’ programme initiated by cultural imagination: blond men in boats with the head of the SS Heinrich Himmler to secure beards and battle-axes, sailing slate-grey seas the racial purity of the Third Reich. -

The Empire That Was Always Decaying: the Carolingians (800-888) Mayke De Jong*

The Empire that was always Decaying: The Carolingians (800-888) Mayke de Jong* This paper examines the potency of the concept of ›empire‹ in Carolingian history, arguing against the still recent trend in medieval studies of seeing the Carolingian empire as having been in a constant state of decay. An initial historiographical overview of medievalist’s perceptions of ›empire‹ over the past century is followed by a discussion of how Carolingian authors themselves constructed, perceived and were influenced by notions of ›empire‹. Bib- lical scholars like Hraban Maur initiated an authoritative discourse on imperium, which in turn, after the 840s, heavily influenced later authors, perhaps most interestingly Paschasius Radbertus in his Epitaphium Arsenii. While the writings of these authors who looked back at Louis’s reign have often been interpreted as revealing a decline of imperial ideals, they must rather be seen as testifying to a long-lasting concern for a universal Carolingian empire. Keywords: Carolingian empire; Historiography; imperium; Louis the Pious; Staatlichkeit. According to most textbooks, the first Western empire to succeed its late Roman predecessor suddenly burst upon the scene, on Christmas Day 800 in Rome, when Pope Leo III turned Charles, King of the Franks and Lombards, and patricius (protector) of the Romans, into an imperator augustus. Few events have been debated so much ad nauseam by modern histori- ans as this so-called imperial coronation of 800, which was probably not at all a coronation; contemporary sources contradict each other as to what happened on that Christmas Day in St. Peter’s church.1 Charlemagne’s biographer Einhard claimed that the vigorous Frankish king »would not have entered the church that day, even though it was a great feast day, if he had known in advance of the pope’s plan«. -

Vikings LEVELED READER • T a Reading A–Z Level T Leveled Reader Word Count: 1,359 VIKINGS

Vikings LEVELED READER • T A Reading A–Z Level T Leveled Reader Word Count: 1,359 VIKINGS Z T W Written by William Houseman Illustrated by Maria Voris Visit www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com for thousands of books and materials. VIKINGS Written by William Houseman Vikings Level T Leveled Reader Illustrated by Maria Voris © Learning A–Z, Inc. Correlation Written by William Houseman LEVEL T Illustrated by Maria Voris Fountas & Pinnell P All rights reserved. Reading Recovery 38 www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com DRA 38 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................... 4 Viking Warriors ................................................. 7 Discovering a New Land ............................... 10 Eric the Red ...................................................... 12 Leif Ericson ...................................................... 14 Other Viking Conquests ................................. 18 Glossary ............................................................ 20 INTRODUCTION When you hear the word Vikings, do you think of warriors or do you think of explorers? Do you think of merchants or do you think of poets? The Vikings were all of these things. They were also scientists, farmers, and fisherfolk. They were courageous fighters who loved to explore the world. 3 4 The Viking Age began about twelve hundred Over time, the Vikings’ spirit of exploration years ago. The Vikings came from the coastal and adventure led them to places all around lands in northern Europe that are now the Europe. It even led them to discover new countries of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. lands that no one in Europe knew existed. The Vikings were used to cold weather and They seized land along the western coast of learned to sail and fight at an early age. Their Europe. They even conquered land along the ships were fast and could carry many warriors. -

Download the “Freeview” Communication Software from Our Website

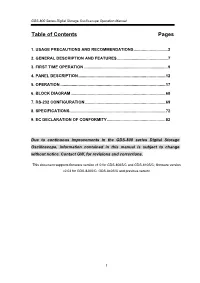

GDS-800 Series Digital Storage Oscilloscope Operation Manual Table of Contents Pages 1. USAGE PRECAUTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS..............................2 2. GENERAL DESCRIPTION AND FEATURES.............................................7 3. FIRST TIME OPERATION ..........................................................................9 4. PANEL DESCRIPTION .............................................................................12 5. OPERATION .............................................................................................17 6. BLOCK DIAGRAM....................................................................................68 7. RS-232 CONFIGURATION .......................................................................69 8. SPECIFICATIONS.....................................................................................72 9. EC DECLARATION OF CONFORMITY....................................................82 Due to continuous improvements in the GDS-800 series Digital Storage Oscilloscope, information contained in this manual is subject to change without notice. Contact GW, for revisions and corrections. This document supports firmware version v1.0 for GDS-806S/C and GDS-810S/C; firmware version v2.03 for GDS-820S/C, GDS-840S/C and previous version 1 GDS-800 Series Digital Storage Oscilloscope Operation Manual 1. Usage Precautions and Recommendations The following precautions are recommended to insure your safety and to provide the best condition of this instrument. If this equipment is used in a manner not specified -

Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775-831

Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editor Florin Curta VOLUME 16 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/ecee Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 By Panos Sophoulis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Cover illustration: Scylitzes Matritensis fol. 11r. With kind permission of the Bulgarian Historical Heritage Foundation, Plovdiv, Bulgaria. Brill has made all reasonable efforts to trace all rights holders to any copyrighted material used in this work. In cases where these efforts have not been successful the publisher welcomes communications from copyright holders, so that the appropriate acknowledgements can be made in future editions, and to settle other permission matters. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sophoulis, Pananos, 1974– Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 / by Panos Sophoulis. p. cm. — (East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450, ISSN 1872-8103 ; v. 16.) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-20695-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Byzantine Empire—Relations—Bulgaria. 2. Bulgaria—Relations—Byzantine Empire. 3. Byzantine Empire—Foreign relations—527–1081. 4. Bulgaria—History—To 1393. I. Title. DF547.B9S67 2011 327.495049909’021—dc23 2011029157 ISSN 1872-8103 ISBN 978 90 04 20695 3 Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

The History of the Monks of St Filibert in the Ninth Century

COMMUNITY, CULT AND POLITICS: THE HISTORY OF THE MONKS OF ST FILIBERT IN THE NINTH CENTURY Christian Harding A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/915 This item is protected by original copyright Community, cult and politics: the history of the monks of St Filibert in the ninth century. Christian Harding Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews June 2009 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews. Contents Acknowledgements i Abbreviations ii Maps viii Architectural plans xviii ONE: Introduction I: Historiography 1 II: Texts and movements 7 III: Aims of this study 10 TWO: Texts, authorship and dedications I: Introduction 17 II: Texts i: Dedicatory passages and De Translationibus et Miraculis Sancti Filiberti - Book one 18 ii: De Translationibus et Miraculis Sancti Filiberti - Book two 23 iii: The Chronicon Trenorchiense 24 iv: The Vita Filiberti 26 v: Ermentarius’ Vita Filiberti 36 III: Authorship 39 IV: Patrons i: Hilduin of Saint-Denis 43 ii: Charles the Bald 61 V: Conclusions 66 THREE: Noirmoutier to Déas I: Introduction 68 II: Northmen, Bretons and Carolingian politics i: Northmen 73 ii: Brittany and the Carolingian March 89 iii: Wala and Adalhard 104 III: Filibertine trade 115 IV: Architectural developments at Déas -

From Vikings to Welfare Early State Building and Social Trust in Scandinavia

From Vikings to Welfare Early State Building and Social Trust in Scandinavia (Gert Tinggaard Svendsen and Gunnar Lind Haase Svendsen, version 24-2-10) Abstract: The Scandinavian welfare states hold the highest social trust scores in the world. Why? Based on the stationary bandit model by Olson (1993), we first demonstrate that early state building during Viking Age facilitated public good provision and extensive trade. Social trust were probably not destroyed but rather accumulated in the following centuries up till the universal welfare state of the 20th century. Focusing on the case of Denmark, our tentative argument is that social trust was not destroyed through five subsequent phases of state building but rather enhanced. Long-run political stability arguably allows such a self-reinforcing process over time between institutions and social trust. Keywords Social trust, welfare state, Viking Age, Scandinavia, state building, plunder, trade. Total number of pages 21 Word count 6.850 1 1. Introduction Why does Scandinavia hold the highest social trust scores in the World? It is still unclear how the observed high level of social trust in the Scandinavian countries has been generated (Svendsen and Svendsen, 2009). Several competing explanations can be found in the literature. Putnam‟s explanation is that social trust is built bottom-up by ordinary citizens in voluntary, civic associations (Putnam 1993a). In recent years, Putnam‟s approach has been criticized for one-sidedness (e.g. Portes 1998; Kumlin & Rothstein 2005), or has simply been abandoned (e.g. Newton 2007; Bjørnskov 2009). This has given room for alternative explanations, such as the impact of socialization (e.g. -

Trip Description 6-Day Cycle Tour in the Vendee Country Along the Atlantic

Trip description 6-day cycle tour in the Vendee country along the Atlantic Enjoy the seaside in the Vendee country on this 6-day cycling holiday. You ride mostly on dedicated bike lanes on the Atlantic cycle route between Pornic and Les Sables d’Olonne. You will also appreciate to cycle on the island of Noirmoutier. Destination France Location Vendée Duration 6 days Difficulty Level Easy Validity From April 1st to Sept 30, 2021 Minimum age 12 years old Reference VO0401 Type of stay itinerant trip Itinerary Cycle 6 days along the Atlantic between Pornic and Les Sables d’Olonne and enjoy the charms of the Vendee coast. As you ride out of Pornic, you will be impressed by the landscape of the seaside from the corniche. The cycle route continues further along the Bourgneuf bay and then meanders through marshland. You overnight in the cute little village of Bouin and ride the next day to the island of Noirmoutier. Enjoy a unique experience riding to the island across the bay on a submersible road, the "passage du Gois" (only at low tide) or ride a longer route to take the bridge. You cycle further down the Atlantic coast through the pine forest to Saint-Jean-de-Monts. Your cycle holiday ends up in Les Sables d’Olonne, after a magnificent ride along the rocky coastline and through Saint-Gilles-Croix-de-Vie port and the Olonne marshland. Day 1 Arrival in Pornic Pornic is a charming port with a flair from Brittany. The town center is spreading on the hills surrounding the moorage, where boats are lying protected from the winds.