South Renfrewshire Access Network Initiative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Renfrewshire Case Study Harnessing Renfrewshire’S Watery Wealth Overview Who? Renfrewshire Council

Renfrewshire Case Study Harnessing Renfrewshire’s Watery Wealth Overview Who? Renfrewshire Council. What? Two hydro projects, a hydro and district heating strategy, and an ambitious plan to grow willow coppices as biomass fuel on derelict industrial sites. Where? Paisley, Lochwinnoch, Renfrewshire How much? £76, 780 (development grants in total). Background Water powered the industrial revolution in Renfrewshire – and it’s now making a comeback as part of ambitious plans to beat fuel poverty. The local The council is now conducting a feasibility study to authority is using almost £20,000 of grant money from see if they can harness the water at the weir to drive a the Warm Homes Fund to explore two potential small- turbine which would supply some of the power used at scale hydro sites for electrical power generation – one Renfrewshire House, where the majority of the council’s in the centre of one of Scotland’s largest towns and the staff are based. Money generated from Feed In Tariffs other near a pretty rural village. could then be used to create a community benefits fund to provide affordable warmth to households. Also on the cards is a forward-thinking scheme to grow willow trees on derelict industrial land around the region, then use the wood to fuel biomass boilers at council buildings, as well as selling any excess on the burgeoning “ At the moment we have several schemes renewable energy market. on the go using Warm Homes Fund money, which has been wonderfully easy to access.” Renfrewshire had hundreds of water-powered mills in the 18th century – they ran the textiles industry which Ron Mould, Energy Officer (Housing), Renfrewshire Council saw Paisley pattern cloth exported across the world. -

Ayrshire & Galloway

ARCH.,EOLOGICAL H ISTORICAL COLLtrCTIONS RELATING TO AYRSHIRE & GALLOWAY VOL. VII. EDINBURGH PRINTED FOR THE AYRSHIRE AND GALLOWAY ARCH.€OLOGICAL ASSOCIATION MDCCCXCIV !a't'j j..l I Pt'inted 6y Ii. €s" Il. Clarlt !'ott DAVID DOUGLAS, EDINBURGII 300 Copies lriruted, Of zu/aiclo tlais is Uo. 7, f ( AYRSHIRE AND GALLOUIAY ARCH.TOtOGICAL ASSOCIATION {D re 5itr e nt. Tnn EARL or STAIR, K.T., LL.D., LP.S.A. Scot., Iord.-Lieutenant of Ayrshire and Wigtonshire. zrlitv--ptviiU sntE, Tirn DUKE or PORTLAND. Tnn MARQUESS or BUTE, K.'I., LL.D., F;S.A. Scot. Tnn MARQUESS ol AILSA, F.S.A. Scot. Tun EARL ol GALLOWAY, K.T. Tltn EARL or GLASGOW. THs LORD HERRIES, Lord-Lieutenant of the Stewartry. Tnn Rr. HoN. SrnJAS. FERGUSSON, B.Enr.,M.P.,G.C.S.I.,K.C.M.G.,C.I.E., LL.D. Tun Rrcnr Hos. Srn J. DALRYMPLE -HAY, Bart., C.8., D.C.L., F.R.S. Srn M. SHAW-STEWART, BAnt., Lord-Lieutenant of Renfrewshire. Sm IMILLIAM J. MOI{TGOMERY-CUNINGIIAME, Banr., Y.C., bf Corsehill. Sm HERBERT EUSTACE MAXWELL, Banr., of Monreith, M.P., F.S.A. Scot. R. A. OSWALD, Esq., of Auchincui've. ilron- Secretsries tor Tvrsbite, R. \ry. COCHRAN-PATRICK, Esq., of Woodsicle, LL.D., F.S.A., F.S.A. Scot. Tsn Hon. HEW DALRYMPLE, tr'.S,A. Scot. (for Carrick). J. SHEDDEN-DOBIE, Est1., of Morishill, F.S.A. Scot (for Cuningharne). R. MUNRO, Esc1., ILD., M.A., F.S.A. Scot. bgn, Setretarieg for fuN,igtsnsbit.e, Tqn Rnv. -

Volume 21 Issue 4 August 2019

August 2019 Volume 21 Issue 4 www.stmacharsranfurlychurch.org.uk - 1 - Minister’s Letter A talented bunch If you were to list all the skills and In September we’ll be looking at participate in the £2 challenge talents of all of our church the topic of spiritual gifts; or (explained elsewhere). I also hope members, it would be a very long perhaps better called: gifts of the and pray that you will (re-)discover list indeed. We’ve got many Spirit. The Holy Spirit gives the gifts that the Spirit has given people, young and old, believers skills that are to be used you and you will use them for the contributing and using their gifts for the growth of the church. Paul building up of our church and time for the building up of the mentions quite a few in his letters, fellowship. As Paul explained to church – both in a physical and such as in 1 Corinthians 12. These the Corinthians; each one of us is spiritual sense. People visit, listen, are not for our own ‘glory’ but to needed and we all have a calling to give, bake, pray, welcome, read, be used for the building up of the exercise our gifts. sing, plan, fix, create, lead, teach fellowship; and we ourselves are You’ll be surprised to find how God and so on. Without people built up as we use them for one can use you! exercising their gifts and giving another. their time, there would be no So I hope you’ll come along to our Hanneke church. -

Records of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt

Records of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt HlUm'uiVi^mryTUFTS ii'S^Slt 024 287 G7 J83 Records of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt Records of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt COMPILED BY " TANTIVY » Author of " Scottish Hunts," and Contributor of Special Articles to "The Glasgow Herald" 1921 GLASGOW: PRINTED BY AIRD & COGHILL, LTD. PREFACE. ACTING upon the suggestion of the retiring Master and other prominent members of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt, I have ventured to produce an historical record which it is hoped will meet with the appreciation of those interested. For the description of the sport of the past twenty seasons I am greatly indebted to the diaries so perfectly kept by the late Mr. J. J. Barclay, which were kindly placed at my disposal by Mr. G. Barclay. Without such a valuable asset no work of this kind could ever have been attempted, and I have made the fullest possible use of these records, so that sportsmen and sportswomen of the last quarter of a century can refresh their memory in regard to the many great runs enjoyed during that period. I hope I have succeeded in an effort to furnish a complete and unvarnished account of the doings of the pack, together with a history of the Hunt since its origin. Possibly, at some future time, another enthusiast will take up the pen and bring the records up to date. Harry Judd (" Tantivy "). CONTENTS. PAGE The Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt, -------- 9 Group of Hounds in Kennel, 39 Presentation Ceremony at Finlaystone House, ------- 40 Meet at Barochan, -.-. -

Castle Semple, Lochwinnoch Castle Parkhill Wood Parkhill from “Heartlands” by Betty Mckellar, 1999 NCR7

Mature woodlands, distant views to the Firth of Clyde, a medievalCastle church, Semple, the traces of anLochwinnoch old formal estate, and a loch shore – this route certainly has plenty of variety. In Parkhill Wood you’ll see lots of changes with the passage of the seasons. Bluebells in spring, bright summer flowers, the rich reds and russets of autumn foliage, and bright winter berries attracting feeding birds. Enjoy it at any time of year ! Start and finish Castle Semple Visitor Centre, about 500m from the centre of Lochwinnoch (grid reference NS358590). There are signposts to the Centre in the village, which you can reach by public transport. Distance 8 km (5 miles). Allow 3 hours. Terrain Mixture of excellent flat paths and narrower woodland paths. Some muddy sections. No stiles but The golden finger of a solitary sunbeam shaft some gates. Shows silver silhouettes against the green Of poplar, hawthorn and ash And the slender birch, Ghosts adrift Like grey chiffon Floating in the wisps of twilight Castle Semple, Lochwinnoch Castle Parkhill Wood Parkhill from “Heartlands” by Betty McKellar, 1999 NCR7 5 7 8 3 6 4 9 2 1 Cycle routes N 0 0.2 miles 0 250 metres © Crown copyright. All rights reserved Renfrewshire Council O.S. licence RC100023417 2008. 1 From Castle Semple Visitor Centre car park, walk along the shore of Castle Semple Loch in front of the Centre building. Continue along the shore path. There are plenty of seats along here. 2 At a path junction with a lifebuoy and signboard, turn left up the hill. -

Renfrewshire Incapacity Benefit Claimant Profile

Scottish Observatory for Work and Health University of Glasgow Renfrewshire Incapacity Benefit Claimant Profile April 2010 Judith Brown Joel Smith David Webster James Arnott Ivan Turok Ewan Macdonald Richard Mitchell Contact: Judith Brown Public Health & Health Policy 1 Lilybank Gardens University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8RZ [email protected] 1 Summary & Key Findings Renfrewshire Incapacity Benefit claimant Profile 1. This incapacity benefit (IB) claimant profile for Renfrewshire gives detailed information on IB claimants by sex, age, reason for claiming IB and length of time on IB. It also contains IB claimant rates for the 38 intermediate zones in Renfrewshire (in 2008, Paisley Ferguslie had the highest IB rate at 23.1% and Houston South the lowest rate at 2.8%). 2. In 2008 there were 10,800 IB claimants in Renfrewshire. The IB rate, on flow rate and off flow rate were determined for Renfrewshire from 2000 to 2008. The percent of the working age population claiming IB has decreased from 12.3% to 10.2% from 2000 to 2008. The rate of on flow has decreased from 3.5% to 2.6% and the off flow rate has increased from 25.0% to 28.5%. 3. The proportion of ‘payment’ IB claimants is larger in Renfrewshire compared to Scotland for both males and females. The proportion of male and female ‘credits only’ IB claimants (those with a poor work history) have increased from 2000 to 2008. There are more female ‘credits only’ claimants than males in Renfrewshire. 4. The proportion of each age group who are claimants rises with age, peaking in the 60-64 age group. -

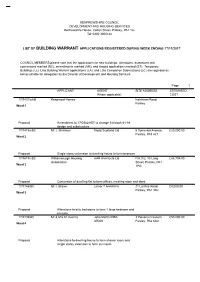

List of Building Warrant Applications Registered During Week Ending 17/11/2017

RENFREWSHIRE COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT AND HOUSING SERVICES Renfrewshire House, Cotton Street, Paisley, PA1 1LL Tel: 0300 3000144 LIST OF BUILDING WARRANT APPLICATIONS REGISTERED DURING WEEK ENDING 17/11/2017 COUNCIL MEMBERS please note that the applications for new buildings, alterations, extensions and conversions marked (BC); amendments marked (AM); and staged applications marked (ST); Temporary Buildings (LL); Late Building Warrant applications (LA); and Late Completion Submissions (LC) are regarded as being suitable for delegation by the Director of Development and Housing Services. Page 1 APPLICANT AGENT SITE ADDRESS ESTIMATED Where applicable) COST 17/1431/eAM Keepmoat Homes Inchinnan Road, Paisley Ward 1 Proposal Amendment to 17/0362/eST to change flat block 61-88 design and substructure 17/1415/eBC Mr J. Shannon Moda Scotland Ltd 8 Somerled Avenue, £20,000.00 Paisley, PA3 4JT Ward 2 Proposal Single storey extension to dwelling house to form bedroom 17/1619/eBC Williamsburgh Housing AHR Architects Ltd Flat 0/2, 10 Lang £43,759.00 Association Street, Paisley, PA1 Ward 3 1PG Proposal Conversion of dwelling flat to form offices, meeting room and store 17/1746/BC Mr J. Brown Linear 7 Architects 21 Lanfine Road, £9,000.00 Paisley, PA1 3NJ Ward 3 Proposal Alterations to attic bedrooms to form 1 large bedroom and en-suite 17/1739/BC Mr & Mrs M. Kearns John Martin RIBA 3 Polsons Crescent, £50,000.00 ARIAS Paisley, PA2 6AU Ward 4 Proposal Alterations to dwelling house to form shower room and single storey extension to form sun room Page 2 APPLICANT AGENT SITE ADDRESS ESTIMATED Where applicable) COST 17/1743/BC Glasgow Airport Limited Administration £1,800.00 Block, Arran Court, Ward 4 St Andrew's Drive, Glasgow Airport, Paisley, PA3 2ST Proposal Alterations to form power supplies for I.T. -

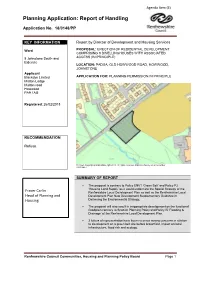

Planning Application: Report of Handling

Agenda Item (E) Planning Application: Report of Handling Application No. 18/0148/PP KEY INFORMATION Report by Director of Development and Housing Services Ward PROPOSAL: ERECTION OF RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT COMPRISING 9 DWELLINGHOUSES WITH ASSOCIATED 8 Johnstone South and ACCESS (IN PRINCIPLE) Elderslie LOCATION: PADUA, OLD HOWWOOD ROAD, HOWWOOD, JOHNSTONE Applicant Blackdye Limited APPLICATION FOR: PLANNING PERMISSION IN PRINCIPLE Midton Lodge Midton road Howwood PA9 1AG Registered: 26/02/2018 RECOMMENDATION Refuse. © Crown Copyright and database right 2013. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100023417. SUMMARY OF REPORT • The proposal is contrary to Policy ENV1 ‘Green Belt’ and Policy P2 ‘Housing Land Supply’ as it would undermine the Spatial Strategy of the Fraser Carlin Renfrewshire Local Development Plan as well as the Renfrewshire Local Head of Planning and Development Plan New Development Supplementary Guidance in Delivering the Environmental Strategy. Housing • The proposal will also result in inappropriate development on the functional floodplain contrary to Scottish Planning Policy and Policy I5 ‘Flooding & Drainage’ of the Renfrewshire Local Development Plan. • 3 letters of representation have been received raising concerns in relation to development on a green belt site before brownfield, impact on local infrastructure, flood risk and ecology. Renfrewshire Council Communities, Housing and Planning Policy Board Page 1 RENFREWSHIRE COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT AND HOUSING SERVICES REPORT OF HANDLING FOR APPLICATION 18/0148/PP APPLICANT: Blackdye Limited SITE ADDRESS: Padua, Old Howwood Road, Howwood, Johnstone, PA9 1AF PROPOSAL: Erection of residential development comprising 9 dwellinghouses with associated access (in principle). APPLICATION FOR: Planning Permission in Principle NUMBER OF Three letters of representation have been received. -

Inventory Acc.3721 Papers of the Scottish Secretariat and of Roland

Inventory Acc.3721 Papers of the Scottish Secretariat and of Roland Eugene Muirhead National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Summary of Contents of the Collection: BOXES 1-40 General Correspondence Files [Nos.1-1451] 41-77 R E Muirhead Files [Nos.1-767] 78-85 Scottish Home Rule Association Files [Nos.1-29] 86-105 Scottish National Party Files [1-189; Misc 1-38] 106-121 Scottish National Congress Files 122 Union of Democratic Control, Scottish Federation 123-145 Press Cuttings Series 1 [1-353] 146-* Additional Papers: (i) R E Muirhead: Additional Files Series 1 & 2 (ii) Scottish Home Rule Association [Main Series] (iii) National Party of Scotland & Scottish National Party (iv) Scottish National Congress (v) Press Cuttings, Series 2 * Listed to end of SRHA series [Box 189]. GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE FILES BOX 1 1. Personal and legal business of R E Muirhead, 1929-33. 2. Anderson, J W, Treasurer, Home Rule Association, 1929-30. 3. Auld, R C, 1930. 4. Aberdeen Press and Journal, 1928-37. 5. Addressall Machine Company: advertising circular, n.d. 6. Australian Commissioner, 1929. 7. Union of Democratic Control, 1925-55. 8. Post-card: list of NPS meetings, n.d. 9. Ayrshire Education Authority, 1929-30. 10. Blantyre Miners’ Welfare, 1929-30. 11. Bank of Scotland Ltd, 1928-55. 12. Bannerman, J M, 1929, 1955. 13. Barr, Mrs Adam, 1929. 14. Barton, Mrs Helen, 1928. 15. Brown, D D, 1930. -

Houston, Bridge of Weir, Brookfield, Kilbarchan, Howwood, Lochwinnoch & Elderslie Local Profile: Background Information

Houston, Bridge of Weir, Brookfield, Kilbarchan, Howwood, Lochwinnoch & Elderslie Local Profile: Background Information Population How many people live here? 27,344 people in total live in the area and below are the main concentrations of population: HOUSTON 6535 BRIDGE OF WEIR 4776 KILBARCHAN 3709 HOWWOOD 1798 LOCHWINNOCH 3436 BROOKFIELD 771 ELDERSLIE 6319 What age are people living here? Under Aged Aged 16 16-64 65+ Bridge of Weir 19% 60% 21% Elderslie and Phoenix 15% 63% 22% Houston North 19% 62% 19% Houston South 18% 65% 17% Kilbarchan 15% 61% 24% Lochwinnoch 17% 63% 20% Renfrewshire Rural South and 19% 62% 18% Howwood Overall 17% 62% 20% Please note figures may not add up to 100% because of rounding Villages 1 Local Profile Population Density Villages 2 Local Profile Children in Low Income Families As recorded by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation Villages 3 Local Profile The tables below are also taken from the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation and show other dimensions of deprivation: access, health and crime. The key below applies to the following three tables. Access Deprivation This measure includes drive time to GP, to retail centre, to petrol station, to primary and secondary schools, to post office and public transport time to GP, to retail centre, to post office. Villages 4 Local Profile Health Deprivation This measure includes the Standardised Mortality Ratio; Hospital stays related to alcohol misuse; Hospital stays related to drug misuse; Comparative Illness Factor; Emergency stays in hospital; Proportion of population being prescribed drugs for anxiety, depression or psychosis; and Proportion of live singleton births of low birth weight. -

Rivers and Streams Play an Important Part in the Recreation 6 Paisley Fulfil Conditions Under the Water Framework Directive and Is Being and Amenity Value of an Area

Current Status - UK and Local A wide variety of riverine habitats occurs in the LBAP Partnership area, ranging from fast flowing upland The River Calder feeds Castle Semple Loch with smaller contributions streams to slow flowing deep sections of river. In this area the main rivers are the White Cart Water, Black coming from the overflows of the Kilbirnie and Barr Lochs. Barr Loch Cart Water, Gryfe and Calder. They are relatively small rivers with the longest being the White Cart Water, was once a meadow with the Dubbs Water draining Kilbirnie Loch into which is 35km in length from its source south of Eaglesham to where it joins the Clyde Estuary at Renfrew. Castle Semple Loch. To preserve some of the marshy habitat in the There are also a number of tributaries that feed these rivers such as the Levern Water, Kittoch Water, Earn area, the Dubbs Water, which drains from Kilbirnie Loch, is channelled Water, Green Water, Dargavel Burn and Locher Water and some smaller watercourses such as the Spango around the outside of the Barr Loch. There is an opportunity to manage Burn. There is also a series of burns flowing down from the Clyde Muirshiel plateau. Land use in the area the area as seasonally flooded wetland (3 Lochs Project). To alleviate varies greatly - there is forest, moorland, agriculture, towns, villages, industrial areas, motorways and parks flooding in the vicinity of Calder Bridge, Lochwinnoch, excavation has amongst others, and each type of land use presents different problems and challenges for biodiversity and recently been carried out. -

The Semple Trail

DISCOVER THE SEMPLE TRAIL This belongs to: Use your passport to help you discover Can you work out the answers to all of all the Semple trail has to offer! these questions about the Trail? Get hands on with Learn to identify some of the many creatures these fun activities you’ll come across on the Semple Trail Learn all about the past and present of Keep your eyes peeled to find as many the Semple Trail with these fun facts of our resident creatures as you can THE LOCHSHORE ALONG FROM CASTLE SEMPLE For many years people have curled on the loch when it has frozen over. Lochwinnoch Curling Club was formed away back in 1827, and many big competitions were held in the area during the 19th century. Go and visit the curling rink ‘lookooterie’ just in front of Castle Semple Visitor Centre. Looking inside the rink will help you answer the following: How much does an Olympic curling stone weigh? In what year was curling first played at the winter Olympics? Lots of ducks and swans live at Castle Semple loch. How many can you see today? In Scottish Folklore, whooper swans are said to be a good omen. Here’s how you tell the difference between a whooper swan and a mute swan: WHOOPER SWANS have straight yellow beaks and whoop when in flight. What piece of equipment was said to be the first MUTE SWANS have orange beaks and a black used in Scotland to build a road between the Barr patch between their eyes.