Tyndale: on the Translation of 'Ecclesia' by Congregation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empty Tomb

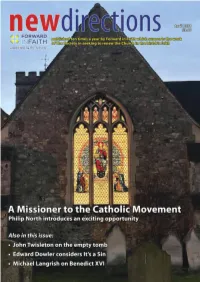

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900 Hancock, Christopher David How to cite: Hancock, Christopher David (1984) The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7473/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 VOLUME II 'THE PRIESTHOOD OF CHRIST IN ANGLICAN DOCTRINE AND DEVOTION: 1827 -1900' BY CHRISTOPHER DAVID HANCOCK The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Durham, Department of Theology, 1984 17. JUL. 1985 CONTENTS VOLUME. II NOTES PREFACE 1 INTRODUCTION 4 CHAPTER I 26 CHAPTER II 46 CHAPTER III 63 CHAPTER IV 76 CHAPTER V 91 CHAPTER VI 104 CHAPTER VII 122 CHAPTER VIII 137 ABBREVIATIONS 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 1 NOTES PREFACE 1 Cf. -

Life and Letters of Brooke Foss Westcott Vol. I

ST. mars couKE LIFE AND LETTERS OF BROOKE FOSS WESTCOTT Life and Letters of Foss Westcott Brooke / D.D., D.C.L. Sometime Bishop of Durham BY HIS SON ARTHUR WESTCOTT WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I 117252 ILonfcon MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1903 Ail rights reserved "To make of life one harmonious whole, to realise the invisible, to anticipate the transfiguring majesty of the Divine Presence, is all that is worth living for." B. F. \V. FRATRI NATU MAXIMO DOMUS NOSTRAE DUCI ET SIGNIFERO PATERNI NOMINIS IMPRIMIS STUDIOSO ET AD IPSIUS MEMORIAM SI OTIUM SUFFECISSET PER LITTERAS CELEBRANDAM PRAETER OMNES IDONEO HOC OPUSCULUM EIUS HORTATU SUSCEPTUM CONSILIIS AUCTUM ATQUE ADIUTUM D. D. D. FRATER NATU SECUNDUS. A. S., MCMIII. FRATKI NATU MAXIMO* 11ace tibi in re. ai<-o magni monnmcnta Parent is Maioi'i natu, frater, amo re pari. Si<jui'i inest dignnni, lactabere ; siquid ineptnm, Non milii tn censor sed, scio, [rater eris. Scis boif qnam duri fnerit res ilia laboris, Qnae melius per te suscipienda fiiit. 1 Tie diex, In nobis rcnoi'ali iwiinis /icres, Agtniw's ct nostri signifer unus eras. Scribcndo scd enim spatiiim, tibi sorte ncgatum, Iniporlnna minus fata dedcre mihi : Rt levin.: TISUDI cst infabrius arnia tulisse (Juain Patre pro tanto nil voluisse pati. lament: opus exaction cst quod, te sitadcnte, siibivi . Aecipc : indicia stctque cadatqne tno. Lcctorurn hand dnbia cst, reor, indulgentia. ; nalo Quodfrater frat ri tu dabis, ilia dabit. Xcc pctinins landcs : magnani depingerc vitani Ingcnio fatcor grandins ess.: nieo. Hoc erat in votis, nt, nos quod atnavinms, Hind Serns in cxtcrnis continnaret amor. -

Download 1 File

GHT tie 17, United States Code) r reproductions of copyrighted Ttain conditions. In addition, the works by means of various ents, and proclamations. iw, libraries and archives are reproduction. One of these 3r reproduction is not to be "used :holarship, or research." If a user opy or reproduction for purposes able for copyright infringement. to accept a copying order if, in its involve violation of copyright law. CTbc Minivers U^ of Cbicatjo Hibrcmes LIGHTFOOT OF DURHAM LONDON Cambridge University Press FETTER LANE NEW YORK TORONTO BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS Macmillan TOKYO Maruzen Company Ltd All rights reserved Phot. Russell BISHOP LIGHTFOOT IN 1879 LIGHTFOOT OF DURHAM Memories and Appreciations Collected and Edited by GEORGE R. D.D. EDEN,M Fellow Pembroke Honorary of College, Cambridge formerly Bishop of Wakefield and F. C. MACDONALD, M.A., O.B.E. Honorary Canon of Durham Cathedral Rector of Ptirleigb CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1933 First edition, September 1932 Reprinted December 1932 February PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN 1037999 IN PIAM MEMORIAM PATRIS IN DEO HONORATISSIMI AMANTISSIMI DESIDERATISSIMI SCHEDULAS HAS QUALESCUNQUE ANNOS POST QUADRAGINTA FILII QUOS VOCITABAT DOMUS SUAE IMPAR TRIBUTUM DD BISHOP LIGHTFOOT S BOOKPLATE This shews the Bishop's own coat of arms impaled^ with those of the See, and the Mitre set in a Coronet, indicating the Palatinate dignity of Durham. Though the Bookplate is not the Episcopal seal its shape recalls the following extract from Fuller's Church 5 : ense History (iv. 103) 'Dunelmia sola, judicat et stola. "The Bishop whereof was a Palatine, or Secular Prince, and his seal in form resembleth Royalty in the roundness thereof and is not oval, the badge of plain Episcopacy." CONTENTS . -

Chichester Diocesan Intercessions: July–September 2020

Chichester Diocesan Intercessions: J u l y – September 2020 JULY 10 Northern Indiana (The Episcopal Church) The Rt Revd Douglas 1 Sparks North Eastern Caribbean & Aruba (West Indies) The Rt Revd L. Bangor (Wales) The Rt Revd Andrew John Errol Brooks HIGH HURSTWOOD: Mark Ashworth, PinC; Joyce Bowden, Rdr; Attooch (South Sudan) The Rt Revd Moses Anur Ayom HIGH HURSTWOOD CEP SCHOOL: Jane Cook, HT; Sarah Haydon, RURAL DEANERY OF UCKFIELD: Paddy MacBain, RD; Chr Brian Porter, DLC 11 Benedict, c550 2 Northern Luzon (Philippines) The Rt Revd Hilary Ayban Pasikan North Karamoja (Uganda) The Rt Revd James Nasak Banks & Torres (Melanesia) The Rt Revd Alfred Patterson Worek Auckland (Aotearoa NZ & Polynesia) The Rt Revd Ross Bay Kagera (Tanzania) The Rt Revd Darlington Bendankeha Magwi (South Sudan) The Rt Revd Ogeno Charles Opoka MARESFIELD : Ben Sear, R; Pauline Ingram, Assoc.V; BUXTED and HADLOW DOWN: John Barker, I; John Thorpe, Rdr BONNERS CEP SCHOOL: Ewa Wilson, Head of School ST MARK’S CEP (Buxted & Hadlow Down) SCHOOL: Hayley NUTLEY: Ben Sear, I; Pauline Ingram, Assoc.V; Simpson, Head of School; Claire Rivers & Annette Stow, HTs; NUTLEY CEP SCHOOL: Elizabeth Peasgood, HT; Vicky Richards, Chr 3 St Thomas North Kigezi (Uganda) The Rt Revd Benon Magezi 12 TRINITY 5 Aweil (South Sudan) The Rt Revd Abraham Yel Nhial Pray for the Anglican Church of Papua New Guinea CHAILEY: Vacant, PinC; The Most Revd Allan Migi - Archbishop of Papua New Guinea ST PETERS CEP SCHOOL: Vacant, HT; Penny Gaunt, Chr PRAY for the Governance Team: Anna Quick; Anne-Marie -

Anglicanism and the British Empire, 1829-1910

Edinburgh Research Explorer Anglicanism and the British Empire, 1829-1910 Citation for published version: Brown, S 2017, Anglicanism and the British Empire, 1829-1910. in R Strong (ed.), The Oxford History of Anglicanism: Partisan Anglicanism and its Global Expansion, 1829-c.1914 . vol. III, Oxford History of Anglicanism, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 45-68. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The Oxford History of Anglicanism Publisher Rights Statement: Brown, S. (2017). Anglicanism and the British Empire, 1829-1910. In R. Strong (Ed.), The Oxford History of Anglicanism: Partisan Anglicanism and its Global Expansion, 1829-c.1914 . (Vol. III, pp. 45-68). (Oxford History of Anglicanism). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Anglicanism in the British Empire, 1829-1910 Stewart J Brown In 1849, Daniel Wilson, the Evangelical Anglican bishop of Calcutta and metropolitan of India, published a Charge to his clergy. -

The Commemoration of Founders and Benefactors at the Heart of Durham: City, County and Region

The Commemoration of Founders and Benefactors at the heart of Durham: City, County and Region Address: Professor Stuart Corbridge Vice-Chancellor University of Durham Sunday 22 November 2020 3.30 p.m. VOLUMUS PRÆTEREA UT EXEQUIÆ SINGULIS ANNIS PERPETUIS TEMPORIBUS IN ECCLESIA DUNELMENSI, CONVOCATIS AD EAS DECANO OMNIBUS CANONICIS ET CÆTERIS MINISTRIS SCHOLARIBUS ET PAUPERIBUS, PRO ANIMABUS CHARISSIMORUM PROGENITORUM NOSTRORUM ET OMNIUM ANTIQUI CŒNOBII DUNELMENSIS FUNDATORUM ET BENEFACTORUM, VICESIMO SEPTIMO DIE JANUARII CUM MISSÂ IN CRASTINO SOLENNITER CELEBRENTUR. Moreover it is our will that each year for all time in the cathedral church of Durham on the twenty-seventh day of January, solemn rites of the dead shall be held, together with mass on the following day, for the souls of our dearest ancestors and of all the founders and benefactors of the ancient convent of Durham, to which shall be summoned the dean, all the canons, and the rest of the ministers, scholars and poor men. Cap. 34 of Queen Mary’s Statutes of Durham Cathedral, 1554 Translated by Canon Dr David Hunt, March 2014 2 Welcome Welcome to the annual commemoration of Founders and Benefactors. This service gives us an opportunity to celebrate those whose generosity in the past has enriched the lives of Durham’s great institutions today and to look forward to a future that is full of opportunity. On 27 January 1914, the then Dean, Herbert Hensley Henson, revived the Commemoration of Founders and Benefactors. It had been written into the Cathedral Statutes of 1554 but for whatever reason had not been observed for centuries. -

Copyright © 2012 Matthew Scott Wireman All Rights Reserved. the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary Has Permission to Reprodu

Copyright © 2012 Matthew Scott Wireman All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. THE SELF-ATTESTATION OF SCRIPTURE AS THE PROPER GROUND FOR SYSTEMATIC THEOLOGY ___________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary ___________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ___________ by Matthew Scott Wireman December 2012 APPROVAL SHEET THE SELF-ATTESTATION OF SCRIPTURE AS THE PROPER GROUND FOR SYSTEMATIC THEOLOGY Matthew Scott Wireman Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Stephen J. Wellum (Chair) __________________________________________ Michael A. G. Haykin __________________________________________ Chad Owen Brand Date ______________________________ To Ashley, Like a lily among thorns, so is my Beloved among the maidens. Song of Songs 2:2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . x Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 Thesis . 2 The Historical Context for the Doctrine . 5 The Current Evangelical Milieu . 15 Methodology . 18 2. A SELECTIVE AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF SCRIPTURE’S SELF-WITNESS . 31 Patristic Period . 32 Reformation . 59 Post-Reformation and the Protestant Scholastics . 74 Modern . 82 Conclusion . 95 3. A SUMMARY AND EVALUATION OF THE POST-FOUNDATIONAL THEOLOGICAL METHOD OF STANLEY J. GRENZ AND JOHN R. FRANKE . 97 Introduction . 97 iv Denying Foundationalism and the Theological Method’s Task . 98 The Spirit’s Scripture . 116 Pannenbergian Coherentism and Eschatological Expectation . 123 Situatedness . 128 Communal Key . 131 Conclusion . 141 4. THE OLD TESTAMENT PARADIGM OF YHWH’S WORD AND HIS PEOPLE . 144 Sui Generis: “God as Standard in His World” . -

LIGHTFOOT, JOSEPH BARBER, 1828-1889. Joseph Barber Lightfoot Collection, 1881-1886

LIGHTFOOT, JOSEPH BARBER, 1828-1889. Joseph Barber Lightfoot collection, 1881-1886 Emory University Pitts Theology Library 1531 Dickey Drive, Suite 560 Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-4166 Descriptive Summary Creator: Lightfoot, Joseph Barber, 1828-1889. Title: Joseph Barber Lightfoot collection, 1881-1886 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 180 Extent: 0.5 cubic feet. (1 box) Abstract: Consists of two letters, one licensing document, and one printed portrait of Joseph Barber Lightfoot, Bishop of Durham. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Joseph Barber Lightfoot collection, Archives and Manuscript Dept., Pitts Theology Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Brandon Wason, November 2015. Collection Description Biographical Note Joseph Barber Lightfoot (1828-89) was an influential biblical scholar and clergyman in the church of England. He was born in Liverpool in 1828. He entered Trinity College, Cambridge in 1847, and became a tutor at Trinity College (1857). Lightfoot was appointed to the Hulsean Chair of Divinity (1861) and later became Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity (1875). His ecclesiastical career began in 1854 when he was ordained as a deacon. In 1858 he was ordained Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Church of England Licensing Document, 1886 Manuscript Collection No. 180 as a priest. His reputation as a preacher and clergyman soon matched his reputation as a scholar. -

The Gospel of John in Modern Interpretation Is a Wonderful Intro- Duction to the Fascinating World That Is the New Testament Study of John’S Gospel

“The Gospel of John in Modern Interpretation is a wonderful intro- duction to the fascinating world that is the New Testament study of John’s gospel. Tracing the general history of the gospel’s treatment, and focusing on the contribution of several key scholars, this book also traces the discussions that drive the gospel’s study and how best to read it. The gospel of John has been an outlier in Jesus studies. This work explains why that should not be so, and what one must pay attention to in reading this crucial gospel. It is well worth a careful read.” —Darrell L. Bock, Senior Research Professor of New Testament Studies, Dallas Theological Seminary “This is a very worthwhile volume, because instead of viewing ‘modern interpretation’ as an abstraction, it looks at eight, carefully chosen modern interpreters, with their whole careers and scholarly contribu- tions in view—not merely their work on John’s gospel. Three of them (Rudolf Bultmann, C. H. Dodd, and Raymond E. Brown) are obvious choices. Five others have been either half-forgotten (B. F. Westcott), unfairly neglected or underappreciated (Adolf Schlatter and Leon Morris), dismissed as idiosyncratic (John A. T. Robinson), or pigeon- holed as a ‘mere’ literary critic (R. Alan Culpepper). They all deserve better, and this collection calls attention, once again, to their substan- tial contributions. A much needed and promising correction. Thank you, Stan Porter and Ron Fay, and your authors!” —J. Ramsey Michaels, Professor of Religious Studies Emeritus, Missouri State University, Springfield “Here is an extremely well-chosen collection of vignettes of major Johannine scholars from the late 1800s to the present. -

Sunday 8 August 2021

DURHAM CATHEDRAL THE SHRINE OF ST CUTHBERT 26 JULY - 1 AUGUST 2021 Morning and Evening Prayer, Evensong and the Sunday service at 10.00 a.m. are live-streamed on the Cathedral’s Facebook page unless otherwise indicated. We strongly advise people to wear face coverings at all services unless you are exempt on health grounds. For weekday services, you are advised to bring your own books or use the Church of England’s Daily Prayer app on your various devices. When you attend a service, you will be encouraged to sign in with a QR code if you are able to do so. MONDAY 26 8.30 Morning Prayer 5.15 Evening Prayer 12.30 Holy Communion Benedict Altar Anne and Joachim, President: Canon Dorothy Snowball Parents of the Blessed Virgin Mary TUESDAY 27 8.30 Morning Prayer 5.15 Evening Prayer 12.30 Holy Communion Benedict Altar Brooke Foss Westcott, President: The Reverend Alan Middleton Bishop of Durham, Teacher, 1901 WEDNESDAY 28 8.30 Morning Prayer 5.15 Evening Prayer 12.30 Holy Communion Benedict Altar President: The Reverend Martin Saunders THURSDAY 29 8.30 Morning Prayer 5.15 Evening Prayer 12.30 Holy Communion Benedict Altar Mary, Martha and President: The Reverend David Grieve Lazarus, Companions of Our Lord FRIDAY 30 8.30 Morning Prayer and Litany 5.15 Evening Prayer 12.30 Holy Communion Benedict Altar William Wilberforce, President: The Reverend Margaret Devine Social Reformer, Olaudah Equiano and Thomas Clarkson, Anti-Slavery Campaigners, 1833, 1797 and 1846 SATURDAY 31 8.30 Morning Prayer 5.15 Evening Prayer 12.30 Holy Communion Benedict Altar -

J. B. Lightfoot (Died 1889), Commentator and Theologian Professor Bruce Continues Our Series on Topics in Historical Theology

HISTORICAL THEOLOGY J. B. Lightfoot (died 1889), Commentator and Theologian Professor Bruce continues our series on topics in Historical Theology Joseph Barber Lightfoot was born in Liverpool in 1828. His historical sources. Only four of the Pauline Epistles (I and II family moved to Birmingham, where (from 1844) he was edu Corinthians, Galatians and Romans) and the the Apocalypse cated at King Edward School, under the headmastership of could be dated in the apostolic age. The remaining New testament James Prince Lee, later first Bishop of Manchester. At school, he books reflected a time when the tensions of the apostolic age had formed a lifelong friendship with E. W. Benson (destined to been resolved, and this (according to Baur) could not well be become Archbishop of Canterbury). earlier than the middle of the second century. Now Clement of Rome, Ignatius and Polycarp all flourished before the middle of In 1847 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where one of his the second century, and to all of them are ascribed letters still classical tutors was Brooke Foss Westcott, his senior by only extant which presuppose some at least of the New Testament three years (and himself a former pupil of King Edward School, writings. Ignatius is specially important: he met his deatl} in the Birmingham). He took a double First (in classics and mathemat principipate of Trajan (ao 98-117), and the letters which have ics) and, in 1852, was elected a Fellow of Trinity, becoming a come down under his name reflect a stage of church life and tutor in the college five years later.