The Gospel of John in Modern Interpretation Is a Wonderful Intro- Duction to the Fascinating World That Is the New Testament Study of John’S Gospel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empty Tomb

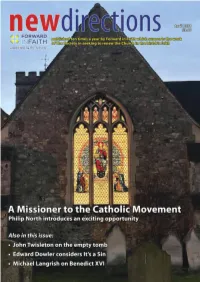

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900 Hancock, Christopher David How to cite: Hancock, Christopher David (1984) The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7473/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 VOLUME II 'THE PRIESTHOOD OF CHRIST IN ANGLICAN DOCTRINE AND DEVOTION: 1827 -1900' BY CHRISTOPHER DAVID HANCOCK The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Durham, Department of Theology, 1984 17. JUL. 1985 CONTENTS VOLUME. II NOTES PREFACE 1 INTRODUCTION 4 CHAPTER I 26 CHAPTER II 46 CHAPTER III 63 CHAPTER IV 76 CHAPTER V 91 CHAPTER VI 104 CHAPTER VII 122 CHAPTER VIII 137 ABBREVIATIONS 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 1 NOTES PREFACE 1 Cf. -

Life and Letters of Brooke Foss Westcott Vol. I

ST. mars couKE LIFE AND LETTERS OF BROOKE FOSS WESTCOTT Life and Letters of Foss Westcott Brooke / D.D., D.C.L. Sometime Bishop of Durham BY HIS SON ARTHUR WESTCOTT WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I 117252 ILonfcon MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1903 Ail rights reserved "To make of life one harmonious whole, to realise the invisible, to anticipate the transfiguring majesty of the Divine Presence, is all that is worth living for." B. F. \V. FRATRI NATU MAXIMO DOMUS NOSTRAE DUCI ET SIGNIFERO PATERNI NOMINIS IMPRIMIS STUDIOSO ET AD IPSIUS MEMORIAM SI OTIUM SUFFECISSET PER LITTERAS CELEBRANDAM PRAETER OMNES IDONEO HOC OPUSCULUM EIUS HORTATU SUSCEPTUM CONSILIIS AUCTUM ATQUE ADIUTUM D. D. D. FRATER NATU SECUNDUS. A. S., MCMIII. FRATKI NATU MAXIMO* 11ace tibi in re. ai<-o magni monnmcnta Parent is Maioi'i natu, frater, amo re pari. Si<jui'i inest dignnni, lactabere ; siquid ineptnm, Non milii tn censor sed, scio, [rater eris. Scis boif qnam duri fnerit res ilia laboris, Qnae melius per te suscipienda fiiit. 1 Tie diex, In nobis rcnoi'ali iwiinis /icres, Agtniw's ct nostri signifer unus eras. Scribcndo scd enim spatiiim, tibi sorte ncgatum, Iniporlnna minus fata dedcre mihi : Rt levin.: TISUDI cst infabrius arnia tulisse (Juain Patre pro tanto nil voluisse pati. lament: opus exaction cst quod, te sitadcnte, siibivi . Aecipc : indicia stctque cadatqne tno. Lcctorurn hand dnbia cst, reor, indulgentia. ; nalo Quodfrater frat ri tu dabis, ilia dabit. Xcc pctinins landcs : magnani depingerc vitani Ingcnio fatcor grandins ess.: nieo. Hoc erat in votis, nt, nos quod atnavinms, Hind Serns in cxtcrnis continnaret amor. -

Craig Blomberg, "Eschatology and the Church: Some New Testament

Craig Blomberg, “Eschatology and the Church’: Some New Testament Perspectives,” Themelios 23.3 (June 1998): 3-26. Eschatology and the Church1: Some New Testament Perspectives Craig Blomberg Professor of New Testament at Denver Seminary in Colorado and North American Review Editor for Themelios. [p.3] For many in the church today, eschatology seems to be one of the least relevant of the historic Christian doctrines. On the one hand, those who question the possibility of the supernatural in a scientific age find the cataclysmic irruption of God’s power into human history at the end of the ages unpalatable. On the other hand, notable fundamentalists have repeatedly put forward clear-cut apocalyptic scenarios correlating current events with the signs of the end in ways which have been repeatedly disproved by subsequent history and which have tarnished all conservative Christian expectation in the process as misguided.2 At the same time, a substantial amount of significant scholarship, particularly in evangelical circles, goes largely unnoticed by the church of Jesus Christ at large. This scholarship not only addresses key theological and exegetical cruxes but has direct relevance for Christian living on the threshold of the twenty-first century. The topic is immense, so before I proceed I need to make several disclaimers and mark out the parameters of this brief study: 1. I am neither a systematic theologian nor an OT specialist, so, as my title indicates, my comments will be primarily limited to those who have grappled with key themes and texts in the NT. In this connection I have sometimes ventured an opinion on a range of questions which I know require more careful and sustained consideration. -

Download 1 File

GHT tie 17, United States Code) r reproductions of copyrighted Ttain conditions. In addition, the works by means of various ents, and proclamations. iw, libraries and archives are reproduction. One of these 3r reproduction is not to be "used :holarship, or research." If a user opy or reproduction for purposes able for copyright infringement. to accept a copying order if, in its involve violation of copyright law. CTbc Minivers U^ of Cbicatjo Hibrcmes LIGHTFOOT OF DURHAM LONDON Cambridge University Press FETTER LANE NEW YORK TORONTO BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS Macmillan TOKYO Maruzen Company Ltd All rights reserved Phot. Russell BISHOP LIGHTFOOT IN 1879 LIGHTFOOT OF DURHAM Memories and Appreciations Collected and Edited by GEORGE R. D.D. EDEN,M Fellow Pembroke Honorary of College, Cambridge formerly Bishop of Wakefield and F. C. MACDONALD, M.A., O.B.E. Honorary Canon of Durham Cathedral Rector of Ptirleigb CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1933 First edition, September 1932 Reprinted December 1932 February PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN 1037999 IN PIAM MEMORIAM PATRIS IN DEO HONORATISSIMI AMANTISSIMI DESIDERATISSIMI SCHEDULAS HAS QUALESCUNQUE ANNOS POST QUADRAGINTA FILII QUOS VOCITABAT DOMUS SUAE IMPAR TRIBUTUM DD BISHOP LIGHTFOOT S BOOKPLATE This shews the Bishop's own coat of arms impaled^ with those of the See, and the Mitre set in a Coronet, indicating the Palatinate dignity of Durham. Though the Bookplate is not the Episcopal seal its shape recalls the following extract from Fuller's Church 5 : ense History (iv. 103) 'Dunelmia sola, judicat et stola. "The Bishop whereof was a Palatine, or Secular Prince, and his seal in form resembleth Royalty in the roundness thereof and is not oval, the badge of plain Episcopacy." CONTENTS . -

Chichester Diocesan Intercessions: July–September 2020

Chichester Diocesan Intercessions: J u l y – September 2020 JULY 10 Northern Indiana (The Episcopal Church) The Rt Revd Douglas 1 Sparks North Eastern Caribbean & Aruba (West Indies) The Rt Revd L. Bangor (Wales) The Rt Revd Andrew John Errol Brooks HIGH HURSTWOOD: Mark Ashworth, PinC; Joyce Bowden, Rdr; Attooch (South Sudan) The Rt Revd Moses Anur Ayom HIGH HURSTWOOD CEP SCHOOL: Jane Cook, HT; Sarah Haydon, RURAL DEANERY OF UCKFIELD: Paddy MacBain, RD; Chr Brian Porter, DLC 11 Benedict, c550 2 Northern Luzon (Philippines) The Rt Revd Hilary Ayban Pasikan North Karamoja (Uganda) The Rt Revd James Nasak Banks & Torres (Melanesia) The Rt Revd Alfred Patterson Worek Auckland (Aotearoa NZ & Polynesia) The Rt Revd Ross Bay Kagera (Tanzania) The Rt Revd Darlington Bendankeha Magwi (South Sudan) The Rt Revd Ogeno Charles Opoka MARESFIELD : Ben Sear, R; Pauline Ingram, Assoc.V; BUXTED and HADLOW DOWN: John Barker, I; John Thorpe, Rdr BONNERS CEP SCHOOL: Ewa Wilson, Head of School ST MARK’S CEP (Buxted & Hadlow Down) SCHOOL: Hayley NUTLEY: Ben Sear, I; Pauline Ingram, Assoc.V; Simpson, Head of School; Claire Rivers & Annette Stow, HTs; NUTLEY CEP SCHOOL: Elizabeth Peasgood, HT; Vicky Richards, Chr 3 St Thomas North Kigezi (Uganda) The Rt Revd Benon Magezi 12 TRINITY 5 Aweil (South Sudan) The Rt Revd Abraham Yel Nhial Pray for the Anglican Church of Papua New Guinea CHAILEY: Vacant, PinC; The Most Revd Allan Migi - Archbishop of Papua New Guinea ST PETERS CEP SCHOOL: Vacant, HT; Penny Gaunt, Chr PRAY for the Governance Team: Anna Quick; Anne-Marie -

The Missionary Reality of the Early Church and the Theology of the First Theologians

The Theology of the New Testament as Missionary Theology: The Missionary Reality of the Early Church and the Theology of the First Theologians Eckhard J. Schnabel Trinity Evangelical Divinity School Society of New Testament Studies, Halle, August 2-6, 2005 What we today call “theology,” the early Christians regarded as the proclamation of God’s saving acts that leads Jews and Gentiles to faith in Jesus the Messiah and Savior, that strengthens the faith of the followers of Jesus and that reinforces the relevance of the word of God in their everyday lives. The leading men and women of the early church were missionaries and evangelists: Peter in Jerusalem, in Samaria, in the cities of the coastal plain, in northern Anatolia and in Rome; Stephen and Philip in Jerusalem, in Samaria and in the cities of the coastal plain; Barnabas in Antioch and in Cyprus; Paul in Nabatea, in Syria, in Cilicia, in Galatia, in Asia, in Macedonia, in Achaia, in Illyria, in Rome and in Spain; Priscilla in Corinth, in Ephesus and in Rome; Timothy in Macedonia, in Achaia and in Ephesus; Phoebe in Corinth and in Rome; Apollos in Achaia, in Ephesus and on Crete; Thomas prob- ably in India, Matthew probably in Pontus, perhaps in Ethiopia, possibly in Syria; John Mark in Antioch, in Cyprus and in Rome; Luke in Antioch and in Macedonia; John in Jerusalem, in Samaria and in Ephesus. More names could be mentioned. You probably noticed that this list of names included all authors of the books of the New Testaments, with the exception of James, Jude and the unknown author of the Letter to the Hebrews. -

Anglicanism and the British Empire, 1829-1910

Edinburgh Research Explorer Anglicanism and the British Empire, 1829-1910 Citation for published version: Brown, S 2017, Anglicanism and the British Empire, 1829-1910. in R Strong (ed.), The Oxford History of Anglicanism: Partisan Anglicanism and its Global Expansion, 1829-c.1914 . vol. III, Oxford History of Anglicanism, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 45-68. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The Oxford History of Anglicanism Publisher Rights Statement: Brown, S. (2017). Anglicanism and the British Empire, 1829-1910. In R. Strong (Ed.), The Oxford History of Anglicanism: Partisan Anglicanism and its Global Expansion, 1829-c.1914 . (Vol. III, pp. 45-68). (Oxford History of Anglicanism). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Anglicanism in the British Empire, 1829-1910 Stewart J Brown In 1849, Daniel Wilson, the Evangelical Anglican bishop of Calcutta and metropolitan of India, published a Charge to his clergy. -

Commentary-On-Johns-Gospel-V1-Of

148 ANALYSIS OF THE l!'OURTH GOSPEL. [BOOK Il writings ascribe to the person of Christ in relation to the human soul absolutely the same central position as the Old Testament ascribes to God. For whom were absolute confi dence and love reserved by Moses and the prophets ? Jesus claims them for Himself in the Synoptics, and that in the name of our eternal salvation. Would Jewish Monotheism, so strict and so jealous of God's rights, have permitted Jesus to take such a position, had He not had the distinct conscious ness that in the background of His human existence there was a divine personality? He cannot as a faithful Jew desire to be to us what He asks to be in the Synoptics, unless He is what He claims to be in J ohn.1 This general conclusion is reinforced by a large number of particular facts in the same writings. We have just seen how, in Luke, He who comes after the forerunner is called in the preceding words the Lord their God. In Mark, the person of the Son is placed above even the most exalted creatures: "But of that day knoweth no man, no, not the angels which are in heaven, neither the Son [ during the time of His humilia tion], but the Father" (xiii. 32). In Matthew, the Son is. placed between the Father and the Holy Spirit, the breath of God : " Baptize all nations in the name of the Father, of the· Son, and of the Holy Ghost" (xxviii. 19 ). In the parable of the husbandmen, Jesus represents Himself, in contrast to the servants sent before Him, as the son and heir of the master of the vineyard (Matt. -

Resurrection: Faith Or Fact? Miracle Not Required?

209 Resurrection: Faith or Fact? Miracle Not Required? Peter S. Williams Assistant Professor in Communication and Worldviews NLA University College, Norway [email protected] I was privileged to have the opportunity material, he cannot justify his assertion to contribute two chapters to Resur rec tion: that the Gospels contain both types of Faith or Fact? (Pitchstone, 2019). One of material (for example, Carl holds that the these chapters reviewed the written resur- crucifixion is historical but the empty rection debate therein between atheist tomb isn’t). Contra Carl, I maintain that Carl Stecher (Professor Emeritus of Eng - the historical ‘criteria of authenticity’3 lish at Salem State University) and Chris- provide us with principled ways of ‘deter- tian Craig L. Blomberg (Distinguished mining what [in the resurrection narrati- Professor of the New Testament at Den- ves] is actually historical.’4 ver Seminary in Colorado).1 While I had In ‘Miracle Not Required’, Carl makes a couple of critical comments relating to an apparent mea culpa that quickly turns Professor Blomberg’s chapters, I focused into a red herring: my attention on Professor Stecher’s con- Peter’s challenge is justified; at the tribution to the debate, grouping my very least my point needs clarifica- observations under the headings listed in tion. My statement reflects a posi- the title of my review chapter: ‘Evidence, tion of skepticism and the rejection Explanation and Expectation’ (‘EEE’). In of Christian biblical literalism and infallibility . This is, after all, a his closing essay, ‘Miracle Not Required’, pivotal issue in any consideration Carl responded to ‘EEE’. -

Who Was Jesus of Nazareth?

WHO WAS JESUS OF NAZARETH? Craig L. Blomberg1 Jesus of Nazareth has been the most influential person to walk this earth in human history. To this day, more than two billion people worldwide claim to be his followers, more than the number of adherents to any other religion or worldview. Christianity is responsible for a disproportionately large number of the humanitarian advances in the history of civilization—in education, medicine, law, the fine arts, working for human rights, and even in the natural sciences (based on the belief that God designed the universe in an orderly fashion and left clues for people to learn about it).2 But just who was this individual and how can we glean reliable information about him? A recent work on popular images of Jesus in America alone identifies eight quite different portraits: “enlightened sage,” “sweet savior,” “manly redeemer,” “superstar,” “Mormon elder brother,” “black Moses,” “rabbi,” and “Oriental Christ.”3 Because these depictions contradict each other at various points, they cannot all be equally accurate. Historians must return to the ancient evidence for Jesus and assess its merits. This evidence falls into three main categories: non-Christian, historic Christian, and syncretistic (a hybrid of Christian and non-Christian perspectives). Non-Christian Evidence for Jesus An inordinate number of websites and blogs make the wholly unjustified claim that Jesus never existed. Biblical scholars and historians who have investigated this issue in detail are virtually unanimous today in rejecting this view, regardless of their theological or ideological perspectives. A dozen or more references to Jesus appear in non-Christian Jewish, Greek, and Roman sources in the earliest centuries of the Common Era (i.e., approximately from the birth of Jesus onward, as Christianity and Judaism began to overlap chronologically). -

Historical Criticism and the Evangelical Grant R

11-Osborne_JETS 42.2 Page 193 Friday, May 21, 1999 12:58 PM JETS 42/2 (June 1999) 193–210 HISTORICAL CRITICISM AND THE EVANGELICAL GRANT R. OSBORNE* Since the inception of historical criticism (hereafter HC) in the post- Enlightenment period of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, con- servatives and evangelicals have wrestled with their relationship to this discipline. Due to its origins in rationalism and anti-supernaturalism, it has been a stormy relationship. In the nineteenth century, the Cambridge trio Lightfoot, Westcott and Hort opposed the liberal movements of rationalism and tendency criticism (F. C. Baur) with a level of scholarship more than equal to their opponents, and in Germany Theodor Zahn and Adolf Schlatter opposed the incursion of HC. In America scholars like Charles Hodge and Benjamin War˜eld in theology and J. Gresham Machen and O. T. Allis in biblical studies fought valiantly for a high view of Scripture along with a critical awareness of issues. However, in none of these conservative scholars do we ˜nd a wholesale rejection of critical tools. From the 1920s to the 1940s little interaction occurred as fundamental- ism turned its back on dialogue with higher critics, believing that to interact was to be tainted by contact with the methods. It was then that wholesale rejection of critical methodology became standard in fundamentalist schol- arship. However, in the late 1940s the rise of evangelicalism (including the birth of ETS!) renewed that debate, and scholars like George Ladd and Leon Morris once more began to champion a high view of Scripture within the halls of academia.