Anglicanism and the British Empire, 1829-1910

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empty Tomb

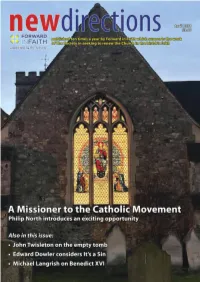

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900 Hancock, Christopher David How to cite: Hancock, Christopher David (1984) The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7473/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 VOLUME II 'THE PRIESTHOOD OF CHRIST IN ANGLICAN DOCTRINE AND DEVOTION: 1827 -1900' BY CHRISTOPHER DAVID HANCOCK The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Durham, Department of Theology, 1984 17. JUL. 1985 CONTENTS VOLUME. II NOTES PREFACE 1 INTRODUCTION 4 CHAPTER I 26 CHAPTER II 46 CHAPTER III 63 CHAPTER IV 76 CHAPTER V 91 CHAPTER VI 104 CHAPTER VII 122 CHAPTER VIII 137 ABBREVIATIONS 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 1 NOTES PREFACE 1 Cf. -

Oxford Book Fair List 2014

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD OXFORD BOOK FAIR LIST including NEW ACQUISITIONS ● APRIL 2014 Main Hall, Oxford Brookes University (Headington Hill Campus) Gipsy Lane, Oxford OX3 0BP Stand 87 Saturday 26th April 12 noon – 6pm - & - Sunday 27th April 10am – 4pm A MEMOIR OF JOHN ADAM, PRESENTED TO THE FORMER PRIME MINISTER LORD GRENVILLE BY WILLIAM ADAM 1. [ADAM, William (editor).] Description and Representation of the Mural Monument, Erected in the Cathedral of Calcutta, by General Subscription, to the Memory of John Adam, Designed and Executed by Richard Westmacott, R.A. [?Edinburgh, ?William Adam, circa 1830]. 4to (262 x 203mm), pp. [4 (blank ll.)], [1]-2 (‘Address of the British Inhabitants of Calcutta, to John Adam, on his Embarking for England in March 1825’), [2 (contents, verso blank)], [2 (blank l.)], [2 (title, verso blank)], [1]-2 (‘Description of the Monument’), [2 (‘Inscription on the Base of the Tomb’, verso blank)], [2 (‘Translation of Claudian’)], [1 (‘Extract of a Letter from … Reginald Heber … to … Charles Williams Wynn’)], [2 (‘Extract from a Sermon of Bishop Heber, Preached at Calcutta on Christmas Day, 1825’)], [1 (blank)]; mounted engraved plate on india by J. Horsburgh after Westmacott, retaining tissue guard; some light spotting, a little heavier on plate; contemporary straight-grained [?Scottish] black morocco [?for Adam for presentation], endpapers watermarked 1829, boards with broad borders of palmette and flower-and-thistle rolls, upper board lettered in blind ‘Monument to John Adam Erected at Calcutta 1827’, turn-ins roll-tooled in blind, mustard-yellow endpapers, all edges gilt; slightly rubbed and scuffed, otherwise very good; provenance: William Wyndham Grenville, Baron Grenville, 3 March 1830 (1759-1834, autograph presentation inscription from William Adam on preliminary blank and tipped-in autograph letter signed from Adam to Grenville, Edinburgh, 6 March 1830, 3pp on a bifolium, addressed on final page). -

Life and Letters of Brooke Foss Westcott Vol. I

ST. mars couKE LIFE AND LETTERS OF BROOKE FOSS WESTCOTT Life and Letters of Foss Westcott Brooke / D.D., D.C.L. Sometime Bishop of Durham BY HIS SON ARTHUR WESTCOTT WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I 117252 ILonfcon MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1903 Ail rights reserved "To make of life one harmonious whole, to realise the invisible, to anticipate the transfiguring majesty of the Divine Presence, is all that is worth living for." B. F. \V. FRATRI NATU MAXIMO DOMUS NOSTRAE DUCI ET SIGNIFERO PATERNI NOMINIS IMPRIMIS STUDIOSO ET AD IPSIUS MEMORIAM SI OTIUM SUFFECISSET PER LITTERAS CELEBRANDAM PRAETER OMNES IDONEO HOC OPUSCULUM EIUS HORTATU SUSCEPTUM CONSILIIS AUCTUM ATQUE ADIUTUM D. D. D. FRATER NATU SECUNDUS. A. S., MCMIII. FRATKI NATU MAXIMO* 11ace tibi in re. ai<-o magni monnmcnta Parent is Maioi'i natu, frater, amo re pari. Si<jui'i inest dignnni, lactabere ; siquid ineptnm, Non milii tn censor sed, scio, [rater eris. Scis boif qnam duri fnerit res ilia laboris, Qnae melius per te suscipienda fiiit. 1 Tie diex, In nobis rcnoi'ali iwiinis /icres, Agtniw's ct nostri signifer unus eras. Scribcndo scd enim spatiiim, tibi sorte ncgatum, Iniporlnna minus fata dedcre mihi : Rt levin.: TISUDI cst infabrius arnia tulisse (Juain Patre pro tanto nil voluisse pati. lament: opus exaction cst quod, te sitadcnte, siibivi . Aecipc : indicia stctque cadatqne tno. Lcctorurn hand dnbia cst, reor, indulgentia. ; nalo Quodfrater frat ri tu dabis, ilia dabit. Xcc pctinins landcs : magnani depingerc vitani Ingcnio fatcor grandins ess.: nieo. Hoc erat in votis, nt, nos quod atnavinms, Hind Serns in cxtcrnis continnaret amor. -

Download 1 File

GHT tie 17, United States Code) r reproductions of copyrighted Ttain conditions. In addition, the works by means of various ents, and proclamations. iw, libraries and archives are reproduction. One of these 3r reproduction is not to be "used :holarship, or research." If a user opy or reproduction for purposes able for copyright infringement. to accept a copying order if, in its involve violation of copyright law. CTbc Minivers U^ of Cbicatjo Hibrcmes LIGHTFOOT OF DURHAM LONDON Cambridge University Press FETTER LANE NEW YORK TORONTO BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS Macmillan TOKYO Maruzen Company Ltd All rights reserved Phot. Russell BISHOP LIGHTFOOT IN 1879 LIGHTFOOT OF DURHAM Memories and Appreciations Collected and Edited by GEORGE R. D.D. EDEN,M Fellow Pembroke Honorary of College, Cambridge formerly Bishop of Wakefield and F. C. MACDONALD, M.A., O.B.E. Honorary Canon of Durham Cathedral Rector of Ptirleigb CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1933 First edition, September 1932 Reprinted December 1932 February PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN 1037999 IN PIAM MEMORIAM PATRIS IN DEO HONORATISSIMI AMANTISSIMI DESIDERATISSIMI SCHEDULAS HAS QUALESCUNQUE ANNOS POST QUADRAGINTA FILII QUOS VOCITABAT DOMUS SUAE IMPAR TRIBUTUM DD BISHOP LIGHTFOOT S BOOKPLATE This shews the Bishop's own coat of arms impaled^ with those of the See, and the Mitre set in a Coronet, indicating the Palatinate dignity of Durham. Though the Bookplate is not the Episcopal seal its shape recalls the following extract from Fuller's Church 5 : ense History (iv. 103) 'Dunelmia sola, judicat et stola. "The Bishop whereof was a Palatine, or Secular Prince, and his seal in form resembleth Royalty in the roundness thereof and is not oval, the badge of plain Episcopacy." CONTENTS . -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Symeon Issue 9

SYMEON Issue Nine The magazine for alumni. Department of History, Durham University. 2019 02 SYMEON | Issue nine 03 When I was tasked with the selection of a theme for this year’s Symeon, the idea of connections seemed an obvious, and pertinent, choice. The current political climate has raised questions about the value of connections and collaboration versus independence; at the same time, the History Department’s collaborative activities have demonstrated how enriching academic partnerships can be. The report of the Durham-Münster Conference shows how students and staff from both universities embraced the chance not only to share their research, but for cultural exchange. The PKU-Tsinghua-Durham Colloquium offered similar opportunities; this event inspired Kimberley Foy and Honor Webb’s piece, ‘Seamless Connections’. More evidence of the Department’s activities can be found in Prof Sarah Davies round-up of this year’s ‘Department News’. Another focus of Issue 9 is the role today. Local war memorials are his childhood. Both his father, and his that historical research plays beyond another way of connecting people in mother, Mavis - the only woman on the university environment. Public County Durham to their past. Beth her course at King’s College, Durham engagement is becoming increasingly Brewer questions the involvement - instilled in him the importance important, and you can read about of women in the creation of these of knowledge. Family history adds the way in which two university staff, monuments: her article, ‘Primary another layer to social history, giving Dr Charlie Rozier and Prof Giles Mourners’ highlights how, though individuals a way to feel connected Gasper, have delivered their research women were the primary mourners to a history that is at once shared to a wider audience, through exciting, of First World War in the county, and personal. -

A Victorian Architectural Controversy

A Victorian Architectural Controversy: Who Was the Real Architect of the Houses of Parliament? A Victorian Architectural Controversy: Who Was the Real Architect of the Houses of Parliament? Edited by Ariyuki Kondo Assisted by Yih-Shin Lee A Victorian Architectural Controversy: Who Was the Real Architect of the Houses of Parliament? Edited by Ariyuki Kondo This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Ariyuki Kondo and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3944-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3944-0 To our families in Tokyo and Taipei in gratitude TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix Preface ........................................................................................................ xi Acknowledgements ................................................................................... xv PART I INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER ............................................................................ 3 A Victorian Architectural Controversy: Who Was the Real Architect of the Houses of Parliament? -

In the Desert Places of the Wilderness : the Frontier Thesis and The

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — “In the desert places of the wilderness”: The Frontier Thesis and the Anglican Church in the Eastern Townships, 1799–1831 J. I. LITTLE* The Church of England was better able to meet the challenges of the settlement fron- tier in British North America than historians have sometimes acknowledged. Even in Quebec’s Eastern Townships, a region largely populated by American settlers, the British-backed religion of order tended to dominate the religion of dissent during the early settlement period. It was thus well entrenched by the 1830s and 1840s, when American missionary societies and revivalist sects began to take a greater interest in the region. Not only did the Anglican Church have substantial material advantages over its competitors, but the Anglican hierarchy was willing to adapt, within limits, to local conditions. This case study of the two neighbouring parishes in St. Armand, near the Vermont border, also shows that each British-born Anglican missionary responded to the challenges posed by an alien cultural environment in a somewhat different way. L’Église anglicane était plus apte à relever les défis du peuplement de l’Amérique du Nord britannique que les historiens ne l’ont parfois reconnu. Même dans les Cantons de l’Est, au Québec, une région largement peuplée par des colons améri- cains, la religion de l’ordre, qui jouissait du soutien britannique, avait tendance à dominer la religion de la dissension aux débuts du peuplement. Elle était donc bien enracinée quand, durant les années 1830 et 1840, les sociétés missionnaires améri- caines et les sectes revivalistes commencèrent à s’intéresser davantage à la région. -

History of the Church Missionary Society", by E

Durham E-Theses The voluntary principle in education: the contribution to English education made by the Clapham sect and its allies and the continuance of evangelical endeavour by Lord Shaftesbury Wright, W. H. How to cite: Wright, W. H. (1964) The voluntary principle in education: the contribution to English education made by the Clapham sect and its allies and the continuance of evangelical endeavour by Lord Shaftesbury, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9922/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 THE VOLUNTARY PRINCIPLE IN EDUCATION: THE CONTRIBUTION TO ENGLISH EDUCATION MADE BY THE CLAPHAil SECT AND ITS ALLIES AM) THE CONTINUAi^^CE OP EVANGELICAL EI-JDEAVOUR BY LORD SHAFTESBURY. A thesis for the degree of MoEd., by H. T7right, B.A. Table of Contents Chapter 1 The Evangelical Revival -

Bishop Bruce J. A. Myers OGS Officially Takes Office As the 13Th

JUNE 2017 A SECTION OF THE ANGLICAN JOURNAL ᑯᐸᒄ ᑲᑭᔭᓴᐤ ᐊᔭᒥᐊᐅᓂᒡ • ANGLICAN DIOCESE OF QUEBEC • DIOCÈSE ANGLICAN DE QUÉBEC Waiting outside for the service to begin, the Bishop does a little meet, greet with some visiting students. Photo: ©Daniel Abel/photographe-Québec Bishop Bruce J. A. Myers OGS officially takes office as the Photo: ©Daniel Abel/photographe-Québec 13th Lord Bishop of Quebec. On Saturday April them and explain what was bruce-myers-lors-de-son- ist remarking that now he is 22, 2017 Bruce Myers OGS going on and to invite them intronisation spreading the “good news” was officially welcomed and to come closer to witness to seated as the thirteenth Lord his knocking on the door. Following Commu- David Weiser of Beth Bishop of Quebec. nion but before the Blessing Israel Ohev Sholom brought Upon hearing the there were official greetings. thoughts and greetings from Over three hundred knocks the wardens an- The Primate of the Anglican the local Jewish community. people attended the event nounced to the assembled Church of Canada, the Most in the Cathedral of the Holy congregation “Sisters and Rev. Fred Hiltz, and the Met- Boufeldja Benabdal- Trinity. They came from brothers of the diocese of ropolitan of Canada, the Most lah, the cofounder of the across the diocese as well as Quebec, our new bishop has Rev. Percy Coffin, brought Centre culturel Islamique de from the rest of Canada and arrived at his cathedral to both official and personal Quebec, thanked the Bishop the United States. claim his place in our midst. heartfelt greetings of support for his support after the at- Let the doors be opened and for Bishop Bruce as he begins tack in January on the Grande Bishop Drainville let us rise to greet him” his new role. -

Instructing Them In'the Things of God': the Response of the Bishop And

Faculty of Education and Social Work Instructing them in ‘the things of God’: The response of the Bishop and the Synod of the Church of England in the Diocese of Sydney to the Public Instruction Act 1880 (NSW) regarding religious education for its children and young people, 1880-1889 Riley Noel Warren AM BEd (Canberra) A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education (Research) 2014 Faculty of Education and Social Work Office of Doctoral Studies AUTHOR’S DECLARATION This is to certify that: I. this thesis comprises only my original work towards the Master of Education (Research) Degree II. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used III. the thesis does not exceed the word length for this degree. IV. no part of this work has been used for the award of another degree. V. this thesis meets the University of Sydney’s Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) requirements for the conduct of research. Signature: …………………………………………………………………………………………… Name: Riley Noel WARREN Date: …………………………………………………………………………………………… ii Preface and Acknowledgements Undertaking this research has allowed me to combine three of my interests; history, education and the Anglican Diocese of Sydney. History was the major concentration of my first degree. I retired in 2008, after twenty years, from the Headmastership of Macarthur Anglican School, Cobbitty, NSW. I have served for a similar time on the Synod of Sydney and its Standing Committee as well as some time on Provincial and General Synods. I have an abiding interest in the affairs of the Diocese of Sydney generally and particularly in educational matters.