Putting Alumni on the Path to Lifelong Civic Engagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Year's Whole School Whole Child Model on Partner Schools

ANALYSIS OF THE IMPACTS OF CITY YEAR’S WHOLE SCHOOL WHOLE CHILD MODEL ON PARTNER SCHOOLS’ PERFORMANCE June 4, 2015 Julie Meredith Leslie M. Anderson POLICY STUDIES ASSOCIATES, INC. Commissioned by City Year Analysis of the Impacts of City Year’s Whole School Whole Child Model on Partner Schools’ Performance City Year is an education-focused organization founded in 1988 dedicated to helping students and schools succeed. City Year partners with public schools in 26 urban, high-poverty communities across the United States and through interna- tional affiliates in the United Kingdom and Johannesburg, South Africa. Diverse teams of City Year AmeriCorps mem- bers provide student, classroom, and schoolwide support to help students stay in school and on track to graduate from high school, ready for college and career success. A proud member of the AmeriCorps national service network, City Year is made possible by support from the Corporation for National and Community Service, school district partnerships, and private philanthropy from corporations, foundations, and individuals. City Year AmeriCorps members are 17- to 24-year-olds who commit to one year of full-time service in elementary, middle, or high schools. Working on 7- to 18-person, school-based teams, City Year AmeriCorps members (or corps members) de- liver City Year’s Whole School Whole Child (WSWC) model, which is a portfolio of services delivered in and outside of the classroom. Specifically, the model is intended to serve all students in a school, providing additional support to students at risk of dropping out based on their attendance, behavior, and course performance. -

For Student Success

TRANSFORMING School Environments OUR VISION For Student Success Weaving SKILLS ROPES Relationships 2018 Annual Report Practices to Help All Students Our Vision for Student Success City Year has always been about nurturing and developing young people, from the talented students we serve to our dedicated AmeriCorps members. We put this commitment to work through service in schools across the country. Every day, our AmeriCorps members help students to develop the skills and mindsets needed to thrive in school and in life, while they themselves acquire valuable professional experience that prepares them to be leaders in their careers and communities. We believe that all students can succeed. Supporting the success of our students goes far beyond just making sure they know how to add fractions or write a persuasive essay—students also need to know how to work in teams, how to problem solve and how to work toward a goal. City Year AmeriCorps members model these behaviors and mindsets for students while partnering with teachers and schools to create supportive learning environments where students feel a sense of belonging and agency as they develop the social, emotional and academic skills that will help them succeed in and out of school. When our children succeed, we all benefit. From Our Leadership Table of Contents At City Year, we are committed to partnering Our 2018 Annual Report tells the story of how 2 What We Do 25 Campaign Feature: with teachers, parents, schools and school City Year AmeriCorps members help students 4 How Students Learn Jeannie & Jonathan Lavine districts, and communities to ensure that all build a wide range of academic and social- 26 National Corporate Partners children have access to a quality education that emotional skills to help them succeed in school 6 Alumni Profile: Andrea Encarnacao Martin 28 enables them to reach their potential, develop and beyond. -

Ohio Service Locations

Ohio | Service Location Report 2020 YEAR IN REVIEW AmeriCorps City Service Locations Project Name Program Type Completed* Current Sponsor Organization Participants Participants Akron Akron Better Block Foundation AmeriCorps VISTA 2 - Better Block Foundation Akron Akron - Summit County Dep't of The Ohio Opportunity Youth Initiative AmeriCorps VISTA - 1 Job & Family Services The Ohio State University - Kirwan Institute Akron Akron Circles Think Tank AmeriCorps VISTA 1 - Think Tank Akron Akron Metropolitan Housing Serve New York AmeriCorps VISTA - 1 Authority The Service Collaborative of WNY, Inc. Akron Akron-Canton Regioanl ShareCorps One AmeriCorps VISTA 2 3 Foodbank Ohio Association of Foodbanks Akron Asian Services in Action, Inc. Ohio CDC Association/AFIA AmeriCorps VISTA 1 - Ohio CDC Association Akron Bright Star Books Family & Community Services Intermediary AmeriCorps VISTA 1 - Project Family & Community Services Inc. Akron County of Summit ADM Board Addressing Ohio's Opioid Epidemic AmeriCorps VISTA 1 1 Ohio Association of County Behavioral Health Authorities Fdn Akron Good Samaritan Hunger Center ShareCorps One AmeriCorps VISTA 1 1 Ohio Association of Foodbanks Akron Kenmore Neighborhood Ohio CDC Association/AFIA AmeriCorps VISTA - 1 Alliance Ohio CDC Association Akron Summit Soil & Water NOWCorps AmeriCorps State - 1 Conservation District Tinker's Creek Watershed Partners, Inc. Akron The Well Community Ohio CDC Association/AFIA AmeriCorps VISTA 1 1 Development Corporation Ohio CDC Association Akron United Way Summit County United -

Volunteer Impact Report

volunteer impact report city year boston 2018-2019 service in boston 4 building partnerships 10 volunteer impact 13 community 16 mindfulness 17 before/after 18 get involved 19 Service is a priority I love Boston, and I love getting to know the people and communities that make our neighborhoods thrive. So, I am pleased to present City Year’s 2018-2019 Volunteer Impact Report! City Year has been building connections through service in Boston for over 30 years. In that time, we’ve created lasting partnerships founded on the idea that service groups can and do make a difference. We work closely with Boston Public Schools to support the future of our communities: our students. Teams of AmeriCorps members serve in schools, improving students’ attendance, motivation to learn, and performance in English and math. We also recognize that many factors contribute to students’ success—including a supportive, bright learning environment. So, each year, our AmeriCorps members engage thousands of volunteers in projects that contribute to the vibrancy of schools, hallways, and classrooms. We know that learning also takes place outside of schools, so we regularly engage in service projects that show students we are invested in their whole lives by serving in parks, community centers, and beyond. As you will read in this report, these projects are designed in consultation with students, teachers, and neighbors so that we can provide precisely the outcomes that will best benefit those we serve. We couldn’t complete these important service days without our amazing volunteers and partners, a group of committed citizens who want to send a strong message to the students of Boston that we are all in this together and that their success will be our success. -

ABOUT CITY YEAR What We Do and Why City Year Helps Students and Schools Succeed

ABOUT CITY YEAR What We Do and Why City Year helps students and schools succeed. Fueled by OUR INTENDED IMPACT national service, City Year partners with public schools City Year has the ability to add much-needed capacity in 28 urban, high-need communities across the U.S. and to urban schools and help meet the holistic needs of all through international affiliates in the U.K. and Johannesburg, students, ensuring that they achieve at high levels and are South Africa. Diverse teams of City Year AmeriCorps on track to graduate from high school. Research shows that members provide research-based student, classroom and when students start the 10th grade on time and on track, school-wide support to help students stay in school and on their chances for success in career, college and life increase track to graduate from high school, ready for college and exponentially—outcomes that benefit all of us. career success. City Year AmeriCorps members serve in schools full-time OUR BELIEF as tutors, mentors and role models, delivering integrated, All children deserve a high-quality education to become personalized academic and social-emotional supports prosperous and productive adults who are equipped with rooted in research to students who need them most. the skills and knowledge required for success in college, These interventions help students build the skills and career and life. mindsets required to succeed in the 21st century economy and society. THE CHALLENGE More than 10 million children live in neighborhoods of By 2023, City Year seeks to dramatically increase the concentrated poverty and are more than two times more number of students who arrive on track and on time to the likely to face adverse childhood experiences, including 10th grade to 80 percent in the schools we serve. -

INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY STRENGTHENING the 21ST CENTURY TALENT PIPELINE Through National Service in High-Need Schools Introduction

INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY STRENGTHENING THE 21ST CENTURY TALENT PIPELINE Through National Service in High-Need Schools Introduction Employers are demanding new skills and competencies for Employers and City Year AmeriCorps members themselves today’s rapidly diversifying workforce, including problem are increasingly aware of the benefits of City Year’s unique solving, collaboration, communication, adaptability and approach to leadership development, civic engagement and self-awareness.1, 2 Postsecondary attainment has become skill building. Companies, organizations and public school an important determinant of success in the 21st century. systems understand that a “city year” is a career accelerator, By 2025, 65% of all U.S. jobs3 will require postsecondary and they are eager to mentor, hire and promote our alumni, education and training. Based on current rates, the U.S. will now more than 27,500 strong. Likewise, corps members be short several million skilled workers to fill these jobs.4 attest to the valuable competencies they build while serving in urban schools as part of a dedicated, diverse team – from As expectations for educational and skill attainment “hard” skills such as data analysis and project management rise in the U.S., more than 10 million children living in to interpersonal skills in high demand by employers, neighborhoods of concentrated poverty are being left such as learning how to collaborate with people from 5 behind. Large groups of students, including low-income diverse backgrounds, problem solving and relationship -

City Year Mid-Year Americorps Member Pre-Interview Information Pre-Interview Information

City Year Mid-Year AmeriCorps Member Pre-Interview Information Pre-Interview Information CULTURE AND DIVERSITY City Year’s culture is based on the foundation of teamwork and diversity. We embrace diversity of every kind and see differences as strengths that help us meet our goals to get students to graduation. The communities we work in are incredibly diverse and the unique perspectives of our diverse teams of City Year AmeriCorps members enables us to provide the greatest impact for the students we serve. Having a team with different interests, work styles, backgrounds, and experiences helps us ensure there is someone that can connect with and get through to every single student. The City Year uniform is a symbol of our full-time commitment to service. By wearing the uniform, we identify ourselves as practicing idealists who are ready to lead. The uniform provides the children, youth and members of the community we work with a signal of reliability, idealism and inspiration. Professional appearance guidelines are intended to create minimal distractions for the children and youth we serve, to support AmeriCorps member safety and to foster professionalism of the AmeriCorps members. City Year guidelines are not meant to constrain AmeriCorps members’ individuality, but rather to present a unified and easily recognizable symbol of our commitment. City Year AmeriCorps members do not wear non-uniform scarves, bandanas, or buttons that would detract from the professional look of the uniform. As role models to children, City Year AmeriCorps members must conduct themselves as professionals and representatives of City Year. These standards include the following while in City Year uniform: . -

Innovative State Service COVID-19 Response Programs America's

Innovative State Service COVID-19 Response Programs America’s Service Commissions Innovative State Service COVID-19 Response Programs America’s Service Commissions About America’s Service Commissions America’s Service Commissions (ASC) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan association representing and promoting the 52 state service commissions across the United States and territories with the mission to lead and elevate the state service network. State service commissions are governor-appointed public agencies or nonprofit organizations made up of more than 1,000 commissioners, private citizens leading the nation’s service movement and administering 80 percent of the federal AmeriCorps funds to address pressing community needs. Learn more at statecommissions.org. Publication Coordinators Lindsey Stevens, America’s Service Commissions Emily Steinberg, America’s Service Commissions © 2021 America’s Service Commissions. All rights reserved. Innovative State Service COVID-19 Response Programs America’s Service Commissions TABLE OF CONTENTS ALABAMA ..................................................................................................................... AMERICORPS INSTRUCTIONAL SUPPORT TEAM………………………………………………………….... SELMA AMERICORPS ............................................................................................................................. ALASKA ........................................................................................................................ SITKA AMERICORPS............................................................................................................................ -

Post and Email for Open Positions

AmeriCorps Member (Student Success Coach), City Year, Inc. (Full-Time Position starting in mid-July/early August to late May/early June) Baton Rouge, LA Milwaukee, WI Boston, MA Manchester, NH Buffalo, NY Memphis, TN Chicago, IL New Orleans, LA Cleveland, OH New York City. NY Columbia, SC Orlando, FL Columbus, OH Philadelphia, PA Dallas, TX Providence, RI Denver, CO Sacramento, CA Detroit, MI San Antonio, TX Jacksonville, FL San José/Silicon Valley, CA Kansas City, MO Seattle/King County, WA Little Rock, AR Tulsa, OK Los Angeles, CA Washington, DC Miami, FL City Year AmeriCorps Member: How will you build your legacy? We seek to build teams of diverse, resilient, and highly motivated young adults to support students and communities through one year of full-time paid service. As tutors, focusing on English and Math strategies with 3rd – 9th graders, we facilitate small group academic sessions with students. As mentors, we coach and guide students through their academic and social challenges. As after-school providers, we take lead on clubs, sports, and events to extend learning and build near-peer relationships with students as individuals. In doing so, we’re helping to increase graduation rates across the country and change the lives of the students we serve. Not only are our young adult leaders leaving a legacy of service and impact in their communities, they are then continuing to apply their newly developed and fine-tuned skill sets in the fields of education, law, public policy, or whatever other field they choose. A year of service is more than just a year of volunteerism and helping others, it's an investment and commitment to the betterment of society as a whole. -

State Service Location Year in Review

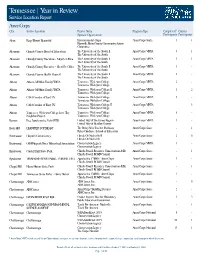

Tennessee | Year in Review Service Location Report AmeriCorps City Service Location Project Name Program Type Completed* Current Sponsor Organization Participants Participants Alcoa Keep Blount Beautiful Environmental Corps AmeriCorps State 1 1 Knoxville Knox County Community Action Committee Altamont Grundy County Board of Education The University of the South II AmeriCorps VISTA 3 1 The University of the South Altamont Grundy County Executive - Mayor's Office The University of the South II AmeriCorps VISTA 1 1 The University of the South Altamont Grundy County Executive - Sheriff's Office The University of the South II AmeriCorps VISTA 1 - The University of the South Altamont Grundy County Health Council The University of the South II AmeriCorps VISTA 2 - The University of the South Athens Athens-McMinn Family YMCA Tennessee Wesleyan College AmeriCorps VISTA 2 - Tennessee Wesleyan College Athens Athens-McMinn Family YMCA Tennessee Wesleyan College II AmeriCorps VISTA 1 2 Tennessee Wesleyan College Athens CASA Corridor of East TN Tennessee Wesleyan College AmeriCorps VISTA 3 - Tennessee Wesleyan College Athens CASA Corridor of East TN Tennessee Wesleyan College II AmeriCorps VISTA - 3 Tennessee Wesleyan College Athens Tennessee Wesleyan College Love Thy Tennessee Wesleyan College AmeriCorps VISTA 6 - Neighbor Project Tennessee Wesleyan College Benton Free Lunch in the Park (FLIP) United Way of the Ocoee Region AmeriCorps VISTA 1 - United Way of Bradley County Berry Hill LEAD PREP SOUTHEAST The Relay New Teacher Pathway AmeriCorps State -

Startup Director City Year Tulsa

Startup Director City Year Tulsa Job Summary The Startup Director serves as the primary leader, external champion, and internal manager of the Startup Team. The role of the Startup Director of City Year Tulsa is to establish a new site and build a strong foundation from which the site can become a sustainable and results-driven institution in the Tulsa community. The Startup Director holds responsibility for the site’s performance and success in meeting critical performance metrics in advance of the site’s full launch and will facilitate the transition to a fully-operational site. Reporting to a Regional Vice President at City Year Headquarters (HQ), the Startup Director will work closely with the New Site Development team to transition local stakeholder and championship relationship management. This role is a temporary position that will conclude once a permanent Executive Director has been hired and onboarded. Responsibilities Responsibilities Meet the Phase III New Site Development Guideposts for new site authorization: -Recruit, select, and admit the founding year corps, meeting quality, quantity, and inclusivity goals. -Lead a strategic school R.F.P. process and select partner schools for the 2013- 2014 academic year in partnership with HQ - Secure and prepare office space -Transition the Founding Committee to a strong local site board of at least 10 members -Onboard the Executive Director Launch a pilot of the Whole School Whole Child model in two schools and cultivate partnerships to help achieve successful model implementation With the support of Headquarters, onboard and train startup staff and senior corps members Effectively manage the $1.2 million Startup budget to within five percent of the expense budget Secure additional private sector commitments to achieve 95% of revenue budget required for the first year of full operations (80% will have been secured by the launch of the startup team). -

South Carolina 2005 - 2006

South Carolina 2005 - 2006 Meeting community needs in South Carolina. More than 75,000 people of all ages and backgrounds are helping to meet local needs, strengthen communities, and increase civic engagement through 116 national service projects across South Carolina. Serving with national and local nonprofits, schools, faith-based organizations and other groups, these citizens tutor and mentor children, coordinate after-school programs, build homes, conduct neighborhood patrols, restore the environment, respond to disasters, build nonprofit capacity and recruit and manage volunteers. This year, the Corporation for National and Community Service will commit more than $15,400,000 to support South Carolina communities through three national service initiatives: Senior Corps: More than 4,900 seniors in South Carolina contribute their time and talents in one of three Senior Corps programs. Foster Grandparents serve one-on-one as tutors and mentors to more than 2,600 young people who have special needs. Senior Companions help more than 460 homebound seniors and other adults maintain independence in their own homes. Retired and Senior Volunteer Program (RSVP) volunteers conduct safety patrols for local police departments, participate in environmental projects, tutor and mentor youth, respond to natural disasters, and provide other services through more than 580 groups across South Carolina. AmeriCorps: This year AmeriCorps will provide more than 850 individuals the opportunity to provide intensive, results-driven service to meet education, environmental, public safety and other pressing needs in communities across South Carolina. Roughly three-quarters of all AmeriCorps grant funding goes to the Governor-appointed South Carolina Commission for National & Community Service, which in turn awards grants to nonprofit groups to respond to local needs.