Incubation and Brood Rearing by a Wild Male Mountain Quail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 GEO V 1921 No 57 Animals Protection and Game

12 GEO. V.] Animals Protection and Game. [1921, No. 57. 465 New Zealand. ANALYSIS. Title. PART IV. 1. Sbort Title and commencement. AC<JLDlATIZATION DIsTRICTS AND BOOIIIITIlIIS. S. Interpretation. 21. Acolimatization distriots. 22. ~ration of existing acclimatization looie· PART I. 23. Registration of societies formed after com· AlOMALII l'BOTBOTION. mencement of tbis Aot. 3. Certain animals to be absolutely protected. 24. Registered societies to be bodies oorporate. 4. PartiaJ protection of animals. 26. Alterations of rules to be approved by tbe 5. As to animals ceasing to be absolutely pro Minister. tected. 26. Annual balance-sheet, &0., to be forwarded to 6. Sanotuaries for imported and native game. Minister of Finance. 27. Wbere default made in forwarding balanoe 7. Land may be taken for sanotuaries, &c. sheet. 28. Vesting of animals in sooieti~. 29. Societies to notify Minister of imported PART IL animals tumed at large. Governor-General GAME. may vest in societies property in suoh animals. 8. Imported game and native ga.me. 9. Open seasons for imported and native game. PART V. O1fence to take or kill ga.me.during olose GENERAL. season. 30. Restriotion on importation, liberation, or 10. Notification as to oonditions on whioh open keeping of animals. Master, owner, &o.~ season deolared. of ship to prevent noxious reptiles or in- 11. No game to be trapped. Use of metal- sects from being landed in New Zealand. patched or metal-oased bullets unlawful. I Offenee. 12. Use of heavy guns unlawful. 31. Minister may authorize catching or taking of 13. Use of cylinders. silencers, and live decoys animals for certain purposes. -

Checklist: Birds of Andrew Molera State Park, Big Sur, California

Checklist: Birds of Andrew Molera State Park, Big Sur, California [ ] Red-throated Loon [ ] Cinnamon Teal [ ] * American Avocet [ ] ** Thick-billed Murre [ ] Pacific Loon [ ] * Northern Shoveler [ ] Greater Yellowlegs [ ] B Pigeon Guillemot [ ] Common Loon [ ] * Northern Pintail [ ] * Lesser Yellowlegs [ ] ** Marbled Murrelet [ ] Pied-billed Grebe [ ] Green-winged Teal [ ] * Solitary Sandpiper [ ] * Xantus' Murrelet [ ] Horned Grebe [ ] * Redhead [ ] Willet [ ] * Craveri's Murrelet [ ] Red-necked Grebe [ ] * Ring-necked Duck [ ] Wandering Tattler [ ] * Ancient Murrelet [ ] Eared Grebe [ ] * Greater Scaup [ ] Spotted Sandpiper [ ] Cassin's Auklet [ ] Western Grebe [ ] * Lesser Scaup [ ] Whimbrel [ ] Rhinoceros Auklet [ ] Clark's Grebe [ ] * Harlequin Duck [ ] * Long-billed Curlew [ ] * Tufted Puffin [ ] * Laysan Albatross [ ] Surf Scoter [ ] Marbled Godwit [ ] ** Horned Puffin [ ] Black-footed Albatross [ ] * White-winged Scoter [ ] * Ruddy Turnstone [ ] I Rock Dove [ ] Northern Fulmar [ ] * Black Scoter [ ] Black Turnstone [ ] B Band-tailed Pigeon [ ] Pink-footed Shearwater [ ] Common Goldeneye [ ] Surfbird [ ] ** White-winged Dove [ ] * Flesh-footed Shearwater [ ] * Barrow's Goldeneye [ ] * Red Knot [ ] B Mourning Dove [ ] Buller's Shearwater [ ] * Hooded Merganser [ ] Sanderling [ ] ** Common Ground-Dove [ ] Sooty Shearwater [ ] B Common Merganser [ ] Western Sandpiper [ ] ** Black-billed Cuckoo [ ] Black-vented Shearwater [ ] Red-breasted Merganser [ ] Least Sandpiper [ ] ** Yellow-billed Cuckoo [ ] Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel [ ] * Ruddy -

Target Species Mapping for the Green Visions Plan

Target Species Habitat Mapping California Quail and Mountain Quail (Callipepla californica and Oreortyx pictus) Family: Phasianidae Order: Galliformes Class: Aves WHR #: B140 and B141 Distribution: California quail are found in southern Oregon, northern Nevada, California, and Baja California, and have been introduced in other states such as Hawaii, Washington, Idaho, Colorado, and Utah (Peterson 1961). In California, they are widespread but absent from the higher elevations of the Sierra Nevada, the Cascades, the White Mountains, and the Warner Mountains, and are replaced by the related Gambel’s quail (C. gambelii) in some desert regions (Peterson 1961, Small 1994). In southern California, they are found from the Coast Range south to the Mexican border, and occur as far east as the western fringes of the Mojave and Sonoran deserts, such as in the Antelope Valley (Garrett and Dunn 1981, Small 1994). California quail range from sea level to about 5000 ft (1524 meters; Stephenson and Calcarone 1999) Mountain quail are resident from northern Washington and northern Idaho, south through parts of Oregon, northwestern Nevada, California, and northern Baja California (Peterson 1961). In southern California, mountain quail are found in nearly all of the mountain ranges west of the deserts, including the southern Coast Ranges, from the Santa Lucia Mountains south through Santa Barbara and Ventura counties, and the Peninsular Ranges south to the Mexican border (Garrot and Dunn 1981, Small 1994). In the Transverse Ranges, a small population occurs in the western Santa Monica Mountains, and larger populations occur in the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains (Small 1994). Mountain quail are found at elevations from below 2000 ft (610 meters) to over 9000 ft (2743 meters; Stephenson and Calcarone 1999). -

Grant Report California Quail

Grant Report California Quail Translocation from Idaho to Texas California Quail: Translocation from Idaho to Texas Final Report September 2020 Prepared by: Kelly S. Reyna, Jeffrey G. Whitt, Sarah A. Currier, Shelby M. Perry, Garrett T. Rushing, Jordan T. Conley, Curt A. Vandenberg, and Erin L. Moser. The Quail Research Laboratory, College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, Texas A&M University Commerce 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF FIGURES AND TABLES ................................................................................ 3 BRIEF: ................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 7 RESEARCH GOALS .................................................................................................... 8 PREDATOR IMPACTS ON TRANSLOCATED QUAIL ........................................................... 8 PREDATOR AVOIDANCE BEHAVIOR OF TRANSLOCATED QUAIL ...................................... 8 IMPACTS OF TEXAS HEAT ON VALLEY QUAIL DEVELOPMENT ........................................... 9 DEVELOPMENTAL TRAJECTORY OF CALIFORNIA VALLEY QUAIL .................................... 10 TRANSLOCATION WEIGHT LOSS ................................................................................ 10 PROJECT DESIGN............................................................................................... 11 MATERIAL AND METHODS ................................................................................ -

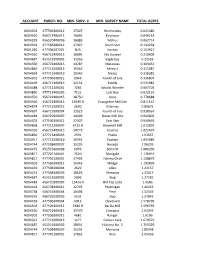

Account Parcel No. Min. Surv. # Min. Survey Name Total Acres

ACCOUNT PARCEL NO. MIN. SURV. # MIN. SURVEY NAME TOTAL ACRES N004302 477506300012 17307 Wednesday 0.041486 N004550 456722400015 16095 Keystone 0.046553 N004329 456520400006 16089 Walrus 0.062714 N004302 477506300012 17307 South Star 0.133258 R001186 477506207001 N/A Ironton 0.153927 N004550 456722400015 16095 Sky Scraper 0.219906 N004687 451519100002 11956 Eagle Eye 0.22526 N004550 456722400015 14787 Matanzas 0.303452 N004840 477713200013 19343 Selma 2 0.311987 N004924 477713300019 19343 Mezzo 0.328382 N004302 477506300012 6946 Fourth of July 0.336807 N004469 456717400015 12151 Estella 0.531982 N004488 477712100001 7265 Schultz Wonder 0.607702 N004830 477713400005 7121 Lost Boy 0.622125 N004550 456722400015 18750 Gore 0.778688 N004550 456722400015 12949 B Evangeline Mill Site 0.811167 N004874 477713300012 2690 Killarney 0.89675 N004697 456719100004 13523 Fourth of July 0.938567 N004484 456720300007 14499 Blazer Mill Site 0.944802 N004302 477506300012 17307 East Star 0.949663 N004868 477712200007 6712 B Brownell Mill 1.012899 N004550 456722400015 14773 Cosmos 1.021479 N004830 477713400005 2591 Puzzle 1.03637 N004917 477713300016 19335 Captain 1.055989 N004744 477508400007 15205 Nevada 1.06235 N004472 451519300008 6956 Bennett 1.086269 N004817 477701100001 7020 Marigold 1.126919 N004817 477701100001 17493 Yakima Chief 1.158879 N004302 477506300012 19343 Wedge 1.192899 N004459 477506300004 2629 Allen 1.22157 N004431 477508300005 18626 Primrose 1.33017 N004687 451519100002 5906 King 1.37281 N004484 456720300007 13424 A Hill Top Lode 1.4586 N004464 456728100012 12749 Ptarmigan 1.46463 N004738 456716300004 16494 Ymir 1.52425 N004335 456729200003 5532 Gap 1.57842 N004459 477506300004 6913 Cleveland 1.578799 N004302 477506300012 2386 B Barilla Mill 1.596539 N004550 456722400015 15370 Compass 1.61097 N004302 477506300012 4681 Ranger 1.6196 R006562 477713300013 1177 Carbon Lake 1.679579 N004687 451519100002 18031 Hultona No. -

Landbird Inventory for Devil's Postpile

Landbird Inventory for Devil’s Postpile National Monument Final Report Rodney B. Siegel and Robert L. Wilkerson with collaboration from Sacha K. Heath The Institute for Bird Populations P.O. Box 1346 Point Reyes Station, CA 94956-1346 April 7, 2004 Cooperative Agreement H9471011196 Table of Contents List of Tables................................................................................................................... iii List of Figures ................................................................................................................. iii Summary ..........................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgments.............................................................................................................v Introduction .......................................................................................................................1 Methods.............................................................................................................................2 Sampling strategy..................................................................................................2 Field methods........................................................................................................2 Crew training and testing ......................................................................................3 Data analysis .........................................................................................................3 -

Checklist of the Birds of Fresno and Madera Counties

CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF FRESNO AND MADERA COUNTIES SPECIES FRE MAD STATUS HABITAT Sp Su Fa Wi NOTES ANATIDAE: Ducks, Geese, and Swans FULVOUS WHISTLING-DUCK X X Ex Ma,Wa Former summer visitor; no records since 1992. GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE X X Ma,Wa,Ag R X R U Two summer records; both from Madera WTP. SNOW GOOSE X X Ma,Wa,Ag R R U ROSS'S GOOSE X X Ma,Wa,Ag R R U BRANT X Va Wa X X X Three records, all from Fresno County. CACKLING GOOSE X X "MINIMA" Ma,Wa,Ag R R U "ALEUTIAN" Ma,Wa,Ag R R R CANADA GOOSE X X Br Resident "WESTERN" Br Ma,Wa,Ag FC FC FC FC Migratory "WESTERN" Ma,Wa,Ag U U FC "LESSER" Ma,Wa,Ag R R R TUNDRA SWAN X X Ma,Wa R WOOD DUCK X X Br Ma,Wa U U U U GADWALL X X Br Ma,Wa FC FC FC C EURASIAN WIGEON X X Va Ma,Wa X X X AMERICAN WIGEON X X Ma,Wa U X U C MALLARD X X Br Ma,Wa FC FC FC C BLUE-WINGED TEAL X X Br Ma,Wa R X R R CINNAMON TEAL X X Br Ma,Wa U U U F NORTHERN SHOVELER X X Ma,Wa FC R FC C NORTHERN PINTAIL X X Ma,Wa U X U FC One historical breeding record. GARGANEY X Va Ma,Wa X Two records of hunter-shot birds. GREEN-WINGED TEAL X X "AMERICAN" Ma,Wa U X U FC "EURASIAN" Va Ma,Wa X Two records. -

Sonoma County Bird List

Sonoma County Bird List Benjamin D. Parmeter and Alan N. Wight October 23, 2018 This is a list of all of the bird species recorded in Sonoma County, California, United States as of the date shown above. A total of 456 species have been recorded. In addition, a record of Veery is currently being reviewed by the California Bird Records Committee and will be added to the Sonoma County list if accepted. The species names and order follow the eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2018 which is "based largely on decisions of the North American Checklist Committee (NACC), through the Fifty-ninth supplement to the American Ornithological Society’s Check-list of North American Birds (July 2018)." Anatidae (Ducks, Geese, and Waterfowl) Emperor Goose Anser canagicus Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Ross's Goose Anser rossii Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons Brant Branta bernicla Cackling Goose Branta hutchinsii Canada Goose Branta canadensis Tundra Swan Cygnus columbianus Wood Duck Aix sponsa Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Gadwall Mareca strepera Eurasian Wigeon Mareca penelope American Wigeon Mareca americana Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Northern Pintail Anas acuta Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Canvasback Aythya valisineria Redhead Aythya americana Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula Greater Scaup Aythya marila Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Steller's Eider Polysticta stelleri King Eider Somateria spectabilis Harlequin Duck Histrionicus histrionicus -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Bobcat Predation on Quail, Birds, and Mesomammals

BOBCAT PREDATION ON QUAIL, BIRDS, AND MESOMAMMALS Michael E. Tewes Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, MSC 218, Texas A&M University, Kingsville, TX 78363, USA Jennifer M. Mock Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, MSC 218, Texas A&M University, Kingsville, TX 78363, USA John H. Young Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Wildlife Diversity Program, 3000 IH 35 South, Suite 100, Austin, TX 78704, USA ABSTRACT We reviewed 54 scientific articles about bobcat (Lynx rufus) food habits to determine the occurrence of quail, birds, and mesopredators including red (Vulpes vulpes) and gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), raccoon (Procyon lotor), skunk (Mephitis spp.), and opossum (Didelphis virginianus). Quail (Colinus virginianus, Cyrtonyx montezumae, Callipepla squamata, C. gambelii, C. californica, Oreortyx pictus) were found in 9 diet studies and constituted Ͼ3% of the bobcat diet in only 2 of 54 studies. Birds occurred in 47 studies, but were also a minor dietary component in most studies. Although mesopredators were represented as bobcat prey in 33 of 47 studies, their percent occurrence within bobcat diets was low and showed regional patterns of occurrence. Bobcats are a minor quail predator, but felid effects on mesopredators and secondary impacts on quail need to be studied. Citation: M. E. Tewes, J. M. Mock, and J. H. Young. 2002. Bobcat predation on quail, birds, and mesomammals. Pages 65–70 in S. J. DeMaso, W. P. Kuvlesky, Jr., F. Herna´ndez, and M. E. Berger, eds. Quail V: Proceedings of the Fifth National Quail Symposium. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin, TX. Key words: bobcat, California quail, Callipepla californica, C. gambelii, C. -

21 Mountain Quail

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Grouse and Quails of North America, by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences May 2008 21 Mountain Quail Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscigrouse Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "21 Mountain Quail" (2008). Grouse and Quails of North America, by Paul A. Johnsgard. 23. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscigrouse/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grouse and Quails of North America, by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictzls (Douglas) 1829 OTHER VERNACULAR NAMES EODORNIZ de Montana, mountain partridge, painted quail, plumed quail, San Pedro quail. RANGE Resident in the western United States from southern Washington and southwestern Idaho east to Nevada and south to Baja California. Also introduced in western Washington and western British Columbia (Van- couver Island). Introduced but of uncertain status in western Colorado. SUBSPECIES (ex A.O. U. Check-list) 0. p. pictus (Douglas): Sierra mountain quail. Resident in mountain regions of extreme western Nevada west to the west side of the Cascade Range in southern Washington and south to the Sierra Nevada and inner Coast ranges of California. 0. p. palrneri Oberholser: Coast mountain quail. Resident from south- western Washington south through western Oregon to northwestern San Luis Obispo County, California. -

Western Regional News

. Western x'A Regional News Founded in 1925 SERVING WBBA reviews from participants. WBBA members not EFFECTIVE 11 SEP 04 enrolledin that workshopwere able to visit KBO's banding stations, where observation and assistance were welcomed. Steve Howelrs hum- At our annual meeting in September, the mingbirdidentification workshop helped banders membershipapproved the followingslate of people and birdersalike to separatesimilar species. And, to lead WBBA for the comingyear. as always,informal chats with colleaguesin the President.' Gary Blevins hallways and during meals rounded out a fine 1st Vice Pres.: John Alexander weekend. 2nd Vice Pres.: Diana Humpie Secretary: Mike Boyles Selected abstracts from the meeting will be Treasurer: Tricia Campbell publishedin NABB 29(4). Membership: Ken Burton Outreach: Walter Sakai Next year's meeting is scheduledfor the first Past President.' Ken Burton weekend in October in Camarillo, CA. NABC Rep.: John Alexander NABC Air.: Jim Tietz Editor: Kay Loughman BIRDS BANDED in 2003: At Large: C. J. Ralph The WBBAAnnual Report ASHLAND MEETING 2004 TheWestern Bird Banding Association isextremely gratefulto Chris Otahal for compilingthe 2003 Glorious weather, educational workshops, AnnualBanding Report and to Ken Burtonand Rita stimulatingpapers and presentations,and a wide Colwellfor helpingwith p roofreadingthe final selectionof field trips helped to make our 79th document.Compiling and proofreading this report annualmeeting a huge success. Thanks are due takes an enormous amount of volunteer time and to John Alexander and the staff and volunteers at effort. We also thank all the banders that took time Klamath Bird Observatory,who really outdid out of their busy livesto forwarddata to Chris. The themselvesin coordinatingand producingthis numberof bandersreporting data, 179,was lower meeting held jointly with Western Field than 2002.