Augmented Reality Jon Peddie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring How Bi-Directional Augmented Reality Gaze Visualisation Influences Co-Located Symmetric Collaboration

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 14 June 2021 doi: 10.3389/frvir.2021.697367 Eye See What You See: Exploring How Bi-Directional Augmented Reality Gaze Visualisation Influences Co-Located Symmetric Collaboration Allison Jing*, Kieran May, Gun Lee and Mark Billinghurst Empathic Computing Lab, Australian Research Centre for Interactive and Virtual Environment, STEM, The University of South Australia, Mawson Lakes, SA, Australia Gaze is one of the predominant communication cues and can provide valuable implicit information such as intention or focus when performing collaborative tasks. However, little research has been done on how virtual gaze cues combining spatial and temporal characteristics impact real-life physical tasks during face to face collaboration. In this study, we explore the effect of showing joint gaze interaction in an Augmented Reality (AR) interface by evaluating three bi-directional collaborative (BDC) gaze visualisations with three levels of gaze behaviours. Using three independent tasks, we found that all bi- directional collaborative BDC visualisations are rated significantly better at representing Edited by: joint attention and user intention compared to a non-collaborative (NC) condition, and Parinya Punpongsanon, hence are considered more engaging. The Laser Eye condition, spatially embodied with Osaka University, Japan gaze direction, is perceived significantly more effective as it encourages mutual gaze Reviewed by: awareness with a relatively low mental effort in a less constrained workspace. In addition, Naoya Isoyama, Nara Institute of Science and by offering additional virtual representation that compensates for verbal descriptions and Technology (NAIST), Japan hand pointing, BDC gaze visualisations can encourage more conscious use of gaze cues Thuong Hoang, Deakin University, Australia coupled with deictic references during co-located symmetric collaboration. -

Advanced Displays and Techniques for Telepresence COAUTHORS for Papers in This Talk

Advanced Displays and Techniques for Telepresence COAUTHORS for papers in this talk: Young-Woon Cha Rohan Chabra Nate Dierk Mingsong Dou Wil GarreM Gentaro Hirota Kur/s Keller Doug Lanman Mark Livingston David Luebke Andrei State (UNC) 1994 Andrew Maimone Surgical Consulta/on Telepresence Federico Menozzi EMa Pisano, MD Henry Fuchs Kishore Rathinavel UNC Chapel Hill Andrei State Eric Wallen, MD ARPA-E Telepresence Workshop Greg Welch Mary WhiMon April 26, 2016 Xubo Yang Support gratefully acknowledged: CISCO, Microsoft Research, NIH, NVIDIA, NSF Awards IIS-CHS-1423059, HCC-CGV-1319567, II-1405847 (“Seeing the Future: Ubiquitous Computing in EyeGlasses”), and the BeingThere Int’l Research Centre, a collaboration of ETH Zurich, NTU Singapore, UNC Chapel Hill and Singapore National Research Foundation, Media Development Authority, and Interactive Digital Media Program Office. 1 Video Teleconferencing vs Telepresence • Video Teleconferencing • Telepresence – Conven/onal 2D video capture and – Provides illusion of presence in the display remote or combined local&remote space – Single camera, single display at each – Provides proper stereo views from the site is common configura/on for precise loca/on of the user Skype, Google Hangout, etc. – Stereo views change appropriately as user moves – Provides proper eye contact and eye gaze cues among all the par/cipants Cisco TelePresence 3000 Three distant rooms combined into a single space with wall-sized 3D displays 2 Telepresence Component Technologies • Acquisi/on (cameras) • 3D reconstruc/on Cisco -

New Realities Risks in the Virtual World 2

Emerging Risk Report 2018 Technology New realities Risks in the virtual world 2 Lloyd’s disclaimer About the author This report has been co-produced by Lloyd's and Amelia Kallman is a leading London futurist, speaker, Amelia Kallman for general information purposes only. and author. As an innovation and technology While care has been taken in gathering the data and communicator, Amelia regularly writes, consults, and preparing the report Lloyd's does not make any speaks on the impact of new technologies on the future representations or warranties as to its accuracy or of business and our lives. She is an expert on the completeness and expressly excludes to the maximum emerging risks of The New Realities (VR-AR-MR), and extent permitted by law all those that might otherwise also specialises in the future of retail. be implied. Coming from a theatrical background, Amelia started Lloyd's accepts no responsibility or liability for any loss her tech career by chance in 2013 at a creative or damage of any nature occasioned to any person as a technology agency where she worked her way up to result of acting or refraining from acting as a result of, or become their Global Head of Innovation. She opened, in reliance on, any statement, fact, figure or expression operated and curated innovation lounges in both of opinion or belief contained in this report. This report London and Dubai, working with start-ups and corporate does not constitute advice of any kind. clients to develop connections and future-proof strategies. Today she continues to discover and bring © Lloyd’s 2018 attention to cutting-edge start-ups, regularly curating All rights reserved events for WIRED UK. -

Gameplay in Mixed Reality: How It Differs from Mobile Gameplay Weerachet Sinlapanuntakul, William J

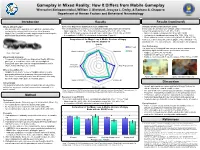

Gameplay in Mixed Reality: How It Differs from Mobile Gameplay Weerachet Sinlapanuntakul, William J. Shelstad, Jessyca L. Derby, & Barbara S. Chaparro Department of Human Factors and Behavioral Neurobiology Introduction Results Results (continued) What is Mixed Reality? Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (GUESS-18) Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) • Mixed Reality (MR) expands a user’s physical environment by The overall satisfaction scores (out of 56) indicated a statistically significance between: In this study, the 20-minute use of Magic Leap is resulted with overlaying the real-world with interactive virtual elements • Magic Leap (M = 42.31, SD = 5.61) and mobile device (M = 38.31, SD = 5.49) concerning symptoms (M = 16.83, SD = 15.51): • Magic Leap 1 is an MR wearable spatial computer that brings the • With α = 0.05, Magic Leap was rated with higher satisfaction, t(15) = 3.09, p = 0.007. • Nausea is considered minimal (M = 9.54, SD = 12.07) physical and digital worlds together (Figure 1). • A comparison of GUESS-18 subscales is shown below (Figure 2). • Oculomotor is considered concerning (M = 17.53, SD = 16.31) • Disorientation is considered concerning (M = 16.53, SD = 17.02) Comparison of the Magic Leap & Mobile Versions of Angry Total scores can be associated with negligible (< 5), minimal (5 – 10), Birds with the GUESS-18 significant (10 – 15), concerning (15 – 20), and bad (> 20) symptoms. Usability 7 Magic Leap User Performance 6 The stars (out of 3) collected from each level played represented a statistically significant difference in performance outcomes: Visual Aesthetics 5 Narratives Mobile Figure 1. -

The Openxr Specification

The OpenXR Specification Copyright (c) 2017-2021, The Khronos Group Inc. Version 1.0.19, Tue, 24 Aug 2021 16:39:15 +0000: from git ref release-1.0.19 commit: 808fdcd5fbf02c9f4b801126489b73d902495ad9 Table of Contents 1. Introduction . 2 1.1. What is OpenXR?. 2 1.2. The Programmer’s View of OpenXR. 2 1.3. The Implementor’s View of OpenXR . 2 1.4. Our View of OpenXR. 3 1.5. Filing Bug Reports. 3 1.6. Document Conventions . 3 2. Fundamentals . 5 2.1. API Version Numbers and Semantics. 5 2.2. String Encoding . 7 2.3. Threading Behavior . 7 2.4. Multiprocessing Behavior . 8 2.5. Runtime . 8 2.6. Extensions. 9 2.7. API Layers. 9 2.8. Return Codes . 16 2.9. Handles . 23 2.10. Object Handle Types . 24 2.11. Buffer Size Parameters . 25 2.12. Time . 27 2.13. Duration . 28 2.14. Prediction Time Limits . 29 2.15. Colors. 29 2.16. Coordinate System . 30 2.17. Common Object Types. 33 2.18. Angles . 36 2.19. Boolean Values . 37 2.20. Events . 37 2.21. System resource lifetime. 42 3. API Initialization. 43 3.1. Exported Functions . 43 3.2. Function Pointers . 43 4. Instance. 47 4.1. API Layers and Extensions . 47 4.2. Instance Lifecycle . 53 4.3. Instance Information . 58 4.4. Platform-Specific Instance Creation. 60 4.5. Instance Enumerated Type String Functions. 61 5. System . 64 5.1. Form Factors . 64 5.2. Getting the XrSystemId . 65 5.3. System Properties . 68 6. Path Tree and Semantic Paths. -

Virtual Reality: Measuring User Experiences, Providing a Justification for Investment

Virtual Reality: Measuring User Experiences, Providing a Justification for Investment a white paper by The value of immersive experiences is widely recognized, but brands hesitate to invest without a way to measure effectiveness and justify the cost. Isobar, in collaboration with the MIT Media Lab, has developed a way to capture and analyze behavioral and biometric data, and understand emotional states created by virtual, augmented, and mixed reality experiences. Suddenly, brands have precise, sensitive methods that measure success. Companies working with us can know consumers better than they know themselves, in the moment, like never before. Virtual Reality: Measuring User Experiences, Justifying Investment Virtual, augmented, and mixed/merged reality have already begun to transform our world. New standards are being set in gaming and entertainment. Education is creating more effective ways to teach. Retailers are using virtual, augmented, and mixed/merged reality to experiment with new store layouts. They’re also using consumer-facing applications to let people try clothing, makeup, and new paint colors on their walls. New digital experiences are making life more interesting, but also creating confusion and apprehension for brands. They’re struggling to justify the cost and complexity without a way to measure effectiveness — and account for the changes that will impact the market in the next few years. Virtual reality has traction. But like all new media formats, it has a chicken-and-egg problem. In 2016, sales of VR headsets fell shy of original forecasts. The total number of units (not including their smartphone cousins) are estimated at 1.2 million — much less than the 2 million predicted. -

Virtual & Augmented Reality

EXCERPTED FROM THE ORIGINAL: See inside cover for details. FINANCIAL BACKING GLOBAL INTEREST SHIPPING OUT SELLING OUT INTEREST IN THE PAST READY TO BUILD A WAVE OF CONTENT ON THE WAY RETAIL VALUE HOME REDESIGN, REIMAGINED EASIER TO IMAGINE YOURSELF AT HOME Video • Jaunt The Ecosystem • NextVR Virtual Reality / Augmented Reality • VRSE • Oculus Story Studio • GoPro • IG Port Processors Games • TI Applications • Sony • Qualcomm • Ubisoft 3D Audio • STMicro Graphics • CCP Games • Nvidia • TI • Realtek • Oculus Story Studio • AMD • Wolfson • Himax • Tammeka Games • Qualcomm • Realtek • MediaTek • Pixel Titans • Intel • Capcom Augmented Reality Virtual Reality Engineering • Microsoft HoloLens • Facebook Oculus Head–mounted devices • Autodesk • Google Glass • Samsung Gear VR • Dassault Systèmes • Magic Leap • Google Cardboard • IrisVR • Atheer • HTC Vive • Visidraft • Osterhout Design • Sony PSVR • MakeVR Memory Group • Vuzix iWear (DRAM/SSD) • VR Union Claire • Micron Healthcare • Samsung • Psious • SK Hynix • zSpace • Toshiba • Conquer Mobile • 3D Systems Social • Altspace VR • High Fidelity • Podrift Commerce • Sixense {shopping} • Matterport {real estate} Display • Samsung • JDI Cameras • Himax • 360Heros • Crystal • GoPro Odyssey 3D Lenses • Nokia OZO • Wearality • Jaunt NEO • Zeiss • Matterport Pro 3D Components • Canon • Nikon Haptics • Largan • Alps Position/ Room Tracker • AAC • Hon Hai • Nidec • Pegatron • Flex • Jabil • HTC Motion Sensors • Leap Motion • InvenSense • TI • STMicro • Honeywell The Ecosystem Virtual Reality / Augmented -

Towards Mobile Immersive Analysis: a Study of Applications

Towards Mobile Immersive Analysis: A Study of Applications Aidong Lu∗ Jian Huangy Shaoting Zhangz University of North Carolina at Charlotte University of Tennessee at Knoxville University of North Carolina at Charlotte Chuang Wangx Weichao Wang{ University of North Carolina at Charlotte University of North Carolina at Charlotte ABSTRACT While virtual reality has been studied for years [61, 57], the three The latest new technologies of virtual and mixed realities are ready key features differentiate mobile and immersive environments from to be commercialized. Their innovative communication channels the traditional VR technologies significantly. have created new opportunities and challenges for visualization and visual analytics. At this stage, it is important to understand the state-of-the-art of relevant technologies as well as the impacts to the research fields. This position paper presents the key features of mobile, immersive environments that are different from tradi- tional visualization and visual analytics systems. Through a study of applications in the mixed reality, we present a rich example set of capabilities and applications that address discovery and visual com- munication in real-world uses. We hope that this work will provide references and promote the research on the topic of immersive vi- sualization and visual analytics. Index Terms: I.3.6 [Computer Graphics]: Methodology and Techniques—Interaction techniques; I.3.8 [Computer Graphics]— Applications 1 INTRODUCTION Over the past few years, newly developed technologies, includ- Figure 1: Examples of Microsoft HoloLens [33] illustrate the mobile ing big data, cloud, mobile and social networks, have significantly and immersive environments, providing innovative tools as well as changed our everyday lives. -

Mixed Reality & Microsoft Hololens

Mixed Reality & Microsoft HoloLens Laboratorio di Realtà Virtuale Manuel Pezzera – [email protected] Mixed Reality • “Mixed reality (MR) is a spectrum of immersive experiences, connecting and blending physical and digital worlds together in augmented-reality and virtual-reality applications” [cit. Microsoft] Mixed Reality Augmented and Virtual Reality • Virtual Reality: it tricks your eyes into thinking that you are somewhere else. • Augmented reality: it is an extra dimension over VR since it can show the real world around wearer with graphic overlayed. • AR can also totally immerse user just like VR by simply showing pixels everywhere with no transparency to the real world. • In virtual world, users are best advised to stay seated to avoid collision with physical objects which they cannot see in the real world. What is a hologram? • A hologram is an object like any other object in the real world, with only one difference: instead of being made of physical matter, a hologram is made entirely of light. • Holographic objects can be viewed from different angles and distances, just like physical objects. They can also interact with the environment (e.g., bouncing ball on a table) • Hologram do not offer any physical resistance when touched or pushed because they don’t have a mass. Mixed reality vs Augmented Reality • MR can be mentioned as an enhanced form of Augmented Reality (AR). In AR the visible natural environment is overlaid with a layer of digital content. • But the case is slightly different with MR, as virtual objects are integrated into and responsive to the real world. For instance, a virtual ball under your desk would be blocked from a user’s view unless he bends. -

An Augmented Reality U-Academy Module: from Basic Principles to Connected…

Special Focus Paper—An Augmented Reality U-Academy Module: From Basic Principles to Connected… An Augmented Reality U-Academy Module: From Basic Principles to Connected Subjects https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v11i5.7074 Paulo Menezes University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal [email protected] Abstract—A module for learning about virtual and augmented reality is be- ing developed under the U-Academy project. The module is composed of three parts. The first part is an introduction to the basic concepts of virtual and aug- mented reality with the help of illustrative examples. The second part presents some of the current uses of augmented reality and its prospective use in several areas that range from industry to medicine. The final part aims at those students interested in the insights of this technology by presenting the underlying con- cepts such as: camera models, computer graphics, pattern detection and pose es- timation from inertial sensors or camera images. Keywords—Augmented Reality, Cognitive Processes, Direct Manipulation, Hand Tracking 1 Introduction Augmented reality has recently received an enormous amount of attention from both the general public and companies. Naturally, the game industry has been quite attentive to the long promised technologies to support it. There are indeed several companies doing important investments in the development of products for support- ing augmented reality (AR), like Microsoft Hololens, Vufuria, Magic Leap, and Meta 2, or for virtual reality (VR) such as HTC Vibe and Oculus Rift. As a matter of fact, some technical difficulties have limited the achievable quality of visualization in AR, and for this reason its inclusion in the games offered by the major players in this industry has been postponed until recently. -

1-2-4 Openxr

© The Khronos® Group Inc. 2018 - Page 1 Unifying Reality Standardizing XR: OpenXR Brent E. Insko, PhD Lead VR Architect at Intel & OpenXR Working Group Chair 3GPP, VRIF & AIS Workshop on VR Ecosystem & Standards, April 2019 © Khronos® Group Inc. 2019 - Page 2 Agenda • What is OpenXR? • A Brief History of the Standard • What are the Problems we are trying to Solve • OpenXR Timeline of Development • Provisional Release • What’s Next? • Recap • Call To Action • Questions © The Khronos® Group Inc. 2018 - Page 3 OpenXR Provisional 0.90 Released! Press announcement Updated landing page © The Khronos® Group Inc. 2018 - Page 4 What is OpenXR? OpenXR is a royalty-free, open standard that provides high-performance access to Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR)—collectively known as XR—platforms and devices. © The Khronos® Group Inc. 2018 - Page 5 A Brief History of OpenXR • Among the first VR hardware available 2016 • Need applications… - Each platform provided an SDK to interface with the hardware - Each was different from the other © The Khronos® Group Inc. 2018 - Page 6 XR Ecosystem Fragmentation •Increased development time and therefore cost. •Increased validation overhead and therefore cost. •Time and resources spent developing one title, impacts developers’ ability to create more titles. © The Khronos® Group Inc. 2018 - Page 7 Major XR Runtimes © The Khronos® Group Inc. 2018 - Page 8 VR Barriers to Adoption… •Content •Comfort •Cost © The Khronos® Group Inc. 2018 - Page 9 OpenXR • Recognizing the problem, several companies got together in late 2016 / early 2017 and formed the OpenXR working group in Khronos. Virtual Reality V A Augmented Reality © The Khronos® Group Inc. -

How to Get Started with AR/MR/VR

Madeline Wrable GIS Specialist CLSTL’19 pngtree.com 1 Content • GIS & Data Lab • VR Pilot Project Story • What is VR • VR hard/software • Getting started pngtree.com 2 Content • GIS & Data Lab • VR Pilot Project Story • What is VR • VR hard/software • Getting started pngtree.com 3 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Getty Images 4 Rotch Library Getty Images 5 MIT GIS Services: GIS & Data Lab • GIS Lab • Additional software • GIS data repository, GeoWeb • One-on-one help • Workshops Credit: Lisa Sweeney 6 Content • GIS & Data Lab • VR Pilot Project Story • What is VR • VR hard/software • Getting started pngtree.com 7 VR Pilot Project Story Adapted from “Reality Bytes: VR and AR” – 8 Matt Bernhardt, MIT Libraries Jesussanz/Getty Creative 8 VR Pilot Project Story The MIT Libraries Experimental Collections Fund Supports projects using library datasets in new ways. I used it for a drone-pilot-project. Do you have any ideas? Adapted from “Reality Bytes: VR and AR” – 9 Matt Bernhardt, MIT Libraries Jesussanz/Getty Creative 9 VR Pilot Project Story The MIT Libraries Experimental Collections Fund Supports projects using library I wonder if virtual reality (VR) datasets in new ways. would be a good fit… I used it for a drone-pilot-project. Do you have any ideas? Adapted from “Reality Bytes: VR and AR” – 10 Matt Bernhardt, MIT Libraries Jesussanz/Getty Creative 10 Content • GIS & Data Lab • VR Pilot Project Story • What is VR • VR hard/software • Getting started pngtree.com 11 Facebook F8 developer’s conference, 2015 12 History of Immersive Reality