Playing with Virtual Reality: Early Adopters of Commercial Immersive Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advances in Artificial Reality and Tele-Existence

R. Liang, Z. Pan, A. Cheok, M. Haller, R.W.H. Lau, H. Saito (Eds.) Advances in Artificial Reality and Tele-Existence 16th International Conference on Artificial Reality and Telexistence, ICAT 2006, Hangzhou, China, November 28 - December 1, 2006, Proceedings Series: Information Systems and Applications, incl. Internet/Web, and HCI, Vol. 4282 This book constitutes the refereed proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Artificial Reality and Telexistence, ICAT 2006, held in Hangzhou, China in November/ December 2006. The 138 revised full papers presented were carefully reviewed and selected from a total of 523 submissions. The papers are organized in topical sections on anthropomorphic intelligent robotics, artificial life, augmented reality, mixed reality, distributed and collaborative VR system, haptics, human factors of VR, innovative applications of VR, motion tracking, real time computer simulation, tools and technique for modeling VR systems, ubiquitous/wearable computing, virtual heritage, virtual medicine and health science, virtual reality, as well as VR interaction and navigation techniques. 2006, XLVI, 1350 p. In 2 volumes, not available separately. Printed book Softcover ▶ 159,99 € | £144.00 | $219.00 ▶ *171,19 € (D) | 175,99 € (A) | CHF 213.21 eBook Available from your bookstore or ▶ springer.com/shop MyCopy Printed eBook for just ▶ € | $ 24.99 ▶ springer.com/mycopy Order online at springer.com ▶ or for the Americas call (toll free) 1-800-SPRINGER ▶ or email us at: [email protected]. ▶ For outside the Americas call +49 (0) 6221-345-4301 ▶ or email us at: [email protected]. The first € price and the £ and $ price are net prices, subject to local VAT. Prices indicated with * include VAT for books; the €(D) includes 7% for Germany, the €(A) includes 10% for Austria. -

Audio for Virtual and Augmented Reality

2016 AES CONFERENCE AUDIO FOR VIRTUAL AND AUGMENTED REALITY FRIDAY, SEPT 30 THRU SATURDAY, OCT 1 LOS ANGELES CONVENTION CENTER CONFERENCE PROGRAM PLATINUM SPONSORS GOLD SPONSORS SPONSORS MESSAGE FROM THE CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Welcome to the first AES International Conference on Audio for Virtual and Augmented Reality! We are really proud to present this amazing technical program, which is the result of many months of extremely hard teamwork. We aimed for the best content we could possibly provide, and here you have it. We are extremely thankful to our great presenters, authors, keynote speakers and sponsors. Together, we made this possible and we sincerely hope you will take away a lot of useful information. Also, I´d like to extend our special thanks to our delegates, coming from all over the world to ANDRES MAYO attend this truly unique event, and to our really hard working team of volunteers, which ultimately made it possible to Conference Co-chair pack this awesome quality and quantity of knowledge in 2 full days crammed with papers, workshops, tutorials and even a technical showcase. Welcome to the show! I would like to extend a warm welcome to all of our delegates, authors, presenters and sponsors. This conference has been a dream of Andres’ and mine since May of 2015. The world of VR / AR has grown so quickly, so fast that we knew we had to bring a conference dedicated specifically to this topic to the audio community. We could not have done this without the hard work and dedication of an incredible conference committee. -

Creating Accessibility in VR with Reused Motion Input

Replay to Play: Creating Accessibility in VR with Reused Motion Input A Technical Report presented to the faculty of the School of Engineering and Applied Science University of Virginia by Cody Robertson May 8, 2020 On my honor as a University student, I have neither given nor received unauthorized aid on this assignment as defined by the Honor Guidelines for Thesis-Related Assignments. Signed: ___________________________________________________ Approved: ______________________________________ Date _______________________ Seongkook Heo, Department of Computer Science Replay to Play: Creating Accessibility in VR with Reused Motion Input Abstract Existing virtual reality (VR) games and applications tend not to factor in accommodations for varied levels of user ability. To enable users to better engage with this technology, a tool was developed to record and replay captured user motion to reduce the strain of complicated gross motor motions to a simple button press. This tool allows VR users with any level of motor impairment to create custom recordings of the motions they need to play VR games that have not designed for such accessibility. Examples of similar projects as well as recommendations for improvements are given to help round out the design space of accessible VR design. Introduction In many instances, high-end in-home virtual reality is synonymous with a head-mounted display (HMD) on the user’s face and motion-tracked controllers, simulating the hand’s ability to grip and hold objects, in a user’s hands. This is the case with all forms of consumer available HMD that is driven by a traditional computer rather than an integrated computer, including the Oculus Rift, Valve Index, HTC Vive, the variously produced Windows Mixed Reality HMDs, and Playstation VR with the Move Controllers. -

VR Headset Comparison

VR Headset Comparison All data correct as of 1st May 2019 Enterprise Resolution per Tethered or Rendering Special Name Cost ($)* Available DOF Refresh Rate FOV Position Tracking Support Eye Wireless Resource Features Announced Works with Google Subject to Mobile phone 5.00 Yes 3 60 90 None Wireless any mobile No Cardboard mobile device required phone HP Reverb 599.00 Yes 6 2160x2160 90 114 Inside-out camera Tethered PC WMR support Yes Tethered Additional (*wireless HTC VIVE 499.00 Yes 6 1080x1200 90 110 Lighthouse V1 PC tracker No adapter support available) HTC VIVE PC or mobile ? No 6 ? ? ? Inside-out camera Wireless - No Cosmos phone HTC VIVE Mobile phone 799.00 Yes 6 1440x1600 75 110 Inside-out camera Wireless - Yes Focus Plus chipset Tethered Additional HTC VIVE (*wireless tracker 1,099.00 Yes 6 1440x1600 90 110 Lighthouse V1 and V2 PC Yes Pro adapter support, dual available) cameras Tethered All features HTC VIVE (*wireless of VIVE Pro ? No 6 1440x1600 90 110 Lighthouse V1 and V2 PC Yes Pro Eye adapter plus eye available) tracking Lenovo Mirage Mobile phone 399.00 Yes 3 1280x1440 75 110 Inside-out camera Wireless - No Solo chipset Mobile phone Oculus Go 199.00 Yes 3 1280x1440 72 110 None Wireless - Yes chipset Mobile phone Oculus Quest 399.00 No 6 1440x1600 72 110 Inside-out camera Wireless - Yes chipset Oculus Rift 399.00 Yes 6 1080x1200 90 110 Outside-in cameras Tethered PC - Yes Oculus Rift S 399.00 No 6 1280x1440 90 110 Inside-out cameras Tethered PC - No Pimax 4K 699.00 Yes 6 1920x2160 60 110 Lighthouse Tethered PC - No Upscaled -

Evaluation of Virtual Reality Tracking Systems Underwater

International Conference on Artificial Reality and Telexistence Eurographics Symposium on Virtual Environments (2019) Y. Kakehi and A. Hiyama (Editors) Evaluation of Virtual Reality Tracking Systems Underwater Raphael Costa1,Rongkai Guo2,and John Quarles1 1University of Texas at San Antonio, USA 2Kennesaw State University, USA Abstract The objective of this research is to compare the effectiveness of various virtual reality tracking systems underwater. There have been few works in aquatic virtual reality (VR) - i.e., VR systems that can be used in a real underwater environment. Moreover, the works that have been done have noted limitations on tracking accuracy. Our initial test results suggest that inertial measurement units work well underwater for orientation tracking but a different approach is needed for position tracking. Towards this goal, we have waterproofed and evaluated several consumer tracking systems intended for gaming to determine the most effective approaches. First, we informally tested infrared systems and fiducial marker based systems, which demonstrated significant limitations of optical approaches. Next, we quantitatively compared inertial measurement units (IMU) and a magnetic tracking system both above water (as a baseline) and underwater. By comparing the devices’ rotation data, we have discovered that the magnetic tracking system implemented by the Razer Hydra is approximately as accurate underwater as compared to a phone-based IMU. This suggests that magnetic tracking systems should be further explored as a possibility -

Exploring How Bi-Directional Augmented Reality Gaze Visualisation Influences Co-Located Symmetric Collaboration

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 14 June 2021 doi: 10.3389/frvir.2021.697367 Eye See What You See: Exploring How Bi-Directional Augmented Reality Gaze Visualisation Influences Co-Located Symmetric Collaboration Allison Jing*, Kieran May, Gun Lee and Mark Billinghurst Empathic Computing Lab, Australian Research Centre for Interactive and Virtual Environment, STEM, The University of South Australia, Mawson Lakes, SA, Australia Gaze is one of the predominant communication cues and can provide valuable implicit information such as intention or focus when performing collaborative tasks. However, little research has been done on how virtual gaze cues combining spatial and temporal characteristics impact real-life physical tasks during face to face collaboration. In this study, we explore the effect of showing joint gaze interaction in an Augmented Reality (AR) interface by evaluating three bi-directional collaborative (BDC) gaze visualisations with three levels of gaze behaviours. Using three independent tasks, we found that all bi- directional collaborative BDC visualisations are rated significantly better at representing Edited by: joint attention and user intention compared to a non-collaborative (NC) condition, and Parinya Punpongsanon, hence are considered more engaging. The Laser Eye condition, spatially embodied with Osaka University, Japan gaze direction, is perceived significantly more effective as it encourages mutual gaze Reviewed by: awareness with a relatively low mental effort in a less constrained workspace. In addition, Naoya Isoyama, Nara Institute of Science and by offering additional virtual representation that compensates for verbal descriptions and Technology (NAIST), Japan hand pointing, BDC gaze visualisations can encourage more conscious use of gaze cues Thuong Hoang, Deakin University, Australia coupled with deictic references during co-located symmetric collaboration. -

Hyperreality and Virtual Worlds: When the Virtual Is Real

sphera.ucam.edu ISSNe: 2695-5725 ● Número 19 ● Vol.II ● Año 2019 ● pp. 36-58 Hyperreality and virtual worlds: when the virtual is real Paulo M. Barroso, Polytechnic Institute of Viseu (Portugal) [email protected] Received: 12/11/19 ● Accepted: 10/12/19 ● Published: 19/12/19 How to reference this paper: Barroso, Paulo M. (2019). Hyperreality and virtual worlds: when the virtual is real, Sphera Publica, 2(19), 36‐58. Abstract This article questions what is hyperreality and underlines the role of the signs/images fostering the perception of a virtual world. It argues the potentiality of signs as artefacts. Starting from Agamben’s perspective regarding contemporary, the hyperreality is understood as a modern, visual and mass manifestation of the need for simulacra in a non-referential virtual world. How hyperreality, spectacle, simulation, and appearance emerge out of reality? What is authentic or real are issues raised using images and technological devices. The images are popular and amplify the effects of distraction and social alienation. The image is immediately absorbed, spectacular, attractive, a peculiar ready-to-think that eliminates or dilutes the concepts and produces a fast culture. Through a reflexive strategy, this article is conceptual (it has no case study or empirical work) and has the purpose of problematize the experience of hyperreality, which is reshaping and restructuring patterns of social life and social interdependence, and the ways we see, think, feel, act or just mean and interpret the reality. Keywords Hyperreality, image, real, virtual worlds, technology Barroso Hiperrealidad y mundos virtuales Hiperrealidad y mundos virtuales: cuando lo virtual es real Paulo M. -

Ubisoft® Celebrates 30 Years of Creating Games at E3 2016

Ubisoft® Celebrates 30 Years of Creating Games at E3 2016 PARIS, FRANCE — June 2, 2016 — Today, Ubisoft reveals its plans for E3 2016, where its creative teams will proudly present highly anticipated titles such as Watch Dogs® 2, For Honor™ or Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon® Wildlands. They’ll also detail new content coming for live games and – as usual – unveil some surprises. The week will kick off with Ubisoft’s E3 2016 Conference, taking place on Monday, June 13 starting at 1 p.m. PDT and preceded by a 30-minute pre-show. E3 attendees can experience Ubisoft games at its booth (booth #1023, South Hall, Los Angeles Convention Center) from June 14 – 16. More than 1,700 fans also have the opportunity to play Ubisoft games and meet the development teams at the fourth-annual Ubisoft Lounge. “E3 is always a very special moment when everyone in the entertainment business does their best to amaze and engage gamers. For Ubisoft’s teams, it’s a period of pride and of anxious anticipation because they are finally showing off the games they’ve poured so much passion into, and receiving feedback from players and peers. Our industry has evolved so much in the past 30 years, but what hasn’t changed is my love and respect for the limitless passion and talent of developers and players alike,” said Yves Guillemot, co-founder and CEO, Ubisoft. “The video game industry continues to enjoy strong momentum, with powerful new platforms that enable more creativity, expression and imagination. More than ever, video games are showing how they will shape the future of entertainment. -

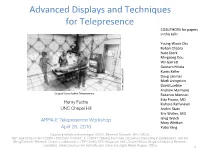

Advanced Displays and Techniques for Telepresence COAUTHORS for Papers in This Talk

Advanced Displays and Techniques for Telepresence COAUTHORS for papers in this talk: Young-Woon Cha Rohan Chabra Nate Dierk Mingsong Dou Wil GarreM Gentaro Hirota Kur/s Keller Doug Lanman Mark Livingston David Luebke Andrei State (UNC) 1994 Andrew Maimone Surgical Consulta/on Telepresence Federico Menozzi EMa Pisano, MD Henry Fuchs Kishore Rathinavel UNC Chapel Hill Andrei State Eric Wallen, MD ARPA-E Telepresence Workshop Greg Welch Mary WhiMon April 26, 2016 Xubo Yang Support gratefully acknowledged: CISCO, Microsoft Research, NIH, NVIDIA, NSF Awards IIS-CHS-1423059, HCC-CGV-1319567, II-1405847 (“Seeing the Future: Ubiquitous Computing in EyeGlasses”), and the BeingThere Int’l Research Centre, a collaboration of ETH Zurich, NTU Singapore, UNC Chapel Hill and Singapore National Research Foundation, Media Development Authority, and Interactive Digital Media Program Office. 1 Video Teleconferencing vs Telepresence • Video Teleconferencing • Telepresence – Conven/onal 2D video capture and – Provides illusion of presence in the display remote or combined local&remote space – Single camera, single display at each – Provides proper stereo views from the site is common configura/on for precise loca/on of the user Skype, Google Hangout, etc. – Stereo views change appropriately as user moves – Provides proper eye contact and eye gaze cues among all the par/cipants Cisco TelePresence 3000 Three distant rooms combined into a single space with wall-sized 3D displays 2 Telepresence Component Technologies • Acquisi/on (cameras) • 3D reconstruc/on Cisco -

Art and Hyperreality Alfredo Martin-Perez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2014-01-01 Art and Hyperreality Alfredo Martin-Perez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Martin-Perez, Alfredo, "Art and Hyperreality" (2014). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1290. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1290 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HYPERREALITY & ART A RECONSIDERATION OF THE NOTION OF ART ALFREDO MARTIN-PEREZ Department of Philosophy APPROVED: Jules Simon, Ph.D. Mark A. Moffett, Ph.D. Jose De Pierola, Ph.D. ___________________________________________ Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © By Alfredo Martin-Perez 2014 HYPERREALITY & ART A RECONSIDERATION OF THE NOTION OF ART by ALFREDO MARTIN-PEREZ Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Philosophy THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO December 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my daughters, Ruby, Perla, and Esmeralda, for their loving emo- tional support during the stressing times while doing this thesis, and throughout my academic work. This humble work is dedicated to my grandchildren. Kimberly, Angel, Danny, Freddy, Desiray, Alyssa, Noe, and Isabel, and to the soon to be born, great-grand daughter Evelyn. -

Daniel Amos and Me: the Power of Pop Culture and Autoethnography

Daniel Amos and Me: The Power of Pop Culture and Autoethnography ANDREW F. HERRMANN Nearly everyone I know has a relationship with something in popular culture, whether it is Buffy the Vampire Slayer, amassing The Astonishing X-Men comics, or collecting every version of every Star Wars movie. Relationships and pop culture: couldn’t that make an autoethnography? This is a short version of my relationship with a band, Daniel Amos. I am not in Daniel Amos. I don’t know the members of the band (although I am Facebook friends with them now). I first heard them in 1982 serendipitously. Or maybe it was destiny. Either way, they opened my eyes to the wonders, doubts, and excesses of my life, critiqued my faith, and brought me joy. I feel like I know them, and they me. Thirty-one years after first hearing them, I realize our relationship is one of the longest I have had. We grew up and are growing older together. Popular Culture Autoethnography? Pop culture and autoethnography: two terms seemingly at odds with each other. On the one side stands popular culture studies, with its interrogations of music (Albiez), television shows (Stern), video gaming (Dunn & Guadagno), movie genres (Carroll), characters (Herrmann, “C-can”) – including individuals who become “characters” (Herbig 133) – and its examinations of power and discourses in popular texts, broadly defined (Stern, Manning & Dunn). On the other side sits autoethnography, the narrative first-person examination of the self, used as a jumping off point to interrogate cultural practices (Holman Jones, Adams & Ellis). One examines culture and identity from the outside in, the other from the inside out. -

Ubisoft Studios

CREATIVITY AT THE CORE UBISOFT STUDIOS With the second largest in-house development staff in the world, Ubisoft employs around 8 000 team members dedicated to video games development in 29 studios around the world. Ubisoft attracts the best and brightest from all continents because talent, creativity & innovation are at its core. UBISOFT WORLDWIDE STUDIOS OPENING/ACQUISITION TIMELINE Ubisoft Paris, France – Opened in 1992 Ubisoft Bucharest, Romania – Opened in 1992 Ubisoft Montpellier, France – Opened in 1994 Ubisoft Annecy, France – Opened in 1996 Ubisoft Shanghai, China – Opened in 1996 Ubisoft Montreal, Canada – Opened in 1997 Ubisoft Barcelona, Spain – Opened in 1998 Ubisoft Milan, Italy – Opened in 1998 Red Storm Entertainment, NC, USA – Acquired in 2000 Blue Byte, Germany – Acquired in 2001 Ubisoft Quebec, Canada – Opened in 2005 Ubisoft Sofia, Bulgaria – Opened in 2006 Reflections, United Kingdom – Acquired in 2006 Ubisoft Osaka, Japan – Acquired in 2008 Ubisoft Chengdu, China – Opened in 2008 Ubisoft Singapore – Opened in 2008 Ubisoft Pune, India – Acquired in 2008 Ubisoft Kiev, Ukraine – Opened in 2008 Massive, Sweden – Acquired in 2008 Ubisoft Toronto, Canada – Opened in 2009 Nadeo, France – Acquired in 2009 Ubisoft San Francisco, USA – Opened in 2009 Owlient, France – Acquired in 2011 RedLynx, Finland – Acquired in 2011 Ubisoft Abu Dhabi, U.A.E – Opened in 2011 Future Games of London, UK – Acquired in 2013 Ubisoft Halifax, Canada – Acquired in 2015 Ivory Tower, France – Acquired in 2015 Ubisoft Philippines – Opened in 2016 UBISOFT PaRIS Established in 1992, Ubisoft’s pioneer in-house studio is responsible for the creation of some of the most iconic Ubisoft brands such as the blockbuster franchise Rayman® as well as the worldwide Just Dance® phenomenon that has sold over 55 million copies.