Sports Leagues' New Social Media Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 Spring FB MG

Virginia Tech Spring Football 2004 Underclassmen To Watch 11 Xavier Adibi 42 James Anderson 59 Barry Booker 89 Duane Brown 96 Noland Burchette 61 Reggie Butler 44 John Candelas LB • r-Fr. LB • r-Jr. DT • r-Fr. TE • r-Fr. DE • r-So. OT • Jr. TB • Jr. 57 Tripp Carroll 37 Chris Ceasar 16 Chris Clifton 87 David Clowney Jud Dunlevy 49 Chris Ellis 28 Corey Gordon C • r-Fr. CB • r-So. SE • r-Jr. FL • So. PK • r-Fr. DE • r-Fr. FS • r-Fr. 77 Brandon Gore 9Vince Hall 27 Justin Hamilton John Hedge 18 Michael Hinton 32 Cedric Humes 19 Josh Hyman OG • r-So. LB • r-Fr. FL • r-Jr. PK • r-Fr. ROV • r-Fr. TB • r-Jr. SE • r-Fr. 20 Mike Imoh 90 Jeff King 43 John Kinzer 56 Jonathan Lewis 88 Michael Malone 52 Jimmy Martin 69 Danny McGrath TB • Jr. TE • r-Jr. FB • r-Fr. DT • Jr. SE • r-So. OT • Jr. C • r-So. 29 Brian McPherson 15 Roland Minor 66 Will Montgomery 72 Jason Murphy 46 Brandon Pace 58 Chris Pannell 50 Mike Parham CB • r-So. CB • r-Fr. OG • r-Jr. OG • r-Jr. PK • r-So. OT • r-Jr. C • r-So. 80 Robert Parker 99 Carlton Powell 83 Matt Roan 75 Kory Robertson 36 Aaron Rouse 71 Tim Sandidge 23 Nic Schmitt FL • r-So. DT • r-Fr. TE • r-Fr. DT • r-Fr. LB • r-So. DT • r-Jr. P • r-So. 55 Darryl Tapp 41 Jordan Trott 5 Marcus Vick 30 Cary Wade 24 D.J. -

Killaz Football League 2009 Transactions 26-Feb-2010 05:59 PM Eastern Week 1

www.rtsports.com Killaz Football League 2009 Transactions 26-Feb-2010 05:59 PM Eastern Week 1 Fri., Mar 20 2009 5:48 p Marquis Patz Released Billy Miller NOR TE Owner Fri., Mar 20 2009 5:48 p Marquis Patz Released LaMont Jordan DEN RB Owner Tue., Apr 7 2009 7:29 p K.S. Coltz Acquired Jim Caldwell IND Head CoachCommissioner Sat., Jul 25 2009 4:58 p K.S. Coltz Released Deion Branch SEA WR Owner Sun., Jul 26 2009 2:16 p NP Patriotz Placed on IR Kerry Collins TEN QB Owner Sun., Jul 26 2009 2:17 p NP Patriotz Placed on IR Keary Colbert DET WR Owner Sun., Jul 26 2009 2:18 p NP Patriotz Placed on IR Daniel Graham DEN TE Owner Sun., Jul 26 2009 2:20 p NP Patriotz Released Warrick Dunn TAM RB Owner Sun., Jul 26 2009 3:15 p K.S. Coltz Placed on IR Matt Prater DEN K Commissioner Sun., Jul 26 2009 4:11 p NP Patriotz Placed on IR Donald Driver GNB WR Owner Sun., Jul 26 2009 5:14 p Marquis Patz Released Ahmad Bradshaw NYG RB Commissioner Sun., Jul 26 2009 5:14 p Marquis Patz Released Antonio Pittman STL RB Commissioner Sun., Jul 26 2009 5:16 p K.S. Coltz Acquired Ahmad Bradshaw NYG RB Commissioner Sun., Jul 26 2009 5:16 p K.S. Coltz Acquired Antonio Pittman STL RB Commissioner Sun., Jul 26 2009 11:30 p Team Pac-Man'z Fighterz Released Leonard Pope KAN TE Commissioner Sun., Jul 26 2009 11:31 p Team Pac-Man'z Fighterz Taken off IR Byron Leftwich TAM QB Commissioner Sun., Jul 26 2009 11:31 p Team Pac-Man'z Fighterz Released Stephen McGee DAL QB Commissioner Mon., Jul 27 2009 11:24 a Rodney's-Ninerz 4-06 Released John Phillips DAL TE Owner Mon., Jul 27 2009 5:57 p K.S. -

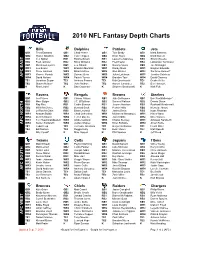

NFL Depth Chart Cheat Sheet

2010 NFL Fantasy Depth Charts Bills Dolphins Patriots Jets QB1 Trent Edwards QB1 Chad Henne QB1 Tom Brady QB1 Mark Sanchez QB2 Ryan Fitzpatrick QB2 Tyler Thigpen QB2 Brian Hoyer QB2 Mark Brunell RB1 C.J. Spiller RB1 Ronnie Brown RB1 Laurence Maroney RB1 Shonn Greene RB2 Fred Jackson RB2 Ricky Williams RB2 Fred Taylor RB2 LaDainian Tomlinson RB3 Marshawn Lynch RB3 Lex Hilliard RB3 Sammy Morris RB3 Joe McKnight WR1 Lee Evans WR1 Brandon Marshall WR1 Randy Moss WR1 Braylon Edwards WR2 Steve Johnson WR2 Brian Hartline WR2 Wes Welker WR2 Santonio Holmes* WR3 Roscoe Parrish WR3 Davone Bess WR3 Julian Edelman WR3 Jerricho Cotchery AFCEAST WR4 David Nelson WR4 Patrick Turner WR4 Brandon Tate WR4 David Clowney TE1 Jonathan Stupar TE1 Anthony Fasano TE1 Rob Gronkowski TE1 Dustin Keller TE2 Shawn Nelson* TE2 John Nalbone TE2 Aaron Hernandez TE2 Ben Hartsock K Rian Lindell K Dan Carpenter K Stephen Gostkowski K Nick Folk Ravens Bengals Browns Steelers QB1 Joe Flacco QB1 Carson Palmer QB1 Jake Delhomme QB1 Ben Roethlisberger* QB2 Marc Bulger QB2 J.T. O'Sullivan QB2 Seneca Wallace QB2 Dennis Dixon RB1 Ray Rice RB1 Cedric Benson RB1 Jerome Harrison RB1 Rashard Mendenhall RB2 Willis McGahee RB2 Bernard Scott RB2 Peyton Hillis RB2 Mewelde Moore RB3 Le'Ron McClain RB3 Brian Leonard RB3 James Davis RB3 Isaac Redman WR1 Anquan Boldin WR1 Chad Ochocinco WR1 Mohamed Massaquoi WR1 Hines Ward WR2 Derrick Mason WR2 Terrell Owens WR2 Josh Cribbs WR2 Mike Wallace WR3 T.J. Houshmandzadeh WR3 Andre Caldwell WR3 Chansi Stuckey WR3 Antwaan Randle El AFCNORTH WR4 Donte' -

2007 VIRGINIA TECH FOOTBALL 1 FACILITIES Last Year, the Hokies

facilities Duane Brown and Branden Ore Macho Harris Last year, the Hokies put together their third consecutive season with 10 or more victories and earned Tech’s 14th-straight bowl bid 2007 VIRGINIA TECH FOOTBALL 71 3 2006 in review 2006 Season in Review College Football’s Top Defense and a Strong Finish Land Hokies in Atlanta Following an Atlantic Coast going to come easily. After losing season schedule gave the Hokies Conference championship in 2004 more than half of its starters from some opportunities to work out and a Coastal Division title in an 11-2 Gator Bowl season in their kinks. 2005, the Virginia Tech Hokies 2005 — including a Tech-record The 2006 season kicked off had their work cut out for them to nine players chosen in the NFL with a 38-0 blanking of I-AA maintain the level of success they draft — there would be a lot of Northeastern on Sept. 2 at Lane had achieved during their first new faces on the field, and on Stadium before a new home two years in the league. Despite the sideline, as the team was also attendance record of 66,233. having some big holes to fill in breaking in four new assistant Glennon wasted no time cementing 2006, Tech was chosen to finish coaches. his role as the starter as he led second in the Coastal Division, Was Sean Glennon the the offense to touchdowns on its and was penciled into the No. Redshirt sophomore QB Sean right man for the quarterback first three possessions. He finished 17 slot in the preseason national Glennon improved throughout the position? Could Branden Ore fill the game 15-of-18 passing for rankings. -

Jets at Patriots Week13.Indb

2010 - GAME 11 AT PATRIOTS - 8:20 P.M. ET - ESPN NEW YORK JETS (9-2) AT NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (9-2) MON., DEC. 6 - GILLETTE STADIUM (68,756) MEDIA INFORMATION Contents MIKE TANNENBAUM ...................28 DEFENSIVE STATISTICS .............120 HEADLINES .................................. 2 REX RYAN .................................. 29 SEASON STATISTICS ..................121 BROADCAST COVERAGE ................ 2 COORDINATORS ......................... 30 BUILDING THE JETS ................. 122 2010 SCHEDULE .......................... 2 MARK SANCHEZ ......................... 31 TRANSACTIONS ........................ 123 PRONUNCIATION GUIDE ............... 2 OFFENSIVE LINE ......................... 34 DEPTH CHART ..........................124 STATISTICAL SNAPSHOT ................ 3 LaDAINIAN TOMLINSON .............. 36 ALPHABETICAL ROSTER ............127 SERIES BY THE NUMBERS ............ 3 SUCCESS ON THE ROAD ............. 38 NUMERICAL ROSTER ................128 SINGLE-GAME SERIES BESTS ........ 3 SANTONIO HOLMES .................... 39 PROBABLE STARTERS ...................4 DARRELLE REVIS ........................ 41 OVERVIEW BY POSITION ...............5 ANTONIO CROMARTIE ................. 41 INDIVIDUAL SERIES HIGHLIGHTS .. 7 DAVID HARRIS ............................ 42 GAME-BY-GAME VS. PATRIOTS ...... 9 BIOS NOT IN MEDIA GUIDE .........48 CONNECTIONS ........................... 12 UPDATED BIOS ...........................59 SUPPLEMENTAL STATS ............... 13 THE LAST TIME IT HAPPENED .....83 NEW MEADOWLANDS STADIUM .. 27 GAME REVIEWS ..........................84 -

Vol. 8, No. 2 September 2015

Vol. 8 No. 2, September 2015 • $4 The Official Publication of Virginia Tech Athletics WHAT’S INSIDE: South Florida products Luther Maddy and Dadi Nicolas have taken advantage of their opportunities PLAYING SOCCER WITH HER FEET - AND HER HEART Talented and versatile, Ashley Meier does it all for the Tech women’s soccer team and has throughout her career inside.hokiesports.com 1 LIFE FEELS GOOD WHEN YOU’RE A HOKIE FAN. Union is proud to be part of the Virginia Tech family. Come see us for all your banking needs and make a play for checking that’s really, really free. Union Bank & Trust 1-800-990-4828 UFM15011_082515 FB.indd 1 8/25/15 10:33 AM contents September 2015 • Vol. 8, No. 2 Hokie Club News | 2 Don't have a inside.hokiesports.com News & Notes | 6 Jimmy Robertson Baseball center named after former Tech AD subscription? Editor From the Editor’s Desk | 9 Grimm returns to begin career in coaching Marc Mullen Editorial Assistant Behind the Mic – Jon Laaser | 10 Subscribe today! Laaser and Brewer with similar transitions Subscribe online at http://inside. Dave Knachel hokiesports.com or cut out this Photographer Compliance | 12 section and mail with a check for the appropriate amount. Makes a Academic Spotlight – Courtney Stutts | 14 great gift for every Hokie! Stacey Wells Women’s soccer player seeks career as Designer financial planner 1 Print options Academic Spotlight – Juan Campos | 15 1-year: $37.95 2-year: $69.95 Contributors Terry Bolt - Hokie Club Track runner plans on career in civil engineering Please make checks payable to: -

Alma Mater Dynasty Football League Draft Results 22-Feb-2008 05:45 PM Eastern

www.rtsports.com Alma Mater Dynasty Football League Draft Results 22-Feb-2008 05:45 PM Eastern Alma Mater Dynasty Football League Draft Mon., Apr 30 2007 5:29:00 AM Rounds: 7 Round 1 Round 4 #1 TurkeyFoot Rams - Adrian Peterson, RB, MIN #1 TurkeyFoot Rams - Dwayne Wright, RB, BUF #2 Huron Tigers - Calvin Johnson, WR, DET #2 Lee's Summit Tigers - Buster Davis, LB, DET #3 Lee's Summit Tigers - Marshawn Lynch, RB, BUF #3 Leto Falcons - Anthony Spencer, LB, DAL #4 Creston Polar Bears - Dwayne Jarrett, WR, CAR #4 Creston Polar Bears - Zach Miller, TE, OAK #5 Struthers Puledros - Robert Meachem, WR, NOR #5 Oak Grove Panthers - Adam Carriker, DL, STL #6 E. P. Red Raiders - Steve Smith, WR, NYG #6 Vincennes Lincoln Alices - Jacoby Jones, WR, HOU #7 Cedaredge Bruins - Brandon Jackson, RB, GNB #7 Cedaredge Bruins - Johnnie Lee Higgins, WR, OAK #8 Leto Falcons - Brady Quinn, QB, CLE #8 Cathedral Golden Gales - Anthony Waters, LB, SDG #9 Oak Ridge Eagles - JaMarcus Russell, QB, OAK #9 Oak Ridge Eagles - Eric Weddle, DB, SDG #10 Central Wildcats - Anthony Gonzalez, WR, IND #10 Central Wildcats - Antonio Pittman, RB, STL #11 Lee's Summit Tigers - Patrick Willis, LB, SFO #11 Cathedral Golden Gales - Michael Griffin, DB, TEN #12 E. P. Red Raiders - Lorenzo Booker, RB, MIA #12 E. P. Red Raiders - Quincy Black, LB, TAM #13 TurkeyFoot Rams - Sidney Rice, WR, MIN #13 Highland Park Giants - Garrett Wolfe, RB, CHI #14 Oak Grove Panthers - Kevin Kolb, QB, PHI #14 Oak Grove Panthers - Mike Walker, WR, JAC Round 2 Round 5 #1 TurkeyFoot Rams - John Beck, QB, MIA #1 TurkeyFoot Rams - Aaron Ross, DB, NYG #2 Leto Falcons - Dwayne Bowe, WR, KAN #2 Vincennes Lincoln Alices - Aundrae Allison, WR, MIN #3 E. -

Cornhuskers Hokies

Virginia Tech vs. Nebraska • Page 1 Nebraska Saturday, Sept. 27, 2008 CORNHUSKERS Kickoff: 8 PM 3-0, 0-0 Big 12 Memorial Stadium/Osborne Field (81,067) Virginia Tech Lincoln, Neb. HOKIES Series vs. NU: NU leads, 1-0 3-1, 2-0 ACC Series Streak: NU, one 1994, when the former Big Eight Conference THE CHECKLIST merged with four Texas schools that had been members of the Southwest Conference, which ✓ Nebraska holds a 1-0 lead in the series had just disbanded. with the lone meeting coming in 1996. • This will be the farthest west, ✓ Tech has never played a football game in longitudinally, Tech has traveled for a regular the state of Nebraska. season game since playing at Oklahoma’s ✓ This will be the farthest west the Hokies Memorial Stadium in 1991 (-97.442511). Tech have played a regular season game since played at Texas A&M’s Kyle Field (-96.34192) playing at Oklahoma in 1991. in 2002. Nebraska’s Osborne Field sits at ✓ Since 1946, Virginia Tech football teams -96.705639, just west of College Station, Texas. have a 77-62-1 record in night games, including a 44-29-1 record under coach FAMILIAR WITH THE PELINIS Frank Beamer. • While this may be Bo Pelini’s first year as ✓ The Hokies are 16-35 all-time in football the head coach of the Cornhuskers, both he and games played in the Central Time Zone. his brother, Carl, have some experience against the Hokies. Bo was the defensive coordinator at BROADCAST INFORMATION LSU the past three seasons and faced Tech last year at home, helping lead the Tigers to a 48-7 TV Information: The game will be televised THE SERIES victory. -

Wotzpwwanugtf6z6prky.Pdf

2010 - GAME TWO VS. PATRIOTS - 4:15 P.M. ET - CBS NEW YORK JETS (1-0) VS. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (1-0) SUN., SEPT. 19 - NEW MEADOWLANDS STADIUM (82,500) HEADLINES PATRIOTS/JETS AT A GLANCE • Jets face division rival, New England Patriots. The two Series: 99th meeting, Jets lead series 50-48-1 teams have split the series in each of the last two sea- Last Meeting: Patriots 31, Jets 14, Gillette Stadium, sons. This marks the third consecutive season the two 11/22/09 teams have met in the second week of the season, both times the games were played in New Jersey. Last Jets Win: Jets 16, Patriots 9, Meadowlands, 9/20/09 • Jets defense held a Ravens offense that averaged 137.5 Notable: The Jets are 29-22 overall at home and 2-1 in yards per game in 2009 to 49 yards on 35 carries (1.4 overtime games in the series versus the Patriots. avg.). Series Highlights: In November 2008, the Jets and Patriots • P Steve Weatherford recorded a net punting average of played in a classic overtime game. The Jets jumped out to 44.8 yards on six punts. He placed four punts inside the a 24-6 lead in the first half, but the Patriots roared back in Ravens 20-yard line. the second to send the game into overtime. After winning the coin toss, the Jets elected to go on offense. After a sack and BROADCAST COVERAGE an incomplete pass, Jets QB Brett Favre found TE Dustin TELEVISION: CBS Keller for a 16-yard completion for a first down and from Play-by-play: Jim Nantz Analysts: Phil Simms there drove down to the Patriots 16. -

Green Bay Enters the Draft with Nine Selections

Packers Public Relations l Lambeau Field Atrium l 1265 Lombardi Avenue l Green Bay, WI 54304 l 920/569-7500 l 920/569-7201 fax Jason Wahlers, Aaron Popkey, Sarah Quick, Tom Fanning, Nate LoCascio, Katie Hermsen VOL. XVIII; NO. 1 2016 NFL DRAFT PREVIEW GREEN BAY ENTERS THE DRAFT WITH NINE SELECTIONS a second-round pick and two third-round choices to New England for This weekend, the Green Bay Packers will welcome another rookie class the opportunity to draft Matthews plus a fifth-round pick, the Southern to their roster through the NFL Draft, held April 28-30 at the Auditorium California linebacker has proven to be well worth it, earning six selec- Theatre of Roosevelt University in Chicago. tions to the Pro Bowl in his first seven years. u Armed with seven of their own selections – plus two u In 2010, Green Bay selected T Bryan Bulaga in the first round at No. compensatory picks – the Packers will have plenty of 23. He started 33 games from 2010-12 and 27 of 32 over the last two opportunities to add more talent and depth to their seasons after missing 2013 due to injury. Thompson moved up in the roster. All picks are eligible to be traded except for third round to select S Morgan Burnett (No. 71 overall), who has the compensatory choices. started 71 contests over the past five seasons. u Green Bay enters the draft with a pick in every round, u Seven of the 10 players in the 2011 draft class went on to appear in a including three selections in the fourth round. -

BILL WALSH NFL DIVERSITY COACHING FELLOWSHIP STRENGTHENS PIPELINE for FUTURE COACHES Diversity Team Personnel Fellowship Program Continues in 32Nd Year

BILL WALSH NFL DIVERSITY COACHING FELLOWSHIP STRENGTHENS PIPELINE FOR FUTURE COACHES Diversity team personnel fellowship program continues in 32nd year NEW YORK (November 12, 2019) – As part of its continuing efforts to strengthen the NFL coaching pipeline, the NFL today announced that 179 coaches participated in the 2019 BILL WALSH NFL DIVERSITY COACHING FELLOWSHIP. Of the total, 53 Bill Walsh fellows are former NFL players. The Bill Walsh NFL Diversity Coaching Fellowship, named after late Pro Football Hall of Fame head coach Bill Walsh, provides NFL coaching experience to talented minority college coaches, high school coaches and former players. Walsh introduced the concept to the league in 1987 when he brought a group of minority coaches into his San Francisco 49ers’ training camp. “The Bill Walsh Diversity Coaching Fellowship is a tremendous opportunity for rising coaches to hone their skills by experiencing first-hand the methods and philosophies of NFL coaching staffs,” said NFL Executive Vice President of Football Operations TROY VINCENT. “This fellowship is key to the future of the game as it identifies the next generation talented coaches.” Since inception, nearly 2,000 minority coaches have participated in the program with support from all 32 clubs during offseason workouts, minicamps, and training camp. Some fellows were extended through the 2019 season such as NFL Legend HINES WARD who in September joined the New York Jets staff as a full-time offensive assistant. Other clubs who extended fellowships through the season include Atlanta Falcons, Buffalo Bills, Cleveland Browns, Denver Broncos, Indianapolis Colts, Jacksonville Jaguars, Los Angeles Rams, and the Washington Redskins. -

New York Jets

New York Jets hen Rex Ryan stepped up to the podium on De- son, the Colts dominated the Jets in the first half of W cember 20 and conceded the Jets’ chances of their Week 16 encounter; the 9-3 score belied the fact making the playoffs, it appeared that that he and his that the Colts had seen wide-open receivers drop two team had been victimized by bad luck. The Jets had touchdown passes. The Jets returned the second half just lost a 10-7 heartbreaker to the Falcons, thanks kickoff for a touchdown, giving them a shock lead, but to three failed field after the Colts equal- goals and three picks ized, the starters came from rookie quarter- JETS SUMMARY out. Indy capitulated, back Mark Sanchez. It and the Jets took advan- 2009 Record: 9-7 marked their fifth loss tage of Curtis Painter to in games decided by Pythagorean Wins: 11.4 (6th) earn the win. less than a touchdown. DVOA: 16.9% (9th) A week later, the Jets A team with the vaunted and Bengals went into combination required to Offense: -9.0% (22nd) their flexed Sunday win close, meaningful Defense: -23.4% (1st) night matchup knowing games — a great de- Special Teams: 2.5% (6th) that a Jets win would fense and strong ground ensure a rematch be- game — had failed to Variance: 21.5% (27th) tween the two teams a win in exactly those 2009: Fifteen weeks of bad luck followed by four weeks of week later. The Ben- sort of games. Colum- good luck.