Management of Bleeding Associated with Malignant Wounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WO 2016/133483 Al 25 August 2016 (25.08.2016) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2016/133483 Al 25 August 2016 (25.08.2016) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: SHENIA, Iaroslav Viktorovych [UA/UA]; Feodosiyskyy A61L 15/44 (2006.01) A61L 26/00 (2006.01) lane, 14-a, kv. 65, Kyiv, 03028 (UA). A61L 15/54 (2006.01) (74) Agent: BRAGARNYK, Oleksandr Mykolayovych; str. (21) International Application Number: Lomonosova, 60/5-43, Kyiv, 03189 (UA). PCT/UA20 16/0000 19 (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (22) International Filing Date: kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, 15 February 2016 (15.02.2016) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, (25) Filing Language: English DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (26) Publication Language: English HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, (30) Priority Data: MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, a 2015 01285 16 February 2015 (16.02.2015) UA PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, u 2015 01288 16 February 2015 (16.02.2015) UA SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, (72) Inventors; and TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

Dietary Supplements Compendium Volume 1

2015 Dietary Supplements Compendium DSC Volume 1 General Notices and Requirements USP–NF General Chapters USP–NF Dietary Supplement Monographs USP–NF Excipient Monographs FCC General Provisions FCC Monographs FCC Identity Standards FCC Appendices Reagents, Indicators, and Solutions Reference Tables DSC217M_DSCVol1_Title_2015-01_V3.indd 1 2/2/15 12:18 PM 2 Notice and Warning Concerning U.S. Patent or Trademark Rights The inclusion in the USP Dietary Supplements Compendium of a monograph on any dietary supplement in respect to which patent or trademark rights may exist shall not be deemed, and is not intended as, a grant of, or authority to exercise, any right or privilege protected by such patent or trademark. All such rights and privileges are vested in the patent or trademark owner, and no other person may exercise the same without express permission, authority, or license secured from such patent or trademark owner. Concerning Use of the USP Dietary Supplements Compendium Attention is called to the fact that USP Dietary Supplements Compendium text is fully copyrighted. Authors and others wishing to use portions of the text should request permission to do so from the Legal Department of the United States Pharmacopeial Convention. Copyright © 2015 The United States Pharmacopeial Convention ISBN: 978-1-936424-41-2 12601 Twinbrook Parkway, Rockville, MD 20852 All rights reserved. DSC Contents iii Contents USP Dietary Supplements Compendium Volume 1 Volume 2 Members . v. Preface . v Mission and Preface . 1 Dietary Supplements Admission Evaluations . 1. General Notices and Requirements . 9 USP Dietary Supplement Verification Program . .205 USP–NF General Chapters . 25 Dietary Supplements Regulatory USP–NF Dietary Supplement Monographs . -

Therapeutic Options to Minimize Allogeneic Blood

Santos AA, etREVIEW al. - Therapeutic ARTICLE options to minimize allogeneic blood Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc 2014;29(4):606-21 transfusions and their adverse effects in cardiac surgery: A systematic review Therapeutic options to minimize allogeneic blood transfusions and their adverse effects in cardiac surgery: A systematic review Opções terapêuticas para minimizar transfusões de sangue alogênico e seus efeitos adversos em cirurgia cardíaca: Revisão sistemática Antônio Alceu dos Santos1, MD; José Pedro da Silva1, MD, PhD; Luciana da Fonseca da Silva1, MD, PhD; Alexandre Gonçalves de Sousa1, MD; Raquel Ferrari Piotto1, MD, PhD; José Francisco Baumgratz1, MD DOI: 10.5935/1678-9741.20140114 RBCCV 44205-1596 Abstract Results: Treating anemia and thrombocytopenia, suspending Introduction: Allogeneic blood is an exhaustible therapeutic anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents, reducing routine phle- resource. New evidence indicates that blood consumption is ex- botomies, utilizing less traumatic surgical techniques with moderate cessive and that donations have decreased, resulting in reduced hypothermia and hypotension, meticulous hemostasis, use of topical blood supplies worldwide. Blood transfusions are associated and systemic hemostatic agents, acute normovolemic hemodilu- with increased morbidity and mortality, as well as higher hos- tion, cell salvage, anemia tolerance (supplementary oxygen and pital costs. This makes it necessary to seek out new treatment normothermia), as well as various other therapeutic options have options. Such options -

Alphabetical Listing of ATC Drugs & Codes

Alphabetical Listing of ATC drugs & codes. Introduction This file is an alphabetical listing of ATC codes as supplied to us in November 1999. It is supplied free as a service to those who care about good medicine use by mSupply support. To get an overview of the ATC system, use the “ATC categories.pdf” document also alvailable from www.msupply.org.nz Thanks to the WHO collaborating centre for Drug Statistics & Methodology, Norway, for supplying the raw data. I have intentionally supplied these files as PDFs so that they are not quite so easily manipulated and redistributed. I am told there is no copyright on the files, but it still seems polite to ask before using other people’s work, so please contact <[email protected]> for permission before asking us for text files. mSupply support also distributes mSupply software for inventory control, which has an inbuilt system for reporting on medicine usage using the ATC system You can download a full working version from www.msupply.org.nz Craig Drown, mSupply Support <[email protected]> April 2000 A (2-benzhydryloxyethyl)diethyl-methylammonium iodide A03AB16 0.3 g O 2-(4-chlorphenoxy)-ethanol D01AE06 4-dimethylaminophenol V03AB27 Abciximab B01AC13 25 mg P Absorbable gelatin sponge B02BC01 Acadesine C01EB13 Acamprosate V03AA03 2 g O Acarbose A10BF01 0.3 g O Acebutolol C07AB04 0.4 g O,P Acebutolol and thiazides C07BB04 Aceclidine S01EB08 Aceclidine, combinations S01EB58 Aceclofenac M01AB16 0.2 g O Acefylline piperazine R03DA09 Acemetacin M01AB11 Acenocoumarol B01AA07 5 mg O Acepromazine N05AA04 -

Formulary April

Standard Formulary MedPerform Medium April, 2021 Copyright © 2020 MedImpact Healthcare Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. This document is confidential and proprietary to MedImpact and contains material MedImpact may consider Trade Secrets. This document is intended for specified use by Business Partners of MedImpact under permission by MedImpact and may not otherwise be used, reproduced, transmitted, published, or disclosed to others without prior written authorization. MedImpact maintains the sole and exclusive ownership, right, title, and interest in and to this document. MedPerform Medium Formulary What is the standard formulary? The MedImpact formulary is a list of covered drugs selected by physician and pharmacist subject matter experts who collaboratively support MedImpact’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee. The plan will cover drugs listed in the formulary as long as the drug is indicated for the clinical condition, is prescribed in the appropriate manner, the prescription is filled at a participating network pharmacy, and other plan rules are followed. For more information on how to fill your prescriptions, please review your Evidence of Coverage. Can the Formulary (drug list) change? Drugs may be added or deleted from the formulary during the year. If a drug is removed from the formulary, [or] adds prior authorization, quantity limits and/or step therapy restrictions on a drug or moves a drug to a higher cost-sharing tier], the plan will notify affected members of the change before the change becomes effective. If the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) deems a drug on the formulary to be unsafe or the drug’s manufacturer removes the drug from the market, the plan will immediately remove the drug from the formulary. -

Guidelines on the Management of Bleeding for Palliative Care Patients with Cancer

Yorkshire Palliative Medicine Clinical Guidelines Group Guidelines on the management of bleeding for palliative care patients with cancer November 2008 Authors: Dr Bill Hulme and Dr Sarah Wilcox, on behalf of the Yorkshire Palliative Medicine Clinical Guidelines Group. Overall objective : To provide evidence-based guidance for the management of bleeding in cancer patients within specialist palliative care. Search strategy: Medline, CINAHL and Embase databases were searched with the help of an experienced librarian using MESH terms for cancer, neoplasm, the generic and trade names for individual drugs and haemorrhage or site-specific areas for haemorrhage. Searches were limited to papers published in English relating to human adults up until March 2008. References obtained were hand searched for additional materials relevant to this review. Additional searches were also conducted for NICE and SIGN guidelines, Cochrane databases, Clinical Knowledge Summaries and publications from associated Royal Colleges. The bulletin board of palliativedrugs.com and palliative medicine textbooks were also reviewed for expert advice. Level of evidence: Evidence regarding medications included in this review has been graded according to criteria described by Keeley [2003] on behalf of the SIGN research group (see appendix 4). Review date: September 2013 Competing interests: None declared Disclaimer: These guidelines are the property of the Yorkshire Palliative Medicine Clinical Guidelines Group and are intended for qualified, specialist palliative medicine professionals as an information resource. They should be used in the clinical context of each individual patient’s needs and reference to appropriate prescribing texts / literature should also be made. The Clinical Guidelines Group takes no responsibility for any consequences of any actions taken as a result of using these guidelines. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,050,265 B2 Jamis0n Et Al

US009050265B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,050,265 B2 Jamis0n et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jun. 9, 2015 (54) VITAMIN CAND VITAMINK, AND (56) References Cited COMPOSITIONS THEREOF FOR TREATMENT OF OSTEOLYSIS OR U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS PROLONGATION OF PROSTHETIC 6,468.414 B1 10/2002 Mahdavi et al. IMPLANT 6,599.945 B2 7/2003 Docherty et al. 7,091,241 B2 8, 2006 Gilloteaux et al. (75) Inventors: James M. Jamison, Stow, OH (US); 2002fO1464637,094.809 A1B2 10,8, 20062002 phyDocherty et al. Thomas M. Miller, El Cajon, CA (US); 2003/0073738 A1 4/2003 Gilloteaux et al. Deborah R. Neal, Uniontown, OH (US); 2007/0043.11.0 A1 2/2007 Gilloteaux et al. Mark Willam Kovacik, Mogadore, OH 2008/0081041 A1 4/2008 Nemeth (US); Michael John Askew, 39S A1 33.9 Miller SA Strongsville, OH (US); Richard Albert 2011/0028436 A1 2/2011 Greenwa Mostardi, Ravenna, OH (US) 2011 0160301 A1 6, 2011 Tsai et al. FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (73) Assignee: Summa Health System, Akron, OH (US) CN 101537174 9, 2009 JP 2006131611 A 5, 2006 WO O247493 A2 6, 2002 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this WO 2007 147128 A2 12/2007 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 WO 2009 118726 A2 10, 2009 (21) Appl. No.: 13/384,574 Bullough, “Metallosis.” J. Joint Bone Surg. Br., 1994, 76, 687-688. Rae, “The toxicity of metals used in orthopaedic prostheses. An experimental study using cultured human synovial fibroblasts.” J. (22) PCT Filed: Jul.19, 2010 Joint Bone Surg. -

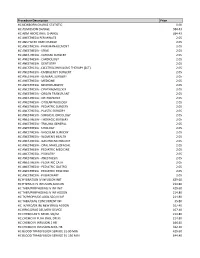

Procedure Description Price HC NEWBORN CHARGE STATISTIC

Procedure Description Price HC NEWBORN CHARGE STATISTIC 0.00 HC ADMISSION CHARGE 584.43 HC ADM HSCRC RATE CHANGE 584.43 HC ANESTHESIA PER MINUTE 2.05 HC ANS HSCRC RATE CHANGE 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - PAIN MANAGEMENT 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - SPINE 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - CARDIAC SURGERY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - CARDIOLOGY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - DENTISTRY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY (ECT) 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - EMERGENCY SURGERY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - GENERAL SURGERY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - MEDICINE 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - NEUROSURGERY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - OPHTHALMOLOGY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - ORGAN TRANSPLANT 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - ORTHOPEDICS 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - OTOLARYNGOLOGY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - PEDIATRIC SURGERY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - PLASTIC SURGERY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - SURGICAL ONCOLOGY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - THORACIC SURGERY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - TRAUMA GENERAL 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - UROLOGY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - VASCULAR SURGERY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - WOMEN'S HEALTH 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - GASTROENTEROLOGY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - ORAL MAXILLOFACIAL 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - PEDIATRIC MEDICINE 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - PODIATRY 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - ANESTHESIA 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - PEDIATRIC CATH 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - PEDIATRIC GASTRO 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - PEDIATRIC HEM ONC 2.05 HC ANESTHESIA - PULMONARY 2.05 HC HYDRATION IV INFUSION INIT 429.60 HC HYDRATE IV INFUSION ADD-ON 214.80 HC THER/PROPH/DIAG IV INF INIT 429.60 HC THER/PROPH/DIAG IV INF ADDON 214.80 HC TX/PROPH/DG ADDL SEQ IV INF 214.80 HC THER/DIAG CONCURRENT INF 35.80 HC TX/PRO/DX INJ NEW DRUG ADDON 107.40 HC IRRIG -

Topical Delivery of Alpha1-Antichymotrypsin for Wound

Topical delivery of α1-Antichymotrypsin for wound healing Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Fakultät für Chemie und Pharmazie der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München vorgelegt von Roland Schmidt aus Treuchtlingen München 2005 Erklärung Diese Dissertation wurde im Sinne von § 13 Abs. 3 und 4 der Promotionsordnung vom 29. Januar 1998 von Herrn Prof. Dr. G. Winter betreut. Ehrenwörtliche Versicherung Diese Dissertation wurde selbständig, ohne unerlaubte Hilfe erarbeitet. München, 01. Januar 2005 (Roland Schmidt) Dissertation eingereicht am: 10. Januar 2005 1. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. G. Winter 2. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. W. Frieß Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 1. Februar 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Foremost, I wish to express my deepest appreciation to my supervisor, Prof. Dr. Gerhard Winter. I am much obliged to him for his professional guidance and his scientific support. On a personal note, I especially want to thank him for inspiring my interest in protein pharmaceuticals, for teaching me so much, and for creation of an outstanding working climate. I am also grateful to the Switch Biotech AG, Neuried, Germany for financial support. I would like to acknowledge Dr. Uwe Goßlar for rendering every assistance and the always professional and personally warm contact. Moreover, I would like to thank Annette, Björn, and especially Olivia for performing the Bioassays. Thanks are also extended to Prof. Dr. Bracher, Prof. Dr. Frieß, PD Dr. Paintner, Prof. Dr. Schlitzer, and Prof. Dr. Wagner for serving as members of my thesis advisor committee. I very much enjoyed working at the Department for Pharmaceutical Technology and Biopharmaceutics of the Munich Ludwig-Maximilians-University, what was mainly due to the cooperative and most convenient atmosphere. -

WO 2016/069458 Al 6 May 2016 (06.05.2016) W P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2016/069458 Al 6 May 2016 (06.05.2016) W P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/122 (2006.01) A61P 1/18 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A61K 31/375 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, (21) Number: International Application DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/US2015/057336 HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, (22) International Filing Date: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, 26 October 2015 (26.10.201 5) MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, (25) Filing Language: English SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, (26) Publication Language: English TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 62/069,156 27 October 2014 (27. 10.2014) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, (71) Applicant: SUMMA HEALTH SYSTEM [US/US]; 525 TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, E. -

Ohsu Health Services Formulary

OHSU HEALTH SERVICES FORMULARY Effective January 1, 2020 LAST UPDATED: September 27, 2021 Introduction The formulary is a list of drugs that are covered. The list is from a healthcare team that makes sure drugs are safe and effective. We update the formulary at least once a year. We will tell you about changes that affect you at least 30 days ahead of time. How to search You can look for drugs on the formulary in a couple of ways: By Use: Drugs used for the same medical reason are listed together. For example, drugs used to treat infections are listed under “Antibiotics.” Alphabetically: Drugs are also listed in alphabetical order with page number. Limits and restrictions Drugs that have limits or need more information before they are covered, are listed in these ways: Type Description Your provider will need to fill out a form and send it to us so Prior Approval (PA) we can review if the drug is covered Step Therapy (ST) You may need to first try another drug or series of drugs Quantity Limit (QL) A limited amount of drug is covered without our approval These drugs are covered only for certain ages. If you are Age Limit (AL1) younger or older than the age listed, we will need more information from your provider before we will cover the drug Specialty Drug (S) You will need to fill the drug at a specialty pharmacy Drugs not covered Drugs that are not covered include the following: Drugs not on the formulary Drugs not used for approved medical reasons Drugs used for conditions not covered by the Oregon Health Plan Drugs used for research Drugs used for cosmetic reasons Mental health drugs are not listed on the formulary, but are covered by the Oregon Health Authority drug program.