Regional Strategy Paper and Regional Indicative Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Southwest Pacific: U.S

Order Code RL34086 The Southwest Pacific: U.S. Interests and China’s Growing Influence July 6, 2007 Thomas Lum Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Bruce Vaughn Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division The Southwest Pacific: U.S. Interests and China’s Growing Influence Summary This report focuses on the 14 sovereign nations of the Southwest Pacific, or Pacific Islands region, and the major external powers (the United States, Australia, New Zealand, France, Japan, and China). It provides an explanation of the region’s main geographical, political, and economic characteristics and discusses United States interests in the Pacific and the increased influence of China, which has become a growing force in the region. The report describes policy options as considered at the Pacific Islands Conference of Leaders, held in Washington, DC, in March 2007. Although small in total population (approximately 8 million) and relatively low in economic development, the Southwest Pacific is strategically important. The United States plays an overarching security role in the region, but it is not the only provider of security, nor the principal source of foreign aid. It has relied upon Australia and New Zealand to help promote development and maintain political stability in the region. Key components of U.S. engagement in the Pacific include its territories (Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa), the Freely Associated States (Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau), military bases on Guam and Kwajalein atoll (Marshall Islands), and relatively limited aid and economic programs. Some experts argue that U.S. involvement in the Southwest Pacific has waned since the end of the Cold War, leaving a power vacuum, and that the United States should pay greater attention to the region and its problems. -

Country Report September 2003

Country Report September 2003 Samoa September 2003 The Economist Intelligence Unit 15 Regent St, London SW1Y 4LR United Kingdom The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit is a specialist publisher serving companies establishing and managing operations across national borders. For over 50 years it has been a source of information on business developments, economic and political trends, government regulations and corporate practice worldwide. The Economist Intelligence Unit delivers its information in four ways: through its digital portfolio, where the latest analysis is updated daily; through printed subscription products ranging from newsletters to annual reference works; through research reports; and by organising seminars and presentations. The firm is a member of The Economist Group. London New York Hong Kong The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit 15 Regent St The Economist Building 60/F, Central Plaza London 111 West 57th Street 18 Harbour Road SW1Y 4LR New York Wanchai United Kingdom NY 10019, US Hong Kong Tel: (44.20) 7830 1007 Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Tel: (852) 2585 3888 Fax: (44.20) 7830 1023 Fax: (1.212) 586 0248 Fax: (852) 2802 7638 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.eiu.com Electronic delivery This publication can be viewed by subscribing online at www.store.eiu.com Reports are also available in various other electronic formats, such as CD-ROM, Lotus Notes, online databases and as direct feeds to corporate intranets. For further information, please contact your nearest Economist Intelligence Unit office Copyright © 2003 The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. -

The Transilient Fiji- Indian Diaspora Engagement and Assimilation in Transnational Space

Transnational Indian Diaspora Engagement and development: The transilient Fiji- Indian diaspora engagement and assimilation in transnational space Manoranjan Mohanty The University of the South Pacific, Fiji Abstract The Indian immigrants or ‘girmitiyas’ under British indenture labour system have gradually transformed to Indian Diaspora in transnational space be it from Mauritius, British Guiana, Trinidad, South Africa, Fiji, Jamaica or Suriname. The onset of globalization has stimulated the contemporary diasporic movements and social and economic networking and in turn, a greater diasporic engagement... Cheaper means of communication and growth of mass media and ICT, have contributed much to diaspora movement across border, creating ‘transnational communities’, globally. Today, the diaspora has been emerged as a new resource and an agent of change and development. It has been a major source of remittance, investment, and human and social capital and has been emerging as an alternative development strategy. The role of diaspora in contemporary development of both country of origin and country of residence draws greater attention today than ever before. The ‘girmitiyas’ in Fiji that arrived between 1879-1916 have undergone generational changes, and gradually transformed to distinct Fijian-Indian Diaspora within Fiji and abroad. These ‘transient’ and ‘translient’ migrants, through a ‘double’ and ‘triple’ chain- migration have formed distinct transnational Fijian-Indian diaspora especially in the Pacific- Rim metropolitan countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and USA. They are deeply engaged in social, cultural and economic development and assimilated in transnational space. Bollywood films have helped binding Indian diaspora especially Fiji- Indians abroad who have maintained Indian cultural identity in the global space. -

The Case of the Fiji Islands

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 12-13-2011 Explaining Investment Policies in Microstates: The Case of the Fiji Islands Sudarsan Kant University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Kant, Sudarsan, "Explaining Investment Policies in Microstates: The Case of the Fiji Islands" (2011). Dissertations. 395. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/395 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Explaining Investment Policies in Microstates: The Case of the Fiji Islands By Sudarsan Kant A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Missouri-St. Louis In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In Political Science November 15, 2011 Advisory Committee Kenneth Thomas, PhD., (Chair) Nancy Kinney, Ph.D. Eduardo Silva, Ph.D. Daniel Hellinger, Ph.D. Abstract . Prevailing theories have failed to take into account the development of policy and institutions in microstates that are engineered to attract investments in areas of comparative advantage as these small islands confront the challenges of globalization and instead have emphasized migration, remittances and foreign aid (MIRAB) as an explanation for the survival of microstates in the global economy. This dissertation challenges the MIRAB model as an adequate explanation of investment strategy in microstates and argues that comparative advantage is a better theory to explain policy behavior of microstates. -

Joint Media Release

Joint Media Release Pacific welcomes Prime Minister Key’s Future of Fisheries funding boost For immediate release: Friday 9th September 2016 FSMPIF2016, Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia – A funding injection announced today by the Prime Minister of New Zealand, John Key, in Pohnpei will provide a significant boost for the regional Roadmap aimed at ensuring sustainable development in Pacific fisheries. Visiting Micronesia for the Pacific Forum Leaders Meeting, Prime Minister Key has announced NZ $12.15 million to support sustainable coastal fisheries and aquaculture in the region. The Pacific Community through its Coastal and Oceanic Fisheries Programs will partner with the Forum Fisheries Agency and New Zealand to implement the two new initiatives. The five-year "Improving fisheries food security and sustainable livelihoods for Pacific Island communities" project will focus on improving fisheries governance in nations across the Pacific. “The contribution of New Zealand and Australia enables Pacific nations to step up action on the commitments and goals set by Pacific leaders; for their oceanic and coastal fisheries,” says FFA Director General James Movick. At the 46th Forum, New Zealand committed $50m NZD to support fisheries management, and the work involved is well underway. The new NZ$4.9 million Sustainable Pacific Aquaculture Development project will focus on sustainable aquaculture demonstrating enhanced business acumen, reduced aquatic biosecurity risks and increased uptake of improved aquaculture practices. In welcoming the announcement by Prime Minister Key, the Pacific Community Director-General, Dr Colin Tukuitonga, said the scale of the projects will make it possible to address the complex issues affecting food security in isolated island communities. -

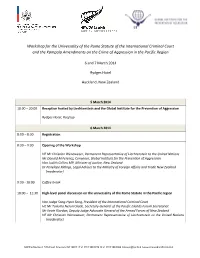

2014-02-27 ICC Workshop Programme

Workshop for the Universality of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court and the Kampala Amendments on the Crime of Aggression in the Pacific Region 6 and 7 March 2014 Rydges Hotel Auckland, New Zealand 5 March 2014 18:00 – 20:00 Reception hosted by Liechtenstein and the Global Institute for the Prevention of Aggression Rydges Hotel, Rooftop 6 March 2014 8:00 – 8:30 Registration 8:30 – 9:30 Opening of the Workshop HE Mr Christian Wenaweser, Permanent Representative of Liechtenstein to the United Nations Mr Donald M Ferencz, Convenor, Global Institute for the Prevention of Aggression Hon Judith Collins MP, Minister of Justice, New Zealand Dr Penelope Ridings, Legal Adviser to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade New Zealand (moderator) 9:30 - 10:00 Coffee break 10:00 – 11:30 High-level panel discussion on the universality of the Rome Statute in the Pacific region Hon Judge Sang-Hyun Song, President of the International Criminal Court HE Mr Tuiloma Neroni Slade, Secretary-General of the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat Mr Kevin Riordan, Deputy Judge Advocate General of the Armed Forces of New Zealand HE Mr Christian Wenaweser, Permanent Representative of Liechtenstein to the United Nations (moderator) 633 Third Avenue | 27th Floor| New York| NY 10017 | T +1 (212) 599 0220 | F +1 (212) 599 0064 | [email protected] | www.newyork.liechtenstein.li 2 11:30 – 13:00 The Rome Statute and its relevance to the Pacific region Hon Ross Robertson, MP, President of Parliamentarians for Global Action Prof Roger Clark, Rutgers University -

Australia, the Southwest Pacific, and United States Interests

Order Code RL32187 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Australia, the Southwest Pacific, and United States Interests January 7, 2004 name redacted and name redacted Analysts in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Australia, the Southwest Pacific, and United States Interests Summary The major U.S. interests in the Southwest Pacific are preventing the rise of terrorist threats, working with and maintaining the region’s U.S. territories, commonwealths, and military bases (American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the Reagan Missile Test Site on Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands), and enhancing U.S.-Australian cooperation in pursuing mutual political, economic, and strategic objectives in the area. The United States and Australia share common interests in countering transnational crime and preventing the infiltration of terrorist organizations in the Southwest Pacific, hedging against the growing influence of China, and promoting political stability and economic development. The United States has supported Australia’s increasingly proactive stance and troop deployment in Pacific Island nations torn by political and civil strife such as East Timor, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. Australia may play a greater strategic role in the region as the United States seeks to redeploy its Asia-Pacific force structure. This report will be updated as needed. Contents U.S. Interests in the Southwest Pacific .................................1 The Evolving U.S.-Australian Strategic Relationship......................2 Australia’s Role in the Region........................................5 China’s Growing Regional Influence...................................6 List of Figures Figure 1. Map of the Southwest Pacific ................................7 Australia, the Southwest Pacific, and United States Interests U.S. -

FAO/FFA REGIONAL WORKSHOP to PROMOTE the FULL and EFFECTIVE IMPLEMENTATION of PORT STATE MEASURES to COMBAT IUU FISHING 28 Augus

FAO/FFA REGIONAL WORKSHOP TO PROMOTE THE FULL AND EFFECTIVE IMPLEMENTATION OF PORT STATE MEASURES TO COMBAT IUU FISHING 28 August – 1 September 2006 Mocambo Hotel Nadi, Fiji WORKSHOP PROSPECTUS 1. INTRODUCTION Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing occurs in all capture fisheries and poses a direct and significant threat to effective conservation and management of many fish stocks. By frustrating fishery management objectives, IUU fishing can lead to the collapse of a fishery or seriously impair efforts to rebuild depleted fish stocks. This in turn may result in lost economic and social opportunities, both short-term and long-term, and may diminish food security. Left unchecked, IUU fishing can completely negate the benefits of effective fisheries management. Since the late 1990s, a number of international fora have issued calls to combat IUU fishing,1 and in March 2001, the FAO Committee on Fisheries (COFI) adopted the International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate IUU fishing (IPOA-IUU), which had been concluded within the framework of the 1995 FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (“Code of Conduct”). In November, 2001, the United Nations General Assembly urged all States, as a matter of priority, to coordinate their activities and cooperate directly and, as appropriate, through relevant regional fisheries management organizations, in the implementation of the IPOA-IUU and to develop corresponding national plans of action (NPOAs).2 Since then, the IPOA-IUU has been the subject of ongoing high-level attention. To support implementation, the FAO has prepared and published Technical Guidelines3 and mounted a series of six regional workshops between 2003 and 2005 to build human capacity in developing countries for the elaboration of national plans of action to combat IUU fishing (NPOAs-IUU).4 Evaluations of the workshops by participants were very positive, and many called for related follow-up activities. -

Shaping New Regionalism in the Pacific Islands: Back to the Future?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Chand, Satish Working Paper Shaping New Regionalism in the Pacific Islands: Back to the Future? ADB Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration, No. 61 Provided in Cooperation with: Asian Development Bank (ADB), Manila Suggested Citation: Chand, Satish (2010) : Shaping New Regionalism in the Pacific Islands: Back to the Future?, ADB Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration, No. 61, Asian Development Bank (ADB), Manila, http://hdl.handle.net/11540/1941 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/109573 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo www.econstor.eu ADB Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration Shaping New Regionalism in the Pacific Islands: Back to the Future? Satish Chand No. -

Oecd/Undesa/Unescap Workshop on Developing Sustainability Strategies in Asia

DRAFT AGENDA OECD/UNDESA/UNESCAP WORKSHOP ON DEVELOPING SUSTAINABILITY STRATEGIES IN ASIA UN Conference Centre, Bangkok, Thailand, 8-9 March 2007 Purpose: This workshop will review national sustainable development strategies (NSDS) in countries in Asia and the Pacific and their relationship to national development plans and poverty reduction strategies (PRS) with a view to better integration. It is co-sponsored by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the United Nations Division for Sustainable Development (UNDESA) and the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP). Thursday, 8 March 2007 9h00 – 10h00 Opening Remarks • Kim Hak-Su, Executive Secretary, UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) • Kiyo Akasaka, Deputy Secretary-General, OECD • JoAnne DiSano, Director, UN Division for Sustainable Development (UNDESA) 10h00 – 11h00 Session 1: Sustainability and Development in Asia and the Pacific Overview: Rae Kwon Chung, Director, Environment and Sustainable Development Division, UNESCAP Discussants: • Bertrand Fort, Coordinator, Asia Europe Environment Forum (ASEF) • Jan Adams, Australian Ambassador for Environment, Asia Pacific Economic Co-operation (APEC) 11h00 – 11h30 Coffee 11h30 – 13h00 • Greg Urwin, Secretary General, Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS) • Chong Chun Kim, Director General, Presidential Commission on Sustainable Development, Republic of Korea General Discussion 13h00 – 14h30 Lunch Keynote Speaker -- Emil Salim, Chair, Preparatory Committee, World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) 1 14h30 – 16h00 Session 2: Governance Approaches to National Sustainable Development Strategies in Asia and the Pacific Overview: Representative, UNEP Regional Resource Centre for Asia and the Pacific Discussants: • Magarita Roque Songco, Deputy Director General, National Economic and Development Authority, Philippines • B. -

Why Don't Pacific Island Countries' Economies Grow Faster.Pdf

Pacific Interactions Pasifika in New Zealand – New Zealand in Pasifika Edited by Alastair Bisley Institute of Policy Studies Published in 2008 (online only) http://ips.ac.nz Institute of Policy Studies School of Government Victoria University of Wellington PO Box 600 Wellington © Institute of Policy Studies ISBN 978-1-877347-27-6 IPS/Pub/159 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without the permission of the Institute of Policy Studies. Copy editor: Belinda Hill Cover design: Alltex Design Contents List of Figures...............................................................................................................iv List of Maps...................................................................................................................v List of Tables.................................................................................................................v List of Boxes.............................................................................................................. viii Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................ix Introduction –Alastair Bisley.........................................................................................1 1 Emerging Demographic and Socioeconomic Features of the Pacific Population in New Zealand – Paul Callister and Robert Didham ....................13 2 Pacific -

BACKGROUND Existing Cooperation Possible Areas of Collaboration

5th Meeting of the Commission Adelaide, Australia, 18 to 22 January 2017 COMM 5 - DOC-05 rev.1 (23.12.2016) Options for Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) with other RFMOs Secretariat BACKGROUND At its last meeting in January 2016, the SPRFMO Commission has asked the Secretariat to assess and advise the Commission on options for Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) with neighbouring or overlapping RFMOs. Such MoUs are intended to facilitate the cooperation between organisations. Existing Cooperation SPRFMO has an “Arrangement” with CCAMLR (ANNEX 4) as well as a MoU between the SPRFMO and ACAP Secretariats (ANNEX 5). It is noteworthy that ACAP contributed extensive expert advice to the development of CMM 4.09 (Minimising Bycatch of Seabirds). In addition, there exists an informal collaboration among all Secretariats of RFMOs, through (a) the Regional Bodies Secretariat’s Network (RSN) (described in ANNEX 1) convened every two years in conjunction with FAO’s Committee on Fisheries (COFI), and (b) intersessional communications and consultations. Since the last Commission meeting, the Executive Secretary has consulted with the Secretaries of neighbouring and overlapping RFMOs (see report in ANNEX 2) and found that all are interested in strengthening the informal collaboration and possibly broadening and formalising it through MoUs. Summary descriptions of advisory RFBs of possible interest to SPRFMO and operating in the Pacific and some global relevant organisations are given in ANNEX 3. Possible areas of collaboration The general scope of collaboration with other RFMOs will be similar and might include the following areas: Matters related to IUU fishing, e.g. recognition of each other’s IUU Lists Monitoring and surveillance including vessel information, VMS, and observers, e.g.