Are Cigarettes Defective in Design?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Votes Cast

w Facebook.com/ Twitter.com Volume 59, No. 107 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2013 BrooklynEagle.com BrooklynEagle @BklynEagle 50¢ BROOKLYN SUNY Campuses TODAY Primary EPT Receive Grades S . 11 State University of New Good morning. Today is York (SUNY) Chancellor the 254th day of the year. It Nancy L. Zimpher on Tues- Votes is the anniversary of the day commended 36 SUNY Sept. 11, 2001, “Attack on campuses on being recog- America,” when terrorist nized as “military friendly” members of Al Qaeda hi- by a top-rated national mil- Cast jacked four jet planes. They itary publication, G.I. Jobs PROBLEMS Magazine, and more than crashed two of the planes with the city’s into the World Trade Cen- 20 campuses were ranked ter and one into the Penta- among the nation’s top col- old-style lever gon (the fourth plane leges and universities by voting machines crashed in Pennsylvania U.S. News & World Report. that were after passengers attempted “SUNY is a leader in as- brought out to overcome the hijackers), sisting military personnel again for this killing more than 2,900 in the transition to civilian life after their service to our year’s primary people. Several Brooklyn were seen across firehouses, most notably country, and we take great the Middagh Street fire- pride in providing New the borough on house in Brooklyn Heights, York’s returning service Tuesday. This the Red Hook firehouse and men and women with high- photo was taken Squad One in Park Slope, er education,” said Zim- in Crown were devastated after many pher. -

BDE 05-13-14.Indd

A Special Section of BROOKLYN EAGLE Publications 6 Cool Things Happening IN BROOKLYN 1 2 3 4 5 6 Check out brooklyneagle.com • brooklynstreetbeat.com • mybrooklyncalendar.com Week of May 15-21, 2014 • INBrooklyn - A special section of Brooklyn Eagle/BE Extra/Brooklyn Heights Press/Brooklyn Record • 1INB EYE ON REAL ESTATE Victorian Flatbush Real Estate, Installment One Mary Kay Gallagher Reigns—and Alexandra Reddish Rocks, Too Bring Big Bucks If You Want to Buy— Home Prices Are Topping $2 Million By Lore Croghan INBrooklyn She’s the queen of Vic- torian Flatbush real estate, with nearly a half-century of home sales under her belt. Her granddaughter, who got her real estate license at age 18, is no slouch either. Mary Kay Gallagher, age 94, sells historic homes in y Prospect Park South, Ditmas Park, Midwood and nearby areas—stunning, stand-alone single-family properties that are a century old or more, with verdant lawns and trees. Ninety percent of them have driveways, which of course are coveted in Brooklyn. Granddaughter Alexan- dra Reddish, 40, is Gallagh- er’s savvy colleague in home sales at Mary Kay Gallagh- er Real Estate. A daughter- in-law, Madeleine Gallagh- er, handles rentals and helps with sales. Hello, Gorgeous! Welcome to Victorian Flatbush. Eagle photos by Lore Croghan “We keep it in the fami- ly,” Mary Kay Gallagher said. landmarked Ditmas Park that The map on Gallagher’s who’ve sold their townhous- She launched her bro- needs a lot of work. It went website—marykayg.com/ es for $3 million to $4 mil- ker career in 1970 after the for $1.42 million in March. -

Queens Today

Vol. 66, No. 228 MONDAY, MARCH 15, 2021 50¢ QUEENS All four Queens congresswomen call on Gov. Cuomo to resign By David Brand TODAY Queens Daily Eagle Queens’ four female congressmembers FebruaryAUGUSTMARCH 15, 10,6, 20212020 2020 called on Gov. Andrew Cuomo to resign Fri- day in a series of statements released in co- ordination with other members of New York LITTLE NECK RESTAURANT IL BAC- City’s House delegation. co has dropped their lawsuit against the city after U.S. Reps. Grace Meng, Carolyn Malo- Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced indoor dining ney, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Nydia would be expanded to 50 percent this week. The Velazquez each issued statements urging Cuo- restaurant filed the suit in August, claiming that mo to step down amid numerous accusations the limitations impacted business as diners ate of sexual misconduct and harassment. Cuomo inside in nearby Nassau County. is also facing intense scrutiny for concealing nursing home death totals. THE MAYOR’S OFFICE OF MEDIA “The mounting sexual harassment allega- and Entertainment and NYC Department of tions against Governor Cuomo are alarming,” Meng said. “The challenges facing our state and Education put out a call for DOE student film- QUEENS New Yorkers are unprecedented, and I believe makers interested in conducting interviews as he is unable to govern effectively. The Gover- part of the 3rd Annual New York City Public nor should resign for the good of our state.” School Film Festival, scheduled for May 6. U.S. Sens. Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gil- Students in middle and high school can submit librand, New York City representatives Jerrold their short films to the festival until March 16. -

Dems Unite After Thompson Withdraws SEPT

w Facebook.com/ Twitter.com Volume 59, No. 110 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2013 BrooklynEagle.com BrooklynEagle @BklynEagle 50¢ BROOKLYN TODAY Dems Unite After Thompson Withdraws SEPT. 17 By Jennifer Peltz Associated Press Good morning. Today After mayoral candidate is the 260th day of the year. and lifelong Brooklyn resident Police brutality is far from a Bill Thompson conceded the new issue: The Brooklyn Democratic primary race to Daily Eagle of Sept. 17, front-runner Bill de Blasio on 1878, reported on charges Monday, Democrats said they against Police Officer would focus on defeating Joe Murtha (no first name Lhota at the polls in November. given) of “using his [night] Thompson endorsed de Bla- stick too freely.” Apparently, sio at City Hall, saying he was a drunken boy was wander- proud to support him as the party’s nominee. ing around when Officer “Bill de Blasio and I want to Murtha decided to take him move the city forward,” into custody. At that mo- Thompson said. “This is bigger ment, the boy’s sister ar- than any one of us.” rived and offered to take the The potential runoff had boy home. Officer Murtha’s loomed as another act in the De- response was to give both of mocratic drama over choosing a them “a violent blow with successor to three-term Mayor his club.” Michael Bloomberg — a fight Well-known people who that would keep Democrats tilt- were born today include for- ing at each other while Republi- mer basketball coach Phil cans and independents looked Jackson, comedienne Rita ahead to the general election. -

Bay Ridge 'Princess'

VOLUME 67 NUMBER 34 • SEPTEMBER 6-12, 2019 Community News Beacon in South Brooklyn Since 1953 Where’s My Bus? MTA removes schedules from stops PAGE 2 WHAT’S NEWS Photo courtesy of Kids of the Arts Productions GRID-LOCK SLAMMED In the wake of a moratorium by National Grid on installing new gas hookups in Brooklyn, Queens and Long Island, New York State might consider ending a long-standing agreement it has with the company, giving it a monopoly on supplying gas to homes and businesses. Gov. Andrew Cuomo has directed the Department of Public Service to broad- en an investigation it is currently conducting into the moratorium and to consider alternatives to National Grid as a franchisee for some or all of the areas it currently serves if the problem is not resolved. For more on this story, go to page 10. IMPEACHMENT-KEEN Demonstrators held a protest rally outside U.S. Rep. Max Rose’s Bay Ridge office late last month to urge the pol to back the impeachment of President Donald Trump. Rose, who won his seat in 2018 and has earned a reputation as a centrist willing to work across the aisle on certain issues, has steadfastly refused to back impeachment. For more on this story, go to brooklynreporter.com. FOODIE OUTPOST OPENS Sahadi’s, the family specialty grocery store that’s been a Brooklyn fixture since 1948, finally opened its doors in Industry City late last month. The new space is 7,500 square feet with approximately 80 seats and a bar. It offers the traditional ancient grains and spices, bins of freshly roasted nuts, dried fruits, imported olives and old-fashioned barrels of coffee beans that customers look for at its first location on Atlantic Avenue, along with new additions, such as light breakfast, full coffee service and lunch. -

Remembering the Battle of Brooklyn

Two Sections w Facebook.com/ Twitter.com Volume 59, No. 90 FRIDAY, AUGUST 16, 2013 BrooklynEagle.com BrooklynEagle @BklynEagle 50¢ BROOKLYN Coney Amusement TODAY Remembering AUG. 16 Ride Injures Boy A 5-year-old boy suf- Good morning. Today is fered lacerations to his The Battle of the 228th day of the year. The left leg and head after Brooklyn Daily Eagle of Aug. 16, 1901, took note of the large falling off a kiddie ride at number of poolrooms existing an amusement park in Brooklyn within a few blocks of Borough Brooklyn, police said Hall. At that time, “poolrooms” Wednesday. BATTLE OF BROOKLYN WEEK meant places, usually saloons, Police are investigat- will take place from Aug. 18 where bets were placed on the ing how the boy, who is to 25, and events (including horses. Playing billiards was re-enactments such as the just one of the ways patrons re- expected to survive, was laxed until their results came in able to get out of the Sea one seen here) are planned from the track. By the beginning Serpent Roller Coaster at at Green-wood Cemetery, of World War I, however, Deno’s Wonder Wheel the Old Stone House, Brook- “pool” increasingly referred to Amusement Park in lyn Bridge Park and Fort the game of billiards itself. Coney Island. Well-known people who Greene Park. The Battle of were born today include actress The boy, whose name Brooklyn, which was the first Angela Bassett (“Waiting to Ex- was not released, was battle of the Revolutionary taken to Bellevue Hospi- hale,” “Malcolm X”), sports- War after the Declaration, caster and Hall of Fame foot- tal, where officials said he ball player Frank Gifford, TV was in stable condition. -

The Great Transformation: Exploring Jamaica Bay in the Late 19Th and Early 20Th Centuries Through Newspaper Accounts

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The Great Transformation Exploring Jamaica Bay in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries Through Newspaper Accounts Natural Resource Report NPS/NCBN/NRR—2018/1607 ON THIS PAGE Top image: Haunts of Jamaica Bay Fishermen (source: Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 25 August 1895), Bottom image: How They Tracked Down the Typhoid Oysters (source: The Salt Lake Tribune, 13 February 1913). ON THE COVER Cover image: Sea Side House, Second Landing, Rockaway Beach, Long Island, as viewed from bay side (source: Ephemeral New York, https://ephemeralnewyork.wordpress.com, circa 1900) The Great Transformation Exploring Jamaica Bay in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries Through Newspaper Accounts Natural Resource Report NPS/NCBN/NRR—2018/1607 John Waldman Queens College The City University of New York 65-30 Kissena Blvd Flushing, NY 11367 William Solecki Hunter College The City University of New York 695 Park Ave, New York, NY 10065 March 2018 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Newspaper 2,052,430

Line Ads NEWSPAPER 2,052,430 820,972 25 Word Line Ad 1x $499 Newspaper advertising is incredibly cost effective and can reach almost any demographic and specific target audience. 2x $399 We represent over 300 daily and weekly community publications and websites in New York, and itʼs our job to make your advertising as easy and effective as possible. 3x $349 53 PARTICIPATING NEWSPAPERS 4x $289 BRONX COUNTY NEW YORK COUNTY QUEENS COUNTY Queens Community News Bronx Community News Chelsea Clinton News Bayside Times Queens Courier Bronx Free Press Chelsea News Caribbean Life — RidgewoodTimes/Times Bronx Times Reporter Chelsea Now Queens/Bronx/Manhattan .....Newsweekly and Bronx Times Desi Talk Queens Chronicle — Rockaway Journal The Riverdale Press Downtown Express Central Queens Edition The Courier Sun Additional Words Gay City News Queens Chronicle — The Flushing Times KINGS COUNTY Gujarat Times Eastern Queens Edition TimesLedger $10 each Bay News Haiti Liberte Queens Chronicle — Brooklyn Community News Harlem Commuity News Mid Queens Edition Brooklyn Eagle Impacto Latin News Queens Chronicle — Brooklyn Graphic Manhattan Times Northeast Queens Edition Brooklyn Spectator New York Amsterdam News Queens Chronicle — Caribbean Life-Brooklyn Zone New York Beacon Northern Queens Edition Main Basin Courier News India-Times Queens Chronicle — Our Time Press Our Town Downtown South Queens Edition Park Slope Courier Our Town (NYC) Queens Chronicle — The Jewish Press The Villager (NYC) Southeast Queens Edition The Tablet The Villager Express Queens Chronicle — The West Side Spirit Western Queens Edition The Westsider Call us today and let’s get started! New York Press Service 518-464-6483 NYNEWSPAPERS.COM PS The Newspaper Advertising Network guarantees 90% placement of all ads in its participating newspapers. -

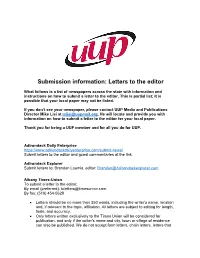

Submission Information: Letters to the Editor

Submission information: Letters to the editor What follows is a list of newspapers across the state with information and instructions on how to submit a letter to the editor. This is partial list; it is possible that your local paper may not be listed. If you don’t see your newspaper, please contact UUP Media and Publications Director Mike Lisi at [email protected]. He will locate and provide you with information on how to submit a letter to the editor for your local paper. Thank you for being a UUP member and for all you do for UUP. Adirondack Daily Enterprise https://www.adirondackdailyenterprise.com/submit-news/ Submit letters to the editor and guest commentaries at the link. Adirondack Explorer Submit letters to: Brandon Loomis, editor: [email protected] Albany Times-Union To submit a letter to the editor: By email (preferred): [email protected] By fax: (518) 454-5628 Letters should be no more than 250 words, including the writer’s name, location and, if relevant to the topic, affiliation. All letters are subject to editing for length, taste, and accuracy. Only letters written exclusively to the Times Union will be considered for publication, and only if the writer's name and city, town or village of residence can also be published. We do not accept form letters, chain letters, letters that have been posted on websites, or letters that have been prepared by anyone other than the individual who has signed it. Letters must include the writer's name, address and daytime phone number so that we can contact you to verify the letter (we will not publish your street address and phone number, only your name and the community in which you live). -

Guide to the Postcard File Ca 1890-Present (Bulk 1900-1940) PR54

Guide to the Postcard File ca 1890-present (Bulk 1900-1940) PR54 The New-York Historical Society 170 Central Park West New York, NY 10024 Descriptive Summary Title: Postcard File Dates: ca 1890-present (bulk 1900-1940) Abstract: The Postcard File contains approximately 61,400 postcards depicting geographic views (New York City and elsewhere), buildings, historical scenes, modes of transportation, holiday greeting and other subjects. Quantity: 52.6 linear feet (97 boxes) Call Phrase: PR 54 Note: This is a PDF version of a legacy finding aid that has not been updated recently and is provided “as is.” It is key-word searchable and can be used to identify and request materials through our online request system (AEON). 2 The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections PR 054 POSTCARD FILE ca. 1890-present (bulk dates: 1900-1940) 52.6 lin. ft., 97 boxes Series I. Geographic Locations: United States Series II. Geographic Locations: International Series III. Subjects Processed by Jennifer Lewis January 2002 PR 054 3 Provenance The Postcard File contains cards from a variety of sources. Larger contributions include 3,340 postcard views of New York City donated by Samuel V. Hoffman in 1941 and approximately 10,000 postcards obtained from the stock file of the Brooklyn-based Albertype Company in 1953. Access The collection open to qualified researchers. Portions of the collection that have been photocopied or microfilmed will be brought to the researcher in that format; microfilm can be made available through Interlibrary Loan. Photocopying Photocopying will be undertaken by staff only, and is limited to twenty exposures of stable, unbound material per day. -

Newspapers by County | New York Press Association

Newspapers by County | New York Press Association http://nynewspapers.com/newspapers-by-county/ Contact Us Become a member Calendar NYPA Board of Directors Contact Us(518) 464-6483 search Home Advertising » Member Services » Newsletters » Contest & Events » Resources » Newspapers by County A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A 1 of 28 8/31/17, 6:51 AM Newspapers by County | New York Press Association http://nynewspapers.com/newspapers-by-county/ Albany Altamont Enterprise and Albany 4345Thursday County Post, The Business Review (Albany), The 6,071Friday Capital District Mature Life 20,000Monthly Capital District Parent 35,000Monthly Capital District Parent Pages 20,000Monthly Capital District Senior Spotlight 18,000Monthly Colonie-Loudonville Spotlight 2885Wednesday Colonie-Delmar-Slingerlands 20213Bi-Thursday Pennysaver Evangelist, The 35,828Thursday Latham Pennysaver 15,861Thursday News-Herald, The 423Thursday Spotlight (Delmar), The 5,824Wednesday Times Union 56,493Daily Allegany Alfred Sun 878Thursday Patriot and Free Press 3,331Wednesday Wellsville Daily Reporter 4,500Tues-Fri B Bennington, VT Northshire Free Press 7,600Friday Bronx Bronx Community News 5,000Thursday Bronx Free Press 17,300Wednesday Bronx News 4,848Thursday Bronx Penny Pincher 78,400 Bronx Penny Pincher (Castle Hill 16,050Thursday Edition), The Bronx Penny Pincher (Morris Park 16,200Thursday Edition), The Bronx Penny Pincher (Parkchester 8,050Thursday Edition), The Bronx Penny Pincher (Pelham Parkway 15,000Thursday North), The Bronx Penny Pincher (Throggs -

STATED MEETING of Wednesday, October 31, 2018, 2:00 P.M

October 31, 2018 THE COUNCIL Minutes of the Proceedings for the STATED MEETING of Wednesday, October 31, 2018, 2:00 p.m. The Public Advocate (Ms. James) Acting President Pro Tempore and Presiding Officer Council Members Corey D. Johnson, Speaker Adrienne E. Adams Vanessa L. Gibson Bill Perkins Alicia Ampry-Samuel Mark Gjonaj Keith Powers Diana Ayala Barry S. Grodenchik Antonio Reynoso Inez D. Barron Robert F. Holden Donovan J. Richards Joseph C. Borelli Ben Kallos Carlina Rivera Justin L. Brannan Andy L. King Ydanis A. Rodriguez Fernando Cabrera Peter A. Koo Deborah L. Rose Margaret S. Chin Karen Koslowitz Helen K. Rosenthal Andrew Cohen Rory I. Lancman Rafael Salamanca, Jr Costa G. Constantinides Bradford S. Lander Ritchie J. Torres Robert E. Cornegy, Jr Stephen T. Levin Mark Treyger Laurie A. Cumbo Mark D. Levine Eric A. Ulrich Chaim M. Deutsch Alan N. Maisel Paul A. Vallone Ruben Diaz, Sr. Steven Matteo James G. Van Bramer Daniel Dromm Carlos Menchaca Jumaane D. Williams Rafael L. Espinal, Jr I. Daneek Miller Kalman Yeger Mathieu Eugene Francisco P. Moya The Public Advocate (Ms. James) assumed the chair as the Acting President Pro Tempore and Presiding Officer for these proceedings. After consulting with the City Clerk and Clerk of the Council (Mr. McSweeney), the presence of a quorum was announced by the Public Advocate (Ms. James). 3918 October 31, 2018 There were 51 Council Members marked present at this Stated Meeting held in the Council Chambers of City Hall, New York, N.Y. INVOCATION The Invocation was delivered by Rabbi Michael S. Miller, Executive Vice President and CEO of the Jewish Community Relations Council of New York, 225 West 34th Street, Suite 1607, New York, N.Y.