The Building of a Wall of Separation Between New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let Me Distill What Rosemary Ruether Presents As the Critical Features Of

A Study of the Rev. Naim Ateek’s Theological Writings on the Israel-Palestinian Conflict The faithful Jew and Christian regularly turn to the texts of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament for wisdom, guidance, and inspiration in order to understand and respond to the world around them. Verses from the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament are regularly employed in the discussion of the Israel-Palestine conflict. While the inspiration for justice and righteousness on behalf of all who are suffering is a hallmark of both scriptures, the present circumstance in the Land of Israel poses unique degrees of difficulty for the application of Biblical text. The prophets of old speak eternal and absolute ideas, in the circumstance and the vernacular of their time. God speaks. Men and women hear. The message is precise. The challenge of course is to extract the idea and to apply it to the contemporary circumstance. The contemporary State of Israel is not ancient Israel of the First Temple period, 11th century BCE to 6th century BCE, nor Judea of the first century. Though there are important historical, national, familial, faith, and communal continuities. In the absence of an explicit word of God to a prophet in the form of prophecy we can never be secure in our sense that we are assessing the contemporary situation as the ancient scriptural authors, and, more importantly, God, in Whose name they speak, would have us do. If one applies to the State of Israel biblical oracles addressed to the ancient people Israel, one has to be careful to do so with a sense of symmetry. -

The Jew of Celsus and Adversus Judaeos Literature

ZAC 2017; 21(2): 201–242 James N. Carleton Paget* The Jew of Celsus and adversus Judaeos literature DOI 10.1515/zac-2017-0015 Abstract: The appearance in Celsus’ work, The True Word, of a Jew who speaks out against Jesus and his followers, has elicited much discussion, not least con- cerning the genuineness of this character. Celsus’ decision to exploit Jewish opinion about Jesus for polemical purposes is a novum in extant pagan litera- ture about Christianity (as is The True Word itself), and that and other observa- tions can be used to support the authenticity of Celsus’ Jew. Interestingly, the ad hominem nature of his attack upon Jesus is not directly reflected in the Christian adversus Judaeos literature, which concerns itself mainly with scripture (in this respect exclusively with what Christians called the Old Testament), a subject only superficially touched upon by Celsus’ Jew, who is concerned mainly to attack aspects of Jesus’ life. Why might this be the case? Various theories are discussed, and a plea made to remember the importance of what might be termed coun- ter-narrative arguments (as opposed to arguments from scripture), and by exten- sion the importance of Celsus’ Jew, in any consideration of the history of ancient Jewish-Christian disputation. Keywords: Celsus, Polemics, Jew 1 Introduction It seems that from not long after it was written, probably some time in the late 240s,1 Origen’s Contra Celsum was popular among a number of Christians. Eusebius of Caesarea, or possibly another Eusebius,2 speaks warmly of it in his response to Hierocles’ anti-Christian work the Philalethes or Lover of Truth as pro- 1 For the date of Contra Celsum see Henry Chadwick, introduction to idem, ed. -

© Cambridge University Press Cambridge

Cambridge University Press 0521826926 - A Dictionary of Jewish-Christian Relations Edited by Edward Kessler and Neil Wenborn Excerpt More information AAAA Aaron Aaron, as a point of contact between Jews and Aaron is a figure represented in both Testaments Christians, was acknowledged in the Letter to and referred to typologically in both. His priestly the Hebrews as the founder of the Jewish priest- role is the dominant feature shared by Judaism and hood, who offered acceptable sacrifice to God. Christianity, but in the latter this role is appropri- The anonymous author appropriated the still- ated in order to highlight the superiority of the developing Jewish tradition and contrasts the once- priesthood of Jesus. Thereafter, because the Jewish and-for-all priesthood of Jesus (which was claimed tradition continued to stress his priestly status, he to derive from the priesthood of Melchizedek) with faded out of the Christian tradition. the inferior yet legitimate priesthood of Aaron. In the book of Exodus Aaron appears as the There is no polemic intent against Aaron in brother of Moses and Miriam, playing a subordi- Hebrews. Two texts, Ps. 2.7 and 110.4, are used to nate but important role as spokesperson for Moses show that God designated Jesus as the unique Son before the Pharaoh, although in the earliest literary and High Priest. His self-sacrifice, analogous to the strata of the Torah there is no evidence that he is sacrifice of the High Priest on the Day of Atone- a priest. His priestly role becomes clear only in the ment,isdepictedasacovenant-inauguratingevent, later so-called Priestly Document, in the descrip- fulfilling the expectations of the new covenant in tion of the construction of the Tabernacle and the Jeremiah. -

Tertullian's Adversus Judaeos

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Theology Graduate Theses Theology Spring 2013 Tertullian’s Adversus Judaeos: a Tale of Two Treatises John P. Fulton Providence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/theology_graduate_theses Part of the Religion Commons Fulton, John P., "Tertullian’s Adversus Judaeos: a Tale of Two Treatises" (2013). Theology Graduate Theses. 3. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/theology_graduate_theses/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theology at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TERTULLIAN’S ADVERSUS JUDAEOS: A TALE OF TWO TREATISES THESIS Submitted to Providence College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by John Peter Fulton Approved by: Director Reader Reader Date August 26, 2011 PROVIDENCE COLLEGE TERTULLIAN’S ADVERSUS JUDAEOS: A TALE OF TWO TREATISES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY BY JOHN PETER FULTON PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND JULY, 2011 To AFF, TL, CFS, TJW …with deepest gratitude and love. i CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii METHODOLOGICAL NOTES iv INTRODUCTION 1 BACKGROUND 3 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT 6 REFUTATION OF THE UNITY HYPOTHESIS 8 1 ARGUMENT FROM DIFFERENT PURPOSES 8 2 ARGUMENT FROM INDEPENDENCE 12 3 -

Christian Attitudes Toward the Jews in the Earliest Centuries A.D

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 8-2007 Christian Attitudes toward the Jews in the Earliest Centuries A.D. S. Mark Veldt Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the History of Christianity Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Veldt, S. Mark, "Christian Attitudes toward the Jews in the Earliest Centuries A.D." (2007). Dissertations. 925. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/925 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIAN ATTITUDES TOWARD THE JEWS IN THE EARLIEST CENTURIES A.D. by S. Mark Veldt A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Dr. Paul L. Maier, Advisor Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. CHRISTIAN ATTITUDES TOWARD THE JEWS IN THE EARLIEST CENTURIES A.D. S. Mark Veldt, PhD . Western Michigan University, 2007 This dissertation examines the historical development of Christian attitudes toward the Jews up to c. 350 A.D., seeking to explain the origin and significance of the antagonistic stance of Constantine toward the Jews in the fourth century. For purposes of this study, the early Christian sources are divided into four chronological categories: the New Testament documents (c. -

174 Are Other More Detailed Discussions of Epidemics And

174 Book Reviews are other more detailed discussions of epidemics and medical practices. One such example is a post-Jesuit expulsion file, which provides a detailed descrip- tion of the medical responses to a 1780s smallpox outbreak at two missions. Overall, I found this volume to be disappointing. Its narrow bibliographic focus identifies several useful Jesuit medical texts, but there is no discussion of actual medical practices in the field and the effects and effectiveness of Jesuit medicine in the face of serious public health crises. As a bibliographic exercise this volume is also limited. The literature review is overly Eurocen- tric, idiosyncratic, and myopic. Obermeier and the other authors do not cite a number of related and useful studies published outside of Europe. The essays in this volume contribute to our understanding of Jesuit medicine, but in an extremely narrow way. Robert H. Jackson Independent Scholar [email protected] doi:10.1163/22141332-00601012-09 Bruno Feitler The Imaginary Synagogue: Anti-Jewish Literature in the Portuguese Early Modern World (16th–18th Centuries). Leiden: Brill, 2015. Pp. ix + 206. Readers of anti-Judaism/anti-Semitism scholarship know that there is no need of Jews to find Jewish hatred: whether in England after the expulsion of its Jewish population in 1290, or in twentieth-century Japan. According to Jeremy Cohen, medieval Christianity developed a prolific adversus Judaeus literature, which rather antagonized with virtual Judaism than with flesh-and-bones Jews. Not to say that in his Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (Norton, 2014), David Nirenberg claimed that the centrality of this phenomenon in Western cultures stems from a negative idea of Jewishness associated with debased forms of ma- terialism, carnality, and formalistic legalism, including in such domains as the visual arts and music. -

St Paul and the Jews According to St John Chrysostom's Commentary On

St Paul and the Jews According to St John Chrysostom’s Commentary on Romans 9-11 by Fr. Vasile Mihoc University in Sibiu, Romania St John Chrysostom is known not only as the greatest preacher in a Christian pulpit 1, and the most prominent doctor of the Orthodox Church, but also as the preacher of the eight sermons Adversus Judaeos . These discourses were delivered in Antioch in 387, when Chrysostom was a priest 2. In them Chrysostom accumulates against the Jews bitterness, sneers and jibes. Yet, it clearly appears that Chrysostom didn’t have personal relationships with the Jews, as, for example, was the case with Justin the Martyr, Jerome or Augustine. His attack aims stopping his flock’s tendency of sharing in the Jewish festivals, and this tendency says much about the relationships of the two communities in Antioch – unthinkable in later times and maybe difficult for us to understand. 1. The Christian anti-Judaism of the time Starting with the 4 th century speaking against the Jews was ‘fashionable’. ‘The whole Christian literature relating to differences between Jews and Christians – writes Lev Gillet – falls under two possible headings. Such writings belong either to the type Tractatus adversus Judaeos , or to the type Dialogos pros Tryphona 3. They are either polemics against the Jews, 1 His surname ‘Chrysostom’ occurs for the first time in the ‘Constitution’ of pope Vigilius in the year 553 (cf. Migne, P.L. 60, 217). 2 Very probably in the beginning of 381 the bishop Meletius made him deacon, just before his own departure to Constantinople, where he died as president of the Second Ecumenical Council. -

Research.Pdf (755.1Kb)

“FOR GOOD WORK DO THEY WISH TO KILL HIM?”: NARRATIVE CRITIQUE OF THE ACTS OF PILATE A Thesis to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri Columbia, Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by JOHN DAVID SHANNON Dr. Steve Friesen, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2006 © Copyright by John David Shannon, 2006 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction to Topic and Thesis 3 History of the Text Dependence and Independence of Text Section 2: Anti-Semitism and the Acts of Pilate 15 Anti-Semitism in Early Christian Literature The Acts of Pilate Kernels, Satellites, and Plot Summary Section 3: Characters and Evaluative Point of View 28 Annas, Caiaphas, and the Jews Nicodemus: Figure and Jewish Authority Pilate: Outsider and Commentator Joseph of Arimathaea: Insider and Commentator Jesus Phinees, Adas, and Angaeus Other Witnesses Levi Summary Section 4: Conclusion 43 Appendix A: Satellites and Kernels 51 Bibliography 53 1 Section 1: Introduction to Topic and Thesis Generations of scholars have commented on the development of polemics against Jews in early Christian literature. For example, the Gospel of John does not differentiate between various factions among the Jewish assembly, as evident in the first century Gospel of Matthew’s use of titles like scribes and Pharisees, but unifies those opposed to the Christian movement as “Jews.” The trend of vilifying the Jews parallels the growth of second and third century literature exonerating Pontius Pilate and the Roman administration for the death of Jesus and destruction of Jerusalem.1 Again in John, Pilate declares his innocence in Jesus’ death three times and then turns him over to the Jewish assembly to be crucified, not Roman solders as witnessed in Mark, Matthew, and Luke. -

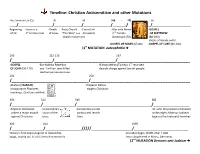

Christian Antisemitism and Other Mutations

Timeline: Christian Antisemitism and other Mutations The Common Era (CE) 30 49 [66 - 70] 85 ___/_______________/____________/____________/______/ ________/_________________ Beginning -Jesus is a -Death -Early Church -Council of -War with Rome. -GOSPEL st nd of CE 1 century Jew of Jesus “The Way” is a Jerusalem 2 Temple OF MATTHEW Jewish movement Destroyed (70) (80-100) (Roots of deicide myth) -GOSPEL OF MARK (65-80) -GOSPEL OF LUKE (80-130) [1st MUTATION Judeophobia 100 132-135 167 /__________________/___________________________/________________________________ -GOSPEL -Bar-Kokhba Rebellion -Bishop Melito (Turkey): 1st recorded OF JOHN (90-120) est. 1 million Jews killed deicide charge against Jewish people Hadrian persecutes Jews 200 250 /__________________________________/____________________________________________ -Mishna (TALMUD) -Emperor Decius incorporates Pharisees targets Christians teachings. Oral law codified. 300 312 315 386 /_____________/______________/_________________________________/________________ -Emperor Diocletian -Constantine’s -Constantine enacts -St. John Chrysostom of Antioch orders a major assault vision of the various anti Jewish writes eight Adversus Judaeos against Christians cross laws (against the Judaizers) homilies 400 414 1095 /______________/________________/////__________________/________________________ History’s first major pogrom in Alexandria, -Crusades begin. (1096: Over 1,000 Egypt, wiping out its city’s Jewish community Jews slaughtered in Mainz, Germany) nd [2 MUTATION Demonic anti-Judaism 1100 1144 1215 1290 /__________/_____________________/______________________________________/_______ st th -1 direct ritual murder -4 Lateran Council: Special clothes/badges for Jews. –Expulsion of Jews of accusation in Norwich, England “There is no salvation outside the Church.” England. First of great European expulsions 1300 1348 1400 1492 /_____________/__________________________/____________/_________________________ “Black Death”: Jews blamed. -

Two Nations in Your Womb: Perceptions of Jews and Christians

1.Yuval,Two Nations in Your Wo 12/7/05 2:58 PM Page 1 one Introduction Et Major Serviet Minori (And the Elder Will Serve the Younger) the thematic framework This book is intended to be a study of the reciprocal attitudes of Jews and Christians toward one another, not a history of the relations between them. I do not intend to present a systematic and comprehensive description of the dialogue and conflicts between Jews and Christians, with their various historical metamorphoses. My sole purpose is to reveal fragmented images of repressed and internalized ideas that lie beneath the surface of the o‹cial, overt religious ideology, which are not always explicitly expressed. My ob- jective is to engage in a rational and open discussion of the roles played by irrationality, disinformation, and misinformation in shaping both the self- definition and the definition of the “other” among Jews and Christians in the Middle Ages. The book revolves around three pairs: Jacob and Esau, Passover and Easter, Jewish martyrdom and blood libel. The first pair is typological, that is, it uses an existing narrative system based on the Scriptures and charges it with the later conflict between Israel and Edom, Judaea and Rome, Judaism and Christianity, a conflict between chosen and rejected, persecuted and perse- cutor. This involvement with the question of who is chosen and who is re- jected, who is “Jacob” and who is “Esau,” reflects a process of self-definition as well as, ipso facto, a definition of the other, the persecutor and rival. The tension evoked by this typology is one between subjugation, suªering, and 1 1.Yuval,Two Nations in Your Wo 12/7/05 2:58 PM Page 2 exile, on the one hand, and dominion, primogeniture, and victory, on the other. -

Comprehending and Confronting Antisemitism an End to Antisemitism!

Comprehending and Confronting Antisemitism An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 1 Comprehending and Confronting Antisemitism A Multi-Faceted Approach Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-063246-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-061859-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-061141-0 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 Licence. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019948124 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing & binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements XI Greetings XXI I Introduction to Combating Antisemitism Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer,Dina Porat, LawrenceH.Schiffman General Introduction “An End to Antisemitism!” 3 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer,Dina Porat, LawrenceH.Schiffman ExecutiveSummary 13 II Leadership Talks Sebastian Kurz Leadership Talk by the Federal Chancellor of the Republic -

Forsaken Or Not? Patristic Argumentation on the Forsakenness of Jews Revisited

Forsaken or Not? Patristic Argumentation on the Forsakenness of Jews Revisited Serafim Seppälä* After the Shoah, the Catholic-Jewish dialogue has reached considerable intellectual depth, existential honesty, theological advancement and thematic width. The Orthodox Church, however, has hardly started its process of reconciliation. At the heart of the problem is the patristic argumentation on the forsakenness of the Jews, which in the Early Church was organically connected with the truth of Christianity. The patristic authors, however, were largely ignorant of the theological developments of Rabbinic Judaism and thus based their reasoning on mistaken presuppositions. In our times, this is especially clear with the patristic argument that it is perpetually impossible for the Jews to return to rule their Holy Land and Jerusalem. Keywords: Judaism, Jews, Jewish, Christian, Orthodox, dialogue, Patristic, ar- gumentation, Holy Land, Jerusalem, Temple, post-Shoah theology, reconciliation. The dialogue of Catholics and Jews has produced some amazing results in last decades, ever since the pioneering document Nostra Aetate (1965).1 In particular, the recent document, “Orthodox Rabbinic statement on Christi- anity” (ORSC)2 is not only ground-breaking but even radical in some of its formulations. Not surprisingly, it has not been accepted by all rabbinic au- thorities (very few statements are), but eighty Orthodox rabbis have indeed signed it, and obviously it has much more support among the more liberal sectors of Judaism. In this paper, I focus on the patristic argumentation related to the most challenging and most difficult aspect of the statement, which basically is about recognition of the positive spiritual status of the other religion.