Triple Ptosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pupillary Disorders LAURA J

13 Pupillary Disorders LAURA J. BALCER Pupillary disorders usually fall into one of three major cat- cortex generally do not affect pupillary size or reactivity. egories: (1) abnormally shaped pupils, (2) abnormal pupillary Efferent parasympathetic fibers, arising from the Edinger– reaction to light, or (3) unequally sized pupils (anisocoria). Westphal nucleus, exit the midbrain within the third nerve Occasionally pupillary abnormalities are isolated findings, (efferent arc). Within the subarachnoid portion of the third but in many cases they are manifestations of more serious nerve, pupillary fibers tend to run on the external surface, intracranial pathology. making them more vulnerable to compression or infiltration The pupillary examination is discussed in detail in and less susceptible to vascular insult. Within the anterior Chapter 2. Pupillary neuroanatomy and physiology are cavernous sinus, the third nerve divides into two portions. reviewed here, and then the various pupillary disorders, The pupillary fibers follow the inferior division into the orbit, grouped roughly into one of the three listed categories, are where they then synapse at the ciliary ganglion, which lies discussed. in the posterior part of the orbit between the optic nerve and lateral rectus muscle (Fig. 13.3). The ciliary ganglion issues postganglionic cholinergic short ciliary nerves, which Neuroanatomy and Physiology initially travel to the globe with the nerve to the inferior oblique muscle, then between the sclera and choroid, to The major functions of the pupil are to vary the quantity of innervate the ciliary body and iris sphincter muscle. Fibers light reaching the retina, to minimize the spherical aberra- to the ciliary body outnumber those to the iris sphincter tions of the peripheral cornea and lens, and to increase the muscle by 30 : 1. -

May Clinical-Sharma (Pdf 143KB)

CLINICAL New-onset ptosis initially diagnosed as conjunctivitis Neil Sharma, Ju-Lee Ooi, Rebecca Davie, Palvi Bhardwaj Case Question 2 divides into superior and inferior branches, Joe, 66 years of age, was referred with What are the causes of an isolated which enter the orbit through the superior a 2-week history of a right upper eyelid oculomotor nerve palsy? orbital fissure. abnormality. He complained of associated The superior division innervates diplopia initially, but this subjectively Question 3 the levator palpebrae superioris and improved after a few days as the eye What clinical features raise the index of superior rectus, while the inferior division became more difficult to open. He had a suspicion of a compressive lesion? mild, intermittent headache for 4 weeks, relieved with oral paracetamol. There Question 4 were no other neurological symptoms. What investigation does this patient He had no other symptoms of giant cell urgently require? arteritis. His past medical history included hypercholesterolaemia for which he was Case continued taking regular statin therapy. He was an Joe was referred for an urgent CT ex-smoker with a 40 pack-year history. angiogram. This showed a large Initially, Joe’s general practitioner (GP) unruptured posterior communicating diagnosed conjunctivitis and prescribed artery aneurysm (Figure 1). He was chloramphenicol drops four times daily. admitted under the neurosurgical team. One week later the symptoms had not improved and Joe was referred to the eye Question 5 Figure 1. 3-dimensional reconstruction image clinic complaining of increasing right What are the surgical options for dealing of the CT-angiogram showing an unruptured periocular pain. -

Albinism Terminology

Albinism Terminology Oculocutaneous Albinism (OCA): Oculocutaneous (pronounced ock-you-low-kew- TAIN-ee-us) Albinism is an inherited genetic condition characterized by the lack of or diminished pigment in the hair, skin, and eyes. Implications of this condition include eye and skin sensitivities to light and visual impairment. Ocular Albinism (OA): Ocular Albinism is an inherited genetic condition, diagnosed predominantly in males, characterized by the lack of pigment in the eyes. Implications of this condition include eye sensitivities to light and visual impairment. Hermansky Pudlak Syndrome (HPS): Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome is a type of albinism which includes a bleeding tendency and lung disease. HPS may also include inflammatory bowel disease or kidney disease. The severity of these problems varies much from person to person, and the condition can be difficult to diagnose with traditional blood tests Chediak Higashi Syndrome: Chediak Higashi Syndrome is a type of albinism in which the immune system is affected. Illnesses and infections are common from infancy and can be severe. Issues also arise with blood clotting and severe bleeding. Melanin: Melanin is pigment found in a group of cells called melanocytes in most organisms. In albinism, the production of melanin is impaired or completely lacking. Nystagmus: Nystagmus is an involuntary movement of the eyes in either a vertical, horizontal, pendular, or circular pattern caused by a problem with the visual pathway from the eye to the brain. As a result, both eyes are unable to hold steady on objects being viewed. Nystagmus may be accompanied by unusual head positions and head nodding in an attempt to compensate for the condition. -

CN Palsy Update for the Primary Care OD 2018

CN Palsy Update for the Primary Care OD 2018 Christopher Wolfe, OD, FAAO, Dipl. ABO Oculomotor Nerve Palsy (CN 3) Signs and Symptoms The primary symptom is diplopia caused by misalignment of the visual axes, the pattern of image separation (horizontal, vertical, oblique) is the key to diagnosing which particular ocular motor cranial nerve (and extraocular muscle) is involved. With a complete unilateral third cranial nerve palsy, the involved eye is deviated "down and out" with partial or complete ptosis. • Pupillary dilatation (involvement) can cause: • Anisocoria (greater in the light) • Symptomatic glare in bright light • Blurred vision for near objects – due to accommodation deficit A painful pupil-involved oculomotor nerve palsy may result from a life-threatening intracranial aneurysm. Prompt diagnosis of an oculomotor nerve palsy is critical to ensure appropriate evaluation and management. Pathophysiology The clinical features of a CN 3 palsy are due to the anatomical relationship of the various branches of the oculomotor nerve and the location of the problem causing the palsy. These anatomical sites can be broken down into: • Nuclear portion: The axons start on each side of the midbrain. Each of the axon origination within the midbrain that travel to a specific extraocular and intraocular muscle can be further classified into a subnucleus. • Fascicular intraparenchymal midbrain portion: This portion of the oculomotor nerve travels courses ventrally (forward) from the nucleus, through the red nucleus, and emerges medially from the cerebral peduncle. • Subarachnoid portion: The nerve then travels in the subarachnoid space anterior to the midbrain and near the posterior communicating artery. An aneurysm at the INTRAOCULAR junction between the posterior communicating artery and INNERVATION the internal carotid artery is one of the critical reasons to differentiate a pupil involved CN 3 palsy. -

Congenital Oculomotor Palsy: Associated Neurological and Ophthalmological Findings

CONGENITAL OCULOMOTOR PALSY: ASSOCIATED NEUROLOGICAL AND OPHTHALMOLOGICAL FINDINGS M. D. TSALOUMAS1 and H. E. WILLSHA W2 Birmingham SUMMARY In our group of patients we found a high incidence Congenital fourth and sixth nerve palsies are rarely of neurological abnormalities, in some cases asso associated with other evidence of neurological ahnor ciated with abnormal findings on CT scanning. mality, but there have been conflicting reports in the Aberrant regeneration, preferential fixation with literature on the associations of congenital third nerve the paretic eye, amblyopia of the non-involved eye palsy. In order to clarify the situation we report a series and asymmetric nystagmus have all been reported as 1 3 7 of 14 consecutive cases presenting to a paediatric associated ophthalmic findings. - , -9 However, we tertiary referral service over the last 12 years. In this describe for the first time a phenomenon of digital lid series of children, 5 had associated neurological elevation to allow fixation with the affected eye. Two abnormalities, lending support to the view that con children demonstrated this phenomenon and in each genital third nerve palsy is commonly a manifestation of case the accompanying neurological defect was widespread neurological damage. We also describe for profound. the first time a phenomenon of digital lid elevation to allow fixation with the affected eye. Two children demonstrated this phenomenon and in each case the PATIENTS AND METHODS accompanying neurological defect was profound. The Fourteen children (8 boys, 6 girls) with a diagnosis of frequency and severity of associated deficits is analysed, congenital oculomotor palsy presented to our paed and the mechanism of fixation with the affected eye is iatric tertiary referral centre over the 12 years from discussed. -

Partial Albinism (Heterochromia Irides) in Black Angus Cattle

Partial Albinism (Heterochromia irides) in Black Angus Cattle C. A. Strasia, Ph.D.1 2 J. L. Johnson, D. V.M., Ph.D.3 D. Cole, D. V.M.4 H. W. Leipold, D.M.V., Ph.D.5 Introduction Various types of albinism have been reported in many Pathological changes in ocular anomalies of incomplete breeds of cattle throughout the world.4 We describe in this albino cattle showed iridal heterochromia grossly. paper a new coat and eye color defect (partial albinism, Histopathological findings of irides showed only the heterochromia irides) in purebred Black Angus cattle. In posterior layer fairly pigmented and usually no pigment in addition, the results of a breeding trial using a homozygous the stroma nor the anterior layer. The ciliary body showed affected bull on normal Hereford cows are reported. reduced amount of pigmentation and absence of corpora Albinism has been described in a number of breeds of nigra. Choroid lacked pigmentation. The Retina showed cattle.1,3-8,12,16,17 An albino herd from Holstein parentage disorganization. Fundus anomalies included colobomata of was described and no pigment was evident in the skin, eyes, varying sizes at the ventral aspect of the optic disc and the horns, and hooves; in addition, the cattle exhibited photo tapetum fibrosum was hypoplastic.12 In albino humans, the phobia. A heifer of black pied parentage exhibited a fundus is depigmented and the choroidal vessels stand out complete lack of pigment in the skin, iris and hair; however, strikingly. Nystagmus, head nodding and impaired vision at sexual maturity some pigment was present and referred to also may occur. -

Wavelength of Light and Photophobia in Inherited Retinal Dystrophy

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Wavelength of light and photophobia in inherited retinal dystrophy Yuki Otsuka1, Akio Oishi1,2*, Manabu Miyata1, Maho Oishi1, Tomoko Hasegawa1, Shogo Numa1, Hanako Ohashi Ikeda1 & Akitaka Tsujikawa1 Inherited retinal dystrophy (IRD) patients often experience photophobia. However, its mechanism has not been elucidated. This study aimed to investigate the main wavelength of light causing photophobia in IRD and diference among patients with diferent phenotypes. Forty-seven retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and 22 cone-rod dystrophy (CRD) patients were prospectively recruited. We designed two tinted glasses: short wavelength fltering (SWF) glasses and middle wavelength fltering (MWF) glasses. We classifed photophobia into three types: (A) white out, (B) bright glare, and (C) ocular pain. Patients were asked to assign scores between one (not at all) and fve (totally applicable) for each symptom with and without glasses. In patients with RP, photophobia was better relieved with SWF glasses {“white out” (p < 0.01) and “ocular pain” (p = 0.013)}. In CRD patients, there was no signifcant diference in the improvement wearing two glasses (p = 0.247–1.0). All RP patients who preferred MWF glasses had Bull’s eye maculopathy. Meanwhile, only 15% of patients who preferred SWF glasses had the fnding (p < 0.001). Photophobia is primarily caused by short wavelength light in many patients with IRD. However, the wavelength responsible for photophobia vary depending on the disease and probably vary according to the pathological condition. Inherited retinal degenerations (IRDs) represent a diverse group of diseases characterized by progressive photo- receptor cell death that can lead to blindness 1. -

Multiple Sclerosis Presenting As Isolated Oculomotor Nerve Palsy Ryan J

THE CANADIAN JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGICAL SCIENCES Multiple Sclerosis Presenting as Isolated Oculomotor Nerve Palsy Ryan J. Uitti and A.H. Rajput ABSTRACT: A 23-year old woman came to the emergency room with an isolated oculomotor nerve palsy (including pupillary dilatation) of rapid onset. Investigations and history revealed no cause. The subsequent course of events indicated a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. While the third nerve has been shown to be involved during the course of multiple sclerosis, this is the first report of a case presenting as an isolated oculomotor nerve paralysis. RESUME: La paralysie isolee du nerf moteur oculaire commun commc manifestation initiale de la sclerose en plaques. Une femme agee de 23 ans se presente a la salle d'urgence avec une paralysie isolee du nerf moteur oculaire commun (incluant une dilatation pupillaire) a debut brusque. L'investigation et l'histoire sont non contributives. L'eVolution subsequente de la maladie r6vele un diagnostic de sclerose en plaques. Meme s'il a ete demontre que le troisieme nerf cranien peut etre atteint a un moment ou l'autre de revolution de la sclerose en plaques, nous rapportons pour la premiere fois un cas dont la manifestation initiale de la maladie est une paralysie isolee du nerf moteur oculaire commun. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 1986; 13:270-272 The onset of multiple sclerosis (MS) is monosymptomatic in gaze was possible. The right pupil was dilated and nonreactive to light approximately 45% of cases.1 When the disease presents as an and accomodation. Optic fundi were normal. A provisional diagnosis of posterior communicating aneurysm was made. -

Pia, Ptosis, and Other Defects of Ocular Movement. Paradoxical

748 CLINICAL NEURO-OPHTHALMOLOGY gia, paralysis of vertical gaze, loss of convergence, exotro- EFFERENT ABNORMALITIES: ANISOCORIA pia, ptosis, and other defects of ocular movement. The presence of anisocoria usually indicates a structural defect of one or both irides or a neural defect of the efferent Paradoxical Reaction of the Pupils to Light and pupillomotor pathways innervating the iris muscles in one Darkness or both eyes. A careful slit-lamp examination to assess the health and integrity of the iris stroma and muscles is an Barricks et al. described three unrelated boys, 2, 6, and important step in the evaluation of anisocoria. If the irides 10 years of age, with congenital stationary night blindness, are intact, then an innervation problem is suspected. As most myopia, and abnormal electroretinograms, who showed a efferent disturbances causing anisocoria are unilateral, two ‘‘paradoxical’’ pupillary constriction in darkness (108). In simple maneuvers are helpful in determining whether it is a lighted room, all three patients had moderately dilated pu- the sympathetic or parasympathetic innervation to the eye pils; however, when the room lights were extinguished, the that is dysfunctional: (1) checking the pupillary light reflex patients’ pupils briskly constricted and then slowly redilated. and (2) measuring the anisocoria in darkness and in bright Subsequent investigators confirmed this observation and re- light. ported similar paradoxical pupillary responses in children When the larger pupil has an obviously impaired reaction and adults with congenital achromatopsia, blue-cone mono- to light stimulation, it is likely the cause of the anisocoria. chromatism, and Leber congenital amaurosis (109,110). In One can presume the problem lies somewhere along the addition, such responses occasionally occur in patients with parasympathetic pathway to the sphincter muscle. -

A Case of Isolated Third Nerve Palsy with Pupillary Involvement Diagnosed with Cavernous Dural Arteriovenous Fistula

CASE REPORT online © ML Comm J Neurocrit Care 2013;6:126-128 ISSN 2005-0348 A Case of Isolated Third Nerve Palsy with Pupillary Involvement Diagnosed with Cavernous Dural Arteriovenous Fistula Yeo Jung Kim, MD, Suk Yoon Lee, MD, Jin-ho Jung, MD, Jung Hwa Seo, MD, Eung-Gyu Kim, MD, PhD, Ki-Hwan Ji, MD, Jong Seok Bae, MD, and Sang-Jin Kim, MD Department of Neurology, Inje University College of Medicine, Busan Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea Background: Third nerve palsy can result from lesions located anywhere along its path from the oculomotor nucleus to the nerve termi- nation within the extraocular muscles of the orbit. Common etiologies of isolated third nerve palsy with pupil involvement are intracranial aneurysm, uncal herniation, neoplasia, and traumatic and inflammatory conditions.Case Report: We present a case of a 71-year-old female with complete left third nerve palsy with pupillary involvement. She was diagnosed with cavernous dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) using source images of time-of-flight (TOF) magnetic resonance (MR). Cerebral angiography revealed a cavernous dAVF via a branch of the distal intracranial artery. Conclusion: Isolated third nerve palsy may be caused by cavernous dAVF, and TOF MR angiog- raphy may be a useful non-invasive pre-diagnostic tool for detecting the shunts. J Neurocrit Care 2013;6:126-128 KEY WORDS: Dural arteriovenous fistula · Third nerve palsy · Magnetic resonance angiography. Introduction The ophthalmological evaluation revealed complete left ptosis and left third nerve palsy with mydriasis without pupil- Isolated third nerve palsy is associated with variable etiol- lary light reflex. The left eye was deviated downward and out- ogies. -

What Is Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome?

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES What is Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome? Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome (HPS) is a rare inherited disease, named after two doctors in Czechoslovakia who, in 1959, recognized similar health conditions in two unrelated adults. Since the discovery of HPS, the condition has occurred all over the world but is most often seen in Puerto Rico. The most common health conditions with HPS are albinism, the tendency to Journal of Hematology bleed easily, and pulmonary fibrosis. A Figure 1. Normal platelet with dense bodies growing number of gene mutations have visualized by electron microscopy. been identified causing HPS (including numbers HPS1 to HPS10). What is albinism? Albinism is an inherited condition in which CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP reduced pigmentation (coloring) is present in the body. As a result, people with albinism are often fair-skinned with light hair. However, skin, hair, and eye color may vary, as some people with albinism may have dark brown hair and green or hazel/brown eyes. Journal of Hematology People with albinism all have low vision and Figure 2. Patient’s platelet with virtually absent dense bodies visualized by electron microscopy. varying degrees of nystagmus. All people who have HPS have albinism, but not all circulate in the blood stream and help the people with albinism have HPS. blood to clot. HPS patients have normal Skin problems—The reduction of numbers of platelets, but they are not pigmentation in the skin from albinism made correctly and do not function well, so results in an increased chance of developing the blood does not clot properly. -

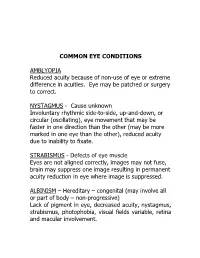

Common Eye Conditions

COMMON EYE CONDITIONS AMBLYOPIA Reduced acuity because of non-use of eye or extreme difference in acuities. Eye may be patched or surgery to correct. NYSTAGMUS - Cause unknown Involuntary rhythmic side-to-side, up-and-down, or circular (oscillating), eye movement that may be faster in one direction than the other (may be more marked in one eye than the other), reduced acuity due to inability to fixate. STRABISMUS - Defects of eye muscle Eyes are not aligned correctly, images may not fuse, brain may suppress one image resulting in permanent acuity reduction in eye where image is suppressed. ALBINISM – Hereditary – congenital (may involve all or part of body – non-progressive) Lack of pigment in eye, decreased acuity, nystagmus, strabismus, photophobia, visual fields variable, retina and macular involvement. ANIRIDIA – Hereditary Underdeveloped or absent iris. Decreased acuity, photophobia, nystagmus, cataracts, under developed retina. Visual fields normal unless glaucoma develops. CATARACTS – Congenital, hereditary, traumatic, disease, or age related (normal part of aging process) Lens opacity (chemical change in lens protein), decreased visual acuity, nystagmus, photophobia (light sensitivity). DIABETIC RETINOPATHY – Pathologic Retinal changes, proliferative – growth of abnormal new blood vessels, hemorrhage, fluctuating visual acuity, loss of color vision, field loss, retinal detachment, total blindness. GLAUCOMA (Congenital or adult) – “SNEAK THIEF OF SIGHT” hereditary, traumatic, surgery High intraocular pressure (above 20-21 mm of mercury) – (in children often accompanied by hazy corneas and large eyes), often due to obstructions that prevent fluid drainage, resulting in damage to optic nerve. Excessive tearing, photophobia, uncontrolled blinking, decreased acuity, constricted fields. HEMIANOPSIA – (Half-vision) optic pathway malfunction pathologic or trauma (brain injury, stroke or tumor) Macular vision may or may not be affected.