Approaches to Capital Financing and Cost Recovery in Sewerage Schemes Implemented in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ward Wise List of Sector Officers, Blos & Blo Supervisors, Municipal

WARD WISE LIST OF SECTOR OFFICERS, BLOS & BLO SUPERVISORS, MUNICIPAL CORPORATION, GURUGRAM Sr. Constit Old P S Ward Sector Officer Mobile No. New Name of B L O Post of B L O Office Address of B L O Mobile No Supervisior Address Mobile No. No. uenc No No. P S No 1 B 15 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 15 Nirmala AWW Pawala Khushrupur 9654643302 Joginder Lect. HIndi GSSS Daultabad 9911861041 (Jahajgarh) 2 B 26 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 26 Roshni AWW Sarai alawardi 9718414718 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 3 B 28 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 28 Anand AWW Choma 9582167811 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 4 B 29 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 29 Rakesh Supervisor XEN Horti. HSVP Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 5 B 30 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 30 Pooja AWW Sarai alawardi 9899040565 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 6 B 31 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 31 Santosh AWW Choma 9211627961 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 7 B 32 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 32 Saravan kumar Patwari SEC -14 -Huda 8901480431 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 8 B 33 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 33 Vineet Kumar JBT GPS Sarai Alawardi 9991284502 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 9 B 34 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 34 Roshni AWW Sarai Alawardi 9718414718 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 10 B 36 1 Sh. -

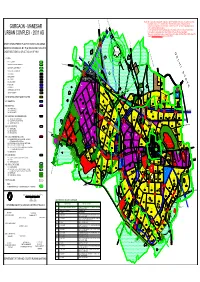

GURGAON - MANESAR on the Website for All Practical Purposes

FROM FARUKHNAGAR FROM FARUKHNAGAR NOTE: This copy is a digitised copy of the original Development Plan notified in the Gazette.Though precaution has been taken to make it error free, however minor errors in the same cannot be completely ruled out. Users are accordingly advised to cross-check the scanned copies of the notified Development plans hosted GURGAON - MANESAR on the website for all practical purposes. Director Town and Country Planning, Haryana and / or its employees will not be liable under any condition TO KUNDLI for any legal action/damages direct or indirect arising from the use of this development plan. URBAN COMPLEX - 2031 AD The user is requested to convey any discrepancy observed in the data to Sh. Dharm Rana, GIS Developer (IT), SULTANPUR e-mail id- [email protected], mob. no. 98728-77583. SAIDPUR-MOHAMADPUR DRAFT DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR CONTOLLED AREAS V-2(b) 300m 1 Km 800 500m TO BADLI BADLI TO DENOTED ON DRG.NO.-D.T.P.(G)1936 DATED 16.04.2010 5Km DELHI - HARYANA BOUNDARY PATLI HAZIPUR SULTANPUR TOURIST COMPLEX UNDER SECTION 5 (4) OF ACT NO. 41 OF 1963 AND BIRDS SANTURY D E L H I S T A T E FROM REWARI KHAINTAWAS LEGEND:- H6 BUDEDA BABRA BAKIPUR 100M. WIDE K M P EXPRESSWAY V-2(b) STATE BOUNDARY WITH 100M.GREEN BELT ON BOTH SIDE SADHRANA MAMRIPUR MUNICIPAL CORPORATION BOUNDARY FROM PATAUDI V-2(b) 30 M GREEN BELT V-2(b) H5 OLD MUNICIPAL COMMITTEE LIMIT 800 CHANDU 510 CONTROLLED AREA BOUNDARY 97 H7 400 RS-2 HAMIRPUR 30 M GREEN BELT DHANAWAS VILLAGE ABADI 800 N A J A F G A R H D R A I N METALLED ROAD V-2(b) V2 GWS CHANNEL -

File No.EIC II-221001/3/2019-O/O (SE)Sewerage System(Oandm) 647 I/3206/2021

File No.EIC II-221001/3/2019-O/o (SE)Sewerage System(OandM) 647 I/3206/2021 GURUGRAM METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY, GURUGRAM File No. E-214/20/2018-O/o SE-Infra-II/74 Dated: 09.02.2021 To Registrar General, National Green Tribunal New Delhi Subject: Action Taken Report in the case of O.A. No.523/2019 title Vaishali Rana Chandra vs UOI Reference: This is in continuation to this office letter no. E-214/20/2018-O/o SE- Infra-II/65 dated 05.02.2021 with reference to order dt 07.09.2020 in the case of OA 523/2019 Vaishali Rana & Ors. Vs UOI & Ors and letter dated 14.10.2020 received from Sh. Anil Grover, Sr. Additional Advocate, Haryana with request to provide response to Hon’ble NGT on points mentioned as under: 1. Preparation of proper Action Plan with timelines to mitigate the effect of “reduction in recharge capacity” due to concretization of Badshahpur Drain, dealing with estimated loss of recharge capacity and contents of OA No. 523/2019 in coordination with MCG & HSVP. 2. Report in compliance of the same is attached herewith and be perused instead of report sent earlier vide office letter no. E-214/20/2018-O/o SE-Infra-II/65 dt 5.2.2021 Report submitted for kind consideration and further necessary action please. Superintending Engineer, Infra-II Gurugram Metropolitan Development Authority Gurugram CC to 1. Chief Executive Officer, GMDA, Gurugram 2. Commissioner, Municipal Corporation Gurugram 3. Chairman, HSPCB, Panchkula 4. Chief Engineer, Infra-II, GMDA, Gurugram 5. -

Integrated Mobility Plan for Gurgaon Manesar Urban Complex

December 2010 Department of Town and Country Planning (DTCP), Government of Haryana Integrated Mobility Plan for Gurgaon Manesar Urban Complex Support Document 5th Floor ‘A’ Wing, IFCI Tower Nehru Place New Delhi 110019 www.umtc.co.in Integrated Mobility Plan for Gurgaon- Manesar Urban Complex TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PRIMARY DATA COLLECTED ............................................................................. 2 1.1 Traffic Surveys Conducted .............................................................................. 2 1.2 Survey Schedule .......................................................................................... 2 1.3 Road Network Inventory ................................................................................. 6 1.4 Screen - line Volume Counts ............................................................................ 7 1.5 Cordon Volume Counts & RSI Surveys .................................................................. 9 1.6 Road Side Interview Surveys ........................................................................... 13 1.7 Occupancy ................................................................................................ 15 1.8 Intersection Classified Volume Counts ............................................................... 17 1.9 Speed and Delay Surveys ............................................................................... 31 1.10 On- street Parking Surveys ............................................................................. 34 1.11 Off - Street Parking Surveys -

Revision of Group Housing Project

At For Client-M/s JUVENTUS ESTATE LTD July, 2018 Schedule: 8 (b), Category: B Built Up Area – 3, 61,332 sqm QCI Certificate no. NABET/EIA/1619/RA 0064 PREPARED BY GRASS ROOTS RESEARCH & CREATION INDIA (P) LTD. (Accredited by QCI/NABET, Approved by MoEFCC, GoI, ISO 9001:2008 Certified Co.) F-374-375, Sector-63, Noida, U.P. Ph.: 0120- 4044630, Telefax: 0120- 2406519 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: http://www.grc-india.com GRC INDIA TRAINING & ANALYTICAL LABORATORY (Accredited by NABL, Recognized by MoEFCC, GoI) A unit of GRC India CONTENTS S.NO. DESCRIPTION PAGE NO. I Basic Information 1-3 II Activity 3-13 III Environmental Sensitivity 13-15 IV Terms of Reference 15-19 Expansion & Modification of Group Housing Colony, FORM I At Village –Dhanwapur, Sector-104, Gurugram, Haryana FORM- I S. No. Item Details 1. Name of the project/s Expansion & Modification of Group Housing Colony Project 2. S. No. in the schedule 8 (b) 3. Proposed Plot Area = 1,37,685.79 m2 capacity/area/length/tonnage to be Built-up Area = 3,61,332 m2 handled/command area/lease area/number of wells to be drilled 4. New/Expansion/Modernization Expansion and Modification 5. Existing Capacity/Area etc. Existing Built-up area = 3,75,674.82 m2 (as per accorded EC) 6. Category of Project i.e. ‘A’ or ‘B’ Category B 7. Does it attract the general condition? No If yes, please specify. 8. Does it attract the specific No condition? If yes, please specify. 9. -

![DA 3DA Hrcj `W ]`Dz X >Fd]Z^D](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6517/da-3da-hrcj-w-dz-x-fd-z-d-1666517.webp)

DA 3DA Hrcj `W ]`Dz X >Fd]Z^D

# 6# 4 & "7 "7 7 VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"#0$"T utqBVQWBuxy( #%&'#()*+ 0 - .!+/ +1 #5$3; $ %3.3#18.(93 (3:%$.213($3# 4$.5./%012' (523.(5/(31$ '3: :31%5:3/: %531483:5 :2(.$ %21.%#:2# 3.3: 3#.$#%234:4<+= 4$5:34/1 594$:3(34A)39'343 >. % !"<?##$ ?* >3 $ &3 , - *./)01 )+2 !) & ''( ! * ( '! & ' ./%012' people in the rally being Muslims, she asked the minori- n their first joint rally, the top ties to vote en bloc for the BSP- ( Iguns of Uttar Pradesh SP-RLD alliance after accusing Opposition grand alliance on the Congress of trying to split ) Sunday targeted both the BJP the anti-BJP votes. “If Muslims and the Congress and cau- want BJP to lose, they have to )3/ tioned the minority commu- stand firmly behind gathband- nity not to waste their votes by han. The alliance is winning, eaders of the two Kashmir- backing the Congress. provided they don’t tamper Lbased regional parties, the In a massive show of with the Electronic Voting National Conference and the strength in Saharanpur district, Machines (EVMs),” said People Democratic Party, on which goes to polls in the first Mayawati, adding that the vot- Sunday staged protest demon- phase on April 11, BSP supre- ers would end the “drama of strations against ban on move- mo Mayawati, SP chief chowkidari”. ment of civilian vehicle on the " Akhilesh Yadav and Rashtriya Modi, the BSP leader said, national highway between Lok Dal leader Ajit Singh has not fulfilled even one Baramulla and Udhampur and amid tight security arrange- ban on Srinagar-Jammu addressed the rally, and fourth of the promises he made %"& $" ' ) $* provoked common people to ments. -

Reviewing the Status of Compliance of Directions of the Hon'ble Supreme Court and NGT for Rejuvenation of River Yamuna

Item No. 01 Court No. 1 BEFORE THE NATIONAL GREEN TRIBUNAL PRINCIPAL BENCH, NEW DELHI Original Application No. 06/2012 Manoj Mishra Applicant Versus Union of India & Ors. Respondent(s) Date of hearing: 27.01.2021 CORAM: HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE ADARSH KUMAR GOEL, CHAIRPERSON HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE SHEO KUMAR SINGH, JUDICIAL MEMBER HON’BLE DR. NAGIN NANDA, EXPERT MEMBER Respondent(s): Ms. Jyoti Mendiratta, Advocate for GNCTD Mr. Anil Grover, Senior AAG with Mr. Rahul Khurana, Advocate for State of Haryana & HSPCB Mr. H.S. Phoolka Senior, Advocate with Ms. Sakshi Popli, Advocate for DJB Mr. Raj Kumar, Advocate for CPCB ORDER I. Issue under consideration: Reviewing the status of compliance of directions of the Hon'ble Supreme Court and NGT for rejuvenation of river Yamuna 1. This order is in continuation of earlier orders on the subject. The issue under consideration is rejuvenation of River Yamuna through execution of directions of this Tribunal’s order dated 13.01.2015 (2015 SCC Online NGT 840) (“the 2015 order”) in this matter, and further orders including orders dated 08.05.2015 (2015 SCC Online NGT 841) and dated 07.12.2017 in OA 65 of 20161 and OA 76 of 20162. We may mention that 1 Manoj Misra v. Delhi Development Authority & Ors. 2 Pramod Kumar Tyagi Vs. Art of Living International Center & Ors. 1 the Hon’ble Supreme Court also issued several directions for improving water quality of river Yamuna, and protection of floodplains, to which reference is made later herein. Finally, vide order dated 24.4.2017, the Court transferred proceedings before it in W.P. -

DBA-VOTING-LIST-2018.Pdf

Sl.No. Name Address Bar Council Bar No. Phone Phone T.U.P. H.No-322/14, Jacubpura, 1 A.L.Sahni P/1007/1983 2 2321473 9313401837 Gurgaon H.No-763-A, Ist Floor, 2 Aakash Aggarwal Block-H, Palam Vihar, P/695/1999 4 9350840785 9910991353 Gurgaon. V.P.O. Dhunela, Post 3 Aakil Ali P/3239/2014 4051 9050300395 9813313823 Office Sohna, Gurgaon H.No-249,Sector-17-A 4 Aarti Bhalla P/2016/2015 4246 9350320004 Gurgaon. H.No-224/7, H.B. 5 Aarti Hans Colony, Sec-7 Ext, P/1398/2011 3061 9910383914 Gurgaon Vill- Udaka, PO-Sohna, 6 Aazad P/3601/2009 2544 9711115701 Distt- Gurgaon Gandhi Nagar Ward No. 7 Abdul Hamid 8 Opp Mewat Model P/778/1994 4054 8860481185 School Tauru. Vill-Rewasan, Teh -Nuh, 8 Abdul Rehman P/95/1998 6 9416256151 9813039030 Distt-Gurgaon PWO Housing Complex, B-2/301, Sector 43, 9 Abha Sinha Sushant Lok-I, Gurgaon P/1800/1999 4751 9871957449 At(P) C-6/6360, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi H.No-645/20, Gali No-6, 10 Abhai singh Yadav P/514/1977 3100 9250171144 Shivji Park, Gurgaon Abhey singh H.No.1434, Sec-15, Part- 0124- 11 P/1132/2001 8 9811198319 Dahima II, Gurgaon. 6568432 Resi-Vill-Dhanwa Pur, Abhey Singh 12 Po-Daulta Bad, Distt- P/857/1995 9 9811934070 Dahiya Gurgaon H.No-209/4, Subhash 13 Abhey Singla P/420/2007 2008 9999499932 9811779952 Nagar, Gur. H.No. 225, sector 15, 14 Abhijeet Gupta P/4107/2016 4757 9654010101 Part-I, Gurgaon. -

Project Report Template

MAHINDRA - TERI CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR SUSTAINABLE HABITATS Water Sustainability Assessment Of Gurugram City Water Sustainability Assessment of Gurugram City © The Energy and Resources Institute 2021 Suggested format for citation T E R I. 2021 Water Sustainability Assessment of Gurugram City New Delhi: The Energy and Resources Institute. 82 pp. THE TEAM Technical Team Mr Akash Deep, Senior Manager, GRIHA Council Ms Tarishi Kaushik, Research Associate, TERI Support Team Mr Dharmender Kumar, Administrative Officer, TERI Technical Reviewer Prof. Arun Kansal, Dean (Research and Relationships), TERI School of Advanced Studies, New Delhi For more information Project Monitoring Cell T E R I Tel. 2468 2100 or 2468 2111 Darbari Seth Block E-mail [email protected] IHC Complex, Lodhi Road Fax 2468 2144 or 2468 2145 New Delhi – 110 003 Web www.teriin.org India India +91 • Delhi (0)11 Preface Literature describes urban areas as open systems with porous boundaries and highlights the importance of a systems perspective for understanding ecological sustainability of human settlement. Similarly, a socio-ecological framework helps us to understand the nexus between social equity, environmental sustainability, and economic efficiency. India is urbanizing rapidly with characteristic inequality and conflicts across the social, economic, and locational axes. Following the global pattern, Indian cities use social and natural resources of the rural hinterland and their own resources for survival and growth and, in the process, generate large amount of waste. Water is the most important ‘resource flow’ in an urban area, driven by a complex set of intersecting socio-economic, political, infrastructural, hydrological, and other factors. These drivers vary a great deal within a city and has a significant impact on the water flow and management and requires both micro and macro level study in order to address it. -

HEALTH DEPARTMENT Gurugram Integrated Disease Surveillance Program Email :- [email protected] Media Bulletin on COVID-19 Dated 09-06-2020

HEALTH DEPARTMENT Gurugram Integrated Disease Surveillance Program Email :- [email protected] Media Bulletin on COVID-19 dated 09-06-2020 World health organization (WHO) has recently declared the Novel Corona Virus COVID-19 as pandemic. In Order to contain the spread of the virus, Haryana Govt. has strengthened the surveillance and control measures against the diseases. The detailed status of surveillance activity for COVID-19. Cumulative No. of Passengers/Persons put on surveillance till date 23650 Cumulative No. of Passengers/Persons who have completed surveillance period of 14 days 18600 New Case Reported Today 164 01 Case Linked with 4 Marla , Gurugram 01 Case Linked with 8 Marla, Gurugram 03 Case Linked with Adarsh Nagar , Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Alipur , Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Arjun Nagar , Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Ashok Vihar , Gurugram 02 Case Linked with Basai village, Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Bhim Nagar , Gurugram 03 Case Linked with Bhondsi, Gurugram 04 Case Linked with Budhera, Gurugram 02 Case Linked with Chakkarpur , Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Village- Chakkarpur, Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Dhanwapur, Gurugram 164 03 Case Linked with DLF Phase 1 , Gurugram 03 Case Linked with DLF Phase 2 , Gurugram 02 Case Linked with DLF Phase 3, Gurugram 02 Case Linked with DLF Phase 4, Gurugram 04 Case Linked with DLF Phase 5, Gurugram 02 Case Linked with Farrukh Nagar, Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Fazilpur Dhani, Gurugram 04 Case Linked with Gandhi Nagar, Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Gari Harsaru, Gurugram -

Municipal Corporation Gurugram Irfilpfiomar'

\l \. Corporation Gurugram List ofVICC Center Municipal ted ofll.('r who will d Desitna tion ofDesigna Place ofVoter obiections ward DesiSna tion of receive the claims and a;. Name of lnformation & No oflice r Appolnted Revising Officer collection Cenaer as llelPing -lr7tU,rJ /{,r.1t. AuthoritY GPS Chonta For Revis RaiKumar )BT Saint 5oLdrer Distt- Fishries DDP0 Gunrgram I SchoolNew Palam Oflice.. Gurugram (Sh. DeePak vihar Ph 1 Choma Wing) Yadav) (Ri8ht cPs. Bhawani ]BT 9416479920 Commun ity Centre CarteaPuri 2 BDP0 Gurugratn sector 23 Sharma C.rte.Puri (Left csss A,av PTI -NTFa;;kl,nag-ai Senior SecndorY Dundahera SchoolVillage Dundahera (Right s"rriJ beslSzelzc RrILr 5ec. Schooi 4 secy MKT Comm sDo (c) N orth Village Sarhol Gurugram CuruBram (Sh. cPs Bharat thushell Deepti IBT ii. Sec School ChakarPur Cogia, HCS) 5 SDO (PRl. CuruSram CartarPuri 9729322217 Eoluoe z il r+o'isrt'z>z ved praka sh Clerk Sr. Sec. School 6 NT Badsbapur thim Garh Kheri 0/o CDP0-1 I5279b'.r4Oii Raiiv Gandhi hi8h lndrawatj NT Pataudi Raiendra 3 sDo(c) Pataudi Raiender School Park (Sh. Ravinder Part se.-9 4g99sstcs' I Yadav HCJ) Kumar IRT aPs Covi. High School Naresh 82952?9991 B Secy M.C DhanwaPur t FarukhnaSar G;vt. colleBe ? 4ztl14 O2i Covt Cotlege Sector Birendea 9 Tehsildar Farrukh Sec'9 9 Curugram ; NaBar 9868154 /ll SKT 6SSS Sec'{/7 school Neela,o I *"tr"r" Govt Sr. Sec C.E.o. Sheetla 10 biitrlct Teacher i4 Gurugram sec tor 4, GCM Mata,GuruSram, 0fficer. tz.t lvtt (Sh. vatsal frinai CSSS Sec 4/7 981t n.nd Publr( s;t.lyoti vashisth) HCS DsCo (A8ri), lr 7 Teacher 921600003 Curu8ram Sahool Sedor New 9t17179985q Dharmendtr TR GPS wazirabad sifloai-*si s"i i 12 NT ColonY school Ge€ta Bhaw.n new i Colotly Gurugram I Govt. -

General Areas Water

M/S MARIANA ENVIRONMENTAL CLEARANCE FOR PROPOSED EXPANSION INFRASTRUCTURE OF COMMERCIAL COMPLEX LOCATED AT SECTOR-104, Form-1A LIMITED VILLAGE- DHANWAPUR, GURGAON, HARYANA FORM-1 A 1.0 LAND ENVIRONMENT 1.1. Will the existing land use get significantly altered from the project that is not consistent with the surroundings? (Proposed land use must conform to the approved Master Plan / Development Plan of the area. Change of land use, if any and the statutory approval from the competent authority be submitted). Attach Maps of (i) site location, (ii) surrounding features of the proposed site (within 500 meters) and (iii) the site (indicating levels & contours) to appropriate scales. If not available attach only conceptual plans. The Proposed Expansion of Commercial Complex Located at Sector-104, Village- Dhanwapur, Gurgaon, Haryana. The proposed site is for commercial development. The following maps are attached. (i) Site location, (ii) Layout ( Conceptual ) plan, (iii) Surrounding features of the proposed site (within 500 meters and 10 Km, Ref. Annexure 1.2 List out all the major project requirements in terms of the land area, built up area, water consumption, power requirement, connectivity, community facilities, parking needs etc. The proposed Expansion of Commercial Complex Located at Sector-104, Village- Dhanwapur, Gurgaon, Haryana. The brief description of the proposed project is given below in Table-1: Table-1: Brief description of the Project SN Description Quantity Unit GENERAL 1 Gross Plot Area (Licensed Area) 8574.26 SQM 2 Net Planned