10. Lessons from Gurgaon, India's Private City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

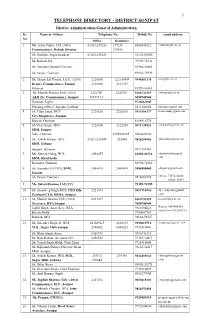

1 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY - DISTRICT SONIPAT District Administration/General Administration Sr

1 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY - DISTRICT SONIPAT District Administration/General Administration Sr. Name of Officer Telephone No. Mobile No. email address No. Office Residence 1. Ms. Anita Yadav, IAS (2004) 01262-255253 279233 8800540222 [email protected] Commissioner, Rohtak Division 274555 Sh. Gulshan, Superintendent 01262-255253 94163-80900 Sh. Rakesh, PA 99925-72241 Sh. Surender, Reader/Commnr. 98964-28485 Sh. Sanjay, Gunman 89010-19999 2. Sh. Shyam Lal Poonia, I.A.S., (2010) 2220500 2221500-F 9996801370 [email protected] Deputy Commissioner, Sonipat 2220006 2221255 Gunman 83959-00363 3. Sh. Munish Sharma, IAS, (2014) 2222700 2220701 8368733455 [email protected] Addl. Dy. Commissioner, Sonipat 2222701,2 9650746944 Gunman, Jagbir 9728661005 Planning Officer, Joginder Lathwal 9813303608 [email protected] 4. Sh. Uday Singh, HCS 2220638 2220538 9315304377 [email protected] City Magistrate, Sonipat Rakesh, Gunman 8168916374 5. Sh .Vijay Singh, HCS 2222100 2222300 9671738833 [email protected] SDM, Sonipat Inder, Gunman 8395900365 9466821680 6. Sh. Ashish Kumar, HCS, 01263-252049 252050 9416288843 [email protected] SDM, Gohana Sanjeev, Gunman 9813759163 7. Ms. Shweta Suhag, HCS, 2584055 82850-00716 sdmkharkhoda@gmail. SDM, Kharkhoda com Ravinder, Gunman 80594-76260 8. Sh . Surender Pal, HCS, SDM, 2460810 2460800 9888885445 [email protected] Ganaur Sh. Pawan, Gunman 9518662328 Driver- 73572-04014 81688-19475 9. Ms. Saloni Sharma, IAS (UT) 78389-90155 10. Sh. Amardeep Singh, HCS, CEO Zila 2221443 9811710744 dy.ceo.zp.snp@gmail. Parishad CEO, DRDA, Sonipat com 11. Sh. Munish Sharma, IAS, (2014) 2221937 8368733455 [email protected] Secretary, RTA Sonipat 9650746944 Jagbir Singh, Asstt. Secy. RTA 9463590022 Rakesh-9467446388 Satbir Dvr-9812850796 Rajesh Malik 7700007784 Ramesh, MVI 94668-58527 12. -

Making Gurgaon the Next Silicon Valley Over the Last Two Decades, Gurgaon Has Emerged As One of Top Locations for IT-BPM Companies Not Only in India but Globally

Making Gurgaon The Next Silicon Valley Over the last two decades, Gurgaon has emerged as one of top locations for IT-BPM companies not only in India but globally. It is home to not only various MNC’s (including many Fortune 500 companies) and large Indian companies but also many SMEs. Growth of the IT/BPM industry has been one of the key drivers behind the development of Gurgaon and its emergence as the “Millennium City”. i) Gurgaon houses about 450 IT-BPM companies employing close to 3.0 lakh professionals directly and 9 lakh indirectly. ii) 76% of employees from Indian IT-BPM industry are < 30 years of age; women constitute 31% of the workforce of which 45% are fresh intakes from campus. Similar trends apply to Gurgaon. iii) Gurgaon contributes 7-8% of Haryana’s State GDP. iv) 10-12% of total Indian IT-BPM employees work out of Gurgaon. v) Gurgaon contributes to a total of about 7% of Indian IT-BPM exports. Clearly, Gurgaon and IT/BPM industry has been a great partnership. They have grown together and contributed to each other’s development. However, in the last few years we have noticed stagnation and even a dip in Gurgaon’s contribution to the Indian IT/BPM industry. While in absolute terms the revenues from the city may still be increasing, clearly in relative terms there is a downfall in the overall contribution. Data shows that not as many companies are setting up centres in Gurgaon as was the case 5 years back. Many state governments have recognized IT-BPM industry as an imperative source of mass employment and economic development empowering large sections of societies and are taking measures to attract the industry. -

International Public Health Hazards: Indian Legislative Provisions

“International public health hazards: Indian legislative provisions” presents an outline of the provisions in the Indian legal system which may enable the implementation of IHR in the country. International Health Regulations (2005) are International public health hazards: the international legal instrument designed to help protect all countries from the international spread of disease, including public health risks and public health Indian legislative provisions emergencies. The present document is the result of a study taken up for the regional workshop on public health legislation for International Health Regulations, Yangon, Myanmar,” 8–10 April 2013. The relevant Indian legislation in the various Acts and rules that may assist in putting early warning systems in place has been outlined. The document intends to provide a ready reference on Indian legislation to enable establishing an early warning system that could assist the Government to provide health care. ISBN 978-92-9022-476-1 World Health House Indraprastha Estate Mahatma Gandhi Marg New Delhi-110002, India 9 7 8 9 2 9 0 2 2 4 7 6 1 International public health hazards: Indian legislative provisions WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. International public health hazards: Indian legislative provisions 1. Health Legislation 2. Public Health 3. National Health Programs I. India. ISBN 978-92-9022-476-1 (NLM classification: W 32) Cover photo: © http://parliamentofindia.nic.in/ © World Health Organization 2015 All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – can be obtained from SEARO Library, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi 110 002, India (fax: +91 11 23370197; e-mail: [email protected]). -

Directory of Officers Office of Director of Income Tax (Inv.) Chandigarh Sr

Directory of Officers Office of Director of Income Tax (Inv.) Chandigarh Sr. No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Address Contact Details (Sh./Smt./Ms/) 1 P.S. Puniha DIT (Inv.) Room No. - 201, 0172-2582408, Mob - 9463999320 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2587535 Sector-2, Panchkula e-mail - [email protected] 2 Adarsh Kumar ADIT (Inv.) (HQ) Room No. - 208, 0172-2560168, Mob - 9530765400 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2582226 Sector-2, Panchkula 3 C. Chandrakanta Addl. DIT (Inv.) Room No. - 203, 0172-2582301, Mob. - 9530704451 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2357536 Sector-2, Panchkula e-mail - [email protected] 4 Sunil Kumar Yadav DDIT (Inv.)-II Room No. - 207, 0172-2583434, Mob - 9530706786 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2583434 Sector-2, Panchkula e-mail - [email protected] 5 SurendraMeena DDIT (Inv.)-I Room No. 209, 0172-2582855, Mob - 9530703198 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2582855 Sector-2, Panchkula e-mail - [email protected] 6 Manveet Singh ADIT (Inv.)-III Room No. - 211, 0172-2585432 Sehgal Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2585432 Sector-2, Panchkula 7 Sunil Kumar Yadav DDIT (Inv.) Shimla Block No. 22, SDA 0177-2621567, Mob - 9530706786 Complex, Kusumpti, Fax-0177-2621567 Shimla-9 (H.P.) e-mail - [email protected] 8 Padi Tatung DDIT (Inv.) Ambala Aayakar Bhawan, 0171-2632839 AmbalaCantt Fax-0171-2632839 9 K.K. Mittal Addl. DIT (Inv.) New CGO Complex, B- 0129-24715981, Mob - 9818654402 Faridabad Block, NH-IV, NIT, 0129-2422252 Faridabad e-mail - [email protected] 10 Himanshu Roy ADIT (Inv.)-II New CGO Complex, B- 0129-2410530, Mob - 9468400458 Faridabad Block, NH-IV, NIT, Fax-0129-2422252 Faridabad e-mail - [email protected] 11 Dr.Vinod Sharma DDIT (Inv.)-I New CGO Complex, B- 0129-2413675, Mob - 9468300345 Faridabad Block, NH-IV, NIT, Faridabad e-mail - [email protected] 12 ShashiKajle DDIT (Inv.) Panipat SCO-44, Near Angel 0180-2631333, Mob - 9468300153 Mall, Sector-11, Fax-0180-2631333 Panipat e-mail - [email protected] 13 ShashiKajle (Addl. -

India in the Indian Ocean Donald L

Naval War College Review Volume 59 Article 6 Number 2 Spring 2006 India in the Indian Ocean Donald L. Berlin Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Berlin, Donald L. (2006) "India in the Indian Ocean," Naval War College Review: Vol. 59 : No. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol59/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen Berlin: India in the Indian Ocean INDIA IN THE INDIAN OCEAN Donald L. Berlin ne of the key milestones in world history has been the rise to prominence Oof new and influential states in world affairs. The recent trajectories of China and India suggest strongly that these states will play a more powerful role in the world in the coming decades.1 One recent analysis, for example, judges that “the likely emergence of China and India ...asnewglobal players—similar to the advent of a united Germany in the 19th century and a powerful United States in the early 20th century—will transform the geopolitical landscape, with impacts potentially as dramatic as those in the two previous centuries.”2 India’s rise, of course, has been heralded before—perhaps prematurely. How- ever, its ascent now seems assured in light of changes in India’s economic and political mind-set, especially the advent of better economic policies and a diplo- macy emphasizing realism. -

Government of Haryana Department of Revenue & Disaster Management

Government of Haryana Department of Revenue & Disaster Management DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN Sonipat 2016-17 Prepared By HARYANA INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION, Plot 76, HIPA Complex, Sector 18, Gurugram District Disaster Management Plan, Sonipat 2016-17 ii District Disaster Management Plan, Sonipat 2016-17 iii District Disaster Management Plan, Sonipat 2016-17 Contents Page No. 1 Introduction 01 1.1 General Information 01 1.2 Topography 01 1.3 Demography 01 1.4 Climate & Rainfall 02 1.5 Land Use Pattern 02 1.6 Agriculture and Cropping Pattern 02 1.7 Industries 03 1.8 Culture 03 1.9 Transport and Connectivity 03 2 Hazard Vulnerability & Capacity Analysis 05 2.1 Hazards Analysis 05 2.2 Hazards in Sonipat 05 2.2.1 Earthquake 05 2.2.2 Chemical Hazards 05 2.2.3 Fires 06 2.2.4 Accidents 06 2.2.5 Flood 07 2.2.6 Drought 07 2.2.7 Extreme Temperature 07 2.2.8 Epidemics 08 2.2.9 Other Hazards 08 2.3 Hazards Seasonality Map 09 2.4 Vulnerability Analysis 09 2.4.1 Physical Vulnerability 09 2.4.2 Structural vulnerability 10 2.4.3 Social Vulnerability 10 2.5 Capacity Analysis 12 2.6 Risk Analysis 14 3 Institutional Mechanism 16 3.1 Institutional Mechanisms at National Level 16 3.1.1 Disaster Management Act, 2005 16 3.1.2 Central Government 16 3.1.3 Cabinet Committee on Management of Natural Calamities 18 (CCMNC) and the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) 3.1.4 High Level Committee (HLC) 18 3.1.5 National Crisis Management Committee (NCMC) 18 3.1.6 National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) 18 3.1.7 National Executive Committee (NEC) 19 -

Ward Wise List of Sector Officers, Blos & Blo Supervisors, Municipal

WARD WISE LIST OF SECTOR OFFICERS, BLOS & BLO SUPERVISORS, MUNICIPAL CORPORATION, GURUGRAM Sr. Constit Old P S Ward Sector Officer Mobile No. New Name of B L O Post of B L O Office Address of B L O Mobile No Supervisior Address Mobile No. No. uenc No No. P S No 1 B 15 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 15 Nirmala AWW Pawala Khushrupur 9654643302 Joginder Lect. HIndi GSSS Daultabad 9911861041 (Jahajgarh) 2 B 26 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 26 Roshni AWW Sarai alawardi 9718414718 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 3 B 28 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 28 Anand AWW Choma 9582167811 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 4 B 29 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 29 Rakesh Supervisor XEN Horti. HSVP Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 5 B 30 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 30 Pooja AWW Sarai alawardi 9899040565 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 6 B 31 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 31 Santosh AWW Choma 9211627961 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 7 B 32 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 32 Saravan kumar Patwari SEC -14 -Huda 8901480431 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 8 B 33 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 33 Vineet Kumar JBT GPS Sarai Alawardi 9991284502 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 9 B 34 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 34 Roshni AWW Sarai Alawardi 9718414718 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 10 B 36 1 Sh. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -8 HARYANA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII-A&B VILLAGE, & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DIST.RICT BHIWANI Director of Census Operations Haryana Published by : The Government of Haryana, 1995 , . '. HARYANA C.D. BLOCKS DISTRICT BHIWANI A BAWAN I KHERA R Km 5 0 5 10 15 20 Km \ 5 A hAd k--------d \1 ~~ BH IWANI t-------------d Po B ." '0 ~3 C T :3 C DADRI-I R 0 DADRI - Il \ E BADHRA ... LOHARU ('l TOSHAM H 51WANI A_ RF"~"o ''''' • .)' Igorf) •• ,. RS Western Yamuna Cana L . WY. c. ·......,··L -<I C.D. BLOCK BOUNDARY EXCLUDES STATUtORY TOWN (S) BOUNDARIES ARE UPDATED UPTO 1 ,1. 1990 BOUNDARY , STAT E ... -,"p_-,,_.. _" Km 10 0 10 11m DI';,T RI CT .. L_..j__.J TAHSIL ... C. D . BLOCK ... .. ~ . _r" ~ V-..J" HEADQUARTERS : DISTRICT : TAHSIL: C D.BLOCK .. @:© : 0 \ t, TAH SIL ~ NHIO .Y'-"\ {~ .'?!';W A N I KHERA\ NATIONAL HIGHWAY .. (' ."C'........ 1 ...-'~ ....... SH20 STATE HIGHWAY ., t TAHSil '1 TAH SIL l ,~( l "1 S,WANI ~ T05HAM ·" TAH S~L j".... IMPORTANT METALLED ROAD .. '\ <' .i j BH IWAN I I '-. • r-...... ~ " (' .J' ( RAILWAY LINE WIT H STA110N, BROAD GAUGE . , \ (/ .-At"'..!' \.., METRE GAUGE · . · l )TAHSIL ".l.._../ ' . '1 1,,1"11,: '(LOHARU/ TAH SIL OAORI r "\;') CANAL .. · .. ....... .. '" . .. Pur '\ I...... .( VILLAGE HAVING 5000AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME ..,." y., • " '- . ~ :"''_'';.q URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE- CLASS l.ltI.IV&V ._.; ~ , POST AND TELEGRAPH OFFICE ... .. .....PTO " [iii [I] DEGREE COLLE GE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION.. '" BOUNDARY . STATE REST HOuSE .TRAVELLERS BUNGALOW AND CANAL: BUNGALOW RH.TB .CB DISTRICT Other villages having PTO/RH/TB/CB elc. -

I. Read the Given Passage Carefully. the Sultanpur National Park and Bird Sanctuary Is Located in Gurgaon District of Haryana

CLASS NOTES CLASS:5 TOPIC: REVISION WORKSHEET SUBJECT:ENGLISH I. Read the given passage carefully. The Sultanpur National Park and Bird Sanctuary is located in Gurgaon district of Haryana. This National park has a lake called Sultanpur Jheel which is a habitat of a number of or organisms like crustaceans, fish and insects. The lake is a home for many resident birds like Black Francolin, Indian Rotter and migratory birds like Siberian cranes and Great Flamingos and antelopes like Blue Bulls and Black Bucks. But what’s left today is the dry bed of the lake that is covered with fish bones and Neelgai carrion. The only life forms visible across its vast expanse are the tiny baby frogs, which jump from one dry crack in the lake’s bed to another and stray cattle from neighbouring villages. The lake is dry since it did not receive its share of water from the western Yamuna canal. The canal owned by the Haryana government’s Irrigation department would not supply water to lake. Water is being diverted to farmers for irrigation purposes. Read the questions and choose the correct answer from the options given below: 1. Where is Sultanpur Park located? a. Delhi b. Gurgaon c. Sultanpur d. Noida 2. Name the migratory bird that arrives in Sultanpur National Park. a. Great Flamingo b. Black Francolin c. Indian Rotter d. Sparrow 3. What is the only life form left on the dry bed of Sultanpur National Park? a. baby frogs b. Neelgai carrion c. fish bones d. all of these 4. -

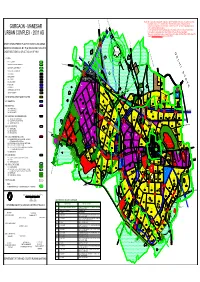

GURGAON - MANESAR on the Website for All Practical Purposes

FROM FARUKHNAGAR FROM FARUKHNAGAR NOTE: This copy is a digitised copy of the original Development Plan notified in the Gazette.Though precaution has been taken to make it error free, however minor errors in the same cannot be completely ruled out. Users are accordingly advised to cross-check the scanned copies of the notified Development plans hosted GURGAON - MANESAR on the website for all practical purposes. Director Town and Country Planning, Haryana and / or its employees will not be liable under any condition TO KUNDLI for any legal action/damages direct or indirect arising from the use of this development plan. URBAN COMPLEX - 2031 AD The user is requested to convey any discrepancy observed in the data to Sh. Dharm Rana, GIS Developer (IT), SULTANPUR e-mail id- [email protected], mob. no. 98728-77583. SAIDPUR-MOHAMADPUR DRAFT DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR CONTOLLED AREAS V-2(b) 300m 1 Km 800 500m TO BADLI BADLI TO DENOTED ON DRG.NO.-D.T.P.(G)1936 DATED 16.04.2010 5Km DELHI - HARYANA BOUNDARY PATLI HAZIPUR SULTANPUR TOURIST COMPLEX UNDER SECTION 5 (4) OF ACT NO. 41 OF 1963 AND BIRDS SANTURY D E L H I S T A T E FROM REWARI KHAINTAWAS LEGEND:- H6 BUDEDA BABRA BAKIPUR 100M. WIDE K M P EXPRESSWAY V-2(b) STATE BOUNDARY WITH 100M.GREEN BELT ON BOTH SIDE SADHRANA MAMRIPUR MUNICIPAL CORPORATION BOUNDARY FROM PATAUDI V-2(b) 30 M GREEN BELT V-2(b) H5 OLD MUNICIPAL COMMITTEE LIMIT 800 CHANDU 510 CONTROLLED AREA BOUNDARY 97 H7 400 RS-2 HAMIRPUR 30 M GREEN BELT DHANAWAS VILLAGE ABADI 800 N A J A F G A R H D R A I N METALLED ROAD V-2(b) V2 GWS CHANNEL -

File No.EIC II-221001/3/2019-O/O (SE)Sewerage System(Oandm) 647 I/3206/2021

File No.EIC II-221001/3/2019-O/o (SE)Sewerage System(OandM) 647 I/3206/2021 GURUGRAM METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY, GURUGRAM File No. E-214/20/2018-O/o SE-Infra-II/74 Dated: 09.02.2021 To Registrar General, National Green Tribunal New Delhi Subject: Action Taken Report in the case of O.A. No.523/2019 title Vaishali Rana Chandra vs UOI Reference: This is in continuation to this office letter no. E-214/20/2018-O/o SE- Infra-II/65 dated 05.02.2021 with reference to order dt 07.09.2020 in the case of OA 523/2019 Vaishali Rana & Ors. Vs UOI & Ors and letter dated 14.10.2020 received from Sh. Anil Grover, Sr. Additional Advocate, Haryana with request to provide response to Hon’ble NGT on points mentioned as under: 1. Preparation of proper Action Plan with timelines to mitigate the effect of “reduction in recharge capacity” due to concretization of Badshahpur Drain, dealing with estimated loss of recharge capacity and contents of OA No. 523/2019 in coordination with MCG & HSVP. 2. Report in compliance of the same is attached herewith and be perused instead of report sent earlier vide office letter no. E-214/20/2018-O/o SE-Infra-II/65 dt 5.2.2021 Report submitted for kind consideration and further necessary action please. Superintending Engineer, Infra-II Gurugram Metropolitan Development Authority Gurugram CC to 1. Chief Executive Officer, GMDA, Gurugram 2. Commissioner, Municipal Corporation Gurugram 3. Chairman, HSPCB, Panchkula 4. Chief Engineer, Infra-II, GMDA, Gurugram 5. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Reference to Paragraphs Page Preface vii Overview ix Chapter – 1 Introduction Budget profile 1.1 1 Application of resources of the State Government 1.2 1 Persistent savings 1.3 2 Funds transferred directly to the State implementing 1.4 2 agencies Grants-in-aid from Government of India 1.5 3 Planning and conduct of audit 1.6 3 Significant audit observations and response of Government 1.7 4 to audit Recoveries at the instance of audit 1.8 4 Lack of responsiveness of Government to Audit 1.9 5 Follow-up on Audit Reports 1.10 5 Status of placement of Separate Audit Reports of 1.11 6 autonomous bodies in the State Assembly Year-wise details of reviews and paragraphs appeared in 1.12 7 Audit Report Chapter – 2 Performance Audit Public Health Engineering Department 2.1 9 Sewerage Schemes Urban Local Bodies Department 2.2 27 Working of Urban Local Bodies Education Department (Haryana School Shiksha Pariyojna Parishad) 2.3 46 Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan Rural Development Department 2.4 66 Indira Awaas Yojna Cooperation Department 2.5 80 Working of Cooperation Department Reference to Paragraphs Page Chapter – 3 Compliance Audit Civil Aviation Department Irregularities in the functioning of Civil Aviation 3.1 99 Department Civil Secretariat 3.2 102 Irregular expenditure Allotment of space to banks without execution of agreement 3.3 104 Development and Panchayat Department 3.4 105 Management of panchayat land Food and Supplies Department Loss due to distribution of foodgrains to ineligible ration 3.5 110 card holders Health and Medical