Corrigin Grevillea), Proteaceae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ne Wsletter No . 92

AssociationAustralian of NativeSocieties Plants for Growing Society (Australia)Australian IncPlants Ref No. ISSN 0725-8755 Newsletter No. 92 – August 2012 GSG Vic Programme 2012 GSG SE Qld Programme 2012 Leader: Neil Marriott Morning tea at 9.30am, meetings commence at 693 Panrock Reservoir Rd, Stawell, Vic. 3380 10.00am. For more information contact Bryson Phone: 03 5356 2404 or 0458 177 989 Easton on (07) 3121 4480 or 0402242180. Email: [email protected] Sunday, 26 August Contact Neil for queries about program for the year. This meeting has been cancelled as many members Any members who would like to visit the official have another function to attend over the weekend. collection, obtain cutting material or seed, assist in its maintenance, and stay in our cottage for a few days The October 2012 meeting – has been are invited to contact Neil. After the massive rains at replaced by a joint excursion through SEQ & the end of 2010 and the start of 2011 the conditions northern NSW commencing on Wednesday, 7 are perfect for large scale replanting of the collection. November 2012. GSG members planning to attend Offers of assistance would be most welcome. are asked to contact Jan Glazebrook & Dennis Cox Newsletter No. 92 No. Newsletter on Ph (07) 5546 8590 for full details closer to this Friday, 29 September to Monday, 1 October event. See also page 3 for more details. SUBJECT: Spring Grevillea Crawl Sunday, 25 November FRI ARVO: Meet at Neil and Wendy Marriott’s Panrock VENUE: Home of Robyn Wieck Ridge, 693 Panrock Reservoir Rd, Stawell Lot 4 Ajuga Court, Brookvale Park Oakey for welcome and wander around the HONE (07) 4691 2940 gardens. -

Scope Item Implementation

NARROGIN DISTRICT THREATENED FLORA MANAGEMENT PROGRAM Annual Report 2004 Marie Strelein and Greg Durell For the Narrogin District Threatened Flora Recovery Team Department of Conservation and Land Management PO Box 100 Narrogin WA 6312 SUMMARY 2004 Threatened Flora recovery within the Narrogin District is a collaborative project between the Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM), the Commonwealth Department of Environment and Heritage (through the NHT program) the Avon Catchment Council (ACC), the Southwest Catchment Council (SWCC), the Botanic Gardens and Parks Authority (BGPA) and the community. CALM supports the program by providing both direct and indirect funding, including the full time employment of a Conservation Officer. Funds have been received from the Avon and Southwest Catchment Councils through NHT 2 and allocated to on-ground recovery actions. Funding has also been obtained from NHT for the development of Interim Recovery plans for several Narrogin District threatened plant species. The BGPA has provided direct costs to the program for two species recovery projects. The community has provided significant in- kind volunteer support to implement many of the recovery actions. CALM’s Narrogin District manages ten Critically Endangered flora (CR), eleven Endangered flora (EN) and sixteen Vulnerable Flora (VU) flora. All are Declared as Rare Flora under the Wildlife Conservation Act (1950). In addition, 213 flora species are listed for the Narrogin District on CALM’s Priority Flora List. Many of these require additional monitoring and survey to determine their threatened status. Highlights of the program for 2004 are: • A report summarising the Darwinia carnea (CR) translocation process from 1997 through to 2004 and assessing whether the translocation has met the aims outlined in the translocation proposal was completed in December 2004 by Leonie Monks. -

Monitoring and Prioritisation of Flora Translocations: a Survey of Opinions from Practitioners and Researchers

MONITORING AND PRIORITISATION OF FLORA TRANSLOCATIONS: A SURVEY OF OPINIONS FROM PRACTITIONERS AND RESEARCHERS N. Hancock1, R.V. Gallagher1 & R.O. Makinson2 1. Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University 2. Royal Botanic Gardens & Domain Trust, Sydney i This document was compiled as part of a project funded by the NSW Biodiversity Research Hub in 2013-14. It is intended to be read in conjunction with the Australian Network for Plant Conservation publication Guidelines for the translocation of threatened plants in Australia (Vallee et al. 2004). Please cite this publication as: Hancock, N., Gallagher, R.V. & Makinson, R.O. (2014). Monitoring and prioritisation of flora translocations: a survey of opinions from practitioners and researchers. Report to the Biodiversity Hub of the NSW Office of Environment & Heritage. For further correspondence contact: [email protected] ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary v Acknowledgements v List of Tables vi RESULTS OF SURVEY OF PRACTITIONERS AND RESEARCHERS Section 1 A synthesis of opinions on monitoring of flora translocations – results from the Flora translocation survey (2013) 1. The Flora Translocation Survey (2013) 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Aims and objectives of the survey 1 1.3 What is a successful translocation? 2 1.4 The importance of monitoring 2 2. Survey design 2.1 Selection of survey respondents 3 2.2 Survey format 4 2.3 Data analysis 5 3. Survey results: quantitative data 3.1 General information 5 3.2 Monitoring duration by habit groups 6 3.3 Monitoring duration by breeding system 8 3.4 Monitoring duration by planting method 10 3.5 Monitoring duration by taxonomic groups 11 3.6 Other life-cycle monitoring 3.6.1 Early survivorship 13 3.6.2 Growth 13 4. -

(Proteaceae) with Emphasis on Banksia Cuneata, a Rare and Endangered Species

Heredity 79 (1997)394—40 1 Received 24 September 1996 Genetic diversity in Banksia and Dryandra (Proteaceae) with emphasis on Banksia cuneata, a rare and endangered species TINA L. MAGUIRE & MARGARET SEDGLEY* Department of Horticulture, Viticulture and Qenology, The University of Adelaide, Waite Campus, P/ant Research Centre, PMB 1, Glen Osmond, SA 5064, Australia Randomamplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers were investigated as a tool for estimat- ing genetic diversity within 33 species of Banksia and three species of Diyandra. Three primers were used on DNA from 10 seeds per species, and band data were pooled to give between 52 and 89 bands per species, most of which were polymorphic. Genetic diversity was calculated using six published metrics on three species, for which allozyme data were also available. Based on between-method consistency, three metrics were chosen for analysis of the full data set. Levels of genetic diversity in Banksia and Diyandra ranged from 0.59 to 0.90. Based on this information, a detailed study was conducted on all 10 known populations of B. cuneata, a rare and endangered species, with a restricted geographical distribution in south-western Australia. Estimates of genetic diversity ranged from 0.65 to 0.74, which is high for a rare and endan- gered species. Analysis of molecular variance (AM0vA)wasused to partition RAPD variation within and between populations. Nearly all of the variation was attributable to individuals within populations, indicating a lack of population divergence. It is suggested that the combination of bird pollination and high outcrossing rates in B. cuneata maintain genetic diversity and cohesion between the populations. -

The Following Is the Initial Vaughan's Australian Plants Retail Grafted Plant

The following is the initial Vaughan’s Australian Plants retail grafted plant list for 2019. Some of the varieties are available in small numbers. Some species will be available over the next few weeks. INCLUDING SOME BANKSIA SP. There are also plants not listed which will be added to a future list. All plants are available in 140mm pots, with some sp in 175mm. Prices quoted are for 140mm pots. We do not sell tubestock. Plants placed on hold, (max 1month holding period) must be paid for in full. Call Phillip Vaughan for any further information on 0412632767 Or via e-mail [email protected] Grafted Grevilleas $25.00ea • Grevillea Albiflora • Grevillea Alpina goldfields Pink • Grevillea Alpina goldfields Red • Grevillea Alpina Grampians • Grevillea Alpina Euroa • Grevillea Aspera • Grevillea Asparagoides • Grevillea Asparagoides X Treueriana (flaming beauty) • Grevillea Baxteri Yellow (available soon) 1 • Grevillea Baxteri Orange • Grevillea Beadleana • Grevillea Biformis cymbiformis • Grevillea Billy bonkers • Grevillea Bipinnatifida "boystown" • Grevillea Bipinnatifida "boystown" (prostrate red new growth) • Grevilllea Bipinnatifida deep burgundy fls • Grevillea Bracteosa • Grevillea Bronwenae • Grevillea Beardiana orange • Grevillea Bush Lemons • Grevillea Bulli Beauty • Grevillea Calliantha • Grevillea Candelaborides • Grevillea Candicans • Grevillea Cagiana orange • Grevillea Cagiana red • Grevillea Crowleyae • Grevillea Droopy drawers • Grevillea Didymobotrya ssp involuta • Grevillea Didymobotrya ssp didymobotrya • Grevillea -

RECOVERY TEAM ANNUAL REPORT THREATENED SPECIES AND/OR COMMUNITIES RECOVERY TEAM PROGRAM INFORMATION Recovery Team Great Southern

RECOVERY TEAM ANNUAL REPORT THREATENED SPECIES AND/OR COMMUNITIES RECOVERY TEAM PROGRAM INFORMATION Recovery Team Great Southern District Threatened Flora & Communities Recovery Team Reporting Period Calendar year 2010 Current membership Member Representing 1. Chair Peter Lacey DEC Great Southern District, Narrogin 2. Greg Durell DEC Great Southern District, Narrogin 3. Brett Beecham DEC Wheatbelt Region 4 Andrew Brown DEC Species and Communities Branch 5. Anne Rick Lakes District Rare Flora Group, Landholder 6 Jill Richardson NRM Groups – Katanning Landcare Zone, Blackwood Basin Group 7 Peter Denton Transport and Utilities Main Roads WA – Narrogin (Wheatbelt South) 8 Val Crowley Volunteer/Community Groups 9 Judy Williams Volunteer/Community Groups 10 Anne Cochrane DEC Science Division, Flora Conservation and Herbarium Program 11 Bob Dixon Botanic Gardens and Parks Authority 12 Wendy Chow DEC Species and Communities Branch 13 Julian Murphy Local Government Authorities Dates meetings were held May 7, 2010. A second meeting was planned for November. However, it was decided to wait until the permanent flora officer was back from Parental Leave and the meeting was held in early 2011. One to two paragraph Numerous surveys were undertaken of threatened flora populations summary of achievements throughout 2010 in the Great Southern District, with emphasis on translocations, species included in the Caring for Our Country (CFOC) ‘Reducing the impact of rabbits on threatened flora’ project and on Critically Endangered species and other Declared Rare taxa that had not been surveyed for some time. This survey work highlighted the need for a more rigorous monitoring approach. A prioritisation process was implemented to produce a list of 66 Threatened Flora populations to be surveyed and have permanent monitoring quadrats installed. -

Dryandra Study - Group

DRYANDRA STUDY - GROUP. NEWSLETTE,R.NO. 23 Dryandra pulchella ISSN: 0728-ISIX January 1993 SOCIETY FOR GROWING AUSTRALIAN PLANTS LEADER NEWSLETTER EDITOR Mrs. Margaret Pieroni Mr. Tony Cavanagh 16 Calpin Cres. 16 Woodlands Dr. ATTADALE OCEAN GROVE W.A. 6156 VIC. 3226 Welcome to the first Newsletter of 1993. It is a little later than usual and I do apologise but Christmas holidays are always a difficult time to motivate oneself. I know Victorians are famous for talking about the weather but this summer has been something to talk about! We have had the wettest spring period on record followed by a mild early summer. The last few days have been heatwave conditions punctuated with violent tropical downpours. This unusual weather pattern has been accompanied by some of the worst humidity I can remember since I left Queensland. I suspect this summer will be a bad one for dryandras and many other Proteaceae - I have already lost at least 6 smaller but well established dryandras and several larger plants and it is so frustrating not to be able to do anything about it. In this Newsletter, I have included a number of smaller articles from various smut-ces. Many of the field observations have as usual comee frmm Margaret and1 think we are all very lucky that she is such a keen observer in the field. Several of these notes deal with possible hybrids or unusual forms and Margaret and I would both appreciate any other information on this aspect. So far, there are no recognised or botanically established hybrids but it would be surprising if somedidn't exist. -

Grevillea Scapigera)

CORRIGIN GREVILLEA (GREVILLEA SCAPIGERA) RECOVERY PLAN Department of Environment and Conservation Kensington Recovery Plan for Grevillea scapigera FOREWORD Interim Recovery Plans (IRPs) are developed within the framework laid down in Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) [now Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC)] Policy Statements Nos. 44 and 50. Note: the Department of CALM formally became the Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) in July 2006. DEC will continue to adhere to these Policy Statements until they are revised and reissued. IRPs outline the recovery actions that are required to urgently address those threatening processes most affecting the ongoing survival of threatened taxa or ecological communities, and begin the recovery process. DEC is committed to ensuring that Threatened taxa are conserved through the preparation and implementation of Recovery Plans (RPs) or IRPs, and by ensuring that conservation action commences as soon as possible and, in the case of Critically Endangered (CR) taxa, always within one year of endorsement of that rank by the Minister. This Interim Recovery Plan results from a review of, and replaces Wildlife Management Program No 24, Corrigin Grevillea Recovery Plan, Rossetto et al (2000). This Interim Recovery Plan will operate from June 2004 to May 2009 but will remain in force until withdrawn or replaced. It is intended that, if the taxon is still ranked Critically Endangered, this IRP will be reviewed after five years and the need for a full Recovery Plan will be assessed. This IRP was given DEC regional approval on 13 February, 2006 and was approved by the Director of Nature Conservation on 22 February, 2006. -

PERTH, TUESDAY, 5 AUGUST 2008 No. 134

!200800134GG! WESTERN 3469 AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT ISSN 1448-949X PRINT POST APPROVED PP665002/00041 PERTH, TUESDAY, 5 AUGUST 2008 No. 134 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY JOHN A. STRIJK, GOVERNMENT PRINTER AT 3.30 PM © STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA CONTENTS PART 1 Page Local Government Act 1995—Town of Vincent—Parking and Parking Facilities Amendment Local Law 2008.................................................................................................. 3485 Wildlife Conservation Act 1950— Wildlife Conservation (Rare Flora) Notice 2008(2) ........................................................... 3471 Wildlife Conservation (Specially Protected Fauna) Notice 2008(2).................................. 3477 ——— PART 2 Consumer and Employment Protection.................................................................................... 3487 Deceased Estates ....................................................................................................................... 3493 Fisheries..................................................................................................................................... 3487 Justice......................................................................................................................................... 3488 Local Government...................................................................................................................... 3488 Minerals and Petroleum ............................................................................................................ 3489 Planning -

Guidelines for the Translocation of Threatened Plants in Australia

Guidelines for the Translocation of Threatened Plants in Australia Third Edition Editors: L.E. Commander, D.J. Coates, L. Broadhurst, C.A. Offord, R.O. Makinson and M. Matthes © Australian Network for Plant Conservation, 2018 Information in this publication may be reproduced provided that any extracts are acknowledged National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Guidelines for the translocation of threatened plants in Australia. 3rd ed. ISBN-13: 978-0-9752191-3-3 1. Plant conservation - Australia. 2. Plant communities - Australia. 3. Endangered plants - Australia. I. Commander, Lucy Elizabeth, 1981- . II. Australian Network for Plant Conservation. 333.95320994 First Published 1997 Reprinted 1998 Second Edition 2004 Third Edition 2018 Cover design: TSR Hub Cover photograph: Translocation site of Banksia brownii in south-west WA. (Photo: A Cochrane). Printed by IPG Marketing Solutions, 25 Strathwyn Street, Brendale, QLD 4500 This publication should be cited as: Commander, L.E., Coates, D., Broadhurst, L., Offord, C.A., Makinson, R.O. and Matthes, M. (2018) Guidelines for the translocation of threatened plants in Australia. Third Edition. Australian Network for Plant Conservation, Canberra. For more information about the Australian Network for Plant Conservation please contact: ANPC National Office GPO Box 1777, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia Phone: + 61 (0)2 6250 9509 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.anpc.asn.au Table of Contents Foreword .............................................................................................................................................................................................v -

Summary Annual Report

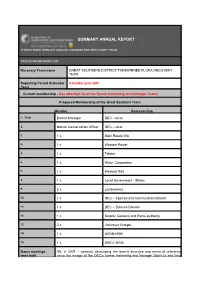

SUMMARY ANNUAL REPORT THREATENED SPECIES AND/OR COMMUNITIES RECOVERY TEAM PROGRAM INFORMATION Recovery Team name GREAT SOUTHERN DISTRICT THREATENED FLORA RECOVERY TEAM Reporting Period (Calendar Calendar year 2007 Year) Current membership - See attached list of the former Katanning and Narrogin Teams Proposed Membership of the Great Southern Team Member Representing 1. Chair District Manager DEC – local 2. Nature Conservation Officer DEC – local 3. 1 x Main Roads WA 4. 1 x Western Power 5. 1 x Telstra 6. 1 x Water Corporation 7. 1 x Westnet Rail 8. 1 x Local Government - Shires 9. 2 x Landowners 10. 1 x DEC – Species and Communities Branch 11. 1 x DEC – Science Division 12. 1 x Botanic Gardens and Parks Authority 13. 2 x Volunteer Groups 14. 1 x AVON NRM 15. 1 x SWCC NRM Dates meetings NIL in 2007 – currently developing the team’s structure and terms of reference were held since the merger of the DEC’s former Katanning and Narrogin District’s and thus the two recovery teams. One to two Numerous surveys were undertaken of threatened flora populations throughout paragraph 2007 in the Great Southern District, with emphasis on Critically Endangered summary of species and other Declared Rare taxa that had not been surveyed for some time. achievements Successful searches were conducted in an attempt to locate new populations of suitable for Critically Endangered species. Overlaying soil and vegetation types, particular to WATSNU individual species requirements using desktop GIS mapping, identified potential search areas. Two new populations of Caladenia melanema (with more areas of suitable habitat located for further survey in 2008), one population of Caladenia graniticola and one population of Verticordia fimbrilepis subsp. -

In Vitro Propagation of the Rare and Endangered Grevillea Scapigera

HORTSCIENCE 27(3):261-262. 1992. 0.5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) plus 0.05% Tween 80, followed by immersion in In Vitro Propagation of the Rare and distilled water. Bleached, damaged, or un- wanted leaf and stem material was removed. Endangered Grevillea scapigera Each shoot was then immersed in 0.5% NaOCl only for »5 to 10 sec, washed in sterile distilled water, then placed in 30-ml (Proteaceae) polycarbonate tubes (one explant/tube) with Eric Bunn and Kingsley W. Dixon sterile filter paper domes for support and containing 10 ml of liquid medium. The fil- Kings Park and Botanic Garden, Kings Park, West Perth, Western ter paper domes were autoclaved twice at Australia 6005 121C for 15 min. Lloyd and McCown’s Additional index words. micropropagation, leaf culture, adventitious shoots, in vivo (1981) Woody Plant Medium (WPM) sup- plemented with WPM vitamins, 500 µM myo- rooting inositol, 60 mM sucrose, 20 µM zeatin ri- Abstract. Micropropagation, including adventitious shoot growth from leaf sections, boside, and 2 µM GA,, and pH 6.0 was au- was achieved for Grevillea scapigera (Proteaceae), a rare and endangered species from toclaved at 121C for 20 min in 250-ml media Western Australia. Shoot tips were initiated on filter paper supports with liquid WPM bottles and poured into culture tubes. The tubes with their explants were incubated in (Woody Plant Medium) and supplemented with 20 µM zeatin riboside and 2 µM GA3. Shoots were then incubated on WPM solidified with agar and supplemented with 5 µM the dark for 1 week. kinetin and 0.5 µM BA, which produced an approximate 6-fold multiplication rate per Sterile shoot and bud cultures were moved month.