Paula Guerra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Second Grade Music Curriculum

Second Grade General Music Units September: October: November: December: January: Music Elements Music Elements Composition Performance Performance Rhythm Meter Rhythmic Composition Rhythmic Composition Performance Rhythmic Notation Intro to Meter Compose 8 measure Continue work on Practice using drum Top number rhythmic rhythmic Sticks& Pads Rhythmic Values Bottom number composition composition Counting Procedures -Mrs. Music May I? Bar Lines Review Dynamics Class work Practice performing -Rhythmic Pac Man Measure Add Dynamics original rhythmic -Musical Math Musical Rest to composition compositions Measure Completion Review Rough Performance Add other rhythm band Performance Draft with teacher Special Celebrations; instruments Special Celebrations: Performance Final draft (Songs & Activities) Perform composition (Song & activities) Special Celebrations: Graded Project Hanukkah for class Welcome Back songs (Songs & Activities) Kwanzaa Graded performance Character Ed Songs Fire Safety Songs Performance Christmas Performance Apple Songs Columbus Songs (Special Celebrations) Character Ed Special Celebrations: Butterfly Cycle Halloween Songs -Hiawatha Rhythm (Songs & Activities) th September 11 -Patriot Red Ribbon Songs Story -Month of the Year Rap Day Rhythm Pumpkin Patch -Thanksgiving Songs -Bundled Up September 17th- -I’m Thankful… -Martin Luther King Songs Constitution Day -Character Ed -Winter Songs February: March: April: May: June: Performance Music In Our Schools Music Elements Music Elements Performance Performance -

"World Music" and "World Beat" Designations Brad Klump

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 17:23 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Origins and Distinctions of the "World Music" and "World Beat" Designations Brad Klump Canadian Perspectives in Ethnomusicology Résumé de l'article Perspectives canadiennes en ethnomusicologie This article traces the origins and uses of the musical classifications "world Volume 19, numéro 2, 1999 music" and "world beat." The term "world beat" was first used by the musician and DJ Dan Del Santo in 1983 for his syncretic hybrids of American R&B, URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014442ar Afrobeat, and Latin popular styles. In contrast, the term "world music" was DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014442ar coined independently by at least three different groups: European jazz critics (ca. 1963), American ethnomusicologists (1965), and British record companies (1987). Applications range from the musical fusions between jazz and Aller au sommaire du numéro non-Western musics to a marketing category used to sell almost any music outside the Western mainstream. Éditeur(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Klump, B. (1999). Origins and Distinctions of the "World Music" and "World Beat" Designations. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 19(2), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014442ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des des universités canadiennes, 1999 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

American Rock with a European Twist: the Institutionalization of Rock’N’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20Th Century)❧

75 American Rock with a European Twist: The Institutionalization of Rock’n’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20th Century)❧ Maria Kouvarou Universidad de Durham (Reino Unido). doi: dx.doi.org/10.7440/histcrit57.2015.05 Artículo recibido: 29 de septiembre de 2014 · Aprobado: 03 de febrero de 2015 · Modificado: 03 de marzo de 2015 Resumen: Este artículo evalúa las prácticas desarrolladas en Francia, Italia, Grecia y Alemania para adaptar la música rock’n’roll y acercarla más a sus propios estilos de música y normas societales, como se escucha en los primeros intentos de las respectivas industrias de música en crear sus propias versiones de él. El trabajo aborda estas prácticas, como instancias en los contextos francés, alemán, griego e italiano, de institucionalizar el rock’n’roll de acuerdo con sus propias posiciones frente a Estados Unidos, sus situaciones históricas y políticas y su pasado y presente cultural y musical. Palabras clave: Rock’n’roll, Europe, Guerra Fría, institucionalización, industria de música. American Rock with a European Twist: The Institutionalization of Rock’n’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20th Century) Abstract: This paper assesses the practices developed in France, Italy, Greece, and Germany in order to accommodate rock’n’roll music and bring it closer to their own music styles and societal norms, as these are heard in the initial attempts of their music industries to create their own versions of it. The paper deals with these practices as instances of the French, German, Greek and Italian contexts to institutionalize rock’n’roll according to their positions regarding the USA, their historical and political situations, and their cultural and musical past and present. -

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

Ramones 2002.Pdf

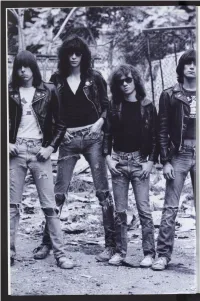

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Christian Ricci Behind the Scenes in New York – Fall 2020 Assignment #1 October 05, 2020 1 Opened in 1973 on Bowery in Manhatt

Christian Ricci Behind the Scenes in New York – Fall 2020 Assignment #1 October 05, 2020 Opened in 1973 on Bowery in Manhattan’s East Village, CBGB was a bar and music venue which features prominently in the history of American punk rock, New Wave and Hardcore music genres. The club’s owner, Hilly Kristal, was always involved with music and musicians, having worked as a manager at the legendary jazz club Village Vanguard booking acts like Miles Davis. When CBGB first opened its doors in the early seventies the venue featured mostly country, blue grass, and blues acts (thus CBGB) before transitioning over to punk rock acts later in the decade. Many well know performers of the punk rock era received their start and earliest exposure at the club, including the Ramones, Patti Smith, Television, Blondie, and Joan Jett. During the New Wave era, performers like Elvis Costello, Talking Heads and even early performances from the Police graced the stage in the now legendary venue. Located at 315 Bowery, which is situated near the northern section of Bowery before it splits into 3rd and 4th Avenues at Cooper square, the original building on the site was constructed in 1878 and was used as a tenement house for 10 families with a shop (liquor store) on the ground floor. In 1934, 315 and 313 were combined into one building and the façade was redesigned and constructed in the Art Deco style, as documented in the 1940 tax photo. At that time, the building was occupied by the Palace Hotel with a ground floor saloon. -

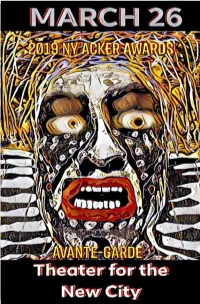

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

Seite 1 Von 2 04.08.2013

Seite 1 von 2 Guru Guru biography "We`re not cosmic rock, we`re comic rock." Mani Neumeier, 1973 A free form jazz mentality, avoiding musical clichés and commercialism, has always characterized the music and philosophies of German freak `n roll band GURU GURU who have categorically occupied their own special stage within the realms of modern music. From it`s LSD induced origins in the late `60s to it`s present day configuration which still rocks and grooves with intensity, countless personnel changes have occurred making it more of a succession of musical ventures and concepts under the moniker GURU GURU, which came about as a tongue-in-cheek reference to the BEATLES and their guru worshipping of the late `60s. GURU GURU were one of the first bands to become associated with the German Krautrock movement from that era along with bands such as XHOL CARAVAN, AMON DUUL and CAN. However, the band was not partial to the absurd stereo-typing and preferred the terms "acid space" or simply, "acid rock" which better described their loud, trippy, improvisational music. The constant driving force behind GURU GURU since it`s inception as THE GURU GURU GROOVE BAND in 1968 has been the MP3, Free Download (stream) unusual intellect and masterful musicianship of drummer MANI NEUMEIER. During the first half of the 1960s he embraced the jazz interpretations of JOHN COLTRANE, THELONIOUS MONK, MAX ROACH and other jazz mentors from which he would Tour & shows updates develop his own style of impulsive drumming. During this period he played with various traditional jazz groups in Zurich, Press & news updates Switzerland culminating with work with Swiss jazz pianist IRENE SCHWEIZER.