Ico Mel How Gamers Experience Informal Digital Learning of English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 of 279 FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS

FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS. January 01, 2012 to Date 2019/06/19 TITLE / EDITION OR ISSUE / AUTHOR OR EDITOR ACTION RULE MEETING (Titles beginning with "A", "An", or "The" will be listed according to the (Rejected / AUTH. DATE second/next word in title.) Approved) (Rejectio (YYYY/MM/DD) ns) 10 DAI THOU TUONG TRUNG QUAC. BY DONG VAN. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 DAI VAN HAO TRUNG QUOC. PUBLISHER NHA XUAT BAN VAN HOC. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 POWER REPORTS. SUPPLEMENT TO MEN'S HEALTH REJECTED 3IJ 2013/03/28 10 WORST PSYCHOPATHS: THE MOST DEPRAVED KILLERS IN HISTORY. BY VICTOR REJECTED 3M 2017/06/01 MCQUEEN. 100 + YEARS OF CASE LAW PROVIDING RIGHTS TO TRAVEL ON ROADS WITHOUT A APPROVED 2018/08/09 LICENSE. 100 AMAZING FACTS ABOUT THE NEGRO. BY J. A. ROGERS. APPROVED 2015/10/14 100 BEST SOLITAIRE GAMES. BY SLOANE LEE, ETAL REJECTED 3M 2013/07/17 100 CARD GAMES FOR ALL THE FAMILY. BY JEREMY HARWOOD. REJECTED 3M 2016/06/22 100 COOL MUSHROOMS. BY MICHAEL KUO & ANDY METHVEN. REJECTED 3C 2019/02/06 100 DEADLY SKILLS SURVIVAL EDITION. BY CLINT EVERSON, NAVEL SEAL, RET. REJECTED 3M 2018/09/12 100 HOT AND SEXY STORIES. BY ANTONIA ALLUPATO. © 2012. APPROVED 2014/12/17 100 HOT SEX POSITIONS. BY TRACEY COX. REJECTED 3I 3J 2014/12/17 100 MOST INFAMOUS CRIMINALS. BY JO DURDEN SMITH. APPROVED 2019/01/09 100 NO- EQUIPMENT WORKOUTS. BY NEILA REY. REJECTED 3M 2018/03/21 100 WAYS TO WIN A TEN-SPOT. BY PAUL ZENON REJECTED 3E, 3M 2015/09/09 1000 BIKER TATTOOS. -

• Natural Wonders • Urban Scenes • Stately Homes • Fabulous Fairs and Festivals Amtrak Puts Them All Within Easy Reach 2 3

Amtrak Goes Green • New York State’s Top “Green Destinations” Your Amtrak® travel guide to 35 destinations from New York City to Canada New York By Rail® • Natural wonders • Urban scenes • Stately homes • Fabulous fairs and festivals Amtrak puts them all within easy reach 2 3 20 | New York by Rail Amtrak.com • 1-800-USA-RAIL Contents 2010 KEY New york TO sTATiON SERViCES: ® m Staffed Station by Rail /m Unstaffed Station B Help with baggage Published by g Checked baggage Service e Enclosed waiting area G Sheltered platform c Restrooms a Payphones f Paid short term parking i Free short term parking 2656 South Road, Poughkeepsie, New York 12601 ■ L Free long term parking 845-462-1209 • 800-479-8230 L Paid long term parking FAX: 845-462-2786 and R Vending 12 Greyledge Drive PHOTO BY GREG KLINGLER Loudonville, New York 12211 T Restaurant / snack bar 518-598-1430 • FAX: 518-598-1431 3 Welcome from Amtrak’s President 47 Saratoga Springs QT Quik-Trak SM ticket machine PUBLISHeRS 4 A Letter from the NYS 50 Central Vermont $ ATM Thomas Martinelli Department of Transportation and Gilbert Slocum 51 Mohawk River Valley [email protected] 5 A Letter from our Publisher Schenectady, Amsterdam, Utica, Rome eDIToR/Art DIRectoR 6 Readers Write & Call for Photos Alex Silberman 53 Syracuse [email protected] 7 Amtrak®: The Green Initiative Advertising DIRectoR 55 Rochester Joseph Gisburne 9 Amtrak® Discounts & Rewards 800-479-8230 56 Buffalo [email protected] 11 New York City 57 Niagara Falls, NY 27 Hudson River Valley AD AND PRoMoTIoN -

March 2011 Shuttle

Te Shutle March 2011 The Next NASFA Meeting is 19 March 2011 at the Regular Time and Location Con†Stellation XXX ConCom Meeting 3P, 19 March The likely plan going forward will be to continue to have d Oyez, Oyez d concom meetings the same day as club meetings. As we near the con and need to go to more than one concom meeting a The next NASFA Meeting will be Saturday 19 March 2011 month, the concom schedule will have to adjust. at the regular time (6P) and the regular location. ATMM Meetings are at the Renasant Bank’s Community Room, The March After-The-Meeting Meeting will be at Adam and 4245 Balmoral Drive in south Huntsville. Exit the Parkway at Maria Grim’s house—2117 Buckingham Drive SW in Hunts- Airport Road; head east one short block to the light at Balmoral ville. See the map below. The usual NASFA rules apply, to wit, Drive; turn left (north) for less than a block. The bank is on the please bring your preferred drink plus a food item to share. right, just past Logan’s Roadhouse restaurant. Enter at the front door of the bank; turn right to the end of a short hallway. Map To The turn onto English MARCH PROGRAM Drive is about 4 miles NASFA’s March program will be “Be- ATMM south of the turn from hind the Science of Extraction Point,” Airport Road onto Memorial Parkway Parkway Memorial presented by Stephanie Osborn. Extrac- Location tion Point is Stephanie’s latest book, co- authored with Travis S. -

Pacific Locomotive Association, Inc. January 2021 WP 713 Gets a New Main Generator

THE CLUB CAR Bulletin 689 Pacific Locomotive Association, Inc. January 2021 WP 713 Gets A New Main Generator Photo by Gerry Feeney Western Pacific GP-7 #713 sits outside the Car Shop at Brightside Yard in May 2019 waiting for its main generator to be replaced. The locomotive looks good in its new paint. During the generator replacement care was taken to protect the paint job. The last time Western Pacific GP-7 perienced a ground fault. The failure IN THIS ISSUE #713 operated on a train was during prevented the locomotive from reliably the 2018 Train of Lights season. Its dy- delivering power to its traction motors 2 An YV 330 Merry Christmas namic braking capability makes it ideal which is needed to pull through the Big for controlling train speed and provid- Curve and when switching to service 3 Activities Page ing passengers with a comfortable ride, and spot the consist at the end of TOL a real asset in handling the long TOL operations. Despite its problem 713 Presidents Message 4 consist on Westward runs from Sunol limped through the 2018 TOL operation 6 General Manager Report to Niles. Back then 713 looked pretty not missing a night. In May 2019, con- spiffy having received a new coat of tractor Matt Monson along with retired 12 Tales of the Past green and orange paint during the prior SP electrician Bob Neff of Dieselmotive Summer. The dynamic brakes worked investigated the electrical problem and 15 Information Page just fine. However, 713 frequently ex- Continued on Page 8 OUR MISSION: To be an operating railroad museum for standard gauge railroading, past, present and future, with emphasis on the Western United States and special emphasis on Northern California NILES CANYON RAILWAY An YV 330 Merry Christmas We hope everyone had toys in their stockings this Christ- mas. -

Power, Innovation, and Language Creativity in an Online Community of Practice

Power, Innovation, and Language Creativity in an Online Community of Practice A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2020 Lisa Donlan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents List of figures ............................................................................................................................ 6 List of tables.............................................................................................................................. 9 Abstract ................................................................................................................................... 10 Declaration.............................................................................................................................. 11 Copyright statement .............................................................................................................. 12 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................ 13 1 Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................. 14 Rationale for research................................................................................................ 14 Research questions .................................................................................................... 15 Contributions ............................................................................................................ -

Black Lives Matter Hashtag Trend Manipulation & Memetic Warfare On

Black Lives Matter Hashtag Trend Manipulation & Memetic Warfare on Twitter // Disinformation Investigation Black Lives Matter Hashtag Trend Manipulation & Memetic Warfare on Twitter Disinformation Investigation 01 Logically.ai Black Lives Matter Hashtag Trend Manipulation & Memetic Warfare on Twitter // Disinformation Investigation Content Warning This report contains images from social media accounts and conversations that use racist language. Executive Summary • This report presents findings based on a Logically intelligence investigation into suspicious hashtag activity in conjunction with the Black Lives Matter protests and online activism following George Floyd’s death. • Our investigation found that 4chan’s /pol/ messageboard and 8kun’s /pnd/ messageboard launched a coordinated campaign to fracture solidarity in the Black Lives Matter movement by injecting false-flag hashtags into the #blacklivesmatter Twitter stream. • An investigation into the Twitter ecosystem’s response to these hashtags reveal that these hashtags misled both left-wing and right-wing communities. • In addition, complex hashtag counter offences and weaponizing of hashtag flows is becoming a common fixture during this current movement of online activism. 02 Logically.ai Black Lives Matter Hashtag Trend Manipulation & Memetic Warfare on Twitter // Disinformation Investigation The Case for Investigation Demonstrations against police brutality and systemic racism have taken place worldwide following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers Derek Chauvin, J. Alexander Kueng, Thomas Lane, and Tou Thao on May 25th 2020. This activism has also taken shape in the form of widespread online activism. Shortly after footage and images of Floyd’s death were uploaded to social media, #georgefloyd, #justiceforgeorgefloyd, and #minneapolispolice began trending. By May 28th, #blacklivesmatter, #icantbreathe, and #blacklivesmatters also began trending heavily (see Figure 1). -

Pacific Remembers Dr. Eric Hammer

University of the Pacific Masthead Logo Scholarly Commons The aP cifican University of the Pacific ubP lications 2-7-2019 The aP cifican February 7, 2019 University of the Pacific Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/pacifican Recommended Citation University of the Pacific, "The aP cifican February 7, 2019" (2019). The Pacifican. 122. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/pacifican/122 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the University of the Pacific ubP lications at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP cifican by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 110, Issue 08 www.thepacif can.com T ursday, February 07, 2019 Follow Us: T e Pacif can @T ePacif can @T ePacif can PACIFIC REMEMBERS DR. ERIC HAMMER Pacif c will host a memorial service for inspirational music professor, Dr. Eric Hammer. PC: University of the Pacif c Carlos Flores mer’s career began with his says Lauren Gibson ‘17, they personally believed they “Pacif c Hail” in his honor as Editor-in-Chief undergraduate education here who served as his Graduate were capable of.” Burns Tower began to play the at University of the Pacif c, Assistant as she earned her T e community that he school’s alma mater. Af er a _________________ where he graduated in 1973 master’s degree from Pacif c. loved, was quick to celebrate brief silence, the students and On Monday, January before earning his master’s “He taught me not just about his life, with a candlelight vigil faculty in attendance began 28th, the Pacif c communi- and doctorate degrees at the the intricacies of music, ed- being held the night that the to tell their stories of their ex- ty suf ered a loss that came University of Oregon. -

GWCCA-Annual-Report-2019-Game

GAME CHANGERS ANNUAL REPORT 2019 credits The 2019 Georgia World Congress Center Authority (GWCCA) Annual Report is published by the GWCCA Department of Marketing and Communications. Written by Kent Kimes, with design and principal photography by Ashley Gilmer. Editorial oversight by Jennifer LeMaster, Chief Administrative Officer, and Holly Richmond, Communications Director. Additional photography by Chris Helton, Mary Grace Heath, and GWCCA staff. SOURCES: Economic Impact Analysis courtesy of Peter Bluestone, Sr. Research Associate, Fiscal Research Center, Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, Georgia State University. PRINTING: Advanced Color Imaging, Inc. Digital copies of this publication and prior GWCCA annual reports are available for download at www.gwcca.org. AWARDS The GWCCA’s 2018 Annual Report received: - 2019 APEX Awards for Publication Excellence - 2019 Summit Creative Award: Bronze Category - 2019 Savvy Awards Printed Publications: Award of Excellence GREETINGS FROM THE GOVERNOR 4 CHAMPIONSHIP CAMPUS GIVES ATLANTA THE GAME-CHANGING ADVANTAGE 5 MISSION, VISION, AND VALUES 6 A LETTER FROM LEADERSHIP 7 HIGHLIGHT REEL: THE YEAR IN REVIEW 8 SUPER BOWL LIII BY THE NUMBERS 11 CHANGING THE GAME FOR GEORGIA 12 FACILITY IMPROVEMENTS COMPLEMENT MAJOR PROJECTS 18 DIGITAL SCORECARD: CULTIVATING CUSTOMER AND AUDIENCE CONNECTIONS 19 TABLE OF MORE THAN A GAME: ENHANCING QUALITY OF LIFE FOR EVERY GEORGIAN 20 2020 AND BEYOND: FUTURE EVENT FORECAST ON THE CHAMPIONSHIP CAMPUS 22 CONTENTS SAVANNAH CONVENTION CENTER: ELEVATING ITS GAME 24 GAME PLAN: VISION 2025 26 GWCCA’S GAME-CHANGING WOMEN 28 CHANGING THE GAME: CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE 30 CAREER CHANGERS: ENHANCING THE AUTHORITY LIFE EXPERIENCE 32 FINANCIAL REPORTING & ECONOMIC IMPACT 34 BOARD OF GOVERNORS 39 Like my immediate predecessor Gov. -

Students Participate in Day of Service Partner for ARCHE by Maddie Cook Staff Writer

Friday, April 15, 2011 • Volume 96, Issue 29 • nique.net Science guy inspires Bill Nye the Science Guy returns to students' lives to share scientific wisdom. 413 TechniqueThe South’s Liveliest College Newspaper Tech, Emory students participate in day of service partner for ARCHE By Maddie Cook Staff Writer Tech and Emory University are collaborat- ing on a cross-registration program that allows students at each school to take courses at the other institution, provided that the course is unique and not offered in some way at their home school. Institute President G.P. ‘Bud’ Peterson and President James Wagner of Emory have been working on developing this program. “What we are trying to do is to enhance the relationship we have with Emory to lever- age our resources,” Peterson said. Students have often requested a stronger diversity of classes from the Institute. This program aims to resolve that issue. While Tech has a wide variety of courses in engineer- ing, science and technology, it lacks in many Photos by Virginia Lin / Student Publications areas. Students participate in landscaping projects across campus on Saturday, April 9 during Tech Beautification Day. “We can’t afford to have experts and faculty This service project dates back to 1998 and involves students from every major working on numerous projects. in every area [of studies]. We can’t afford to do everything ourselves, and neither can Emory. This is a way we can make a more diversified By Aakash Arun respective projects. Approxi- painting, planting flowering manned so we’re here to help array of courses available to students,” Peter- Contributing Writer mately 1100 volunteers were plants around campus and them just like they’re there to son said. -

"Place for Friends": Teenagers, Social Networks, and Identity Vulnerability

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Dissertations Department of Sociology Winter 1-7-2012 Not Just A "Place For Friends": Teenagers, Social Networks, and Identity Vulnerability Cenate Pruitt Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss Recommended Citation Pruitt, Cenate, "Not Just A "Place For Friends": Teenagers, Social Networks, and Identity Vulnerability." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss/60 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOT JUST A “PLACE FOR FRIENDS”: TEENAGERS, SOCIAL NETWORKS, AND IDENTITY VULNERABILITY by CENATE CASH PRUITT Under the direction of Lesley Reid ABSTRACT This study is an empirical analysis of adolescents' risk management on internet social network sites such as Facebook and MySpace. Using a survey of 935 U.S. adolescents gathered by the Pew Internet and American Life Project, I investigate the influence of offline social networks on online socialization, as well as the impact of parental and self mediation tactics on risky online information-sharing practices. Overall, the relationship between offline social network strength and online communications methods was inconclusive, with results suggesting that most teens use online communications in similar ways, regardless of offline connectedness. Some relationships were discovered between parental and individual mediation tactics and risky online information sharing, largely supporting the use of active mediation techniques by parents and informed control of shared information by individual users. -

Conference Program

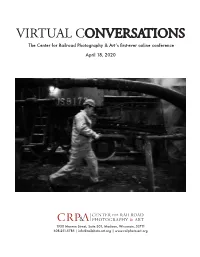

VIRTUAL CONVERSATIONS The Center for Railroad Photography & Art’s first-ever online conference April 18, 2020 1930 Monroe Street, Suite 301, Madison, Wisconsin, 53711 608-251-5785 | [email protected] | www.railphoto-art.org Contents Schedule ...................................................................................................................................................................................3 Presenters .................................................................................................................................................................................4 Images from Conference Presenters ........................................................................................................................................9 Human Connections ..............................................................................................................................................................16 CRP&A Crossword ................................................................................................................................................................18 All-Time Conference Presenters ............................................................................................................................................20 Directors, Officers & Staff .....................................................................................................................................................22 About the Center ..................................................................................................................................................................23 -

Disney Channel Serial Killers

Johnson & Wales University ScholarsArchive@JWU Honors Theses - Providence Campus College of Arts & Sciences 5-1-2021 Disney Channel Serial Killers Emily Timmins Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.jwu.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons 1 Disney Channel Serial Killers By Emily Timmins Advisor: Dr. Karen Shea Date: May 1st, 2021 2 Table of Contents 1. Abstract and Acknowledgements: pages 3-4 2. Introduction on Romanticism of Killers: pages 5-7 3. Societal Implications and Definitions: pages 7-12 4. Literature Review: pages 12-15 5. Overview of Ted Bundy and Jeffery Dahmer: pages 15-20 6. Methodology: page 21 7. Movie Review Findings: pages 21-28 8. Social Media: pages 28-46 9. Conclusion: pages 47-49 10. References: pages 50-59 Table of Figures 1. Figure 1- Comments on Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil, and Vile- Critics: page 22 2. Figure 2- Comments on Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil, and Vile- Audience Members: pages 22-23 3. Figure 3- Comments on My Friend Dahmer- Critics: pages 23-24 4. Figure 4- Comments on My Friend Dahmer- Audience Members: Page 24 5. Figure 5- Comments on Scream- Critics: Page 25 6. Figure 6- Comments on Scream- Audience: Page 26 7. Figure 7- Comments on Silence of the Lambs- Critics: Pages 26-27 8. Figure 8- Comments on Silence of the Lambs- Audience: Page 27 3 Abstract The appearance of actors Zac Efron and Ross Lynch, known for their roles as teenagers on popular Disney Channel productions, as serial killers Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer in the films Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil, and Vile and My Friend Dahmer has raised questions about the effects of these portrayals on the Generation Z demographic.