Bodicacia's Tombstone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Widescreen Weekend 2007 Brochure

The Widescreen Weekend welcomes all those fans of large format and widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and Imax – and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the best of cinema. HOW THE WEST WAS WON NEW TODD-AO PRINT MAYERLING (70mm) BLACK TIGHTS (70mm) Saturday 17 March THOSE MAGNIFICENT MEN IN THEIR Monday 19 March Sunday 18 March Pictureville Cinema Pictureville Cinema FLYING MACHINES Pictureville Cinema Dir. Terence Young France 1960 130 mins (PG) Dirs. Henry Hathaway, John Ford, George Marshall USA 1962 Dir. Terence Young France/GB 1968 140 mins (PG) Zizi Jeanmaire, Cyd Charisse, Roland Petit, Moira Shearer, 162 mins (U) or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes Omar Sharif, Catherine Deneuve, James Mason, Ava Gardner, Maurice Chevalier Debbie Reynolds, Henry Fonda, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, (70mm) James Robertson Justice, Geneviève Page Carroll Baker, John Wayne, Richard Widmark, George Peppard Sunday 18 March A very rare screening of this 70mm title from 1960. Before Pictureville Cinema It is the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The world is going on to direct Bond films (see our UK premiere of the There are westerns and then there are WESTERNS. How the Dir. Ken Annakin GB 1965 133 mins (U) changing, and Archduke Rudolph (Sharif), the young son of new digital print of From Russia with Love), Terence Young West was Won is something very special on the deep curved Stuart Whitman, Sarah Miles, James Fox, Alberto Sordi, Robert Emperor Franz-Josef (Mason) finds himself desperately looking delivered this French ballet film. -

The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Film Studies (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-2021 The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Michael Chian Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/film_studies_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chian, Michael. "The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood." Master's thesis, Chapman University, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000269 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film Studies (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood A Thesis by Michael Chian Chapman University Orange, CA Dodge College of Film and Media Arts Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Film Studies May, 2021 Committee in charge: Emily Carman, Ph.D., Chair Nam Lee, Ph.D. Federico Paccihoni, Ph.D. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Copyright © 2021 by Michael Chian III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor and thesis chair, Dr. Emily Carman, for both overseeing and advising me throughout the development of my thesis. Her guidance helped me to both formulate better arguments and hone my skills as a writer and academic. I would next like to thank my first reader, Dr. Nam Lee, who helped teach me the proper steps in conducting research and recognize areas of my thesis to improve or emphasize. -

Monday Evening September 11 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30

MONDAY EVENING SEPTEMBER 11 ÊNew Movies Sports Kids News Cox DS DR UV 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 KTBO-14 2 - - 14 New Potter’s Touch Praise (CC) Franklin J. Duplantis Graham GregLaurie.TV Praise (CC) ÊKFOR News ÊExtra Edition ÊAmerican Ninja Warrior “Las Vegas Finals Night 2” National ÊMidnight, Texas “Last Temp- ÊKFOR News (:34) The KFOR-4 4 at 6:00pm (CC) finals continue in Las Vegas. (In Stereo) (CC) tation of Midnight” Olivia and 4 at 10:00pm Tonight Show 4 4 4 4 NBC Bobo try to protect the town. (In Starring Jimmy Stereo) (CC) Fallon ÊCaso Cerrado: Edición Estelar ÊJenni Rivera: Mariposa de ÊSin senos sí hay paraíso (In ÊEl señor de los cielos (In Ste- ÊT 30 Noticias (:35) Titulares y KTUZ-30 5 30 30 30 (In Stereo) (SS) Barrio (In Stereo) (SS) Stereo) (SS) reo) (SS) más (In Stereo) TELE (SS) Dr. Phil (In Stereo) (CC) The Big Bang Kevin Can Wait Law & Order: Special Victims Law & Order: Criminal Intent The Game The Game “The KSBI-52 7 52 - 52 Theory (CC) (CC) Unit (In Stereo) (CC) “Seizure” A bisexual woman is “Parachutes ... Confession Ep- MYNET murdered. (In Stereo) (CC) Beach Chairs” isode” ÊKOCO 5 ÊWheel of ÊBachelor in Paradise “Bachelor in Paradise Season Finale” (Sea- Ê(:01) To Tell the Truth “Iliza ÊKOCO 5 (:35) Jimmy KOCO-5 News at 6pm Fortune “Teach- son Finale) (In Stereo) (CC) Shlesinger; Taye Diggs; Jana News at 10pm Kimmel Live (In 8 5 5 5 ABC (CC) er’s Week” (In Kramer; Ken Marino” Iliza (CC) Stereo) (CC) Stereo) (CC) Shlesinger; Taye Diggs. -

MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES and CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1994 MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994 A retrospective celebrating the seventieth anniversary of Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer, the legendary Hollywood studio that defined screen glamour and elegance for the world, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on June 24, 1994. MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS comprises 112 feature films produced by MGM from the 1920s to the present, including musicals, thrillers, comedies, and melodramas. On view through September 30, the exhibition highlights a number of classics, as well as lesser-known films by directors who deserve wider recognition. MGM's films are distinguished by a high artistic level, with a consistent polish and technical virtuosity unseen anywhere, and by a roster of the most famous stars in the world -- Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Judy Garland, Greta Garbo, and Spencer Tracy. MGM also had under contract some of Hollywood's most talented directors, including Clarence Brown, George Cukor, Vincente Minnelli, and King Vidor, as well as outstanding cinematographers, production designers, costume designers, and editors. Exhibition highlights include Erich von Stroheim's Greed (1925), Victor Fleming's Gone Hith the Hind and The Wizard of Oz (both 1939), Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Ridley Scott's Thelma & Louise (1991). Less familiar titles are Monta Bell's Pretty Ladies and Lights of Old Broadway (both 1925), Rex Ingram's The Garden of Allah (1927) and The Prisoner - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART 2 of Zenda (1929), Fred Zinnemann's Eyes in the Night (1942) and Act of Violence (1949), and Anthony Mann's Border Incident (1949) and The Naked Spur (1953). -

Uncivil Liberties and Libertines: Empire in Decay

Uncivil Liberties and Libertines: Empire in Decay MARIANNE MCDONALD 1. I’ve been a film nut from the time my parents would park me in a film theatre as their form of baby-sit- ting. My father invented phone vision, which was an early version of cablevision that allowed us to see newly released movies at home on our round television screen, which looked like an old Bendix washing machine. I wrote one of the earliest books on classics in cinema—and soon after, more books on the topic followed mine.1 I looked forward to seeing the films described in Ancient Rome, many of which I had not seen because I have avoided blood-fest films which invite being described with gore-filled ecstasy. (I have also avoided slasher movies, holocaust movies, and kiddie movies because they disturbed my possibly misguided sensi- bility.) The choices of films in Elena’s Theodorakopoulos’ book are all the work of interesting directors—some better than others, but the quality is, for the most part, high. The writ- ers for all these film scripts are generally outstanding. Good photography also seems to be a given. As we are told in the conclusion, “Whatever the story, spectacle is never far from Rome.” The key to assessing these treatments lies in the interpreta- tion of the portrayal of violence. Are we, the audience, ad- miring it? Calling for it, as we call for it in films by Quentin Tarentino, beginning with Reservoir Dogs (1992), or the se- ries called Saw, the seventh version (2010) now in 3-d? Do Elena Theodorakopoulos, Ancient Rome at the Cinema: Story and Spectacle in Hollywood and Rome. -

No Oscar for the Oscar? Behind Hollywood's Walk of Greed

Networking Knowledge 7(4) All About Oscar No Oscar for the Oscar? Behind Hollywood’s Walk of Greed ELIZABETH CASTALDO LUNDEN, Stockholm University ABSTRACT In 1966 the popular interest in the Academy Awards propelled Paramount Pictures to produce The Oscar (Embassy Pictures-Paramount Pictures, 1966), a film based on the homonymous novel by Richard Sale. The Oscar tells the story of an unscrupulous actor willing to do anything in his power to obtain the golden statuette, regardless of whom he has to take down along the way. Building up on fantasies of social mobility, we see the protagonist (Frankie) display his vanity, arrogance and greed to create a less than likeable character whose only hope to put his career back on track lies in obtaining the precious statuette. The movie intends to be a sneak peek behind the scenes of the biggest award ceremony, but also behind the lifestyle of the Hollywood elites, their glory and their misery as part of the Hollywood disposal machinery. Despite not being financed or officially supported by the Academy, the film intertwines elements of fiction and reality by using real footage of the event, and featuring several contemporary representatives of the movie industry such as Edith Head, Hedda Hopper, Frank and Nancy Sinatra, playing cameo roles, adding up to the inter- textual capacities of the story. Head’s participation was particularly exploited for the promotion of the film, taking advantage of her position at Paramount, her status as a multiple winner, and her role as a fashion consultant for the Academy Awards. This paper is an analytical account of the film’s production process. -

Dr. Strangelove's America

Dr. Strangelove’s America Literature and the Visual Arts in the Atomic Age Lecturer: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Stefan L. Brandt, Guest Professor Room: AR-H 204 Office Hours: Wednesdays 4-6 pm Term: Summer 2011 Course Type: Lecture Series (Vorlesung) Selected Bibliography Non-Fiction A Abrams, Murray H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. Seventh Edition. Fort Worth, Philadelphia, et al: Harcourt Brace College Publ., 1999. Abrams, Nathan, and Julie Hughes, eds. Containing America: Cultural Production and Consumption in the Fifties America. Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham Press, 2000. Adler, Kathleen, and Marcia Pointon, eds. The Body Imaged. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993. Alexander, Charles C. Holding the Line: The Eisenhower Era, 1952-1961. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana Univ. Press, 1975. Allen, Donald M., ed. The New American Poetry, 1945-1960. New York: Grove Press, 1960. ——, and Warren Tallman, eds. Poetics of the New American Poetry. New York: Grove Press, 1973. Allen, Richard. Projecting Illusion: Film Spectatorship and the Impression of Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997. Allsop, Kenneth. The Angry Decade: A Survey of the Cultural Revolt of the Nineteen-Fifties. [1958]. London: Peter Owen Limited, 1964. Ambrose, Stephen E. Eisenhower: The President. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984. “Anatomic Bomb: Starlet Linda Christians brings the new atomic age to Hollywood.” Life 3 Sept. 1945: 53. Anderson, Christopher. Hollywood TV: The Studio System in the Fifties. Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 1994. Anderson, Jack, and Ronald May. McCarthy: the Man, the Senator, the ‘Ism’. Boston: Beacon Press, 1952. Anderson, Lindsay. “The Last Sequence of On the Waterfront.” Sight and Sound Jan.-Mar. -

Movie Time Descriptive Video Service

DO NOT DISCARD THIS CATALOG. All titles may not be available at this time. Check the Illinois catalog under the subject “Descriptive Videos or DVD” for an updated list. This catalog is available in large print, e-mail and braille. If you need a different format, please let us know. Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service 300 S. Second Street Springfield, IL 62701 217-782-9260 or 800-665-5576, ext. 1 (in Illinois) Illinois Talking Book Outreach Center 125 Tower Drive Burr Ridge, IL 60527 800-426-0709 A service of the Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service and Illinois Talking Book Centers Jesse White • Secretary of State and State Librarian DESCRIPTIVE VIDEO SERVICE Borrow blockbuster movies from the Illinois Talking Book Centers! These movies are especially for the enjoyment of people who are blind or visually impaired. The movies carefully describe the visual elements of a movie — action, characters, locations, costumes and sets — without interfering with the movie’s dialogue or sound effects, so you can follow all the action! To enjoy these movies and hear the descriptions, all you need is a regular VCR or DVD player and a television! Listings beginning with the letters DV play on a VHS videocassette recorder (VCR). Listings beginning with the letters DVD play on a DVD Player. Mail in the order form in the back of this catalog or call your local Talking Book Center to request movies today. Guidelines 1. To borrow a video you must be a registered Talking Book patron. 2. You may borrow one or two videos at a time and put others on your request list. -

Cliff Harrington

“I have shaken the hand of Moses, Michelangelo and Ben Hur.” Cliff Harrington Cliff interviewing Charlton Heston, Imperial Hotel, 1976 Cliff Harrington (1932 — 2013), traveler, writer, English teacher, friend Interviewed by Allan Murphy, Tokyo 26 March, 1998 Text copyright Allan Murphy, 2017 http://www.finelinepress.co.nz "1 Preface I met Clifford (Cliff) Harrington when we both worked for an English language school in Tokyo. The English Language Education Council (ELEC) had its own seven-storey building, next to Senshu University, for over 40 years before moving to smaller premises in Jimbocho. We worked together for at least 10 years. The school's foreign teachers basically fell into one of two camps. There were the older teachers with 20 or more years of time here and to whom Japan was home. And there were the younger teachers with a maximum of five years or so here. Most were in Japan for the travel experience or what Australians refer to as "the gap year" — a break after graduating from university and before taking a full-time job at home. Needless to say, Cliff was in the former group, and I was in the latter. Of all the old hands, to me anyway, it seemed that only Cliff could truly relate to the younger staff. Typically on a Friday night after work, Cliff and half a dozen other teachers would go to a nearby pub. Along with the beer, soon travel stories would be pouring out. Everyone had some interesting experiences to share. But, whenever it became Cliff's turn, he'd easily trump all of us and then hold the floor. -

AFI PREVIEW Is Published by the Sat, Jul 9, 7:00; Wed, Jul 13, 7:00 to Pilfer the Family's Ersatz Van American Film Institute

ISSUE 77 AFI.com/Silver AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER JULY 8–SEPTEMBER 14, 2016 44T H AFI LIFE ACHIEVEMENT AWARD HONOREE A FILM RESTROSPECTIVE THE COMPOSER B EHIND THE GREAT EST A MERICAN M OVIES O F OUR TIME PLUS GLORIOUS TECHNICOLOR ★ ’90S C INEMA N OW ★ JOHN C ARPENT E R LOONEY TUNES ★ KEN ADAM REMEMBERED ★ OLIVIA DE HAVILLAND CENTENNIAL Contents AFI Life Achievement Award: John Williams AFI Life Achievement Award: July 8–September 11 John Williams ......................................2 John Williams' storied career as the composer behind many of the greatest American films and television Keepin' It Real: '90s Cinema Now ................6 series of all time boasts hundreds of credits across seven decades. His early work in Hollywood included working as an orchestrator and studio pianist under such movie composer maestros as Bernard Herrmann, Ken Adam Remembered ..........................9 Alfred Newman, Henry Mancini, Elmer Bernstein and Franz Waxman. He went on to write music for Wim Wenders: Portraits Along the Road ....9 more than 200 television programs, including the groundbreaking anthology series ALCOA THEATRE Glorious Technicolor .............................10 and KRAFT TELEVISION THEATRE. Perhaps best known for his enduring collaboration with director Steven Spielberg, his scores are among the most iconic and recognizable in film history, from the edge-of-your- Special Engagements .................. 14, 16 seat JAWS (1975) motif to the emotional swell of E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL (1982) and the haunting UCLA Festival of Preservation ...............14 elegies of SCHINDLER'S LIST (1993). Always epic in scale, his music has helped define over half a century of the motion picture medium. -

BEST FILMS of the 1950'S 1. Seven Samurai

BEST FILMS OF THE 1950’S 1. Seven Samurai - (1954, Akira Kurosawa) (Takashi Shimura, Yoshio Inaba, Toshiro Mifune) 2. On the Waterfront - (1954, Elia Kazan) (Marlon Brando, Carl Malden, Rod Steiger) 3. Vertigo - (1958, Alfred Hitchcock) (James Stewart, Kim Novak, Barbara Bel Geddes) 4. The Bridge on the River Kwai - (1957, David Lean) (Alec Guinness, William Holden) 5. The Seventh Seal -(1957, Ingmar Bergman) (Max von Sydow, Bengt Ekerot) 6. Sunset Boulevard - (1950, Billy Wilder) (Gloria Swanson, William Holden) 7. Rear Window - (1954, Alfred Hitchcock) (James Stewart, Grace Kelly) 8. Rashomon - (1951, Akira Kurosawa) (Toshiro Mifune, Masayuki Mori, Machiko Kyo) 9. All About Eve - (1950, Joseph L. Mankiewicz) Bette Davis, Anne Baxter) 10. Singin' in the Rain - (1952, Stanley Donen, Gene Kelly) Gene Kelly, Debbie Reynolds) 11. Some Like It Hot - (1959, Billy Wilder) (Jack Lemmon, Tony Curtis, Marilyn Monroe) 12. North by Northwest - (1959, Alfred Hitchcock) (Cary Grant, Eva Marie Saint) 13. Tokyo Story - (1953, Yasujiro Ozu) Chishu Ryu, Chieko Higashiyama, So Yamamura) 14. Touch of Evil - (1958, Orson Welles) Charlton Heston, Orson Welles) 15. A Streetcar Named Desire - (1951, Elia Kazan) Marlon Brando, Vivien Leigh) 16. Diabolique - (1954, Henri-Georges Clouzot) (Simone Signoret, Vera Clouzot) 17. Rebel Without a Cause - (1955, Nicholas Ray) (James Dean, Natalie Wood) 18. The African Queen - (1951, John Huston) (Catherine Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart) 19. 12 Angry Men - (1957, Sidney Lumet) (Henry Fonda, E.G. Marshall) 20. La Strada - (1954, Federico Fellini) (Giulietta Masina, Anthony Quinn) 21. Ben-Hur - (1959, William Wyler) (Charlton Heston, Jack Hawkins, Stephen Boyd) 22. Wild Strawberries - (1957, Ingmar Bergman) (Ingrid Thulin, Bibi Andersson) 23. -

03.31.21. Calendars of Rosenstein Part 1

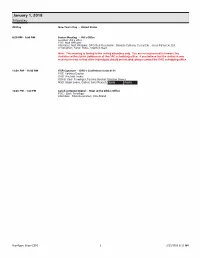

January I 1, 2018 Monday All Day New Year's Day --United States 8:20AM -9:00 AM Senior Meeting --AG's Office Location: AG's office POC: Matt Whitaker Attendees: Matt Whitaker, DAG Rod Rosenstein, Danielle Cutrona,Corey Ellis , Jesse Panuccio, Ed O'Callaghan, Sarah Flores, Stephen Boyd Note: This meeting is limited to theinvited attendees only. You are not authorized to forward this invitation without prior pennission of the OAG scheduling office. If you believethat the invitation was received in error or that other individuals should beincluded, please contact the OAG scheduling office. 11:00AM -11:30 AM FISA signature --DAG's Conference room 4111 POC: Tashina Gauhar OAG: Rachael Tucker ODAG: Zach Terwilliger,Tashina Gauhar, Brendan Groves NSD: Stuart Evans, Gabriel Sanz-Rexach,�-- 12:00PM -1:00 PM Lunch w/Rachel Brand --Meet at the DAG's Office POC: Zach Terwilliger Attendees: DAG Rosenstein, ASG Brand 1 7/22/2019 8:13 AM Flannigan, Brian (OIP) January 2, 2018 I Tuesday 8:20AM-9:00 AM Senior Meeting - AG's Office Location: AG's office POC: Matt Whitaker Attendees: Matt Whitaker, DAG Rod Rosenstein, Danielle Cutrona,Corey Ellis , Jesse Panuccio, Ed O'Callaghan, Sarah Flores, Stephen Boyd Note: This meeting is limited to the invited attendees only. You are not authorized to forward this invitation without prior pennission of the OAG scheduling office. If you believe that the invitation was received in error or that other individuals should beincluded, please contact the OAG scheduling office. 9:00AM-9:45 AM Leadership Meeting - AG's ConferenceRoom POC: Matt Whitaker Attendees: Matt Whitaker, DAG Rod Rosenstein, ASG Rachael Brand, Zach Terwilliger, Jesse Panuccio, Stephen Boyd, Peter Carr, Beth Williams, Danielle Cutrona, Rachael Tucker, Brian Morrissey, Gene Hamilton, Alice Lacour, Gary Barnett,Robert Hur, Rachel Parker, Mary Blanche Hankey, Katie Crytzer and Sarah Flores Note: This meeting is limited to the invited attendees only.