Comparing the Value of Different Types of Culture: a Study Focusing on the Perceptions of the Derbyshire Public and Managers Within the Derbyshire Cultural Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Available Property 14

Available Property 25/07/2018 to 31/07/2018 14 Properties Listed Bid online at www.rykneldhomes.org.uk 01246 217670 Properties available from 25/07/2018 to 31/07/2018 Page: 1 of 6 Address: Stephenson Place, Clay Cross, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S45 9PN Ref: 1023785 Type: 1 Bed Flat Rent: £ 78.47 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Address: Stephenson Place, Clay Cross, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S45 9PN Ref: 1023934 Type: 1 Bed Flat Rent: £ 77.86 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Address: Circular Drive, Renishaw, Derbyshire S21 3UH Ref: 1052784 Type: 2 Bed House Rent: £ 88.97 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Properties available from 25/07/2018 to 31/07/2018 Page: 2 of 6 Address: Reynard Crescent, Renishaw, Derbyshire S21 3WD Ref: 1055385 Type: 2 Bed House Rent: £ 88.97 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Address: Baker Drive, Killamarsh, Derbyshire S21 1HD Ref: 1076535 Type: 2 Bed Flat Rent: £ 84.65 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Address: Hucklow Avenue, North Wingfield, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S42 5PU Ref: 1095143 Type: 3 Bed House Rent: £ 84.53 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Properties available from 25/07/2018 to 31/07/2018 Page: 3 of 6 Address: Rocester Way, Hepthorne Lane, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S42 5LX Ref: 1097865 Type: 1 Bed Flat Rent: £ 74.99 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Address: Rocester Way, Hepthorne Lane, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S42 5LX Ref: 1097901 Type: 1 Bed Flat Rent: £ 74.99 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Address: Hawthorne Avenue, Mickley, Alfreton, Derbyshire DE55 6GB Ref: 1107535 Type: 3 Bed House Rent: £ 94.34 -

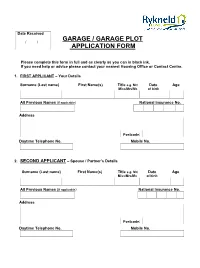

Garage Application Form

Date Received / / GARAGE / GARAGE PLOT APPLICATION FORM Please complete this form in full and as clearly as you can in black ink. If you need help or advice please contact your nearest Housing Office or Contact Centre. 1. FIRST APPLICANT – Your Details Surname (Last name) First Name(s) Title e.g. Mr/ Date Age Miss/Mrs/Ms of birth All Previous Names (If applicable) National Insurance No. Address Postcode: Daytime Telephone No. Mobile No. 2. SECOND APPLICANT – Spouse / Partner’s Details Surname (Last name) First Name(s) Title e.g. Mr/ Date Age Miss/Mrs/Ms of birth All Previous Names (If applicable) National Insurance No. Address Postcode: Daytime Telephone No. Mobile No. 3. At Your Present Address Are you? Is your joint applicant? Council Tenant Owner Occupier Lodger Tied Tenant Housing Association Private Landlord 4. Do you currently rent or have you ever rented a garage Yes: No: from North East Derbyshire District Council 5. Do you currently rent or have you ever rented a garage plot Yes: No: from North East Derbyshire District Council If you answered No to questions 5 or 6, please go to Question 8 6. Where is/was the site situated? 7. If you are applying for an additional Garage / Garage Plot please state reason(s) why? 8. Do you require a Garage? Yes: No: 9. Do you require a Garage Plot? Yes: No: Eligibility to Register • Have you committed a criminal offence or engaged in criminal or anti social activity? Yes No If Yes please supply details: • Do you owe this council or any other landlord current rent arrears, former tenant’s arrears or any sundry debts? Yes No If Yes please supply details: • Are you, or have you been in the past, subject to any formal notice to seek possession of your home? Yes No If Yes please supply details: I / we* certify that the whole of the particulars given in this Application for a Garage/Garage Plot are true. -

Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012 Reg12

Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012 Reg12 Statement of Consultation SUCCESSFUL PLACES: A GUIDE TO SUSTAINABLE LAYOUT AND DESIGN SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING DOCUMENT Undertaken by Chesterfield Borough Council also on behalf and in conjunction with: July 2013 1 Contents 1. Introduction Background to the Project About Successful Places What is consultation statement? The Project Group 2. Initial Consultation on the Scope of the Draft SPD Who was consulted and how? Key issues raised and how they were addressed 3. Peer Review Workshop What did we do? Who was involved? What were the outcomes? 4. Internal Consultations What did we do and what were the outcomes? 5. Strategic Environmental Assessment and Habitats Regulation Assessment What is a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Is a SEA required? What is a Habitats Regulation Assessment (HRA) Is a HRA required? Who was consulted? 6. Formal consultation on the draft SPD Who did we consult? How did we consult? What happened next? Appendices Appendix 1: Press Notice Appendix 2: List of Consultees Appendix 3: Table Detailed Comments and Responses Appendix 4: Questionnaire Appendix 5: Public Consultation Feedback Charts 2 1. Introduction Background to the Project The project was originally conceived in 2006 with the aim of developing new planning guidance on residential design that would support the local plan design policies of the participating Council’s. Bolsover District Council, Chesterfield Borough Council and North East Derbyshire District Council shared an Urban Design Officer in a joint role, to provide design expertise to each local authority and who was assigned to take the project forward. -

Skidmore Lead Miners of Derbyshire, and Their Descendants 1600-1915

Skidmore Lead Miners of Derbyshire & their descendants 1600-1915 Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study 2015 www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com [email protected] SKIDMORE LEAD MINERS OF DERBYSHIRE, AND THEIR DESCENDANTS 1600-1915 by Linda Moffatt 2nd edition by Linda Moffatt© March 2016 1st edition by Linda Moffatt© 2015 This is a work in progress. The author is pleased to be informed of errors and omissions, alternative interpretations of the early families, additional information for consideration for future updates. She can be contacted at [email protected] DATES Prior to 1752 the year began on 25 March (Lady Day). In order to avoid confusion, a date which in the modern calendar would be written 2 February 1714 is written 2 February 1713/4 - i.e. the baptism, marriage or burial occurred in the 3 months (January, February and the first 3 weeks of March) of 1713 which 'rolled over' into what in a modern calendar would be 1714. Civil registration was introduced in England and Wales in 1837 and records were archived quarterly; hence, for example, 'born in 1840Q1' the author here uses to mean that the birth took place in January, February or March of 1840. Where only a baptism date is given for an individual born after 1837, assume the birth was registered in the same quarter. BIRTHS, MARRIAGES AND DEATHS Databases of all known Skidmore and Scudamore bmds can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com PROBATE A list of all known Skidmore and Scudamore wills - many with full transcription or an abstract of its contents - can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com in the file Skidmore/Scudamore One-Name Study Probate. -

Helping Hand for Issue Kenning Good Neighbour Winners Page 3 Park Page 3

35th Edition • April 2016 HHoming In cosots 25p a compy to print in gin In this Helping hand for issue Kenning Good Neighbour Winners page 3 Park page 3 New Look Neighbourhood Services page 8-9 Win £1,000 in vouchers! page 20 Dear Reader ell done to the In this issue we’ve included winners of our information about important 2015 Good changes to the way we deliver Estates Walkabout our Neighbourhood Services. We Neighbour of W have introduced a new team of opportunity to win £1,000 in the Year Awards! Housing and Support Officers and shopping vouchers with our We were delighted to present Managers for each area – so you Direct Debit prize draw. the prizes to our worthy winner will notice a change in faces. Anyone setting up a new Direct Lorraine Jones, who received The Housing and Support staff Debit, between now and the end £150 in shopping vouchers. Our will continue to deliver the of September will be fantastic runners-up Steve Jones normal estate and tenancy automatically entered into a and Stuart Brown received £75 in management services, but they national prize draw for one of vouchers. will also be responsible for five top prizes. Direct Debit is Going the extra mile for a carrying out some of the the easiest and quickest way to neighbour, or a local community, independent living service duties. pay your rent – and our staff will can make such a big difference To find out more about the help you set one up. and is definitely something worth changes and the staff for your To find out more about the celebrating. -

Land at Blacksmith's Arms

Land off North Road, Glossop Education Impact Assessment Report v1-4 (Initial Research Feedback) for Gladman Developments 12th June 2013 Report by Oliver Nicholson EPDS Consultants Conifers House Blounts Court Road Peppard Common Henley-on-Thames RG9 5HB 0118 978 0091 www.epds-consultants.co.uk 1. Introduction 1.1.1. EPDS Consultants has been asked to consider the proposed development for its likely impact on schools in the local area. 1.2. Report Purpose & Scope 1.2.1. The purpose of this report is to act as a principle point of reference for future discussions with the relevant local authority to assist in the negotiation of potential education-specific Section 106 agreements pertaining to this site. This initial report includes an analysis of the development with regards to its likely impact on local primary and secondary school places. 1.3. Intended Audience 1.3.1. The intended audience is the client, Gladman Developments, and may be shared with other interested parties, such as the local authority(ies) and schools in the area local to the proposed development. 1.4. Research Sources 1.4.1. The contents of this initial report are based on publicly available information, including relevant data from central government and the local authority. 1.5. Further Research & Analysis 1.5.1. Further research may be conducted after this initial report, if required by the client, to include a deeper analysis of the local position regarding education provision. This activity may include negotiation with the relevant local authority and the possible submission of Freedom of Information requests if required. -

Peak District National Park Visitor Survey 2005

PEAK DISTRICT NATIONAL PARK VISITOR SURVEY 2005 Performance Review and Research Service www.peakdistrict.gov.uk Peak District National Park Authority Visitor Survey 2005 Member of the Association of National Park Authorities (ANPA) Aldern House Baslow Road Bakewell Derbyshire DE45 1AE Tel: (01629) 816 200 Text: (01629) 816 319 Fax: (01629) 816 310 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.peakdistrict.gov.uk Your comments and views on this Report are welcomed. Comments and enquiries can be directed to Sonia Davies, Research Officer on 01629 816 242. This report is accessible from our website, located under ‘publications’. We are happy to provide this information in alternative formats on request where reasonable. ii Acknowledgements Grateful thanks to Chatsworth House Estate for allowing us to survey within their grounds; Moors for the Future Project for their contribution towards this survey; and all the casual staff, rangers and office based staff in the Peak District National Park Authority who have helped towards the collection and collation of the information used for this report. iii Contents Page 1. Introduction 1.1 The Peak District National Park 1 1.2 Background to the survey 1 2. Methodology 2.1 Background to methodology 2 2.2 Location 2 2.3 Dates 3 2.4 Logistics 3 3. Results: 3.1 Number of people 4 3.2 Response rate and confidence limits 4 3.3 Age 7 3.4 Gender 8 3.5 Ethnicity 9 3.6 Economic Activity 11 3.7 Mobility 13 3.8 Group Size 14 3.9 Group Type 14 3.10 Groups with children 16 3.11 Groups with disability 17 3.12 -

HOLYMOORSIDE and WALTON PARISH Submission Draft Neighbourhood Plan 2016 -2033

HOLYMOORSIDE AND WALTON PARISH Submission Draft Neighbourhood Plan 2016 -2033 Submission Draft Neighbourhood Plan Consultation Contents Public Notice of Submission of the Neighbourhood Plan Parish Council Submission Letter Holymoorside and Walton Neighbourhood Plan Neighbourhood Plan Map Basic Conditions Statement Consultation Statement Strategic Environmental Assessment and Habitats Regulation Assessment Screening Report Holymoorside and Walton Parish Council Meeting 4th April 2017 Background The Holymoorside and Walton Neighbourhood Development Plan has been written by the Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group and approved by the Parish Council. It proposes a number of policies on housing provision, employment, the environment and community facilities. The Plan underwent consultation for 6 weeks ending on 8th March 2016. Comments made to the Parish Council from that consultation helped inform changes to the document now submitted to North East Derbyshire District Council. The Plan is subject to a period of consultation for 6 weeks, from 26th May to 7th July Details of where the Plan is deposited, how to comment, contact details, and subsequent stages of the process are on the Public Notice on the next sheet. Helen Fairfax, Planning Policy Manager, North East Derbyshire District Council. i ii North East Derbyshire District Council HOLYMOORSIDE AND WALTON NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN SUBMISSION OF NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN PROPOSAL Holymoorside and Walton Parish Council has submitted a Neighbourhood Plan proposal under the Town and Country Planning Neighbourhood Planning (General) Regulations 2012 (reg. 15). The Plan sets out a vision for the Parish and establishes the type of development needed to help sustain the community. If made, it will become part of the development plan for land use and development proposals within the Parish until 2033. -

Faith in Derbyshire

FaithinDerbyshire Derby Diocesan Council for Social Responsibility Derby Church House Full Street Derby DE1 3DR Telephone: 01332 388684 email: [email protected] fax: 01332 292969 www.derby.anglican.org Working towards a better Derbyshire; faith based contribution FOREWORD I am delighted to be among those acknowledging the significance of this report. Generally speaking, people of faith are not inclined to blow their own trumpets. This report in its calm and methodical way, simply shows the significant work quietly going on through the buildings and individuals making up our faith communities. Such service to the community is offered out of personal commitment. At the same time, it also deserves acknowledgment and support from those in a position to allocate resources, because grants to faith communities are a reliable and cost effective way of delivering practical help to those who need it. Partnership gets results. This report shows what people of faith are offering. With more partners, more can be offered. David Hawtin Bishop of Repton and Convenor of the Derbyshire Church and Society Forum I am especially pleased that every effort has been taken to make this research fully ecumenical in nature, investigating the work done by churches of so many different denominations: this makes these results of even greater significance to all concerned. I hope that a consequence of churches collaborating in this effort will be an increased partnership across the denominations in the future. Throughout their history Churches have been involved in their communities and this continues today. In the future this involvement is likely to result in increasing partnerships, not only with each other but also with other agencies and community groups. -

12-5-2014 1.1Km Somersall Lane to Greendale Avenue

Public Agenda Item No. 4 DERBYSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL REGULATORY – PLANNING COMMITTEE 12 May 2014 Report of the Strategic Director – Economy, Transport and Environment 2 PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION OF A 1.1 KILOMETRES GREENWAY BETWEEN SOMERSALL LANE, CHESTERFIELD AND GREENDALE AVENUE, HOLYMOORSIDE APPLICANT: DERBYSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL CODE NOS: CD4/0413/3 & CD2/0413/3 4.2485.3 & 2.713.3 Introductory Summary This application proposes the construction of a 1.1 km greenway located on the existing Public Rights of Way linking Somersall Lane to Holymoorside. The upgrading of the existing footpaths would form part of a wider initiative to create a multi-user trail linking Chesterfield Railway station with Holymoorside. I do not consider that the proposal would be harmful to the open character of the Green Belt and it would bring social and community benefits to the area especially with the aim of creating a safe route for pupils to walk and cycle to and from school. The potential Impact of the development on the ecology and wider landscape and visual character of the area could be adequately controlled by condition. However the potential impacts of the development on highway safety and the character and appearance of the Somersall Lane Conservation Area have not been satisfactory resolved and I therefore consider that the development would be unacceptable impact on those grounds. The application is therefore recommended for refusal. (1) Purpose of the Report To enable the Committee to determine the application. (2) Information and Analysis This application proposes the construction of approximately 1.1 linear kilometres (km) of multi-user greenway trail between Somersall Lane, Chesterfield and Greendale Avenue, Holymoorside. -

X70 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

X70 bus time schedule & line map X70 Bakewell - Chesterƒeld View In Website Mode The X70 bus line (Bakewell - Chesterƒeld) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bakewell: 8:05 AM - 5:35 PM (2) Buxton: 9:20 AM - 3:15 PM (3) Chesterƒeld: 7:10 AM - 5:03 PM (4) Middleton by Youlgreave: 4:35 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest X70 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next X70 bus arriving. Direction: Bakewell X70 bus Time Schedule 44 stops Bakewell Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:05 AM - 4:25 PM Monday 8:05 AM - 5:35 PM New Beetwell Street, Chesterƒeld (B12) Pavements Shopping Centre Car Park Bridge, Chesterƒeld Tuesday 8:05 AM - 5:35 PM West Bars, Chesterƒeld Wednesday 8:05 AM - 5:35 PM 1 Future Walk, Chesterƒeld Thursday 8:05 AM - 5:35 PM Wheatbridge Road, Chesterƒeld Friday 8:05 AM - 5:35 PM Wheatbridge Road, Chesterƒeld Saturday 8:20 AM - 5:35 PM Tramway Tavern, Brampton Chatsworth Road, Chesterƒeld Barker Lane, Brampton A619, Chesterƒeld X70 bus Info Direction: Bakewell Walton Road End, Brampton Stops: 44 Chatsworth Road, Chesterƒeld Trip Duration: 40 min Line Summary: New Beetwell Street, Chesterƒeld Heaton Street, Brampton (B12), West Bars, Chesterƒeld, Wheatbridge Road, 422 Chatsworth Road, Chesterƒeld Chesterƒeld, Tramway Tavern, Brampton, Barker Lane, Brampton, Walton Road End, Brampton, Vincent Crescent, Brampton Heaton Street, Brampton, Vincent Crescent, Brampton, Brookƒeld Community School, Brookside, Brookƒeld Community School, Brookside Brookƒeld Avenue, Brookside, Brookside -

THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION for ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW of NORTH EAST DERBYSHIRE Final Recommendations for Ward Bo

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF NORTH EAST DERBYSHIRE Final recommendations for ward boundaries in the district of North East Derbyshire August 2017 Sheet 1 of 1 This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2017. Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. K KILLAMARSH EAST RIDGEWAY & MARSH LANE KILLAMARSH CP KILLAMARSH WEST F I B E ECKINGTON NORTH A COAL ASTON ECKINGTON CP DRONFIELD WOODHOUSE H C DRONFIELD CP DRONFIELD NORTH J GOSFORTH VALLEY L ECKINGTON SOUTH & RENISHAW G D DRONFIELD SOUTH UNSTONE UNSTONE CP HOLMESFIELD CP BARLOW & HOLMESFIELD KEY TO PARISH WARDS BARLOW CP DRONFIELD CP A BOWSHAW B COAL ASTON C DRONFIELD NORTH D DRONFIELD SOUTH E DRONFIELD WOODHOUSE F DYCHE G GOSFORTH VALLEY H SUMMERFIELD ECKINGTON CP I ECKINGTON NORTH J ECKINGTON SOUTH K MARSH LANE, RIDGEWAY & TROWAY L RENISHAW & SPINKHILL NORTH WINGFIELD CP M CENTRAL BRAMPTON CP N EAST O WEST WINGERWORTH CP P ADLINGTON Q HARDWICK WOOD BRAMPTON & WALTON R LONGEDGE S WINGERWORTH T WOODTHORPE CALOW CP SUTTON SUTTON CUM DUCKMANTON CP HOLYMOORSIDE AND WALTON CP GRASSMOOR GRASSMOOR, TEMPLE S HASLAND AND NORMANTON