THE ERECT of the OAK HILT FUNGUS UPON OAK HOOD DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forestry Materials Forest Types and Treatments

-- - Forestry Materials Forest Types and Treatments mericans are looking to their forests today for more benefits than r ·~~.'~;:_~B~:;. A ever before-recreation, watershed protection, wildlife, timber, "'--;':r: .";'C: wilderness. Foresters are often able to enhance production of these bene- fits. This book features forestry techniques that are helping to achieve .,;~~.~...t& the American dream for the forest. , ~- ,.- The story is for landolVners, which means it is for everyone. Millions . .~: of Americans own individual tracts of woodland, many have shares in companies that manage forests, and all OWII the public lands managed by government agencies. The forestry profession exists to help all these landowners obtain the benefits they want from forests; but forests have limits. Like all living things, trees are restricted in what they can do and where they can exist. A tree that needs well-drained soil cannot thrive in a marsh. If seeds re- quire bare soil for germination, no amount of urging will get a seedling established on a pile of leaves. The fOllOwing pages describe th.: ways in which stands of trees can be grown under commonly Occllrring forest conditions ill the United States. Originating, growing, and tending stands of trees is called silvicllllllr~ \ I, 'R"7'" -, l'l;l.f\ .. (silva is the Latin word for forest). Without exaggeration, silviculture is the heartbeat of forestry. It is essential when humans wish to manage the forests-to accelerate the production or wildlife, timber, forage, or to in- / crease recreation and watershed values. Of course, some benerits- t • wilderness, a prime example-require that trees be left alone to pursue their' OWII destiny. -

A Treemendous Educator Guide

A TREEmendous Educator Guide Throughout 2011, we invite you to join us in shining a deserving spotlight on some of Earth’s most important, iconic, and heroic organisms: trees. To strengthen efforts to conserve and sustainably manage trees and forests worldwide, the United Nations has declared 2011 as the International Year of Forests. Their declaration provides an excellent platform to increase awareness of the connections between healthy forests, ecosystems, people, and economies and provides us all with an opportunity to become more aware, more inspired, and more committed to act. Today, more than 8,000 tree species—about 10 percent of the world’s total—are threatened with extinction, mostly driven by habitat destruction or overharvesting. Global climate change will certainly cause this number to increase significantly in the years to come. Here at the Garden, we care for many individual at-risk trees (representing 48 species) within our diverse, global collection. Many of these species come from areas of the world where the Garden is working to restore forest ecosystems and the trees in them. Overall, we have nearly 6,000 individual trees in our main Garden, some dating from the time of founder Henry Shaw. Thousands more trees thrive at nearby Shaw Nature Reserve, as part of the Garden’s commitment to native habitat preservation, conservation, and restoration. Regardless of where endangered trees are found—close to home or around the world—their survival requires action by all of us. The Great St. Louis Tree Hunt of 2011 is one such action, encouraging as many people as possible to get out and get connected with the spectacular trees of our region. -

Advanced Timber Bridge Inspection

Advanced Timber Bridge Inspection Field Manual for Inspection of Minnesota Timber Bridges Natural Resources Research Institute [This page intentionally left blank] ii Acknowledgements Thank you to the following sponsors and project participants for their valuable input in the production of this document. Primary Lead Authors Brian Brashaw, University of Minnesota Duluth Natural Resources Research Institute James Wacker, USDA Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory Robert J. Ross, USDA Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory Funding Sponsors: Minnesota Local Road Research Board (LRRB), Contract 99008 WO 62 Iowa Highway Research Board (IHRB) Project Team: University of Minnesota Duluth Natural Resources Research Institute Minnesota Department of Transportation Bridge Office Minnesota Department of Transportation Research Office Iowa State University, Bridge Engineering Center USDA Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory HDR, Inc. Technical Advisory Panel: Project Leaders: Brian Brashaw, University of Minnesota Duluth Natural Resources Research Institute (NRRI) David Conkel, Minnesota Department of Transportation, State Aid Travis Hosteng, Iowa State University Bridge Engineering Center Chris Werner, HDR Engineering, Inc. James Wacker, USDA Forest Products Laboratory Committee Members: Ahmad Abu-Hawash, Iowa Department of Transportation, Bridges and Structures Matthew Hemmila, St. Louis County (Minnesota) Greg Isakson, Goodhue County (Minnesota) Art Johnston, USDA Forest Service (retired) Brian Keierleber, Buchanan County (Iowa) -

Common Forestry Terms for the Forest Landowner

ALABAMA A&M AND AUBURN UNIVERSITIES Common Forestry Terms for the Forest ANR-1373 Landowner ithout a basic understanding of forestry agroforestry terms, it can be difficult to communicate The practice of growing trees and agricultural or W with foresters or buyers of forestland or horticultural crops on the same site. timber. Being well versed in forestry terminology can help landowners feel confident when making • alley cropping management decisions or selling their timber. This The practice of growing crops between rows of glossary is a tool for landowners seeking to define planted trees. ownership objectives, develop management plans, improve their timber stands, or conduct a timber sale. • conservation buffers Using a forestry consultant is highly recommended, The practice of growing trees in rows to alter wind and knowing these terms can help landowners better flow and protect crops, reduce erosion, improve communicate with foresters and understand various irrigation efficiency, improve water quality, and forestry processes. provide habitat for wildlife. • forest farming Forest Management The practice of cultivating or collecting specialty afforestation forest products in the forest environment. Growing trees on land where there were none. • silvopasture Cost-share programs usually require that the land has The practice of grazing livestock among not been in forest for at least several decades. forest trees. ARCHIVE Silvopasture (photo credit: MediaAssociates) www.aces.edu Windrow (Photo credit: Janice Dyer) best management practices (BMPs) overtopping Guidelines to minimize negative impacts on the When trees of undesirable species grow faster than environment, such as soil erosion and water pollution, those of the target species, blocking sunlight and before, during, and after a timber harvest or other slowing their growth. -

A Glossary of Common Forestry Terms

W 428 A Glossary of Common Forestry Terms A Glossary of Common Forestry Terms David Mercker, Extension Forester University of Tennessee acre artificial regeneration A land area of 43,560 square feet. An acre can take any shape. If square in shape, it would measure Revegetating an area by planting seedlings or approximately 209 feet per side. broadcasting seeds rather than allowing for natural regeneration. advance reproduction aspect Young trees that are already established in the understory before a timber harvest. The compass direction that a forest slope faces. afforestation bareroot seedlings Establishing a new forest onto land that was formerly Small seedlings that are nursery grown and then lifted not forested; for instance, converting row crop land without having the soil attached. into a forest plantation. AGE CLASS (Cohort) The intervals into which the range of tree ages are grouped, originating from a natural event or human- induced activity. even-aged A stand in which little difference in age class exists among the majority of the trees, normally no more than 20 percent of the final rotation age. uneven-aged A stand with significant differences in tree age classes, usually three or more, and can be basal area (BA) either uniformly mixed or mixed in small groups. A measurement used to help estimate forest stocking. Basal area is the cross-sectional surface area (in two-aged square feet) of a standing tree’s bole measured at breast height (4.5 feet above ground). The basal area A stand having two distinct age classes, each of a tree 14 inches in diameter at breast height (DBH) having originated from separate events is approximately 1 square foot, while an 8-inch DBH or disturbances. -

Florida Forest Service James R. Karels, State Forester

Florida Forest Service James R. Karels, State Forester The forest needs of Florida’s citizens are much greater than many realize, often impacting our lives in ways that we may not always see. It is estimated that the average person utilizes 40 products a day that are derived from the forest. This not only includes the obvious products such as lumber and paper, but items such as toothpaste, ice cream, film, cellophane, tape, adhesives, and enhancements for many of the foods we eat and drink. There are well over 5,000 different products that come from forests. Of course, there are many other benefits we derive from forests, such as clean air, clean water, recreation and an enhanced environment. Currently the forest industry is the leading agricultural industry in Florida and second only to tourism in total impact on the state’s economy. The timber industry also provides numerous jobs, outdoor recreation opportunities for millions of visitors each year. Forestry is about balancing the ecological, social and economic needs of our state. Educating our citizens about proper forest management practices will help ensure that forests will be healthy and that the forest industry remains a viable commodity for future generations. The purpose of this book is to reach out to our youth to teach them good forestry practices. Jim Karels State Forester, Florida Forest Service Table of Contents For the Teacher, Sunshine State Standards . ii Part One: Introduction . 1 Introduction . 3 History of Florida’s Forests . 4 Forest Communities . 7 Succession . 8 The Tree . 8 Dendrology . 10 Part Two: Forest Management . -

Tree Cookies & Logging Equipment Talks at Popcorn Break/Lunch

Tree Cookies & Logging Equipment talks at popcorn break/lunch This is a 10 - 15 minute lesson that should be done during their popcorn and/or lunch break. There will be either a feller buncher OR a skidder at Wood Magic depending on the location. Contact Beth Foley before the program to find out which one. Blanchard Machinery loans us this brand new equipment off their sale floor for FREE. Please do not let students climb on equipment. Talks seemed to work better at popcorn break as kids were done more quickly; therefore, having more free time than at lunch. The two foresters assigned to this station work well as a team, with one being the lead speaker on each topic; Tree Cookies and Logging Equipment. Lunch time worked well for a live demo of an increment borer and kids were really interested in seeing the increment borer at work and the actual increment cores. Materials: increment borer, tree cookie examples showing varying growth rates in the rings, forestry equipment, 4 signs depicting equipment and logging operations Tree Cookies Hello. How are you this morning? I’m____ and this is_____. A forester is someone who has learned how trees grow, how to measure them, take care of them and manage them for use. Hold up large tree cookie. This is called a tree cookie. It was cut from the end of a log from a tree that was being harvested. Can anyone tell me how you can tell how old this tree was? Interact with kids. That’s right, you count the rings. -

Forestry Related Careers

Forestry in the Classroom Series Forestry Related Careers An Educational Series for Grades 4, 5 and 6 Tree-Related Careers Some jobs are obviously related to forests and trees. You might think of forest rangers, lumberjacks, and Christmas tree sellers. But the creation and management of forests, timber, parks, and tree and wood products requires people with a wide variety of skills to work together. As you’ll see from the following list, many people combine their love of the woods with other interests and abilities to do their part for the trees. Silviculturist ACCOUNTANT All accountants must adhere Like their counterparts the urban foresters, silvicul- to generally accepted accounting turists devote their careers to the cultivation and care principles. But because trees are of forests. Silviculturists look at stands of trees cover- living organisms, their value is in ing between 10 and 30 acres and determine the vol- constant flux and communicating ume for commercial output, taking into account the the worth of forest assets at true factors of disease, soil, water, climate, and diversity market value is a real challenge. of species. To enjoy this career, you need to like working in the woods with maps and compasses. Garden Consultant Many landscape and garden designers have transformed a personal passion for gardening into a career that sustains them. Practical experience, a wealth of knowledge, and an eye for beauty are the only requisites for a career as a garden designer, although an ability to market, network, and establish a client referral base is essential to a steady career. -

Forestry CD Activity Guide Cover, You Will See a Forester Demonstrating the Correct Technique to Determine DBH with a Biltmore Stick

chapter 8/27/56 9:33 AM Page 2 Source: Project Learning Tree K-8 Activity Guide: page 243 2 chapter 8/27/56 9:33 AM Page 3 TOOLS USED IN FORESTRY Biltmore stick – Clinometer – Diameter Tape – Increment Borer – Wedge Prism Throughout history, the need for measurement has been a necessity for each civilization. In commerce, trade, and other contacts between societies, the need for a common frame of reference became essential to bring harmony to interactions. The universal acceptance of given units of measurement resulted in a common ground, and avoided dissension and misunderstanding. In the early evolvement of standards, arbitrary and simplified references were used. In Biblical times, the no longer familiar cubit was an often-used measurement. It was defined as the distance from the elbow to a person’s middle finger. Inches were determined by the width of a person’s thumb. According to the World Book Encyclopedia, “The foot measurement began in ancient times based on the length of the human foot. By the Middle Ages, the foot as defined by different European countries ranged from 10 to 20 inches. In 1305, England set the foot equal to 12 inches, where 1 inch equaled the length of 3 grains of barley dry and round.”1 [King Edward I (Longshanks), son of Henry III, ruled from 1272–1307.] Weight continues to be determined in Britain by a unit of 14 pounds called a “stone.” The origin of this is, of course, an early stone selected as the arbitrary unit. The flaw in this system is apparent; the differences in items selected as standards would vary. -

A Manual and Tutorial for the Proper Use of an Increment Borer

TREE -RING RESEARCH, Vol. 59(2), 2003, pp. 63 -79 A MANUAL AND TUTORIAL FOR THE PROPER USE OF AN INCREMENT BORER HENRI D. GRISSINO -MAYER Laboratory of Tree -Ring Science Department of Geography University of Tennessee Knoxville, TN 37996, USA ABSTRACT An increment borer is the primary tool used to collect samples for dendrochronological analyses. These are precision instruments and users should be trained in their proper use, care, and maintenance. In this paper, I describe the various parts of an increment borer and how to keep these in working condition. I provide details on how to sharpen an increment borer, properly core a tree, check for core compression ( "jamming "), extract the core, and store the core for transport. I provide tips on how to clear a jammed borer and remove a borer stuck in a tree. An important topic concerns the effects of boring on trees. The majority of studies indicate that conifers are minimally affected by both fungal decay and discoloration, whereas certain hardwood species can sustain major internal damage. Plugging the holes created by coring is unnecessary. Keywords: increment borers, increment borer maintenance, damage from increment borers, field methods. INTRODUCTION cesses (Yamaguchi et al.1997; Gärtner et al. 2001). The increment borer was developed in Germany Information on past environments gained from ca. 1855 (Pressler 1866), and has changed littleliving trees is often extended back in time using since its original design (Schweingruber 2001). In-tree rings from dead trees (e.g. Grissino -Mayer crement borers are used to extract cores from liv- 1996), including downed logs, snags (standing ing and dead trees for analysis of growth trendsdead trees), remnant wood, and buried/exposed based on inspection of the tree's ring patterns. -

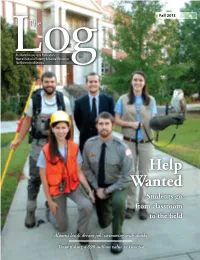

Help Wanted Students Go from Classroom to the Field

Fall 2013 Help Wanted Students go from classroom to the field Alumni lands dream job: swimming with sharks Trout fishing a $90 million value to Georgia A Message from the Dean Plum Creek golf tournament a hole in one for Warnell Plum Creek hosted its fifth annual charity golf tournament this fall, raising a significant windfall for the Warnell School. This annual fundraiser helps financially support student and faculty services and comes from one of Comments, Congrats Warnell’s most enthusiastic supporters. The Plum Creek Charity Golf Tournament is a popular annual out- ing held at the Georgia Club just outside of Athens, drawing alumni and Warnell supporters from across the country. The next tournament is set for Sept. 26, 2014. The 2013 tournament’s support came at a critical time and Goodbyes: for our programs, said Dean Mike Clutter. “This year we had a perfect fall day in the Piedmont,” he said. “For the first time, thanks to Plum Creek and our sponsors, we raised more than $100,000 for the Warnell School. We are looking to the future These funds are used to support our undergraduate and graduate programs in a wide variety of ways — through scholarships, assistantships and funds for research and teaching activities. We continue to be overwhelmed by the support for our programs.” We need your input. Special Thanks to our Tournament Co-hosts: Over the next several months Warnell will be soliciting comments on our programs as we develop our next 10-year strategic plan. This effort is the primary document that Warnell uses to shape its programs and focus resources on future directions for the school. -

Basic Forest Inventory Techniques for Family Forest Owners

Basic Forest Inventory Techniques for Family Forest Owners "1"$*'*$/035)8&45&95&/4*0/16#-*$"5*0/t1/8 WBTIJOHUPO4UBUF6OJWFSTJUZt0SFHPO4UBUF6OJWFSTJUZt6OJWFSTJUZPG*EBIP Basic Forest Inventory Techniques for Family Forest Owners Table of Contents Introduction .....................................................................................................................................................................1 How to use this manual .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1: Mapping your forest ............................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 2: Introduction to plot sampling ............................................................................................................ 9 Chapter 3: Locating plots on the ground ...........................................................................................................13 Chapter 4: Establishing fixed-radius plots ..........................................................................................................17 Chapter 5: Establishing variable plots (for advanced users) ........................................................................20 Chapter 6: Measuring trees ......................................................................................................................................23 Chapter 7: Basic inventory calculations ..............................................................................................................31