2.0 the Economic Benefits of Sustainable Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix B – Eco-Charrette Report

Appendix B – Eco-Charrette Report 2010 Facility Master Plan Factoria Recycling and Transfer Station November 2010 2010 Facility Master Plan Factoria Recycling and Transfer Station November 2010 Appendix B‐1: Factoria Recycling and Transfer Station ‐ Eco‐Charrette – Final Report. June 24, 2010. Prepared for King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks‐‐ Solid Waste Division. HDR Engineering, Inc. Appendix B‐2: Initial Guidance from the Salmon‐Safe Assessment Team regarding The Factoria Recycling and Transfer Station – Site Design Evaluation. July 15, 2010. Salmon‐Safe, Inc. Appendix B‐1: Factoria Recycling and Transfer Station ‐ Eco‐Charrette – Final Report. June 24, 2010. Prepared for King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks‐‐ Solid Waste Division. HDR Engineering, Inc. Table of Contents PART 1: ECO‐CHARRETTE...................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction and Purpose ......................................................................................................................... 1 Project Background and Setting ................................................................................................................ 1 Day 1. Introduction to the Sustainable Design Process ........................................................................... 3 Day 2: LEED Scorecard Review ................................................................................................................. 4 The LEED Green Building Certification -

BEYOND SUSTAINABILITY THROUGH REGENERATIVE ARCHITECTURE Regenerative Urban Landscapes

BEYOND SUSTAINABILITY THROUGH REGENERATIVE ARCHITECTURE Regenerative Urban Landscapes SAM NEMATI Thesis Report Master of Fine Arts in Architecture and Urban Design Year 5 Studio 12 Tutors: Alejandro Haiek, Carl-Johan Vesterlund, Andrew Bellfild, Tom Dobson Spring 2020 Umeå School of Architecture Umeå University 4640 Words Sam Nemati Thesis Report Spring 2020 Contents Table of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................ 5 CHAPTER 1: Beyond sustainability through regenerative architecture ..................................................... 6 1. Climate Change and Regenerative Architecture ................................................................................... 6 2. Regenerative Architecture in Practice .................................................................................................. 7 2.1. Case Study: Playa Viva, Mexico (2009) .............................................................................................. 8 3. Regenerative -

Multifarious Approaches to Attain Sustainable Fashion

Dr. Nidhi L Sharda is an Associate Professor in the Department of Multifarious Approaches to Knitwear Design at National Institute of Fashion Technology, Bangalore. In Attain Sustainable Fashion the decade and a half of her profes- sional life, she has extensively utilized Dr. Nidhi L. Sharda, Mr. Mohan Kumar VK her applied research which focuses Dept. of Knitwear Design, National Institute of Fashion Technology, Bangalore on the area of apparel and textile [email protected] design. Her applied research focuses on the area of textile and costumes Abstract with research experience in the field Fashion is a huge industry and affects environmental, economic and social system in of natural dyes, sustainable fashion, many ways. Exploitation of resources for ever changing trends in fashion is immense clothing and craft. and providing these demands put enormous pressure on the environment. In such a situation sustainable practices in every human activity has become important and fashion Mr. Mohan Kumar VK is an Assistant is not less affected by this drive. Fashion professionals have to play major role to Professor & Centre Coordinator of the inculcate the concept of sustainable fashion with responsibility in their product line. It Department of Knitwear Design at is important that while designing, designer should understand the benefits of sustain- National Institute of Fashion able operation starting with concept development level. In this paper design solutions Technology, Bangalore. He has 9 years for sustainable fashion are inferred in a design school scenario. The main idea to do so of teaching experience in NIFT. As a is to develop more sensible and responsible designs, which can be better solutions for designer, NIFT being his Alma Mater, sustainable fashion. -

A Guide to Environmentally Sustainable Landscape Architecture Products

A Guide to Environmentally Sustainable Landscape Architecture Products jonite.com/a-guide-to-environmentally-sustainable-and-long-lasting-landscape-architecture-products May 23, 2019 Landscape architects play an essential role in creating design interventions to ensure environmental sustainability. As we’ve explained in our other post on architectural trends that are here to stay (link), sustainability and climate adaptation strategies have not only been increasingly in the focus, but is here to stay. Sustainable architecture aims to incorporate elements of green design into various parts of the building. The main goal is to strike a beautiful harmony between green life and architecture to preserve nature and improve the quality of living. Green buildings are designed in a way to be built in a way that reduces harmful impact on the environment. What is environmentally sustainable design? 1/13 Environmentally sustainable design (or environmentally-conscious design, eco-design) is the philosophy of designing physical objects, the built environment and services to comply with the principles of ecological sustainability. Its core idea is to eliminate wastefulness and minimise environmental impact through architecture design. There are some common principles in sustainable design that most designers take into consideration when scoping out their design projects. They include the following: Choosing low-impact materials: These come in the form of choosing products that have high recycled content incorporated in the manufacturing process. Also, designers may choose materials that are locally sourced to reduce the carbon footprint of transporting materials to the project site. Choosing energy-efficient materials: Designers may also take the time to understand the material’s basic manufacturing processes and make their choice based on the energy involved in producing their selected materials. -

Meaningful Urban Design: Teleological/Catalytic/Relevant

Journal ofUrban Design,Vol. 7, No. 1, 35– 58, 2002 Meaningful Urban Design: Teleological/Catalytic/Relevant ASEEM INAM ABSTRACT Thepaper begins with a critique ofcontemporary urban design:the eldof urban designis vague because it isan ambiguousamalgam of several disciplines, includingarchitecture, landscapearchitecture, urban planningand civil engineering; it issuper cial because itisobsessedwith impressions and aesthetics ofphysical form; and it ispractised as an extensionof architecture, whichoften impliesan exaggerated emphasison theend product. The paper then proposesa meaningful(i.e. truly consequential to improvedquality of life) approach to urban design,which consists of: beingteleological (i.e. driven by purposes rather than de ned by conventional disci- plines);being catalytic (i.e. generating or contributing to long-term socio-economic developmentprocesses); andbeing relevant (i.e. grounded in rst causes andpertinent humanvalues). The argument isillustratedwith a number ofcase studiesof exemplary urban designers,such asMichael Pyatok and Henri Ciriani,and urban designprojects, such asHorton Plazaand Aranya Nagar, from around the world. The paper concludes withan outlineof future directionsin urban design,including criteria for successful urban designprojects (e.g. striking aesthetics, convenient function andlong-term impact) anda proposedpedagogical approach (e.g. interdisciplinary, in-depth and problem-driven). Provocations In the earlypart of 1998,two provocative urban design eventsoccurred at the Universityof Michigan in Ann Arbor.The rstwas an exhibition organizedas partof aninternationalsymposium on ‘ City,Space 1 Globalization’. The second wasa lecture by the renowned Dutch architectand urbanist, Rem Koolhaas. By themselves,the events generated much interestand discussion, yet were innocu- ous,compared to, say, Prince Charles’s controversialcomments on contempor- arycities in the UKorthe gathering momentumof the New Urbanism movementin the USA. -

244 Project 1 = 10% Sustainability 101 Design Manifesto

244 PROJECT 1 = 10% SUSTAINABILITY 101 DESIGN MANIFESTO WHAT • Write your vision for your career through a personal manifesto. Present it in the form of an 11X17” colour poster. Use concept, layout and typography to share your vision in a unique way. • Your target audience is future industry employers. Imagine that employerw will decide who to hire based on this poster. WHY • To document your understanding of sustainable design and to explore how you see it influencing your future practice. • To practice communicating a message quickly and engagingly in a poster format, using concept, layout, imagery, typography, etc. • To give you an opportunity to implement design principles such as balance, scale, colour, figure/ground and framing. HOW • Review the links to examples of past design manifestos for inspiration. • Consider what you’ve uncovered about sustainable design. What resonates with you? What elements of sustainable design will you apply in your work? • Design a poster that includes your name and demonstrates that you understand the four pillars of sustainability. Write your manifesto in one or several paragraphs. It’s a poster, so keep it to 150 words maximum. • Consider the vernacular and the sensibilities of your target audience. • Consider what kind of design will best reflect you and your personality as a designer. • Combine two different type families in your design, and use at least three levels of type hierarchy. • Consider how to inject your personal voice into the copy itself and the typography. • Sketch different ideas. Revise and refine. • Post a jpg/png of your poster on your blog along and provide a rationale. -

On the Value(S) of an Architect

2 A Discipline Adrift? Teaching Architectural Ethics in Today’s World On the Value(s) of an Architect ANASTASIA H. CORTES Virginia Tech This paper situates architectural ethics in the context of observer: they either like it or they don’t. Architects earn practice by using stakeholder theory and the concept of pro- professional degrees and are licensed, like doctors, lawyers, fessional judgment to describe the activities of architectural and engineers. However, architecture is the lowest paid of practice. Architects are taught the skills necessary to make these four professions. Although buildings are tangible arti- ethical professional judgments in the contexts of design and facts of an architect’s work, the design of a building is less professional service, but they are not necessarily taught easily understood by the lay person than, say, recovery from how to effectively communicate the value of those skills to an illness. Often the public may value the architect’s work those outside the profession. Stakeholder theory provides a based on the subjective evaluation of the observer: they framework to describe the practice of architecture in a way either like it or they don’t. The profession cannot survive on that enables non-practitioners to appreciate value of the the basis of the public’s “like” of their work, as discussed in complex decisions and activities performed by architects. a 2015 article in Forbes magazine, which declared contem- porary architecture to be ugly, irrelevant, and out of touch “There’s a snobbery at work in architecture…The sub- with society.3 In support of this claim, the author offered up ject is too often treated as a fine art, delicately wrapped a description of the American Institute of Architects’ effort in mumbo-jumbo. -

Building for the Future: Sustainable Home Design

Building for the Future Sustainable Home Design John Quale, Assistant Professor and ecoMOD Project Director University of Virginia School of Architecture U.S. Department of Energy environmental impact of buildings electricity usage carbon emissions source: www.architecture2030.org U.S. Department of Energy environmental impact of buildings • the U.S. generates and uses more energy than any other nation; more than half is used in the construction or operation of buildings • the U.S. is the world's largest generator of greenhouse gas emissions • the average single-family home in the U.S. emits more than 22,000 pounds of carbon dioxide each year (from the electricity generated by utilities to run the home, and oil or gas powered appliances and equipment in the home) this is more than twice the amount emitted by the typical American car • each day the sun directly radiates more than 10,000 times the amount of energy required in the world • less than 10 percent of single-family residences are designed by architects; of those, most are for the wealthy U.S. Department of Energy what is green design? design and construction practices that significantly reduce or eliminate the negative impact of buildings on the environment and occupants in five broad areas: . site . water . energy . materials . comfort U.S. Department of Energy how is it measured? energy and water use monitoring utility bills life cycle analysis / assessments post occupancy evaluations carbon neutrality assessments certification processes such as LEED or Energy Star or Earthcraft U.S. Department of Energy who is responsible? clients architects engineers landscape architects planners contractors policy makers government officials U.S. -

An Overview of the Building Delivery Process

An Overview of the Building Delivery CHAPTER Process 1 (How Buildings Come into Being) CHAPTER OUTLINE 1.1 PROJECT DELIVERY PHASES 1.11 CONSTRUCTION PHASE: CONTRACT ADMINISTRATION 1.2 PREDESIGN PHASE 1.12 POSTCONSTRUCTION PHASE: 1.3 DESIGN PHASE PROJECT CLOSEOUT 1.4 THREE SEQUENTIAL STAGES IN DESIGN PHASE 1.13 PROJECT DELIVERY METHOD: DESIGN- BID-BUILD METHOD 1.5 CSI MASTERFORMAT AND SPECIFICATIONS 1.14 PROJECT DELIVERY METHOD: 1.6 THE CONSTRUCTION TEAM DESIGN-NEGOTIATE-BUILD METHOD 1.7 PRECONSTRUCTION PHASE: THE BIDDING 1.15 PROJECT DELIVERY METHOD: CONSTRUCTION DOCUMENTS MANAGEMENT-RELATED METHODS 1.8 PRECONSTRUCTION PHASE: THE SURETY BONDS 1.16 PROJECT DELIVERY METHOD: DESIGN-BUILD METHOD 1.9 PRECONSTRUCTION PHASE: SELECTING THE GENERAL CONTRACTOR AND PROJECT 1.17 INTEGRATED PROJECT DELIVERY METHOD DELIVERY 1.18 FAST-TRACK PROJECT SCHEDULING 1.10 CONSTRUCTION PHASE: SUBMITTALS AND CONSTRUCTION PROGRESS DOCUMENTATION Building construction is a complex, significant, and rewarding process. It begins with an idea and culminates in a structure that may serve its occupants for several decades, even centuries. Like the manufacturing of products, building construction requires an ordered and planned assembly of materials. It is, however, far more complicated than product manufacturing. Buildings are assembled outdoors by a large number of diverse constructors and artisans on all types of sites and are subject to all kinds of weather conditions. Additionally, even a modest-sized building must satisfy many performance criteria and legal constraints, requires an immense variety of materials, and involves a large network of design and production firms. Building construction is further complicated by the fact that no two buildings are identical; each one must be custom built to serve a unique function and respond to its specific context and the preferences of its owner, user, and occupant. -

Regenerative Architecture: a Pathway Beyond Sustainability Jacob A

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2009 Regenerative Architecture: A Pathway Beyond Sustainability Jacob A. Littman University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Environmental Design Commons, and the Other Architecture Commons Littman, Jacob A., "Regenerative Architecture: A Pathway Beyond Sustainability" (2009). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 303. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/303 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REGENERATIVE ARCHITECTURE: A PATHWAY BEYOND SUSTAINABILITY A Thesis Presented by Jacob Alexander Littman Submitted to the Department of Art, Architecture and Art History of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE May 2009 Architecture + Design Program Department of Art, Architecture and Art History REGENERATIVE ARCHITECTURE: A PATHWAY BEYOND SUSTAINABILITY A Thesis Presented by Jacob Alexander Littman Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________ Skender Luarasi, Chairperson ____________________________ Ray K. Mann, Member ____________________________ Thom Long, Member ____________________________________ William Oedel, Department Head Department of Art, Architecture and Art History ABSTRACT REGENERATIVE ARCHITECTURE: A PATHWAY BEYOND SUSTAINABILITY MAY, 2009 JACOB LITTMAN, B.A., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST M.A., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Directed by: Professor Skender Luarasi The current paradigm in the field of architecture today is one of degeneration and obsolete building technologies. Regenerative architecture is the practice of engaging the natural world as the medium for, and generator of the architecture. -

Architecture

Architecture Architects are licensed professionals who design buildings and other structures. The design of a building involves far more than its appearance alone. Buildings also must be functional, safe, economical, and suit the needs of the people who use them. There are three main steps to become an architect: the attainment of a professional degree in architecture, work experience through an internship, and licensure through the passing of the Architect Registration Exam. Explore Become an Architect at NCARB.org. Degree Students choose from three paths to obtain a professional degree in architecture: • 5-year Bachelor of Architecture (B. Arch) degree: most transfer students do not choose this option due to course sequencing or • 2-year master’s degree after obtaining a 4-year bachelor’s degree in architecture or related area (M. Arch) or • 3 to 4-year master’s degree after obtaining a 4-year bachelor’s degree in a major other than architecture (M. Arch) Criteria of Importance for Acceptance to Architecture School May Include • Grade point average • Portfolio if required (freehand drawing, painting, graphic design, sculpture, etc.) • Personal interview • Past practical work experience related to the field (construction, building, planning, etc.) • Strong art, math, and science skills (especially physics) Important Notes • Due to the sequential nature of the coursework, transfer applicants for bachelor degree programs in architecture are often considered for admission as first year students. Four or five additional years to complete the program may be required. • Each architecture school has its own set of requirements. Research each school for specific information. • Make sure to check application deadline dates. -

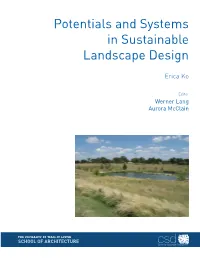

Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design

Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design Erica Ko Editor Werner Lang Aurora McClain csd Center for Sustainable Development II-Strategies Site 2 2.2 Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design Erica Ko Based on a presentation by Ilse Frank Figure 1: Five-acre retention pond and native prairie grasses filter and slowly release storm water run-off from adjacent residential development at Mueller Austin, serving an ecological function as well as an aesthetic amenity. Sustainable Landscape Design quickly as possible using heavy urban infra- structure. Today, we are more likely to take Landscape architecture will play an important advantage of the potential for reusing water role in structuring the cities of tomorrow by onsite for irrigation and gray water systems, for allowing landscape strategies to speak more providing habitat, and for slowing storm water closely to shifting cultural paradigms. A de- flows and allowing infiltration to groundwater signed landscape has the ability to illuminate systems—all of which can inspire new forms the interactions between a culture’s view of for integrating water into the built environ- its societal structure and its natural systems. ment. Water can be utilized in remarkable Landscape architecture employs many of the variety of ways–-as a physical boundary, an same design techniques as architecture, but is ecological habitat, or even a waste filtration unique in how it deals with time as a function system. A large-scale example of an outmoded of design (Figure 2), its materials palette, and approach is the Rio Bravo/Rio Grande, which how form is made.