Historical Resource Evaluation of Bancroft Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phase I Environmental Site Assessment Location Westfield Valley Fair Expansion Stevens Creek Boulevard Santa Clara and San Jose, California

Type of Services Phase I Environmental Site Assessment Location Westfield Valley Fair Expansion Stevens Creek Boulevard Santa Clara and San Jose, California Client David J. Powers & Associates Client Address 1871 The Alameda, Suite 200 San Jose, California 95126 Project Number 118-39-1 Date January 21, 2013 Prepared by Stason I. Foster, P.E. Senior Project Engineer Ron L. Helm, C.E.G., C.Hg. Senior Principal Geologist Table of Contents SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 1 1.1 PURPOSE ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 SCOPE OF WORK ................................................................................................ 2 1.3 ASSUMPTIONS .................................................................................................... 2 1.4 ENVIRONMENTAL PROFESSIONAL .................................................................. 2 SECTION 2: SITE DESCRIPTION .................................................................................. 2 2.1 SITE LOCATION, CURRENT USES AND OWNERSHIP ...................................... 3 2.3 SITE SETTING AND ADJOINING SITE USE ........................................................ 4 SECTION 3: USER PROVIDED INFORMATION ............................................................ 4 3.1 CHAIN OF TITLE .................................................................................................. 4 3.2 ENVIRONMENTAL LIENS OR -

UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer

UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer Photographs - Job Number Index Description Job Number Date Thompson Lawn 1350 1946 August Peter Thatcher 1467 undated Villa Moderne, Taylor and Vial - Carmel 1645-1951 1948 Telephone Building 1843 1949 Abrego House 1866 undated Abrasive Tools - Bob Gilmore 2014, 2015 1950 Inn at Del Monte, J.C. Warnecke. Mark Thomas 2579 1955 Adachi Florists 2834 1957 Becks - interiors 2874 1961 Nicholas Ten Broek 2878 1961 Portraits 1573 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1517 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1573 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1581 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1873 circa 1945-1960 Portraits unnumbered circa 1945-1960 [Naval Radio Training School, Monterey] unnumbered circa 1945-1950 [Men in Hardhats - Sign reads, "Hitler Asked for It! Free Labor is Building the Reply"] unnumbered circa 1945-1950 CZ [Crown Zellerbach] Building - Sonoma 81510 1959 May C.Z. - SOM 81552 1959 September C.Z. - SOM 81561 1959 September Crown Zellerbach Bldg. 81680 1960 California and Chicago: landscapes and urban scenes unnumbered circa 1945-1960 Spain 85343 1957-1958 Fleurville, France 85344 1957 Berardi fountain & water clock, Rome 85347 1980 Conciliazione fountain, Rome 84154 1980 Ferraioli fountain, Rome 84158 1980 La Galea fountain, in Vatican, Rome 84160 1980 Leone de Vaticano fountain (RR station), Rome 84163 1980 Mascherone in Vaticano fountain, Rome 84167 1980 Pantheon fountain, Rome 84179 1980 1 UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer Photographs - Job Number Index Quatre Fountain, Rome 84186 1980 Torlonai -

SABADO, VENTURA NONEZA, 83, of Honolulu, Died Feb. 8, 1993. He

SABADO, VENTURA NONEZA, 83, of Honolulu, died Feb. 8, 1993. He was born in Luna, La Union, Philippines, and was formerly employed as a tailor at Andrade’s and Ross Sutherland. Survived by wife, Lourdes S.; daughters, Mrs. Domi (Rose) Timbresa and Mrs. Robert (Carmen) McDonald; six grandchildren; sister, Teresa of the Philippines; nieces and nephews. Friends may call from 6 to 9 p.m. Friday at Borthwick Mortaury; service 7 p.m. Mass 9:45 a.m. at St. Patrick Catholic Church. Burial at Diamond Head Memorial Park. Aloha attire. [Honolulu Advertiser 16 February 1993] SABADO, VENTURA NONEZA, 83, of Honolulu, died Feb. 8, 1993. He was born in Luna, La Union, Philippines, and was formerly employed as a tailor at Andrade’s and Ross Sutherland. Friends may call from 6 to 9 p.m. Friday at Borthwick Mortuary; service 7 p.m. Mass 9:45 a.m. Saturday at St. Patrick Catholic Church. Burial at Diamond Head Memorial Park. Aloha attire. A recent obituary was incomplete. [Honolulu Advertiser 17 February 1993] Saballus, Doriel L., of Honolulu died last Thursday in St. Francis Hospital. Saballus, 46, was born in Berkeley, Calif. She is survived by husband Klaus; daughter Stephanie; parents Leo and Charlene Dwyer; and sister Leslie Dwyer. Services: 3 p.m. Saturday at Borthwick Mortuary. Calla after 2:30 p.m. Casual attire. No flowers. Memorial donations suggested to St. Francis Hospice. [Honolulu Star-Bulletin 7 January 1993] SABALLUS, DORIEL LEA, 46, of Honolulu, died Dec. 31, 1992. She was born in Berkeley, Calif. Survived by husband, Klaus; daughter, Stephanie; parents, Leo and Charlene Dwyer; sister, Leslie Dwyer; a nephew; au aunt. -

OVS-Alumni-Notes-Spring-2018-Proof.Pdf

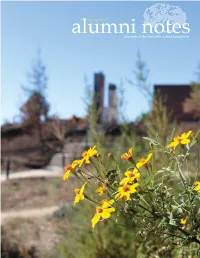

spring 2018 a branch of the ojai valley school family tree BOARD OF TRUSTEES Mr. John B. De Nault III Chairman Mr. Michael J. Hall-Mounsey President/CEO Mrs. Patricia H. Farber Treasurer Mr. Lawrence Fisher Secretary Dr. Robert G. Cooper Jr. (L61) Mr. Spencer Garrett (L62, U65) Mr. William H. Hair Mr. Andrew Helman Ms. Gail “Gigi” Ordway (U78) Mrs. Missy Stoen Mr. Nicholas Thacher (L60) Mr. David Trudeau CHAIRMAN EMERITUS: Mr. A. Carl Kotchian, 1914-2008 PRESIDENTS EMERITI: Mr. Edward Yeomans 1865-1942 Mr. Michael D. Hermes (L53) 1938-2011 HEADMASTER EMERITUS: Mr. Wallace Burr, 1904-1996 MEMBERS EMERITI: Mr. Robert E. Chesley, 1932-2003 Mr. David J. Donlon, 1930-2009 Mr. Benjamin E. Nordman, 1913-1985 Mr. Anson S. Thacher, 1905-1994 CONTRIBUTORS: Thank you to the writers, editors, and photographers who contributed to this edition of Alumni Notes, including Joy Campbell (L14, U18), Avery Colborn (L16, U20), Emma Gustafson (L14, U18), Caroline Morrow (L15, U19), Lilli Trompke (U19), Fred Alvarez, Misty Hall, Craig Floyd, Malory Taylor, John Wickenhaeuser, and Tracy Wilson. ALUMNI ON THE COVER: WEEKEND Native plants emerge outside the Grace Hobson Smith girls JUNE 8-10 dormitory at the Upper Campus. The dorm was destroyed during the Thomas Fire. Photo by Misty Hall Alumni Weekend Registration is now open! Sign up online at www.ovs.org/aw See page 20 for more information about this year’s program. 2 PRESIDENT'S PAGE Little did we know that the distant plume of smoke to the east of the Upper Campus would have such a widespread impact on Ojai Valley School. -

Eton Profs Stripped of Personnel Rights Unplanned Bugs Creep Into CAR 1

1 Tuesday, September 10, 1974 Spartan Daily Serving San Jose State University Since 1934 Eton profs stripped of personnel rights 11, By Phil Trounstine Burns, was termed the destruction of teaching records, path breaking PhD the department." Tenured professors in the Economics academic freedom" by several tenured dissertations finished or in progress Willis said he did not think the action Departnient Friday were stripped of economics professors. and 100 per cent support from was a threat to academic freedom. the right to participate in departmental Those professors revealed their students?" asked O'Connor. "The department is part of the personnel matters. version of the events inside the He called the firings an "attack on university community, and the question The faculty, for an indefinited period department only with a promise of cirtical thought and democratic norms of collegial government really has to do of time, will have no voice in hiring, confidentiality. They said they feared in the Economics Department." with the university community. If some firing, recruitment, promotions, administrative reprisals if their names Policies questioned parts of it are defficient in their per- reviews or other personnel committee became known. Another point of contention, sources formance, then some other kind of functions within the department. Committee formed reported, was the process and decisions faculty consultation has to be The department will be governed by a to hire new faculty members and fire provided," Willis said. Spartan Daily reporters were or- six -person executive committee, others. Additional assesment dered to leave the meeting Friday headed by Economics Deartment Dr. Willis insisted the faculty should But various professors had another between Academic Vice President Chairman Dr. -

San Francisco Ephemera Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2p30342b No online items San Francisco Ephemera Collection Finding aid prepared by David Krah, Stephanie Walls, and California Ephemera Project staff; updated by San Francisco History Center staff. The California Ephemera Project was funded by a Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources in 2009-2010. San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA, 94102 415-557-4567 [email protected] 2010, updated Dec. 2012 San Francisco Ephemera SF SUB COLL 1 Collection Title: San Francisco ephemera collection Date (inclusive): 1850-2012 Collection Identifier: SF SUB COLL Extent: 265.0 Linear feet (153 file drawers) Contributing Institution: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA, 94102 415-557-4567 [email protected] Physical Location: Collection is stored onsite; some materials require retrieval from separate storage. Language of Materials: Collection materials are in English. Abstract: Consists of ephemeral materials, city records and clippings relating to the city of San Francisco and its citizens. Materials date from the 1850s to the present, the bulk from the 20th century. Subjects cover a diverse array of San Francisco history and primarily pertain to: municipal government; city planning; urban policy; environmental engineering; transportation; social history; labor history; community relations; notable events; public events, fairs and celebrations; and various aspects of local popular culture. Subjects also relate to specific local entities, such as: businesses; schools, colleges and universities; political parties; and associations, groups and clubs. Specific places are also found here, including: buildings; public spaces; bodies of water; and transportation terminals. -

City Council Staff Report

CITY COUNCIL STAFF REPORT DATE: January 16, 2013 PUBLIC HEARING SUBJECT: CASE HSPB #84: APPLICATION FOR DESIGNATION OF THE (J.w. ROBINSONS DEPARTMENT STORE / ROBINSONS SPECIALTY SHOPS / "THE ALLEY" LOCATED AT 333 - 343 SOUTH PALM CANYON DRIVE AS A CLASS 1 HISTORIC SITE FROM: David H. Ready, City Manager BY: The Planning Department SUMMARY Under Section 8.05 of the Palm Springs Municipal Code (Historic Resources), the City Council may designate properties as "Class 1" historic sites. The City's Historic Site Preservation Board (HSPB) has recommended such a designation for the entire site, at 333 - 343 South Palm Canyon Drive ("J.W. Robinsons Department Store / Robinsons Specialty Shops / The Alley"). The property owner has expressed opposition to the designation. The Council will conduct a public hearing and determine if the site should be designated. Class 1 designation wou'ld place the building under the guidance of Municipal Code Section 8.05 "Historic Preservation". RECOMMENDATION 1. Open the public hearing and accept public testimony. 2. Adopt Resolution No. : "A RESOLUTION OF THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF PALM SPRINGS, CALIFORNIA DESIGNATING THE PROPERTY LOCATED AT 333 - 343 S. PALM CANYON DRIVE C'J.W. ROBINSONS BUILDING / THE ALLEY") AS A HISTORIC SITE, CLASS 1 - HSPB 84" PROJECT DESCRIPTION The HSPB initiated an investigation to determine if the subject property should be . designated a Class 1 historic site. Such designation would: 1. Place the subject property under the guidance of Municipal Code Section 8.05 ITEM NO. \Pv City Council Staff Report January 16, 2013 Case: HSPB No. 84; 333 - 343 S. -

September 30, 2014 HISTORIC RESOURCES GROUP 12 S

City of Glendale South Glendale Historic Context Statement September 30, 2014 HISTORIC RESOURCES GROUP 12 S. Fair Oaks Avenue, Suite 200, Pasadena, CA 91105-1915 Telephone 626-793-2400, Facsimile 626-793-2401 www.historicla.com South Glendale Community Plan • City of Glendale, CA Appendix A.1 DRAFT 9 Jan 2018 PREPARED FOR City of Glendale Planning Division 633 E. Broadway Glendale, CA 91206 Attn: Jay Platt, Senior Urban Designer City of Glendale South Glendale Historic Context HISTORIC RESOURCES GROUP South Glendale Community Plan • City of Glendale, CA Appendix A.1 DRAFT 9 Jan 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Project Summary 4 Project Introduction 5 Guidelines for Evaluation 9 Historic Context 18 Context: Early History & Development (Pre-1771-1881) 24 Theme: Native Americans: The Gabrielinos (Pre-1771) 24 Theme: Spanish Colonization and The Mission San Gabriel Arcangel (1771-1822) 25 Theme: Rancho San Fafael and the Great Partition (1822-1871) 25 Property Types & Registration Requirements 26 Context: Early Development & Town Settlement (1872-1918) 28 Property Types & Registration Requirements 57 Context: Single-Family Residential Development (1919-1979) 61 Theme: Pre-World War II Automobile Suburbs (1919-1944) 61 Sub-theme: 1920s Hillside Development 69 Property Types & Registration Requirements 74 Theme: Post-World War II Single-Family Residential Development (1945-1979) 79 Property Types & Registration Requirements 85 Context: Multi-Family Residential Development (1910-2000) 89 Theme: Pre-World War II Multi-Family Residential Development (1910-1944) -

Macdonald Becket Papers Documenting the Work of Wurdeman and Becket, Welton Becket and Associates, and the Becket Group

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c82b93f2 No online items Finding aid for the MacDonald Becket papers documenting the work of Wurdeman and Becket, Welton Becket and Associates and the Becket Group, 1944-2011 Ann Harrison 2012.M.43 1 Descriptive Summary Title: MacDonald Becket papers documenting the work of Wurdeman and Becket, Welton Becket and Associates, and the Becket Group Date (inclusive): 1944-2011 Number: 2012.M.43 Creator/Collector: Becket, MacDonald Physical Description: 56 Linear Feet(41 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Albums of clippings, letters, photographs and ephemera, as well as brochures, company newsletters and related materials collected by MacDonald Becket, document the work of the successive architectural firms of Wurdeman and Becket, Welton Becket and Associates, and the Becket Group. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English. Biographical/Historical Note Born and raised in Seattle, Washington, MacDonald Becket received his B.Arch in 1952 from the University of Southern California (USC). While still a student, Becket began to work part-time at Wurdeman and Becket, the Los Angeles architecture firm of his uncle, Welton Becket. From the summer of 1948, which he spent operating a blueprint machine, MacDonald Becket progressed through the ranks of the firm. Upon his graduation from USC, he became a project manager for Welton Becket and Associates, the new firm his uncle formed after the death of Walter Wurdeman. -

Victor Gruen, Visionary Pioneer of Urban Revitalization

TEE ARCHrrECT AS CREATOR OF ENWRONMENTS: VICTOR GRUEN, VISIONARY PIONEER OF URBAN REVrrALIZATIONS by DAVID J. AZRTELI, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulnllment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture School of Architecture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ApnI 1997 PART 1 National Library Bibliothèque nationale I*!of Canada du Canada Acquisiîions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Ywrfik Vmnifémca Our nk, None rélihenar The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, disûiiute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/f3m, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format élecironique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Carleton University Ottawa, Canada K 1S 5J7 Thesis contains black and white and/or coloured graphs/tables/photographs which when microf ilmed may lose their signf- f icance. The hardcopy of the thesis is available upon request from Carleton University ~ibrary. -

Feasibility of Proposed Universal City Specialty Center

University of Central Florida STARS Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers Digital Collections 9-19-1966 Feasibility of Proposed Universal City Specialty Center Economics Research Associates Part of the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/buzzprice University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collections at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Economics Research Associates, "Feasibility of Proposed Universal City Specialty Center" (1966). Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers. 150. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/buzzprice/150 _., :l . ( FEASIBILITY OF PROPOSED UNIVERSAL CITY SPECIALTY CENTER Prepared for MCA INC. September 19, 1966 ECONOMICS RESEARCH ASSOCIATES LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA TABLE OF CONTENTS Section INTRODUCTION .. ...... 1 I SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS. 1-1 II ANALYSIS OF UNIVERSAL CITY SITE AND ITS ENVIRONMENT Il-l Location Il-l Access . Il-l Immediate Environment II- 3 Existing and Planned Developments on the Site. II- 3 III SELECTING A SITE FOR THE RETAIL CENTER ... .. .. 111-1 Possible Sites ...... 111-1 Can the Site Accommodate a Department Store? ..... .. III- 3 A Retail Center Without a Department Store. 111-3 IV OTHER RETAIL CENTERS AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE FOR UNIVERSAL CITY .. IV -1 Foreign Shopping Districts. IV -1 Shopping Districts in the United States. IV-2 Other Retail Centers and Their Significance for Universal City . , . .. .. IV -11 What Makes a Successful Center? . IV -11 Applying the Lessons of Other Centers to Universal City ..... -

Athletics 'Not Priority'

Thursday, March 8, 1973 Beall questions Spartan environs study Serving California State University at San Dail*Jose Since 1 934 By BILL PATERSON a lack ot replacement facilities olunteer San lose Planning Com- should Spartan City be displaced. mission member lames Beall is dis- He also contends if Spartan City satisfied with the city's en- remains, the stadium expansion may vironmental impact study on the mean increased levels of congestion, Districting controversy brewing; proposed Spartan Stadium expan- noise and air pollution that would sion. adversely affect residents. "I think there are some unanswered "If so. the project would lead to a questions on what effect the stadium public controversy. involving the expansion will have on Spartan students at California State Cit y." he said. "The study hasn't dune University, San lose." he wrote. councilmen Co//a, Garza, comment this." Bill Allison, manager of the SISU Spartan City, constructed as tem- Auxiliary Enterprises which By GAIL skikomoTo representation ol Chicanos in city inflexible, as to not sit down and demaroting more accountability from porary housing during World War II, operates Spartan City. said, "We First of three parts government." rationally consider districting?" their council members. As a result, is a small, inexpensive housing com- don't have any plans to move." "I'm opposed to districting, and I According to Collo, however, es- asked Garza. "That's what is when people realize that through dis- munity in the south campus area for Allison, who has not read the im- think the voters of this community tablishing a Chicano district will not happening right now.