Kufa Vs Basra : the Literary Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of 5 Qafela of Ahle Bayt Journey from Karbala to Kufa to Shaam and Then

SIJILL A WEEKLY NEWSLETTER OF FATEMIDAWAT.COM Issue 94 Qafela of Ahle Bayt journey from Karbala to Kufa to Shaam and then Featured updates: Medina after Aashura SIJILL ARTICLE: Ten Virtues of a بسم الل ه الرحمن الرحيم Mumin – (5) Sincere Repentence Having been blessed with the greatest virtue, the valaayat of Amirul يَا َأ يُه َا ال َذِي َن آمَن ُوا ت ُوب ُوا ِإل َى الل َهِ ت َوْب َةً ن َ ُصوحًا Mumineen SA, it is incumbent on us to (Surat al-Tahrim: 8) be worthy of such a great blessing that MARSIYA: Ay Karbala tu hi suna O ye who believe! Turn to Allah with sincere ensures our salvation. Rasulullah SA has said that “he who is given the gift repentance. (rizq, rozi) of thevalaayat of Ali has attained the goodness of this world بسم الل ه الرحمن الرحيم and the Hereafter, and I do not doubt that he will enter jannat. In Ali’s love مَ ْن رَزَق َه ُ الل ه ُ وَلاي َةَ ع َل ِي اب ِن ابيطالب صع ف َقَ ْد َأ َصا َب and valaayat are twenty virtues: 10 in خَيْرَ الدُنْيَا والآخِرةِ، ولا أشُكُ لهُ بِالجَنةِ، وإنَ في حُبِ this world (dunya) and 10 in the ع َلي وَوَلايَتِهِ عِشْرِينَ خَصْ لَة، عَشَرةً مِنها في الدُنيا وعَشَرةً Hereafter (aakherat).” The first of the virtues in this world is zuhd (renouncing في الآخرة* )1( الزهد )2( والحرص على العلم )3( materialism – lit. asceticism – see Sijill والورع في الدين )4( والرغبة في العبادة )5( وتوبة Article 90). The second of the virtues in نصوح this world is desire (lit. -

Basrah Governorate Profile

Basrah Governorate Profile Source map: JAPU Basrah at a Glance Fast Facts Area: 19,070 km2 Capital City: Basrah Average High Temperatures: 17,7°C Average Low Temperatures: 6,8°C (January) to 41,8°C (August) (January) to 27,4°C (July) Population: 2,403,301 Population Distribution Rural-Urban: 20,1%-79,9% Updated December 2015 Geography and Climate Basrah is the most southern governorate of Iraq and borders Iran, Kuwait and Saudi-Arabia. In the south, the governorate is made up of a vast desert plain, intersected by the Shatt Al-Arab waterway which is formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers at Al-Qurnah and empties into the Persian Gulf. Around Al-Qurnah and Al-Medina a number of lakes can be found, while marshland stretches from the north of the governorate into the neighboring governorates of Thi-Qar and Missan. The governorate is Iraq’s only access to the sea. Similar to the surrounding region, the governorate of Basrah has a hot and arid climate. The temperatures in summer are among the highest recorded in the world. Due to the vicinity of the Persian Gulf, humidity and rainfall are however relatively high. The governorate receives an average amount of 152mm of rainfall a year between the months of October and May. Population and Administrative Division The governorate of Basrah is subdivided into seven districts: Abu Al-Khaseeb, Al-Midaina, Al-Qurna, Al- Zubair, Basrah, Fao, and Shatt Al-Arab. The city of Basrah, the governorate’s capital, is Iraq’s third largest urban center. -

![2021 VNR Report [English]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7615/2021-vnr-report-english-227615.webp)

2021 VNR Report [English]

The Republic of Iraq Ministry of Planning National Committee for Sustainable Development The Second National Voluntary Review Report on the Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals 2021 Iraq .. And the Path Back to the Development July 2021 Voluntary National Review Report Writing Team Dr. Mahar Hammad Johan, Deputy Minister of Planning, Head of the Report Preparation Team Writing Expert Team Prof. Dr. Hasan Latif Al-Zubaidi / Expert / University of Kufa / College of Administration and Economics Prof. Dr. Wafa Jaafar Al-Mihdawi / Expert / Mustansiriyah University / College of Administration and Economics Prof. Dr. Adnan Yasin Mustafa / Expert / University of Baghdad / College of Education for Girls Supporting International organizations United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) – Iraq United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) Technical Team Dr. Azhar Hussein Saleh / Administrative Deputy of Minister of Planning Dr. Dia Awwad Kazem / Head of the Central Statistics Organization Mr. Maher Abdul-Hussein Hadi / Director General of the National Center for Administrative Development and Information Technology Dr. Mohamed Mohsen El-Sayed / Director General of the Department of Regional and Local Development Dr. Alaa El-Din Jaafar Mohamed / Director General of the Department of Financial and Economic Policies Dr. Maha Abdul Karim Hammoud / Director General of the Department of Human Development Ms. Naglaa Ali Murad / Director of the Social Fund for Development Mr. Abdel-Zahra Mohamed Waheed / Director of the Department of Information and Government Communications Dr. Amera Muhammad Hussain / Umm Al-Yateem Foundation for Development Mrs. Ban Ali Abboud / Expert / Department of Regional and Local Development Ms. Mona Adel Mahdi / Senior Engineer / Department of Regional and Local Development Supporting Team Mr. -

A Tale of Two Cities the Use of Explosive Weapons in Basra and Fallujah, Iraq, 2003-4 Report by Jenna Corderoy and Robert Perkins

December 2014 A TALE OF TWO CITIES The use of explosive weapons in Basra and Fallujah, Iraq, 2003-4 Report by Jenna Corderoy and Robert Perkins Editor Iain Overton With thanks to Henry Dodd, Jane Hunter, Steve Smith and Iraq Body Count Copyright © Action on Armed Violence (December 2014) Cover Illustration A US Marine Corps M1A1 Abrams tank fires its main gun into a building in Fallujah during Operation Al Fajr/Phantom Fury, 10 December 2004, Lance Corporal James J. Vooris (UMSC) Infographic Sarah Leo Design and Printing Matt Bellamy Clarifications or corrections from interested parties are welcome Research and publications funded by the Government of Norway, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A tale of two cities | 1 CONTENTS FOREWORD 2 IRAQ: A TIMELINE 3 INTRODUCTION: IRAQ AND EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS 4 INTERnatiONAL HumanitaRIAN LAW 6 AND RulES OF ENGAGEMENT BASRA, 2003 8 Rattling the Cage 8 Air strikes: Munition selection 11 FALLUJAH, 2004 14 Firepower for manpower 14 Counting the cost 17 THE AFTERmath AND LESSONS LEARNED 20 CONCLUSION 22 RECOMMENDatiONS 23 2 | Action on Armed Violence FOREWORD Sound military tactics employed in the pursuit of strategic objectives tend to restrict the use of explosive force in populated areas “ [... There are] ample examples from other international military operations that indicate that the excessive use of explosive force in populated areas can undermine both tactical and strategic objectives.” Bård Glad Pedersen, State Secretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway, 17 June 20141 The language of conflict has changed enormously. their government is not the governing authority. Today engagements are often fought and justified Three case studies in three places most heavily- through a public mandate to protect civilians. -

Call for Proposal

CALL FOR PROPOSAL Ref. No.: CFP/IRQ/2019-005 < Construction of a Potable Water Network and organization of a Garbage Collection Campaign in the informal settlement Al-Qibla in Basra City, Basra Governorate > Purpose of CFP: Improving living conditions in the targeted informal settlement through infrastructure upgrading and solid waste collection, with an emphasis on providing on-the-job training and local employment, in addition to the mobilization of community members to conduct environmental initiatives through cash for work. Submission Start Date: 24 Apr 2019 Submission Deadline Date and time: 08 May 2019, at 3 pm Key Project Information UN-Habitat Project title: Construction of a Potable Water Network and organization of a Garbage collection campaign in the informal settlement of Al-Qibla in Basra City, Basra Governorate Locations: Town/City: Al Qibla in Basra City, Basra Governorate Country: Iraq Anticipated start date: 26 May 2019 Estimated duration of project in calendar months: 33 days Maximum proposed value in US$: US$ 180,000 Lead Organizations Unit : UN-Habitat-Iraq Page 1 of 7 A. Brief Background of the Project In late 2014, UN-Habitat launched a comprehensive ‘National Informal Settlements Program’ comprising of institutional, legal, financial and technical pillars to carry out thorough diagnostic of the existing urban informal areas, and to identify appropriate technical planning solutions for their regularization and upgrading. Efforts focused on conducting an intensive review of the available financial mechanisms and the development of a Roadmap (endorsed by the Cabinet’s resolution No. 279 of 2015) that provides the strategic directions of the national programme and securing policy support within the Government of Iraq (GoI) through an appropriate institutional setup, followed by mapping and analysis of informal settlements in Iraq. -

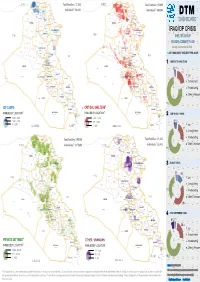

IDP and Refugee Camp Locations - As of January 2017

For Humanitarian Purposes Only IRAQ Production date: 01 February 2017 IDP and Refugee Camp Locations - As of January 2017 Za k ho T U R K E Y Darkar ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑⛳⚑Bersive II Chamishku Bersive I Dawudiya ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Am e di Bajet Kandala ² Rwanga Dahuk Community Me r ga s ur Da h uk Su m el So r an !PDahuk Kabrato I+II Ak r e Khanke ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Shariya S Y R I A ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Sh i kh a n Domiz I+II Essian Akre ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Sheikhan Amalla ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Garmawa ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑Mamrashan ⛳⚑ Mamilian ⛳⚑Nargizlia Ch o ma n 1 + 2 Tel af ar Ti lk a if Qaymawa ⛳⚑ Basirma ⛳⚑ Bardarash Darashakran ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Sh a ql a w a Si n ja r Hasansham M2 Gawilan Kawergosk Mosul!P ⛳⚑ I R A N Hasansham U3 ⛳⚑⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Baharka ⛳⚑ Ps h da r Ha m da n iy a Khazer M1 Ra n ia Harsham ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Erbil Ankawa 2 !P Erbil Mo s ul Ninewa Er b il Ko i sn j aq Qushtapa ⛳⚑ Do k an Debaga 1 ⛳⚑ Debaga 4 ⛳⚑⛳⚑ Surdesh Debaga Debaga 2 ⛳⚑ Stadium Ba 'a j Hasiyah ⛳⚑ Tina ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Qayyarah-Jad'ah Sh a rb a zh e r Pe n jw i n Ma k hm u r Ki r ku k Da b es Sulaymaniyah !P Barzinja Kirkuk ⛳⚑ Su l ay m an i y ah Ha t ra !P Arbat IDP ⛳⚑ Sh i rq a t ⛳⚑ Ashti IDP Nazrawa ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑Arbat Refugee Yahyawa ⛳⚑⛳⚑ Laylan 1 Sulaymaniyah Ha w ig a Kirkuk Da r ba n d ih k an Daquq ⛳⚑ Ch a mc h a ma l Laylan 2 ⛳⚑ Ha l ab j a Da q uq Ka l ar Hajjaj Camp ⛳⚑ Al-Alam ⛳⚑⛳⚑2 (MoMD) Ba i ji Al Alam 1 To oz (UNHCR) Tik r it Tazade ⛳⚑Al Safyh ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Tikrit Ru 'u a University Qoratu ⛳⚑ Al Obaidi Ki f ri ⛳⚑ Salah al-Din Da u r Ka 'i m Al Wand 1 Al Wand 2⛳⚑ Ha d it h a Sa m ar r a Al Abassia Al-Hawesh ⛳⚑ Kh a na q in ⛳⚑ !P Samarra Al-Iraq Al-Hardania Al-Muahad ⛳⚑ Diyala ⛳⚑ -

Weekly Explosive Incidents Flas

iMMAP - Humanitarian Access Response Weekly Explosive Hazard Incidents Flash News (25 June - 01 July2020) 79 673 11 6 4 INCIDENTS PEOPLE KILLED PEOPLE INJURED EXPLOSIONS AIRSTRIKES Federal Police Forces 01/JUL/2020 DIYALA GOVERNORATE Found and cleared 22 IEDs in Samarra district. Security Forces 25/JUN/2020 SALAH AL-DIN GOVERNORATE Destroyed an ISIS hideout and cleared a cache of explosives containing seven mortar Security Forces 25/JUN/2020 shells, three homemade IEDs, three detonators, and ammunition. Found and cleared a cache of explosives belonging to ISIS in the Al-Dhuluiya subdistrict. An Armed Group 26/JUN/2020 Coalition Forces 26/JUN/2020 Shot and killed a Security Forces member near Abu Al-Khanazer village on the outskirts of Launched several airstrikes and destroyed many ISIS hideouts and tunnels, killing 24 Abi Said subdistrict, northeast of Baqubah district. insurgents in Khanuka mountain. Popular Mobilization Forces 26/JUN/2020 Military Intelligence 29/JUN/2020 Destroyed five ISIS hideouts and killed five insurgents in the Al-Adhim area, north of Diyala. Found and cleared 24 IEDs and artillery shells in the Mukayshafa desert of Samarra district. ISIS 27/JUN/2020 Killed four Federal Police Forces members and injured two others in an attack at Abu Coalition Forces 29/JUN/2020 Al-Khanazer village, northeast of Baqubah district. Launched several airstrikes and destroyed many ISIS hideouts, killing everyone inside in Makhoul mountain of Baiji district. Popular Mobilization Forces 27/JUN/2020 Repelled an ISIS attack in Sheikh Jawamir village, north of Muqdadiya district. An Armed Group 30/JUN/2020 A targeted IED explosion struck a Popular Mobilization Forces patrol, killing four members Popular Mobilization Forces 27/JUN/2020 and injuring another, west of Baiji district. -

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE and HERITAGE Basra Its History, Culture and Heritage

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE CULTURE : ITS HISTORY, BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins Edited by Paul Collins BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins © BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ 2019 ISBN 978-0-903472-36-4 Typeset and printed in the United Kingdom by Henry Ling Limited, at the Dorset Press, Dorchester, DT1 1HD CONTENTS Figures...................................................................................................................................v Contributors ........................................................................................................................vii Introduction ELEANOR ROBSON .......................................................................................................1 The Mesopotamian Marshlands (Al-Ahwār) in the Past and Today FRANCO D’AGOSTINO AND LICIA ROMANO ...................................................................7 From Basra to Cambridge and Back NAWRAST SABAH AND KELCY DAVENPORT ..................................................................13 A Reserve of Freedom: Remarks on the Time Visualisation for the Historical Maps ALEXEI JANKOWSKI ...................................................................................................19 The Pallakottas Canal, the Sealand, and Alexander STEPHANIE -

20141214 04 IOM DTM Repor

TURKEY Zakho Amedi Total Families: 27,209 TURKEY Zakho Amedi TURKEY Total Families: 113,999 DAHUK Mergasur DAHUK Mergasur Dahuk Sumel 1 Sumel Dahuk 1 Soran Individual : 163,254 Soran Individuals : 683,994 DTM Al-Shikhan Akre Al-Shikhan Akre Tel afar Choman Telafar Choman Tilkaif Tilkaif Shaqlawa Shaqlawa Al-Hamdaniya Rania Al-Hamdaniya Rania Sinjar Pshdar Sinjar Pshdar ERBIL ERBIL DASHBOARD Erbil Erbil Mosul Koisnjaq Mosul Koisnjaq NINEWA Dokan NINEWA Dokan Makhmur Sharbazher Penjwin Makhmur Sharbazher Penjwin Dabes Dabes IRAQ IDP CRISIS Al-Ba'aj SULAYMANIYAH Al-Ba'aj SULAYMANIYAH Hatra Al-Shirqat Kirkuk Hatra Al-Shirqat Kirkuk Sulaymaniya Sulaymaniya KIRKUK KIRKUK Al-Hawiga Chamchamal Al-Hawiga Chamchamal DarbandihkanHalabja SYRIA Darbandihkan SYRIA Daquq Daquq Halabja SHELTER GROUP Kalar Kalar Baiji Baiji Tooz Tooz BY DISPLACEMENT FLOW Ra'ua Tikrit SYRIA Ra'ua Tikrit Kifri Kifri January to December 9, 2014 SALAH AL-DIN Haditha Haditha SALAH AL-DIN Samarra Al-Daur Khanaqin Samarra Al-Daur Khanaqin Al-Ka'im Al-Ka'im Al-Thethar Al-Khalis Al-Thethar Al-Khalis % OF FAMILIES BY SHELTER TYPE AS OF: DIYALA DIYALA Ana Balad Ana Balad IRAN Al-Muqdadiya IRAN Al-Muqdadiya IRAN Heet Al-Fares Heet Al-Fares Tar m ia Tarm ia Ba'quba Ba'quba Adhamia Baladrooz Adhamia Baladrooz Kadhimia Kadhimia JANUARY TO MAY CRISIS KarkhAl Resafa Ramadi Ramadi KarkhAl Resafa 1 Abu Ghraib Abu Ghraib BAGHDADMada'in BAGHDADMada'in ANBAR Falluja ANBAR Falluja Mahmoudiya Mahmoudiya Badra Badra 2% 1% Al-Azezia Al-Azezia Al-Suwaira Al-Suwaira Al-Musayab Al-Musayab 21% Al-Mahawil -

Three Years of Post-Samarra Displacement in Iraq

IOM EMERGENCY NEEDS ASSESSMENTS FEBRUARY 22, 2009: THREE YEARS OF POST-SAMARRA DISPLACEMENT IN IRAQ I. POPULATION DISPLACEMENT AND RETURN IN IRAQ Three years after a severe wave of sectarian violence began, returns are increasing and new displacement is rare. Iraqis look to rebuilding their lives facing an uncertain security future. On 22 February 2006, the bombing of the Al-Askari Mosque in Samarra triggered escalating sectarian violence that drastically changed the cause and INSIDE: scale of displacement in Iraq, both to locations inside Iraq and to locations Displacement/ 1 abroad. Since February 2006, more than 1,600,000 Iraqis (270,000 Return Summary families) have been displaced - approximately 5.5% of the total Post February 2006 population. Of these 270,000 families, IOM monitoring teams have Profile with identified and assessed 209,402 (an estimated 1,256,412 individuals), or 80% Numbers, 2 of the total post-Samarra displacement population. Identities, Locations, Origins These assessments, illustrated in this report, reveal the demographic Return potentials composition and geographic journeys of the IDP populations remaining in Humanitarian displacement, as well as detail the overwhelming needs for basics such as Needs & Response adequate shelter, sufficient food, clean water, and access to employment. Even as security appears to improve and displacement slows, Iraqi IDPs face threats of eviction and live in precarious environments, with the possibility of violence still a present worry. IOM’s assessments of IDP families’ intentions reveal that many wish to return home and may do so if conditions permit, especially that of security. Others wish to begin new lives in their places of displacement or other locations. -

The Central Islamic Lands

77 THEME The Central Islamic 4 Lands AS we enter the twenty-first century, there are over 1 billion Muslims living in all parts of the world. They are citizens of different nations, speak different languages, and dress differently. The processes by which they became Muslims were varied, and so were the circumstances in which they went their separate ways. Yet, the Islamic community has its roots in a more unified past which unfolded roughly 1,400 years ago in the Arabian peninsula. In this chapter we are going to read about the rise of Islam and its expansion over a vast territory extending from Egypt to Afghanistan, the core area of Islamic civilisation from 600 to 1200. In these centuries, Islamic society exhibited multiple political and cultural patterns. The term Islamic is used here not only in its purely religious sense but also for the overall society and culture historically associated with Islam. In this society not everything that was happening originated directly from religion, but it took place in a society where Muslims and their faith were recognised as socially dominant. Non-Muslims always formed an integral, if subordinate, part of this society as did Jews in Christendom. Our understanding of the history of the central Islamic lands between 600 and 1200 is based on chronicles or tawarikh (which narrate events in order of time) and semi-historical works, such as biographies (sira), records of the sayings and doings of the Prophet (hadith) and commentaries on the Quran (tafsir). The material from which these works were produced was a large collection of eyewitness reports (akhbar) transmitted over a period of time either orally or on paper. -

Investment Map of Iraq 2016

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investment Map of Iraq 2016 Dear investor: Investment opportunities found in Iraq today vary in terms of type, size, scope, sector, and purpose. the door is wide open for all investors who wish to hold investment projects in Iraq,; projects that would meet the growing needs of the Iraqi population in different sectors. Iraq is a country that brims with potential, it is characterized by its strategic location, at the center of world trade routes giving it a significant feature along with being a rich country where I herby invite you to look at Iraq you can find great potentials and as one of the most important untapped natural resources which would places where untapped investment certainly contribute in creating the decent opportunities are available in living standards for people. Such features various fields and where each and characteristics creates favorable opportunities that will attract investors, sector has a crucial need for suppliers, transporters, developers, investment. Think about the great producers, manufactures, and financiers, potentials and the markets of the who will find a lot of means which are neighboring countries. Moreover, conducive to holding new projects, think about our real desire to developing markets and boosting receive and welcome you in Iraq , business relationships of mutual benefit. In this map, we provide a detailed we are more than ready to overview about Iraq, and an outline about cooperate with you In order to each governorate including certain overcome any obstacle we may information on each sector. In addition, face.