Arxiv:1508.06383V1 [Quant-Ph] 26 Aug 2015 Bles at Room Temperature [19–21], Bose-Einstein Conden- Is So: There Are Two Possibilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

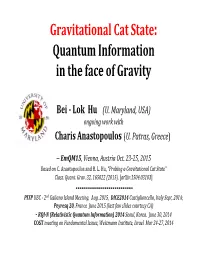

Gravitational Cat State: Quantum Information in the Face of Gravity

Gravitational Cat State: Quantum Information in the face of Gravity Bei ‐ Lok Hu (U. Maryland, USA) ongoing work with Charis Anastopoulos (U. Patras, Greece) ‐‐ EmQM15, Vienna, Austria Oct. 23‐25, 2015 Based on C. Anastopoulos and B. L. Hu, “Probing a Gravitational Cat State” Class. Quant. Grav. 32, 165022 (2015). [arXiv:1504.03103] ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ PITP UBC ‐ 2nd Galiano Island Meeting, Aug. 2015, DICE2014 Castiglioncello, Italy Sept, 2014; Peyresq 20, France June 2015 (last few slides courtesy CA) ‐ RQI‐N (Relativistic Quantum Information) 2014 Seoul, Korea. June 30, 2014 COST meeting on Fundamental Issues, Weizmann Institute, Israel Mar 24‐27, 2014 Three elements: Q I G Quantum, Information and Gravity • Quantum Quantum Mechanics Quantum Field Theory Schroedinger Equation | | micro •Gravity Newton Mechanics General Relativity | Macro • GR+QFT= Semiclassical Gravity (SCG) • Laboratory conditions: | Strong Field Conditions: Weak field, nonrelativistic limit: | Early Universe, Black Holes Newton Schrodinger Eq (NSE) | Semiclassical Einstein Eq Two layers of theoretical construct: (1 small surprise, 1 observation) 1) Small Surprise?: NSE for single or multiple particles is not derivable from known physics C. Anastopoulos and B. L. Hu, Problems with the Newton‐Schrödinger Equations New J. Physics 16 (2014) 085007 [ arXiv:1403.4921] Newton‐Schrodinger Eq <=/= Semiclassical Einstein Eqn of Semiclassical Gravity (this nomenclature is preferred over Mller‐Rosenfeld Eq) Semiclassical Gravity Semiclassical Einstein Equation (Moller-Rosenfeld): -

Metrological Complementarity Reveals the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Paradox

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22353-3 OPEN Metrological complementarity reveals the Einstein- Podolsky-Rosen paradox ✉ Benjamin Yadin1,2,5, Matteo Fadel 3,5 & Manuel Gessner 4,5 The Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) paradox plays a fundamental role in our understanding of quantum mechanics, and is associated with the possibility of predicting the results of non- commuting measurements with a precision that seems to violate the uncertainty principle. 1234567890():,; This apparent contradiction to complementarity is made possible by nonclassical correlations stronger than entanglement, called steering. Quantum information recognises steering as an essential resource for a number of tasks but, contrary to entanglement, its role for metrology has so far remained unclear. Here, we formulate the EPR paradox in the framework of quantum metrology, showing that it enables the precise estimation of a local phase shift and of its generating observable. Employing a stricter formulation of quantum complementarity, we derive a criterion based on the quantum Fisher information that detects steering in a larger class of states than well-known uncertainty-based criteria. Our result identifies useful steering for quantum-enhanced precision measurements and allows one to uncover steering of non-Gaussian states in state-of-the-art experiments. 1 School of Mathematical Sciences and Centre for the Mathematics and Theoretical Physics of Quantum Non-Equilibrium Systems, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK. 2 Wolfson College, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. 3 Department of Physics, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland. 4 Laboratoire Kastler Brossel, ENS-Université PSL, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, Collège de France, Paris, France. 5These authors contributed equally: Benjamin Yadin, Matteo Fadel, ✉ Manuel Gessner. -

![Arxiv:1610.07046V2 [Quant-Ph] 5 Aug 2017](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4358/arxiv-1610-07046v2-quant-ph-5-aug-2017-1194358.webp)

Arxiv:1610.07046V2 [Quant-Ph] 5 Aug 2017

Cat-state generation and stabilization for a nuclear spin through electric quadrupole interaction Ceyhun Bulutay1, ∗ 1Department of Physics, Bilkent University, Ankara 06800, Turkey (Dated: July 10, 2018) Spin cat states are superpositions of two or more coherent spin states (CSSs) that are distinctly separated over the Bloch sphere. Additionally, the nuclei with angular momenta greater than 1/2 possess a quadrupolar charge distribution. At the intersection of these two phenomena, we devise a simple scheme for generating various types of nuclear spin cat states. The native biaxial electric quadrupole interaction that is readily available in strained solid-state systems plays a key role here. However, the fact that built-in strain cannot be switched off poses a challenge for the stabilization of target cat states once they are prepared. We remedy this by abruptly diverting via a single rotation pulse the state evolution to the neighborhood of the fixed points of the underlying classical Hamiltonian flow. Optimal process parameters are obtained as a function of electric field gradient biaxiality and nuclear spin angular momentum. The overall procedure is seen to be robust under 5% deviations from optimal values. We show that higher level cat states with four superposed CSS can also be formed using three rotation pulses. Finally, for open systems subject to decoherence we extract the scaling of cat state fidelity damping with respect to the spin quantum number. This reveals rates greater than the dephasing of individual CSSs. Yet, our results affirm that these cat states can preserve their fidelities for practically useful durations under the currently attainable decoherence levels. -

Frontiers of Quantum and Mesoscopic Thermodynamics 14 - 20 July 2019, Prague, Czech Republic

Frontiers of Quantum and Mesoscopic Thermodynamics 14 - 20 July 2019, Prague, Czech Republic Under the auspicies of Ing. Miloš Zeman President of the Czech Republic Jaroslav Kubera President of the Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic Milan Štˇech Vice-President of the Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic Prof. RNDr. Eva Zažímalová, CSc. President of the Czech Academy of Sciences Dominik Cardinal Duka OP Archbishop of Prague Supported by • Committee on Education, Science, Culture, Human Rights and Petitions of the Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic • Institute of Physics, the Czech Academy of Sciences • Department of Physics, Texas A&M University, USA • Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands • College of Engineering and Science, University of Detroit Mercy, USA • Quantum Optics Lab at the BRIC, Baylor University, USA • Institut de Physique Théorique, CEA/CNRS Saclay, France Topics • Non-equilibrium quantum phenomena • Foundations of quantum physics • Quantum measurement, entanglement and coherence • Dissipation, dephasing, noise and decoherence • Many body physics, quantum field theory • Quantum statistical physics and thermodynamics • Quantum optics • Quantum simulations • Physics of quantum information and computing • Topological states of quantum matter, quantum phase transitions • Macroscopic quantum behavior • Cold atoms and molecules, Bose-Einstein condensates • Mesoscopic, nano-electromechanical and nano-optical systems • Biological systems, molecular motors and -

Schrödinger Cat States in Circuit

Schr¨odinger Cat States in Circuit QED Lectures presented at the Les Houches Summer School, Session CVII–Current Trends in Atomic Physics, July 2016. S. M. Girvin Yale Quantum Institute PO Box 208334 New Haven, CT 06520-8263 USA arXiv:1710.03179v1 [quant-ph] 9 Oct 2017 1 Preface The last 15 years have seen spectacular experimental progress in our ability to create, control and measure the quantum states of superconducting ‘artificial atoms’ (qubits) and microwave photons stored in resonators. In addition to being a novel testbed for studying strong-coupling quantum electrodynamics in a radically new regime, ‘circuit QED,’ defines a fundamental architecture for the creation of a quantum computer based on integrated circuits with semiconductors replaced by superconductors. The artificial atoms are based on the Josephson tunnel junction and their relatively large size ( mm) means that the couple extremely strongly to individual microwave pho- tons.∼ This strong coupling yields very powerful state-manipulation and measurement capabilities, including the ability to create extremely large (> 100 photon) ‘cat’ states and easily measure novel quantities such as the photon number parity. These new ca- pabilities have enabled a highly successful scheme for quantum error correction based on encoding quantum information in Schr¨odinger cat states of photons. Acknowledgements The ideas described here represent the collaborative efforts of many students, postdocs and faculty colleagues who have been members of the Yale quantum information team over the past 15 years. The author is especially grateful for the opportunities he has had to collaborate with long-time friends and colleagues Michel Devoret, Leonid Glazman, Liang Jiang and Rob Schoelkopf as well as frequent visitor, Mazyar Mirrahimi. -

Nonlinear Entanglement and Its Application to Generating Cat States

week ending PRL 114, 100403 (2015) PHYSICAL REVIEW LETTERS 13 MARCH 2015 Nonlinear Entanglement and its Application to Generating Cat States Y. Shen,1,2,3 S. M. Assad,2 N. B. Grosse,2 X. Y. Li,1 M. D. Reid,4 and P. K. Lam1,2,* 1College of Precision Instrument and Optoelectronics Engineering, Key Laboratory of Optoelectronics Information Technology of Ministry of Education, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China 2Centre for Quantum Computation and Communication Technology, Research School of Physics and Engineering, Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 0200, Australia 3Department of Physics, The National University of Defense Technology, Changsha 410073, China 4Centre for Atom Optics and Ultrafast Spectroscopy, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Victoria 3122, Australia (Received 21 May 2014; revised manuscript received 21 September 2014; published 10 March 2015) The Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) paradox, which was formulated to argue for the incompleteness of quantum mechanics, has since metamorphosed into a resource for quantum information. The EPR entanglement describes the strength of linear correlations between two objects in terms of a pair of conjugate observables in relation to the Heisenberg uncertainty limit. We propose that entanglement can be extended to include nonlinear correlations. We examine two driven harmonic oscillators that are coupled via third-order nonlinearity can exhibit quadraticlike nonlinear entanglement which, after a projective measurement on one of the oscillators, collapses the other into a cat state of tunable size. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.100403 PACS numbers: 03.65.Ud, 03.67.Mn, 42.50.Dv, 42.65.Lm The argument developed in 1935 by Einstein, Podolsky, can lead to a form of nonlinear entanglement that demon- and Rosen (EPR) [1] illuminated a striking inconsistency: strates steerability by satisfying an equivalent nonlinear quantum mechanics, as it stood then and still stands today, EPR criterion. -

A Hyper-Entangled Ten-Qubit Schrödinger Cat State

Experimental demonstration of a hyper‐entangled ten‐qubit Schrödinger cat state Wei-Bo Gao1, Chao-Yang Lu1, Xing-Can Yao1, Ping Xu1, Otfried Gühne2,3, Alexander Goebel4, Yu-Ao Chen1,4, Cheng-Zhi Peng1, Zeng-Bing Chen1, Jian-Wei Pan1,4,* (1) Hefei National Laboratory for Physical Sciences at Microscale and Department of Modern Physics, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui 230026, P.R. China; ( 2) Institut für Quantenoptik und Quanteninformation, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Technikerstraβe 21A, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria; (3) Institut für Theoretische Physik, Universität Innsbruck, Technikerstraβe 25, A–6020 Innsbruck, Austria. (4) Physikalisches Institut, Universität Heidelberg, Philosophenweg 12, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany. * email: jian-wei.pan(at)physi.uni-heidelberg.de Abstract: Coherent manipulation of an increasing number of qubits for the generation of entangled states has been an important goal and benchmark in the emerging field of quantum information science. The multiparticle entangled states serve as physical resources for measurement-based quantum computing (1) and high-precision quantum metrology (2,3). However, their experimental preparation has proved extremely challenging. To date, entangled states up to six (4), eight (5) atoms, or six photonic qubits (6) have been demonstrated. Here, by exploiting both the photons' polarization and momentum degrees of freedom, we report the creation of hyper-entangled six-, eight-, and ten-qubit Schrödinger cat states. We characterize the cat states by evaluating their fidelities and detecting the presence of genuine multi-partite entanglement. Small modifications of the experimental setup will allow the generation of various graph states up to ten qubits. Our method provides a shortcut to expand the effective Hilbert space, opening up interesting applications such as quantum-enhanced super-resolving phase measurement, graph-state generation for anyonic simulation (7) and topological error correction (8,9), and novel tests of nonlocality with hyper-entanglement (10,11) . -

Quantum Mechanics and Reality

Quantum mechanics and reality Margaret Reid Centre for Atom Optics and Ultrafast Spectroscopy Swinburne University of Technology Melbourne, Australia Thank you! Outline • Non-locality, reality and quantum mechanics: Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) paradox Schrodinger cat Bell’s theorem: Bell inequalities Entanglement and Steering Experiments • Macro-scopic reality EPR and Schrodinger cat Genuine multipartite nonlocality: GHZ states CV EPR Entangled atoms Macroscopic realism: Leggett- Garg inequalities EPR paradox 1935 • Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen argument • Einstein was unhappy about quantum mechanics • Believed it was correct but incomplete: Quantum mechanics and reality 1 Ψ = x + x ʹ 2 ( ) • Principle of superposition • Not one or the other until measured: Dirac € • Cannot view things as existing until they are measured? • But why would this be a problem? Quantum mechanics and reality 1 Ψ = x + x ʹ 2 ( ) • You might argue…. • Fundamental indeterminacy in nature? Heisenberg microscope € • Interaction of a microscopic system with any measurement apparatus? • But this is not a resolution 2 problems put forward Problem 1: Schrodinger’s cat 1935 1 Ψ = dead + alive 2 ( ) • Quantum mechanics predicts macroscopic superpositions • How does “not one or the other until measured” work for macroscopic€ superpositions? Dead and alive? Diosi/ Penrose theories propose collapse mechanism for massive objects Diosi Penrose decoherence time for massive object m Problem 2: Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) paradox 1935 X! Nonlocal measurements B A Entanglement -

![Arxiv:2009.00128V2 [Cond-Mat.Mes-Hall] 11 Sep 2020 Ments, Owing Partly to Its Extremely Low Magnetic Dis- Sipation [24]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2076/arxiv-2009-00128v2-cond-mat-mes-hall-11-sep-2020-ments-owing-partly-to-its-extremely-low-magnetic-dis-sipation-24-2692076.webp)

Arxiv:2009.00128V2 [Cond-Mat.Mes-Hall] 11 Sep 2020 Ments, Owing Partly to Its Extremely Low Magnetic Dis- Sipation [24]

Spin cat states in a ferromagnetic insulator Sanchar Sharma,1 Victor A. S. V. Bittencourt,1 Alexy D. Karenowska,2 and Silvia Viola Kusminskiy1, 3 1Max Planck Institute for the Science of Light, Staudtstraße 2, 91058 Erlangen, Germany 2Clarendon Laboratory, Department of Physics, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3PU, United Kingdom 3Department of Physics, University Erlangen-Nürnberg, Staudtstraße 7, 91058 Erlangen, Germany Generating non-classical states in macroscopic systems is a long standing challenge. A promising platform in the context of this quest are novel hybrid systems based on magnetic dielectrics, where photons can couple strongly and coherently to magnetic excitations, although a non-classical state therein is yet to be observed. We propose a scheme to generate a magnetization cat state, i.e. a quantum superposition of two distinct magnetization directions, using a conventional setup of a macroscopic ferromagnet in a microwave cavity. Our scheme uses the ground state of an ellipsoid shaped magnet, which displays anisotropic quantum fluctuations akin to a squeezed vacuum. The magnetization collapses to a cat state by either a single-photon or a parity measurement of the microwave cavity state. We find that a cat state with two components separated by ∼ 5~ is feasible and briefly discuss potential experimental setups that can achieve it. Introduction: The concept of superposition is a cor- (a) MeasureMeasurement nerstone of quantum theory, a paradigmatic example of which is a ‘cat state’ referring to, loosely speaking, a Microwave system which exists in a quantum superposition of two H0 quasi-classical states. Besides their important histori- M B cal link to Schrödinger’s famous gedanken experiment, − · y z their insensitivity to particle loss noise [1] means that z y Magnetization cat states find useful application as carriers of informa- tion (qubits) in quantum computation [2–4] or as sensors in quantum metrological tasks [5–8]. -

Macroscopic Quantum Superposition States and Wigner Functions on the Sphere

PHYSICAL REVIEW A VOLUME 60, NUMBER 3 SEPTEMBER 1999 Finite Kerr medium: Macroscopic quantum superposition states and Wigner functions on the sphere Sergey M. Chumakov,1 Alejandro Frank,2 and Kurt Bernardo Wolf3 1Departamento de Fı´sica, Universidad de Guadalajara, Corregidora 500, 44420 Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico 2Instituto de Ciencias Nucleares and Centro de Ciencias Fı´sicas, Universidad Nacional Auto´nomadeMe´xico, Apartado Postal 48-3, 62251 Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico 3Centro de Ciencias Fı´sicas Universidad Nacional Auto´nomadeMe´xico, Apartado Postal 48-3, 62251 Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico ͑Received 30 September 1997; revised manuscript received 20 November 1998͒ We propose a spin model which exhibits the main properties of the Kerr medium. The description of the model uses a recently generalized quasiprobability distribution ͑Wigner function͒ for the SU͑2͒ group. This function is naturally defined on the sphere, which plays the role of phase space for the spin system. Our model leads to macroscopic quantum superposition states on the sphere. ͓S1050-2947͑99͒06908-5͔ PACS number͑s͒: 03.65.Bz, 42.50.Fx I. INTRODUCTION ͑ ͒ ͓ ͔ ϱ distribution on the SU 2 group 6 . In the limit l˜ , when the su͑2͒ algebra of spin operators contracts to the To stress the intriguing implications of the quantum su- Heisenberg-Weyl algebra of boson operators, the sphere perposition of states which are macroscopically different, opens to the phase plane and the model coincides with the Schro¨dinger ͓1͔ proposed quantum states with the following quantum harmonic oscillator or, through a renormalization, structure: with the common Kerr medium. After a brief review of the Kerr dynamics in Sec. -

Quantum Harmonic Oscillator State Synthesis and Analysis∗

Quantum harmonic oscillator state synthesis and analysis∗ W. M. Itano, C. Monroe, D. M. Meekhof, D. Leibfried, B. E. King, and D. J. Wineland Time and Frequency Division National Institute of Standards and Technology Boulder, Colorado 80303 USA ABSTRACT We laser-cool single beryllium ions in a Paul trap to the ground (n = 0) quantum harmonic oscillator state with greater than 90% probability. From this starting point, we can put the atom into various quantum states of motion by application of optical and rf electric fields. Some of these states resemble classical states (the coherent states), while others are intrinsically quantum, such as number states or squeezed states. We have created entangled position and spin superposition states (Schr¨odinger cat states), where the atom’s spatial wavefunction is split into two widely separated wave packets. We have developed methods to reconstruct the density matrices and Wigner functions of arbitrary motional quantum states. These methods should make it possible to study decoherence of quantum superposition states and the transition from quantum to classical behavior. Calculations of the decoherence of superpositions of coherent states are presented. Keywords: quantum state generation, quantum state tomography, laser cooling, ion storage, quantum computation 1. INTRODUCTION In a series of studies we have prepared single, trapped, 9Be+ ions in various quantum harmonic oscillator states and performed measurements on those states. In this article, we summarize some of the results. Further details are given in the original reports.1–5 The quantum states of the simple harmonic oscillator have been studied since the earliest days of quantum mechanics. -

Teleportation of a Schr¨Odinger's-Cat State Via Satellite-Based

Teleportation of a Schrodinger’s-Cat¨ State via Satellite-based Quantum Communications Hung Do, Robert Malaney and Jonathan Green Abstract—The Schrodinger’s-cat¨ state is created from the The CV teleportation macroscopic superposition of coherent states and is well-known channel CV to be a useful resource for quantum information processing Entanglement protocols. In order to extend such protocols to a global scale, The state to be # % we study the continuous variable (CV) teleportation of the teleported # $ cat state via a satellite in low-Earth-orbit. Past studies have shown that the quantum character of the cat state can be % Dis place preserved after CV teleportation, even when taking into account )* $ the detector efficiency. However, the channel transmission loss has not been taken into consideration. Traditionally, optical ' ( fibers with fixed attenuation are used as teleportation channels. Our results show that in such a setup, the quantum character !" of the cat state is lost after 5dB of channel loss. We then Alice Bob investigate the free-space channel between the Earth and a satellite, where the loss is caused by atmospheric turbulence. For Fig. 1: In the hybrid scheme, the CV entanglement A − B is used as a a down-link channel of less than 500km and 30dB of loss, we teleportation channel. The channels have transmissivity TA and TB . The find that the teleported state preserves higher fidelity relative input state Win is teleported from Alice to Bob, resulting in the output to a fixed attenuation channel. The results in this work will Wout. be important for deployments over Earth-Satellite channels of protocols dependent on cat-state qubits.