Insert Proposal Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pretoria East 18515/16-4-21

Pretoria East 18515/16-4-21 QUALITY USED VEHICLES AWESOME DEALS APRIL 30, 2021 • www.rekord.co.za • 012-842-0300 012 329 0730 | www.autoplatinum.co.za Visit our website for breaking More arrests expected Covid-19 patient in Funding for emergency local, national and international news. for highway spike traps 2 ICU for seven weeks 3 and social services 4 rekordeast.co.za Sole survivor key to deaths ‘It is believed the group had gone out for drinks the Friday night when they later took the party back to Kleynhans’ entertainment house.’ Noxolo Sibiya under the impression that it was just another day in paradise and they had just passed The only survivor to a tragedy that saw three out,” he said. people die at an “extreme house of pleasure” “We are also looking at poisoning.” in Menlo Park can help investigators piece Bolhuis said the house was defi nitely used together the mysterious deaths that took for a trade of some sort in the fi eld of sex place there a week ago. and drugs, which has led to him labelling the Investigators are hoping that the woman property as “the house of extreme pleasure”. could help shed light on the circumstances He said the house was under surveillance that led to the death of a well-known and this was mostly done to record some of Pretoria property developer, Theo Kleynhans the sexual acts that were performed there. (60), and two of his colleagues at the house “Kleynhans fi lmed everyone there, on Hazelwood Street. especially the sexual behaviours. -

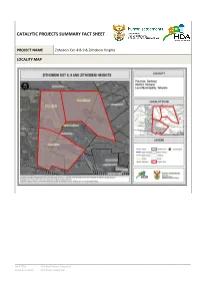

Catalytic Projects Summary Fact Sheet

CATALYTIC PROJECTS SUMMARY FACT SHEET PROJECT NAME Zithobeni Ext. 8 & 9 & Zithobeni Heights LOCALITY MAP _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ April 2016 Technical Report Completed September 2016 Fact Sheet Completed CATALYTIC PROJECTS SUMMARY FACT SHEET Zithobeni Ext. 8 & 9 PROJECT NAME LAND CONDITION Greenfield/Brownfield/Infill Zithobeni Heights DEVELOPER City of Tshwane/PDOHS CLASSIFICATION Low Risk PROVINCE Gauteng MUNICIPALITY City of Tshwane MM The development areas are located to the east and north of the existing Zithobeni Township, approximately 3 km north-west of Bronkhorstspruit about 67.3 km east of the Pretoria CBD, in CoT Region 7. PROJECT DESCRIPTION Combined the Zithobeni developments proposes to deliver approximately 7,742 housing units - distributed as 1,899 units, 1,918 units and 3,925 units respectively for Zithobeni Extension 8, Zithobeni Extension 9, and Zithobeni Heights. MAIN ECONOMIC Manufacturing and financial / business services are the main economic drivers within the DRIVER(S) larger Bronkhorstspruit area. DEVELOPMENT Under implementation – project phased due to budgetary constraints STATUS NUMBER OF 7 742 HOUSING PROJECT DURATION 10 years OPPORTUNITIES PROPOSED ADJUSTED NO. OF PROPOSED ADJUSTED TBC 10 - 12 years HOUSING PROJECT DURATION OPPORTUNITIES ESTIMATE PROJECT POTENTIAL JOB DEVELOPMENT R 2 822 450.00 ± 3,176 OPPORTUNITIES COST _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Region 7 RSDF Doc 2018

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS _________________________________________________________________________________________ ABBREVIATIONS i GLOSSARY OF TERMS iv 2.5 ENVIRONMENTAL STRUCTURING CONCEPT 27 2.5.1 Heritage and Cultural Sites 27 PART ONE: INTRODUCTION 1 2.5.2 Open Space and Conservation Areas 27 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 2.5.3 Rural Management 29 1.2 LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 1 1.3 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 2 PART THREE: REGIONAL ANALYSIS 32 1.4 THE USE OF THIS DOCUMENT 2 3.1 LOCALITY 32 PART TWO: METROPOLITAN CONTEXT 4 3.2 AREA 33 3.3 DEMOGRAPHIC INFO 33 2.1 POLICY FRAMEWORK 4 3.4 WARD PRIORITIES FOR 2015/16 34 2.1.1 National Development Plan; 2014 5 3.5 REGIONAL CHARACTERISTICS 35 2.1.2 The Comprehensive Rural Development Programme, 2009 5 3.6 STRUCTURING ELEMENTS 35 2.1.3 Gauteng Spatial Development Framework: 2030 7 3.7 ECONOMIC BASE 36 2.1.4 The Gauteng Rural Development Plan: 2014 9 2.1.5 Gauteng 25 Year Integrated Transport Master Plan: 2013 10 3.8 PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT 36 2.1.6 The Spatial Vision Of The City 11 3.8.1 Natural Structuring Elements 36 2.1.7 Integrated Development Plan Revision 2017/2021: 12 3.8.2 Strategic Land Uses 37 2.1.8 Metropolitan Spatial Development Framework 13 3.8.3 Nodes 37 2.1.9 Tshwane Integrated Rapid Public Transport Network (IRTPN) 3.8.4 Linear Activity Areas 37 Strategy 13 3.8.5 Residential Characteristics 37 2.1.10 Tshwane Comprehensive Integrated Transport Plan (CITP) 14 3.8.6 Movement And Transport System 38 3.8.7 Service Infrastructure 38 2.2 THE CITY STRUCTURE 15 2.2.1 Hierarchy Of Nodes 15 3.9 KEY ISSUES AND -

Region 5: Regional Integrated Development Plan 2014-15

REGION 5: REGIONAL INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2014-15 1 REGIONAL INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN: REGION 5 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 7 2 SITUATIONAL OVERVIEW ............................................................................... 8 2.1 Socio-Economic Profile ...................................................................................... 9 2.1.1 Population Size and Composition ................................................................ 9 2.1.2 Levels of Education ................................................................................... 10 2.1.3 Employment ............................................................................................... 11 2.1.4 Accommodation ......................................................................................... 12 2.2 Spatial Characteristics ..................................................................................... 13 2.2.1 Main Components ..................................................................................... 13 2.2.2 Regional Characteristics ............................................................................ 14 2.3 SWOT Analysis ................................................................................................ 15 3 STRATEGIC DIRECTION ................................................................................ 16 3.1 City of Tshwane Vision and Mission ................................................................ -

Gauteng No Fee Schools 2021

GAUTENG NO FEE SCHOOLS 2021 NATIONAL NAME OF SCHOOL SCHOOL PHASE ADDRESS OF SCHOOL EDUCATION DISTRICT QUINTILE LEARNER EMIS 2021 NUMBERS NUMBER 2021 700910011 ADAM MASEBE SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY 110, BLOCK A, SEKAMPANENG, TEMBA, TEMBA, 0407 TSHWANE NORTH 1 1056 700400393 ALBERTINA SISULU PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 1250, SIBUSISO, KINGSWAY, BENONI, BENONI, 1501 EKURHULENI NORTH 1 1327 24936, CNR ALEKHINE & STANTON RD, PROTEA SOUTH, 700121210 ALTMONT TECHNICAL HIGH SCHOOL SECONDARY JOHANNESBURG CENTRAL 1 1395 SOWETO, JOHANNESBURG, 1818 2544, MANDELA & TAMBO, BLUEGUMVIEW, DUDUZA, NIGEL, 700350561 ASSER MALOKA SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY GAUTENG EAST 1 1623 1496 2201, MAMASIYANOKA, GA-RANKUWA VIEW, GA-RANKUWA, 700915064 BACHANA MOKWENA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY TSHWANE WEST 1 993 PRETORIA, 0208 22640, NGUNGUNYANE AVENUE, BARCELONA, ETWATWA, 700400277 BARCELONA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY GAUTENG EAST 1 1809 BENONI, 1519 577, KAALPLAATS, BARRAGE, VANDERBIJLPARK, 700320291 BARRAGE PRIMARY FARM SCHOOL PRIMARY SEDIBENG WEST 1 317 JOHANNESBURG, 1900 11653, LINDANI STREET, OLIEVENHOUTBOSCH, CENTURION, 700231522 BATHABILE PRIMARY FARM SCHOOL PRIMARY TSHWANE SOUTH 1 1541 PRETORIA, 0175 700231530 BATHOKWA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 1, LEPHORA STREET, SAULSVILLE, PRETORIA, PRETORIA, 0125 TSHWANE SOUTH 1 1081 25, OLD PRETORIA ROAD BAPSFONTEIN, BAPSFONTEIN, 700211276 BEKEKAYO PRIMARY FARM SCHOOL PRIMARY EKURHULENI NORTH 1 139 BENONI, BENONI, 1510 2854, FLORIDA STREET, BEVERLY HILLS, EVATON WEST, 700320937 BEVERLY HILLS SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY SEDIBENG WEST 1 1504 -

TSH City of Tshwane Draft BEPP 2015-16

BUILT ENVIRONMENT PERFORMANCE PLAN (BEPP) 2015/16 First Draft November 2014 City Planning and Development Department 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS A INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 2 LIST OF REFERENCE DOCUMENTS 3 B STRATEGIC REVIEW OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT 4 B1 CURRENT PERFORMANCE OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT 4 B2 ECONOMIC INFRASTRUCTURE 21 B3 BASIC INFRASTRUCTURE REVIEW 39 B4 RESIDENTIAL INFRASTRUCTURE REVIEW 73 B5 COMMUNITY INFRASTRUCTURE REVIEW 154 B6 TRANSPORTATION REVIEW 161 B7 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT REVIEW 176 B8 IMPACT OF SECTOR REVIEWS ON SPATIAL FORM 181 C STRATEGIES AND PROGRAMMES 181 C1 LONG TERM VISION 181 C2 THE SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY OF THE MUNICIPALITY 186 C3 OVERVIEW OF AREA-BASED INITIATIVES INCLUDING CATALYTIC PROJECTS 193 C4 IDENTIFICATION OF URBAN NETWORK, INTEGRATION ZONES AND HUBS 225 D OUTCOMES AND OUTPUTS 229 E INSTITUTIONAL AND FINANCIAL ARRANGMENTS 229 1 INTRODUCTION The City of Tshwane Draft BEPP 2015/2016 dated 03 November 2014 is submitted in line with the BEPP Guidance Note 2015/16-2017/18. It is hereby submitted that in terms of the Council Approved IDP Process Plan 2015/2016, a comprehensive BEPP 2015/2016 will be submitted once the draft Capital Budget has been finalised in January 2015. The Final Draft will be submitted together with the Draft IDP and Capex 15_16 to the Mayoral Committee during the period March-May 2015. This submission provides the city’s in context approach towards spatial targeting with primary focus on the movement system as the key spatial restructuring element of the built environment. Other built environment restructuring components will be incorporated in the next submission. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Africa Innovation Summit (AIS) Satellite Event “Innovation

Private Bag X894, Pretoria, 0001 Tel.: +27 (0) 12 843 6379 Fax: +27 (0) 12 843 6868 www.dst.gov.za Africa Innovation Summit (AIS) Satellite Event “Innovation – Addressing Africa’s Challenges” Date: 06–08 June 2018 Venue: The Venue, Menlyn Pretoria, South Africa 1 Information package for participants 1. Immigration requirements All participants travelling to Johannesburg, South Africa, should have a valid passport. It is strongly recommended that delegates who require visa to enter South Africa should apply for them at the South African Consulates in their respective countries. 2. Travel (Airport and Ground transport) Arrival will be at the OR Tambo International Airport in Johannesburg, South Africa. Upon arrival, ground transport will be provided by EZ Shuttle. EZ Shuttle drivers will greet you at the airport with your name and/or surname on their boards. The drivers will be wearing green ties with black suits. On the last day of the event (June 8th) all those traveling to the Airport are advised to check out with all their luggage in the morning. Their luggage will be safely stored in a locked area at the conference venue. The shuttle will pick up all those traveling to the Airport at the summit venue NOT at the hotel where you are booked. Should you miss the shuttle and consequently miss your flight, the Department will not be held liable for any additional costs incurred for rebooking of flights. Please note that the EZ Shuttle will drop you at the OR Tambo International Airport at least two hours before your departure time. -

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC of SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA February Vol. 656 Pretoria, 14 2020 Februarie No. 43014 B LEGAL NOTICES WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER OPENBARE VERKOPE ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 43014 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 43014 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 14 FEBRUARY 2020 IMPORTANT NOTICE OF OFFICE RELOCATION Private Bag X85, PRETORIA, 0001 149 Bosman Street, PRETORIA Tel: 012 748 6197, Website: www.gpwonline.co.za URGENT NOTICE TO OUR VALUED CUSTOMERS: PUBLICATIONS OFFICE’S RELOCATION HAS BEEN TEMPORARILY SUSPENDED. Please be advised that the GPW Publications office will no longer move to 88 Visagie Street as indicated in the previous notices. The move has been suspended due to the fact that the new building in 88 Visagie Street is not ready for occupation yet. We will later on issue another notice informing you of the new date of relocation. We are doing everything possible to ensure that our service to you is not disrupted. As things stand, we will continue providing you with our normal service from the current location at 196 Paul Kruger Street, Masada building. Customers who seek further information and or have any questions or concerns are free to contact us through telephone 012 748 6066 or email Ms Maureen Toka at [email protected] or cell phone at 082 859 4910. -

Gauteng Province L Ii M P O P O Bela Bela Rathoke Watervaal

Gauteng Province L ii m p o p o Bela Bela Rathoke Watervaal Ramantsho Rhenosterkop Dam Pienaarsrivier Klipvoor Dam Moretele Ramokokastad Rust de Mbibane Winter Dam Makapanstad Moteti Vaalkop Carousel Dam Sun Hotel Jericho Ramotse Temba Mandela Village Rooikoppies Stinkwater New Hammanskraal Dam Winterveldt Eersterust N o rr tt h Moloto Verena W e s tt Mabopane Soshanguve 1 Kopanong Bospoort Dam Ga- Rankuwa Pyramid Pebble Hebron Estate City of Rock Golf Onverwacht Vlakfontein Bon Village Brits Rosslyn Tshwane Accord Roodeplaat Sable Hills The Dam Wonderboom Dam Waterfront Orchards Estate Refilwe 4 Akasia Montana Ekangala Marikana Baviaanspoort Cullinan Theresa Ekandustria Pretoria Wonderboom Park Mamelodi North Gezina Rethabiseng Hartebeespoortdam Meyerspark Rayton Mooinooi Pretoria Hatfield Kosmos Hartebeespoort 4 CBD Silver Buffelspoort Dam Atteridgeville Faerie Waterkloof Menlyn Lakes Olifantsnekdam Dam Brazaville Glen Zithobeni Premiermyn Zwartkop Waterkloof 4 Riamarpark Bronkhorstspruit Dam AFB 14 AFB Sunderland Moreleta Wierda Park Erusmus Ridge Park Mooikloof Rietvleidam Kungwini PeachTree Country Blair Centurion Irene Summer Rietvallei Estate Athol Place Olievenhoutbosch Mogale City Monaghan Diepsloot Bashewa Bronkhorstspruit Local Lanseria Informal Kosmosdal Dam Grand Municipality Central Tembisa 14 Halfway Magaliesburg Kyalami House Jukskei Fourways Muldersdrif Sunnnghill Park Ogies Birchleigh Zandspruit Modderfontein Mogale City of Kempton O.R. Tambo City Johannesburg Park CBD Internasional 12 Sandton Alexandra Delmas Cresta -

Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant

THE PROVINCE OF DIE PROVINSIE VAN UNITY DIVERSITY GAUTENG IN GAUTENG Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant Selling price • Verkoopprys: R2.50 Other countries • Buitelands: R3.25 PRETORIA Vol. 23 20 SEPTEMBER 2017 No. 232 20 SEPTEMBER 2017 PART 1 OF 2 We oil Irawm he power to pment kiIDc AIDS HElPl1NE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure ISSN 1682-4525 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 00232 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 452005 2 No. 232 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, 20 SEPTEMBER 2017 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. CONTENTS Gazette Page No. No. GENERAL NOTICES • ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS 1320 Town Planning and Townships Ordinance (15/1986): Erven 1882 and 1974, Kempton Park Extension 4 ........ 232 14 1320 Ordonnansie op Dorpsbeplanning en Dorpe (15/1986): Erwe 1882 en 1974, Kempton Park Uitbreiding 4....... 232 14 1323 City of Tshwane Land Use Management By-law, 2016: Erf 150, Eldoraigne ..................................................... 232 15 1323 Stad van Tshwane Grondgebruikbestuurs-verordening, 2016: Erf 150, Eldoraigne .......................................... 232 15 1324 City of Tshwane Land Use Management By-law, 2016: Erf 194, Valhalla ......................................................... 232 16 1324 Stad van Tshwane Grondgebruikbestuur-Verordening, 2016: Erf 194, Valhalla ................................................ 232 16 1325 Town Planning and Townships Ordinance, 1986: Erf 3219, Brackenhurst Extension 2 Township .................... 232 17 1325 Ordonnansie op Dorpsbeplanning en Dorpe, 1986: Erf 3219, Brackenhurst Uitbreiding 2 Dorpsgebied .......... -

124 2-5-2018 Gautliquor

THE PROVINCE OF DIE PROVINSIE VAN UNITY DIVERSITY GAUTENG IN GAUTENG Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant EXTRAORDINARY • BUITENGEWOON Selling price • Verkoopprys: R2.50 Other countries • Buitelands: R3.25 PRETORIA Vol. 24 2 MAY 2018 No. 124 2 MEI 2018 We oil Irawm he power to pment kiIDc AIDS HElPl1NE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure ISSN 1682-4525 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 00124 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 452005 2 No. 124 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, EXTRAORDINARY, 2 MAY 2018 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. CONTENTS GENERAL NOTICE No Page No 669 Gauteng Liqour Act, 2003 (Act No. 2 of 2003): Notice of applications for liquor licences in terms of section 24: Divided into the following regions: ............................................................................................................................................................. 10 Johannesburg ............................................................................................................................................................... 10 Tshwane ....................................................................................................................................................................... 23 Ekurhuleni