56. 'Other' Anthropologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greece, Bulgaria and Albania1 General Introduct

Translating Socio-Cultural Anthropology into Education Educational Anthropology and Anthropology of education in SE European countries: Greece, Bulgaria and Albania1 Ioannis Manos, Gerorgia Sarikoudi University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, Greece General Introduction Education System I. Greece The education system in Greece is under the central responsibility and supervision of the state administration, and more specifically, the Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs (MERRA). It consists of three levels: primary, secondary (divided in lower and upper-secondary), and tertiary (higher) education. 1. Overview of the Greek education system According to the Greek constitution, the Greek state is bound to provide all Greek citizens with access to free education at all levels of the state education system. The Greek education system2 consists of three levels: primary, secondary (divided in lower and upper-secondary), and higher (tertiary) education. a) Primary Education3 Primary education includes the pre-primary (kindergarten/‘παιδικός σταθμός’/paidikos stathmos) and the primary schools (‘δημοτικό’/dimotiko). Pre-primary education is compulsory4 and 1 DISCLAIMER: The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. 2 For a summary of the Greek education system, see, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national- policies/eurydice/content/greece_en 3 A non-compulsory early childhood education is provided to children from the age of 2 months to 4-years-old by municipal public institutions (Infant Centers, Infant/Child Centers and Child Centers) or private, pre-school education and care centers. -

We Want Europe in Nagorno-Karabakh

WE WANT EUROPE IN NAGORNO-KARABAKH This appeal was endorsed by the following public figures from across Europe: Frank Engel, Member of the European Parliament (Luxembourg) - Michèle Rivasi, Member of the European Parliament (France) - Aloys Kabanda, Author, survivor of the genocide of the Tutsi, Ibuka (Belgium) - Bart Staes, Member of the European Parliament (Belgium) - Jill Evans, Member of the European Parliament (United Kingdom) - Peter Niedermüller, Member of the European Parliament (Germany) - Benjamin Abtan, President of the European Grassroots Antiracist Movement - EGAM, Coordinator of the Elie Wiesel Network of Parliamentarians of Europe for the Prevention of Mass Atrocities and Genocides and against Genocide Denial (France) - Josep Maria Terricabras, Member of the European Parliament – (Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya) - Bernard Coulie, Professor and former Dean, the Catholic University of Louvain (Belgium) - Daniyel Demir, President of BDVAD, umbrella organization for Arameans in Germany - Dr Mark Levene, Reader in History at the University of Southampton (United Kingdom) - Dr Ruth Barnett, psychiatrist and writer (United Kingdom) - Dr. Tessa Hofmann, author and chairwoman of the human rights NGO Working Group "Recognition Against Genocide" (Germany) - Francisco Palacios Romeo, Professor of Constitutional Law, Faculty of Law, University of Zaragoza (Spain)- Frank de Boer, Federal Union of European Nationalities (FUEN) (Belgium) - Fredrik Malm, Member of Swedish Parliament, Federal Chairman of the Liberal Party of Sweden, Deputy -

Cultural Differences in a Globalizing World

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES IN A GLOBALIZING WORLD CULTURAL DIFFERENCES IN A GLOBALIZING WORLD BY MICHAEL MINKOV FOREWORD BY GEERT HOFSTEDE United Kingdom North America Japan India Malaysia China Emerald Group Publishing Limited Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley BD16 1WA, UK First edition 2011 Copyright r 2011 Emerald Group Publishing Limited Reprints and permission service Contact: [email protected] No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying issued in the UK by The Copyright Licensing Agency and in the USA by The Copyright Clearance Center. No responsibility is accepted for the accuracy of information contained in the text, illustrations or advertisements. The opinions expressed in these chapters are not necessarily those of the Editor or the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-85724-613-4 Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Howard House, Environmental Management System has been certified by ISOQAR to ISO 14001:2004 standards Awarded in recognition of Emerald’s production department’s adherence to quality systems and processes when preparing scholarly journals for print Contents Quotes vii Acknowledgements ix Foreword xi Introduction xv 1. The Study of Culture and its Origins 1 2. Major Cross-Cultural Studies 45 3. Industry versus Indulgence 51 4. Monumentalism versus Flexumility 93 5. Hypometropia versus Prudence 137 6. Exclusionism versus Universalism 179 7. A Cultural Map of the World 225 8. -

Kiril Avramov

Kiril Avramov Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies The University of Texas at Austin 2505 University Avenue, BUR 578 Austin, TX 78712 Phone: (512)-475-6145 [email protected] EDUCATION 2003-2008: Ph.D., Political Science (Република България Министерски съвет, ВАК, образователна и научна степен „Доктор“), University of Sofia, Bulgaria Degree: Ph.D. 4/08 Dissertation: Success Strategies of the Bulgarian Economic Elite 1990-2001. Supervisor: Prof. Alexander Tomov (Deputy PM of Bulgaria 1990-1991). (Public defense on 04/09/2008, unanimous pass, cum laude) – (Образователна и научна степен „Доктор “по научната специалност 05.11.02 „Политология “; тема: „Стратегии за успех на българския икономически елит (1990-2001) “Научна комисия 12, Протокол № 10 от 06.10.2008 г.) 2005- 2006: Central European University (CEU), Budapest, Hungary. Doctoral Support Program (DSP) at the Department of Political Science. (Full tuition scholarship from the University). Academic adviser: Prof. Nenad Dimitrijevic. 2001- 2002: M.A., Diplomacy & International Relations. Department of Political Science, New Bulgarian University, Sofia, Bulgaria. Thesis: “The Epidemic Infectious Disease as an Element of the Stability of the International Security” Academic adviser: Dr. Ivan Nachev. (Cum laude). 1995- 1999: B.A., Political Science, Gustavus Adolphus College, St. Peter, (MN), USA Department of Political Science, Gustavus Adolphus College, St. Peter, (MN). Thesis: “NATO Enlargement in Eastern Europe–Political and Strategic Consequences”. Count Folke Bernadotte Memorial Scholarship recipient. Academic Adviser: Prof. Richard Leitch. 1997-98 AY: Academic exchange year at the University of Aberdeen. Departments of Political Science and Economics. Aberdeen, Scotland, United Kingdom. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 8/20020 – date: Assistant Professor (tenure-track), Department of Slavic and Eurasian Studies, 1 COLA, The University of Texas at Austin. -

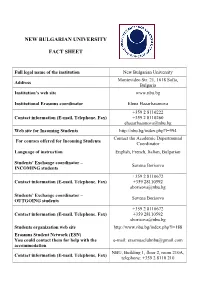

New Bulgarian University Fact Sheet

NEW BULGARIAN UNIVERSITY FACT SHEET Full legal name of the institution New Bulgarian University Montevideo Str. 21, 1618 Sofia, Address Bulgaria Institution’s web site www.nbu.bg Institutional Erasmus coordinator Elena Hazarbasanova +359 2 8110222 Contact information (E-mail, Telephone, Fax) +359 2 8110260 [email protected] Web site for Incoming Students http://nbu.bg/index.php?l=994 Contact the Academic Departmental For courses offered for Incoming Students Coordinator Language of instruction English, French, Italian, Bulgarian Students’ Exchange coordinator – Savena Borisova INCOMING students +359 2 8110672 Contact information (E-mail, Telephone, Fax) +359 28110592 [email protected] Students’ Exchange coordinator – Savena Borisova OUTGOING students +359 2 8110672 Contact information (E-mail, Telephone, Fax) +359 28110592 [email protected] Students organization web site http://www.nbu.bg/index.php?l=188 Erasmus Student Network (ESN) You could contact them for help with the e-mail: [email protected] accommodation NBU, Building 1, floor 2, room 210A, Contact information (E-mail, Telephone, Fax) telephone: +359 2 8110 210 Please find here the list of some organizations (the university has no agreement with them) that the students can contact directly. 1. Imoti BG, website: Housing (private rooms) www.imotibg.com, tel.: + 359 088309151. Contact information (E-mail, Telephone) 2. EPPI, e-mail: [email protected], tel.: + 359 087255979. 3. Art Hostel in the city centre of Sofia, close to the National Palace of Culture www.art-hostel.com Semester dates: 1st October – 17th February Winter semester (including exam session) 23rd February – 10th July Spring semester (including exam session) Application deadlines: Winter semester 1st June Spring semester 1st December Yes, we offer two courses during the academic year: Are there any Bulgarian language courses Winter semester - It is 30 h. -

New Bulgarian University

NEW BULGARIAN UNIVERSITY National Endowment Fund “13 Centuries of Bulgaria” HISTORY POPULATED WITH PEOPLE Bulgarian Society in the Second Half of the 20th Century Interviews Sofia, 2005 1 HISTORY POPULATED WITH PEOPLE Below I will give reasons for the title of this book, which might sound frivolous for a serious documentary work. All the more that it is the first publication from the ramified project “Bulgarian Society in the Second Half of the 20th Century”, which was intended as research but was also conceived as an educational endeavor. It was included in the History programmes at New Bulgarian University and funded by the National Endowment Fund “13 Centuries of Bulgaria” and more specifically by its research funds. An important part of the work is the tracking down, collecting and digitalizing of the significant volume of documents on the above period not only in the Central State Archives, but also in local archives. Part of that documentation has already been made accessible on NBU’s website – a total of 2100 pages. Work on its completion is still under way, being carried out by young historians from the “History of Social Changes” Programme at the Department. In the fall, at a conference in Sozopol, 40 BA, MA and PhD students discussed and shared their experience, the results and the prospects of their indisputably necessary endeavor. And the completion of our task has as its objective to define research for the second half of the last century. It is clear in advance that our project cannot bear fruit quickly, due to the relatively late appearance of young researchers of our most recent history. -

NEW BULGARIAN UNIVERSITY in July 1989 Some University

NEW BULGARIAN UNIVERSITY In July 1989 some university teachers and research- workers established the Society for New Bulgarian University. The aim of the Society was to work for reforms in the Bulgarian university. On 18th September 1991 the Society obtained university status from the Great National Assembly under the name of the New Bulgarian University(SG, ? 80/1991). The first period of NBU development - 1991-1993 was related to the establishment of the institutional framework of the university and to its identification in the public domain. On 17th October 1991 the General meeting of the Society formed, out of its members, the Interim Board of Trustees of NBU. Prof. Bogdan Bogdanov was elected Chair and provisionally exercising the functions of the Rector. The Interim Board of Trustees developed the general directions for development of the university and specified its program for action; established the university structures, approved their compositions and internal regulations. In 1991/1992 were established two main units, functioning as schools: the Free School and Correspondent School (Radio-university). They provided courses, qualification programs and distance learning. At the Free School were established the departments – the research structures of the university. During this period, the educational programs were experimental by nature and with professional orientation, but still then was introduced the credit system, which encouraged student mobility and initiated the inclusion of NBU into the national, and later on into the international, academic community. The courses had an unlimited freedom of topics and involving of lecturers, of content and forms of teaching, of ways of attracting the students. -

SHORT REVIEW by Professor Dr. Petya Lyubomirova Kabakchieva

SHORT REVIEW By Professor Dr. Petya Lyubomirova Kabakchieva, Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, Department of Sociology, PF 3.1. Sociology, anthropology and culture sciences On the monograph with author Rumen Petrov Confused in Pain. Social trauma and social responsibility. Sofia: Paradox, 2018, for participation in a competition for the academic position Associate professor in the professional field 3.4.Social activities, announced by the New Bulgarian University in Sofia, Bulgaria in SG № 97/13.11.2020, with a candidate Chief assistant professor Dr. Rumen Goranov Petrov. I. Assessment of compliance with the minimum national requirements and requirements of the New Bulgarian University As evidenced by the self-assessment presented by the candidate Dr. Rumen Petrov – Appendix No 2, it fully meets the minimum national requirements and the requirements of the NBU. There is no plagiarism in the presented monograph. II. Research (creative) activities and results 1. Assessment of the monograph work, creative performances or other publications, corresponding in volume and integrity of monographic work, including an assessment of the scientific and applied contributions of the author The monograph of Rumen Petrov Confused in Pain. Social trauma and social responsibility is a challenge to a series of adopted norms and views in the Social sciences. It is a challenge to one of the established, albeit controversial, norms – for the value neutrality of the researcher, to which the criticized by him authors such as Ernest Gelner and Benedict Anderson strictly adhere. The author insists that social science is not possible without moral judgment, the scholar must be a morally responsible citizen. Secondly, this value pathos leads to the specific genre and stylistics of the monograph, which, to put it softly, will strongly disturb the accustomed to the strict genre rules scientist, as it, with ease, brings together authors from different scholarly and artistic fields – for example, Nikola Vaptsarov as a researcher of social trauma and J. -

The Master's Program American and British Studies

American and British Studies. Comparative Approaches The Master’s Program American and British Studies. Comparative Approaches at New Bulgarian University is taught entirely in English. It offers courses on American and British literature, philosophy, history, anthropology, cultural studies, history of architecture, film studies, environmental studies. All the courses hold a comparative American-British perspective, thus provoking and stimulating a process of creative and enriching critical thinking. The Program’s hallmark is the Training Conference: organized in the end of each semester and open to wide public, these academic conferences discuss various topics related to the program courses; the presenters are the students and the session chairs – the professors. The Program aims at academic professionalism which can easily unfold on the PhD level later. Reviewed highly and enthusiastically by three US distinguished scholars in the field 15 years ago when it was initially offered, the Program has had students from Bulgaria, Greece, Indonesia, Iraq, Italy, Poland, Syria, Turkey, the Netherlands, Uzbekistan, and the United States. Specialty and Professional Qualification: Cultural Studies: Master’s Degree in American and British Studies Program Completion: Defense of Master’s Thesis International Mobility: Erasmus Agreement with the University of Macerata, Italy Competences: The Program’s graduates are highly qualified in American and British Studies: *they have expertise in American and British history, cultural sociology, philosophy, literature and art history – on a comparative basis; *their critical thinking is well equipped and enables them to effectively do research and further on their scholarly advancement. Professional Fulfillment: The Program’s graduates can pursue an academic career on the PhD level, or have professional realization as teachers, journalists, translators, editors, as well as in the sphere of international relations. -

American and British Studies. Comparative Approaches Master’S Program in English

American and British Studies. Comparative Approaches Master’s Program in English The reward of a thing well done is to have done it. Ralph Waldo Emerson The Master’s Program American and British Studies. Comparative Approaches at New Bulgarian University is taught entirely in English, offering courses on American and British literature, philosophy, history, anthropology, cultural studies, history of music, history of architecture, film studies, semiotics, environmental studies. All the courses hold a comparative American-British perspective, thus provoking and stimulating a creative and rewarding critical thinking. Specialty and Professional Qualification: Cultural Studies: Master’s Degree in American and British Studies Program Completion: Defense of Master’s Thesis International Mobility: Erasmus Agreement with the University of Macerata, Italy Competences: The Program’s graduates are highly qualified in American and British Studies: *they have expertise in American and British history, cultural sociology, philosophy, literature and art – on a comparative basis; *their critical thinking is well equipped and developed and enables them to effectively do research and further on their scholarly growth. Professional Fulfillment: The Program’s graduates can pursue an academic career on the PhD level, or have professional realization as teachers, journalists, translators, editors, also in the sphere of international relationships. American and British Studies. Comparative Approaches Master’s Program in English виList подадат of Courses ръка -

MA PROGRAMME “TRANSLATION and INTERPRETING” the MA

MA PROGRAMME “TRANSLATION AND INTERPRETING” The MA programme “Translation and Interpreting” aims to prepare highly qualified specialists in the sphere of intercultural communication: translators and interpreters with two foreign languages, who can easily adapt to the requirements of the labour market. The students in the programme acquire knowledge in the area of translation studies, translation as an intercultural activity, terminology, contrastive analysis of texts and master practical skills for dealing with translation and translation-related problems. Successful graduates of the programme can do genre-specific translations and consecutive and simultaneous interpreting primarily from language B to language A, but are also trained in reverse translation and translation from language C to language A. The practical courses and self-study projects develop multicomponential translation competences across various text genres: scientific and technical texts, financial and commercial documents, legal, political and economic texts, with special emphasis on using and compiling terminological data banks in the truly computer-assisted environment of New Bulgarian University. The state-of-the art infrastructure at NBU allows for the implementation of innovative methodologies, such as incorporating asynchronous ICT into courses, or blended learning, lecture recording technologies which encourage independent and informal learning paving the way to student autonomy and life-long learning. The training in the programme is conducted within three regular semesters and a final semester for completing a research project thesis; students from disciplines other than philology are required to complete an additional preparatory semester in language studies. The practical experience and internships in translation agencies, business and media companies, municipal and state administration offices facilitate students’ fast adjustment to market needs and enhance their social mobility and their life-long learning skills. -

BA in TOURISM (Taught in Bulgarian)

BA IN TOURISM (taught in Bulgarian) Brief overview of the program: Tuition in the first two years of the program covers general education, instruction in the main academic areas of the major in two-semester courses such as Statistics, Fundamentals of Law, General Sociology, Political Sciences, State and Public Governance, Introduction to Social Psychology, and practical courses such as Microeconomics, Macroeconomics, International Economics, Economic History, Fundamentals of Marketing, etc. Throughout the third and fourth year, training is organized in specialized courses in the program, as well as out-of-class modes of instruction. In the fourth year of studies, the program offers two concentrations leading to a professional qualification: - Tourism Management - Cultural Tourism Management Major and professional qualification: Specialization: Cultural Tourism Major: Cultural Tourism Qualification: Cultural Tourism Manager Specialization: Tourism Management Major: Tourism Management Qualification: Tourism Manager Practical Training: The practical training consists of internships in companies involved in the hotel and catering business, as well as travel agencies. The program provides opportunities for international student mobility in co-operation with universities in Italy, Germany, France, Switzerland, Russia, Portugal and Finland. Competences of program graduates: Program graduates have: - gained knowledge of the economic principles and laws, as well as the characteristics and consistent patterns of development in the tourism industry; - acquired the skills required to organize and manage a tourist company in the sphere of the hotel and catering industry and mediation services. Graduation: To successfully complete the bachelor’s degree program, students have to accumulate the required number of credits and then sit a state examination. Apart from the professional qualification awarded by the program, students could also acquire additional qualifications by enrolling in a minor program.