Cultural Differences in a Globalizing World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greece, Bulgaria and Albania1 General Introduct

Translating Socio-Cultural Anthropology into Education Educational Anthropology and Anthropology of education in SE European countries: Greece, Bulgaria and Albania1 Ioannis Manos, Gerorgia Sarikoudi University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, Greece General Introduction Education System I. Greece The education system in Greece is under the central responsibility and supervision of the state administration, and more specifically, the Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs (MERRA). It consists of three levels: primary, secondary (divided in lower and upper-secondary), and tertiary (higher) education. 1. Overview of the Greek education system According to the Greek constitution, the Greek state is bound to provide all Greek citizens with access to free education at all levels of the state education system. The Greek education system2 consists of three levels: primary, secondary (divided in lower and upper-secondary), and higher (tertiary) education. a) Primary Education3 Primary education includes the pre-primary (kindergarten/‘παιδικός σταθμός’/paidikos stathmos) and the primary schools (‘δημοτικό’/dimotiko). Pre-primary education is compulsory4 and 1 DISCLAIMER: The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. 2 For a summary of the Greek education system, see, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national- policies/eurydice/content/greece_en 3 A non-compulsory early childhood education is provided to children from the age of 2 months to 4-years-old by municipal public institutions (Infant Centers, Infant/Child Centers and Child Centers) or private, pre-school education and care centers. -

Perspectives01 08-Obalka:Perspectives-Obalka 12.6.2008 3:09 Page 1

perspectives01_08-obalka:perspectives-obalka 12.6.2008 3:09 Page 1 Vol. 16, No. 1 2008 PerspeReviewctives of International Affairs Visualising the EU in EU Enlargement Boundaries of Balkanism in EU Accession Discourses Toward a Conception of Welcoming and Cooperating Patriotisms Global Governance vs. State Failure ctives Geopolitical Narratives on Belarus in Contemporary Russia e Persp perspectives01_08-obalka:perspectives-obalka 12.6.2008 3:09 Page 2 BOOKS: Author’s name as it appears on the title page, date of publication in parentheses, title in Italics with ! capitals in principal words, place of publication, publisher: Liefferink, Duncan and Mikael Skou Andersen (eds) (1997) The Innovation of EU Environmental Pol- Perspectives icy. Copenhagen: Scandinavian University Press. Review of International Affairs ARTICLES, CHAPTERS FROM BOOKS AND INTERNET SOURCES: Author’s name, title of article or chapter within single inverted commas with principal words capitalised, ! name(s) of editors(s) if in a book, title of journal or book in italics, volume number, issue number in parentheses, page reference, place of publication and publisher if in a book, url if an internet source: Lisowski, Michael (2002) ‘Playing the Two-Level Game: US President Bush’s Decision to Repudiate the Kyoto Protocol’, Environmental Politics 11 (4): 101–119. CALL FOR PAPERS/NOTES FOR CONTRIBUTORS Aguilar Fernández, Susana (1977) ‘Abandoning a Laggard Role? New Strategies in Spanish Environ- mental Policy’, in D. Liefferink and M. S. Andersen (eds) The Innovation of EU Environmental Policy, pp. Perspectives is a refereed journal published twice a year by the Institute of International Relations, Prague, 156–172. Copenhagen: Scandinavian University Press. -

A Comparative Study of Post-Ottoman Political Influences on Bulgarian National Identity Construction and Conflict

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF POST-OTTOMAN POLITICAL INFLUENCES ON BULGARIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY CONSTRUCTION AND CONFLICT BY Copyright 2008 SPENCER S. STITH Submitted to the graduate degree program in International Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master‘s of Arts ______________________________ Elif Andac, PhD – Sociology, Chairperson ______________________________ Ebenezer Obadare, PhD -Sociology Committee Member ______________________________ Robert F. Baumann, PhD – History Committee Member Date Defended: 15 May 2008 The Thesis Committee for Spencer S. Stith certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF POST-OTTOMAN POLITICAL INFLUENCES ON BULGARIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY CONSTRUCTION AND CONFLICT Committee: ___________________________ Elif Andac, Chairperson* ___________________________ Ebenezer Obadare ___________________________ Robert F. Baumann Date Approved: 08 June 2008 ii Abstract Bulgarian society has a successful history of maintaining a relatively peaceful multicultural environment over centuries. This thesis is a comparative analysis of three transitional periods in Bulgaria coinciding with 1) the latter years of Ottoman dominion: 1762-1877, 2) the end of the Balkan Wars and World Wars I and II: 1878- 1947, and 3) the latter years of the Communist dominion: 1947-1989. These periods will be analyzed with the aim to understand the role that regional political agendas have played in shaping an imagined Bulgarian national identity. It will be shown that when it has occurred, identity-based conflict in Bulgaria can be better explained by examining the contributions of nationalist political influences from 1876 – 1989 on identity construction rather than an inherent Balkan propensity to religious and ethnic intolerance. -

We Want Europe in Nagorno-Karabakh

WE WANT EUROPE IN NAGORNO-KARABAKH This appeal was endorsed by the following public figures from across Europe: Frank Engel, Member of the European Parliament (Luxembourg) - Michèle Rivasi, Member of the European Parliament (France) - Aloys Kabanda, Author, survivor of the genocide of the Tutsi, Ibuka (Belgium) - Bart Staes, Member of the European Parliament (Belgium) - Jill Evans, Member of the European Parliament (United Kingdom) - Peter Niedermüller, Member of the European Parliament (Germany) - Benjamin Abtan, President of the European Grassroots Antiracist Movement - EGAM, Coordinator of the Elie Wiesel Network of Parliamentarians of Europe for the Prevention of Mass Atrocities and Genocides and against Genocide Denial (France) - Josep Maria Terricabras, Member of the European Parliament – (Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya) - Bernard Coulie, Professor and former Dean, the Catholic University of Louvain (Belgium) - Daniyel Demir, President of BDVAD, umbrella organization for Arameans in Germany - Dr Mark Levene, Reader in History at the University of Southampton (United Kingdom) - Dr Ruth Barnett, psychiatrist and writer (United Kingdom) - Dr. Tessa Hofmann, author and chairwoman of the human rights NGO Working Group "Recognition Against Genocide" (Germany) - Francisco Palacios Romeo, Professor of Constitutional Law, Faculty of Law, University of Zaragoza (Spain)- Frank de Boer, Federal Union of European Nationalities (FUEN) (Belgium) - Fredrik Malm, Member of Swedish Parliament, Federal Chairman of the Liberal Party of Sweden, Deputy -

Bulgarian Cultural Identity, Balkanism and Self-Colonisation in Bulgarian Tv Series Staklen Dom (2010-2012)

BULGARIAN CULTURAL IDENTITY, BALKANISM AND SELF-COLONISATION IN BULGARIAN TV SERIES STAKLEN DOM (2010-2012) Daria Pritup Master’s Thesis University of Helsinki Department of World Cultures Area and Cultural Studies April 2017 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Maailman kulttuurien laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Daria Pritup Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Bulgarian Cultural Identity, Balkanism and Self-colonisation in Bulgarian TV Series Staklen dom (2010-2012) Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Alue- ja kulttuurintutkimus / Intercultural Encounters -maisteriohjelma Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu year 71 Huhtikuu 2017 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract (voiko tän kirjoittaa minä muodossa, kts alla ehdotukset) Tutkimuksessa käsittelen suosittua bulgarialaista televisiosarjaa hyödyntäen balkanismin ja itsekolonisaation teorioita löytääkseni merkkejä 2010-luvun bulgarialaisen kulttuuri-identiteetin rakentumisesta. Näiden teorioiden mukaan “Balkan” on käsitteellistetty sivistymättömänä ja jälkeenjääneenä kulttuurillisena alueena, josta “sivistyneen Euroopan” ongelmat juontavat. Länsieurooppalainen kulttuurihegemonia määrittelee aina itsensä “sivistyksen” ja “edistyksen” keskiöön, ja siitä poikkeavat periferiaan. Periferiakulttuurit puolestaan muodostavat kulttuuri-identiteetin, joka perustuu vieraisiin arvoihin ja on aina puutteellinen ja kehittymätön suhteessa keskukseen. Itsekolonisoivat kulttuurit -

Kiril Avramov

Kiril Avramov Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies The University of Texas at Austin 2505 University Avenue, BUR 578 Austin, TX 78712 Phone: (512)-475-6145 [email protected] EDUCATION 2003-2008: Ph.D., Political Science (Република България Министерски съвет, ВАК, образователна и научна степен „Доктор“), University of Sofia, Bulgaria Degree: Ph.D. 4/08 Dissertation: Success Strategies of the Bulgarian Economic Elite 1990-2001. Supervisor: Prof. Alexander Tomov (Deputy PM of Bulgaria 1990-1991). (Public defense on 04/09/2008, unanimous pass, cum laude) – (Образователна и научна степен „Доктор “по научната специалност 05.11.02 „Политология “; тема: „Стратегии за успех на българския икономически елит (1990-2001) “Научна комисия 12, Протокол № 10 от 06.10.2008 г.) 2005- 2006: Central European University (CEU), Budapest, Hungary. Doctoral Support Program (DSP) at the Department of Political Science. (Full tuition scholarship from the University). Academic adviser: Prof. Nenad Dimitrijevic. 2001- 2002: M.A., Diplomacy & International Relations. Department of Political Science, New Bulgarian University, Sofia, Bulgaria. Thesis: “The Epidemic Infectious Disease as an Element of the Stability of the International Security” Academic adviser: Dr. Ivan Nachev. (Cum laude). 1995- 1999: B.A., Political Science, Gustavus Adolphus College, St. Peter, (MN), USA Department of Political Science, Gustavus Adolphus College, St. Peter, (MN). Thesis: “NATO Enlargement in Eastern Europe–Political and Strategic Consequences”. Count Folke Bernadotte Memorial Scholarship recipient. Academic Adviser: Prof. Richard Leitch. 1997-98 AY: Academic exchange year at the University of Aberdeen. Departments of Political Science and Economics. Aberdeen, Scotland, United Kingdom. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 8/20020 – date: Assistant Professor (tenure-track), Department of Slavic and Eurasian Studies, 1 COLA, The University of Texas at Austin. -

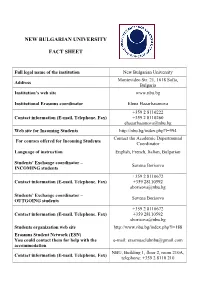

New Bulgarian University Fact Sheet

NEW BULGARIAN UNIVERSITY FACT SHEET Full legal name of the institution New Bulgarian University Montevideo Str. 21, 1618 Sofia, Address Bulgaria Institution’s web site www.nbu.bg Institutional Erasmus coordinator Elena Hazarbasanova +359 2 8110222 Contact information (E-mail, Telephone, Fax) +359 2 8110260 [email protected] Web site for Incoming Students http://nbu.bg/index.php?l=994 Contact the Academic Departmental For courses offered for Incoming Students Coordinator Language of instruction English, French, Italian, Bulgarian Students’ Exchange coordinator – Savena Borisova INCOMING students +359 2 8110672 Contact information (E-mail, Telephone, Fax) +359 28110592 [email protected] Students’ Exchange coordinator – Savena Borisova OUTGOING students +359 2 8110672 Contact information (E-mail, Telephone, Fax) +359 28110592 [email protected] Students organization web site http://www.nbu.bg/index.php?l=188 Erasmus Student Network (ESN) You could contact them for help with the e-mail: [email protected] accommodation NBU, Building 1, floor 2, room 210A, Contact information (E-mail, Telephone, Fax) telephone: +359 2 8110 210 Please find here the list of some organizations (the university has no agreement with them) that the students can contact directly. 1. Imoti BG, website: Housing (private rooms) www.imotibg.com, tel.: + 359 088309151. Contact information (E-mail, Telephone) 2. EPPI, e-mail: [email protected], tel.: + 359 087255979. 3. Art Hostel in the city centre of Sofia, close to the National Palace of Culture www.art-hostel.com Semester dates: 1st October – 17th February Winter semester (including exam session) 23rd February – 10th July Spring semester (including exam session) Application deadlines: Winter semester 1st June Spring semester 1st December Yes, we offer two courses during the academic year: Are there any Bulgarian language courses Winter semester - It is 30 h. -

The Unique Cultural & Innnovative Twelfty 1820

Chekhov reading The Seagull to the Moscow Art Theatre Group, Stanislavski, Olga Knipper THE UNIQUE CULTURAL & INNNOVATIVE TWELFTY 1820-1939, by JACQUES CORY 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. of Page INSPIRATION 5 INTRODUCTION 6 THE METHODOLOGY OF THE BOOK 8 CULTURE IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES IN THE “CENTURY”/TWELFTY 1820-1939 14 LITERATURE 16 NOBEL PRIZES IN LITERATURE 16 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN 1820-1939, WITH COMMENTS AND LISTS OF BOOKS 37 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN TWELFTY 1820-1939 39 THE 3 MOST SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN 39 THE 3 MORE SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – SPANISH, RUSSIAN, ITALIAN 46 THE 10 SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – PORTUGUESE, BRAZILIAN, DUTCH, CZECH, GREEK, POLISH, SWEDISH, NORWEGIAN, DANISH, FINNISH 50 12 OTHER EUROPEAN LITERATURES – ROMANIAN, TURKISH, HUNGARIAN, SERBIAN, CROATIAN, UKRAINIAN (20 EACH), AND IRISH GAELIC, BULGARIAN, ALBANIAN, ARMENIAN, GEORGIAN, LITHUANIAN (10 EACH) 56 TOTAL OF NOS. OF AUTHORS IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES BY CLUSTERS 59 JEWISH LANGUAGES LITERATURES 60 LITERATURES IN NON-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES 74 CORY'S LIST OF THE BEST BOOKS IN LITERATURE IN 1860-1899 78 3 SURVEY ON THE MOST/MORE/SIGNIFICANT LITERATURE/ART/MUSIC IN THE ROMANTICISM/REALISM/MODERNISM ERAS 113 ROMANTICISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 113 Analysis of the Results of the Romantic Era 125 REALISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 128 Analysis of the Results of the Realism/Naturalism Era 150 MODERNISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 153 Analysis of the Results of the Modernism Era 168 Analysis of the Results of the Total Period of 1820-1939 -

56. 'Other' Anthropologies

56. ‘Other’ anthropologies Convenors: Aleksandar Boskovic, Rhodes University [email protected] Thomas Hylland Eriksen, University of Oslo [email protected] Discussant: Mariza G. S. Peirano, University of Brasília [email protected] The main purpose of this workshop is to explore one of the main themes of the conference, namely, the metaphors of ethnographic practice. They are going to be explored in specific contexts of various national/regional anthropological traditions – both in Europe and in a wider context (Americas, Africa, Asia), but excluding the ‘great’ traditions (Anglo-American, French and German). The questions to be discussed include: how have these metaphors changed in a changing world? What do traditions such as (for example) Scandinavian, Polish, Yugoslav, Kenyan and Argentinian have in common, and how do they differ? How have discourses of post- colonialism, post-Marxism and post-structuralism influenced these traditions and what relation did they have with the more dominant (‘central’) anthropological traditions? Finally, what is the future of anthropology in these countries, sometimes referred to as ‘peripheral’? The idea of anthropology that we wish to explore with other participants in this workshop is an idea of a horizontally-structured discipline (or a conglomerate of scholarly disciplines), coping with the challenges of multiculturalism, globalization and transnationalism. These challenges bring closer different anthropological traditions, but they also invoke the necessity for dialogue and co-operation. We believe that bringing together scholars from different traditions and different backgrounds can provide a fruitful basis for discussion, as well as for comparisons of the changing metaphors of ethnographic practice, both within the discipline of anthropology, and within the broader field of social sciences and humanities in general. -

New Bulgarian University

NEW BULGARIAN UNIVERSITY National Endowment Fund “13 Centuries of Bulgaria” HISTORY POPULATED WITH PEOPLE Bulgarian Society in the Second Half of the 20th Century Interviews Sofia, 2005 1 HISTORY POPULATED WITH PEOPLE Below I will give reasons for the title of this book, which might sound frivolous for a serious documentary work. All the more that it is the first publication from the ramified project “Bulgarian Society in the Second Half of the 20th Century”, which was intended as research but was also conceived as an educational endeavor. It was included in the History programmes at New Bulgarian University and funded by the National Endowment Fund “13 Centuries of Bulgaria” and more specifically by its research funds. An important part of the work is the tracking down, collecting and digitalizing of the significant volume of documents on the above period not only in the Central State Archives, but also in local archives. Part of that documentation has already been made accessible on NBU’s website – a total of 2100 pages. Work on its completion is still under way, being carried out by young historians from the “History of Social Changes” Programme at the Department. In the fall, at a conference in Sozopol, 40 BA, MA and PhD students discussed and shared their experience, the results and the prospects of their indisputably necessary endeavor. And the completion of our task has as its objective to define research for the second half of the last century. It is clear in advance that our project cannot bear fruit quickly, due to the relatively late appearance of young researchers of our most recent history. -

Balkan Variations of Orientalism and Occidentalism Nikolay Aretov

316.723(497) Nikolay Aretov University in Sofia, Bulgaria Balkan variations of Orientalism and Occidentalism Abstract: Summarizing, the aim of this paper was to provoke scrutinizing in a Balkan context the notions of Orientalism and Occidentalism – two forms of demonizing the Other, coined in the age of Enlightenment, two phenomena that are ambivalent and imported from other cultures. They interact in a curious manner and took critical place in the mythologues of all the nations in the region although in different ways. Keywords: orientalism, occidentalism, Balkan, Other, demonizing the Other, mental map The idea of the Other is crucial part of the own thought based upon an ontological and epistemologi- identity. People imagine the Other in different ways, cal distinction made between “the Orient” and (most very often he/she is presented as a dangerous En- of the time) “the Occident”. Thus a very large mass emy, like a screen on which we project our own fears of writers, among whom are poets, novelists, philoso- and other emotions on it. Mythical thinking, which is phers, political theorists, economists and imperial alive even nowadays, uses different tools to name administrators, have accepted the basic distinction and imagine the Other and to master it. between East and West as the starting point for elab- The well-known book of Edward Said introduced in orate theories, epics, novels, social descriptions, and international humanity studies the term Orientalism, political accounts, concerning the Orient, its people, with which he designated „a way of coming to terms customs, “mind”, destiny, and so on. This Orientalism with the Orient that is based on the Orient’s place in can accommodate Aeschylus, say, and Victor Hugo, European Western experience”, one specific “style of Dante and Karl Marx.”(Said, 1978,1, 2-3) 89 Nikolay Aretov This was written an the beginning of the work, most famous among authors dealing with this term which finished with a warring: recently. -

NEW BULGARIAN UNIVERSITY in July 1989 Some University

NEW BULGARIAN UNIVERSITY In July 1989 some university teachers and research- workers established the Society for New Bulgarian University. The aim of the Society was to work for reforms in the Bulgarian university. On 18th September 1991 the Society obtained university status from the Great National Assembly under the name of the New Bulgarian University(SG, ? 80/1991). The first period of NBU development - 1991-1993 was related to the establishment of the institutional framework of the university and to its identification in the public domain. On 17th October 1991 the General meeting of the Society formed, out of its members, the Interim Board of Trustees of NBU. Prof. Bogdan Bogdanov was elected Chair and provisionally exercising the functions of the Rector. The Interim Board of Trustees developed the general directions for development of the university and specified its program for action; established the university structures, approved their compositions and internal regulations. In 1991/1992 were established two main units, functioning as schools: the Free School and Correspondent School (Radio-university). They provided courses, qualification programs and distance learning. At the Free School were established the departments – the research structures of the university. During this period, the educational programs were experimental by nature and with professional orientation, but still then was introduced the credit system, which encouraged student mobility and initiated the inclusion of NBU into the national, and later on into the international, academic community. The courses had an unlimited freedom of topics and involving of lecturers, of content and forms of teaching, of ways of attracting the students.