Chapter 9 Water Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hiwassee Geographic Area Updated: June 1, 2017

Hiwassee Geographic Area June 1, 2017 **Disclaimer: The specific descriptions, goals, desired conditions, and objectives only apply to the National Forest System Lands within the Hiwassee Geographic Area. However, nearby communities and surrounding lands are considered and used as context. Hiwassee Geographic Area Updated: June 1, 2017 Description of area The Hiwassee Geographic Area is defined by large rivers running through broad flat valleys and two large lakes surrounded by mountains that provide distinct visitor experiences. The broad river valleys lie at lower elevations than other geographic areas in North Carolina’s National Forests. The steep mountains of this area support short leaf pine, mixed hardwood forests, and large pockets of eastern hemlock. Passing through a gentler mountain landscape, the major rivers of the region include the Hiwassee, Valley, and Nottley Rivers which flow into the Chatuge, Hiwassee, and Apalachia lakes. These rivers and the lakes created by Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) dams provide reactional opportunities for fishing, boating, and other water sports. The lakes of this geographic area form a chain that is home to a diverse number of plant, animal, and warm water fish species that are native to riparian floodplain ecosystems. Prior to European and Anglo-American settlement along with westward expansion, the Hiwassee geographic area was home to the Cherokee and Creek tribes. This area contains several landscape features that figure most prominently in Tribal history and have significant meaning to Tribal identities and beliefs. These locations are important traditional and ceremonial areas for the Cherokee. Communities within this geographic area include Murphy, Hayesville, Warne, Peachtree, Brasstown, Hiwassee Dam, Ranger and the smaller incorporated areas of Unaka and Violet. -

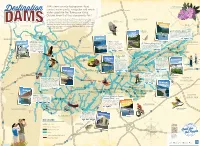

TVA's Dams Provide Hydropower, Flood Control, Water Quality, Navigation

TVA’s dams provide hydropower, ood Catawba Rhododendron (Rhododendron catawbiense) control, water quality, navigation and ample Lexington Destination water supply for the Tennessee Valley. Did you know that they also provide fun? Come summer, TVA operates its dams to ll the reservoirs for recreation. Boating, shing, swimming, rafting and blueway paddling are all supported Bald Eagle KENTUCKY by TVA with boat ramps, swim beaches and put ins. There are plenty of hiking (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and biking trails, picnic pavilions, playgrounds, campsites, scenic overlooks SOUTH and other day-use areas, too. So plan a TVA vacation this year—you’re sure HO W.V. ILLINOIS LSTON 77 to have a dam good time. o R i v i e Rainbow Trout South Holston Dam - 1951 h r (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Because of its depth and clarity, South Holston Lake is a O FORT premier destination for inland scuba diving. The aerating Paducah PATRICK weir below the dam has many benets—among them NRY creating an oxygen-rich environment that’s fostered a HE world-class trout shery. ORRIS 75 MISSOURI N Hopkinsville 65 Kentucky – 1944 24 Norris - 1936 CKY Norris Dam—the rst built by a newly VIRGINIA KENTU Around Kentucky Lake there are Ft. Patrick Henry - 1953 55 formed TVA—is known for its many Fort Patrick Henry Dam is an ideal shing over 12,000 acres of state wildlife hiking and biking trails. The Norris River management areas, that offer small destination. The reservoir is stocked with rainbow Bluff Trail is a must-see destination for trout each year, and is also good for hooking and large game and waterfowl wildower enthusiasts each spring. -

Drought-Related Impacts on Municipal and Major Self- Supplied Industrial Water Withdrawals in Tennessee--Part B

WATER-RESOURCES INITESTIGATIONS REPORT 84-40`'4 DROUGHT-RELATED IMPACTS ON MUNICIPAL AND MAJOR SELF- SUPPLIED INDUSTRIAL WATER WITHDRAWALS IN TENNESSEE--PART B Prepared by U . S . GEOLOGICAL SURVEY in cooperation with TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENT, Division of Water Management TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY, Office of Natural Resources and Economic Development, Division of Air and Water Resources, Regional ����� Table 20 .--Selt-supplied commercial and industrial water user's, Obiorr-Forked Deer River basin [*System received all water from primary surface-water or ground-water source) Water source Average Average County, industry Tributary Number and Source water consumptive Additional information name (SIC code), and basin of intake location capacity use water use (principal products, existing location by city No . employees (river mile) _ (MMgal/d) (Mgal/d) (Mgal /d) problems, and so forth) Car ro11 *Norandal USA, 39A 200 Wells (2) 1 .017 -- Category 7 . Product ° Aluminum sheet foil . Inc . (3353) ; Huntingdon WD .004 Storage capacity equals 300,000 gallons Huntingdon '200,000 gallons for fire protection) . Crockett *Winter Garden, 40C 800 Wells (7) 4 .400 0 .121 Category 7 . Product - Frozen vegetables . Inc . (2037) ; Storage equals 1,500 galions . Bells Drier *Dyersburg Fabrics, 40D 1,200 Wells (2.) .976 .024 Category 7 . Product - Pile fabrics, infant Inc . (2254, 2257, Dyersburg WD .376 fabrics, and glove cloth . Storage capacity 2259) ; Dyersburg equals 550,000 gallons . (,0 Gibson 41 *Beare Company 40B 7 Wells (2) .200 - Category 7 . Service - Refrigerated ware (4222) ; house . Humboldt *Martin Marietta 40B 1,400 Wells (9) .990 .007 Category 7 . Service - Load, assemble, and Sales, Inc . -

Federal Register/Vol. 82, No. 143/Thursday, July 27, 2017/Notices

34976 Federal Register / Vol. 82, No. 143 / Thursday, July 27, 2017 / Notices Description of Respondents: Park Frequency of Collection: One-time. Visitors; Members of the general public. Respondent’s Obligation: Voluntary. Completion Annual Number of time per Annual burden Activity number of responses response * hours * respondents each * (minute) Initial Contact ................................................................................................... 130,000 1 1 2,167 Completed VSC ............................................................................................... 65,000 1 3 3,250 Non-response Survey ...................................................................................... 6,500 1 1 108 Total .......................................................................................................... ........................ ........................ ........................ 5,525 * Rounded. Estimated Annual Non-hour Burden research in System (54 U.S.C. 100701); Before including your address, phone Cost: None. National Park Service Protection number, email address, or other Research Mandate (54 U.S.C. 100702); personal identifying information in your III. Comments National Environmental Policy Act of as comment, you should be aware that On January 10, 2017, we published a amended in 1982 (Sec 102 [42 U.S.C. your entire comment—including your Federal Register notice (82 FR 3024) 4332A]). personal identifying information—may announcing that we would submit this be made publicly available at any time. Tim -

The Tennessee Valley Authority During World War II

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2005 A River for War, a Watershed to Change: The Tennessee Valley Authority During World War II William Wade Drumright University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Drumright, William Wade, "A River for War, a Watershed to Change: The Tennessee Valley Authority During World War II. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2005. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4321 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by William Wade Drumright entitled "A River for War, a Watershed to Change: The Tennessee Valley Authority During World War II." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. Robert J. Norrell, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: William Bruce Wheeler, Kurt Piehler, Charles S. Aiken Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

TVA PUBLIC LANDS Wear a Helmet—If You Fall In, a Helmet Can Protect Key

BE A GOOD STEWARD PADDLE POINTERS The Hiwassee River is known for its clean water and Follow these 12 tips to help keep your next paddle trip safe: pristine rural shorelines. Here’s how you can play a part in keeping the river beautiful: Know Your Limits—Paddle water that is appropriate to your skills. Not sure about • Stay on the path. Shorelines are fragile ecosystems; where to find it? Talk to a local paddle shop owner about good places to paddle please restrict launching and landing to designated for every skill level. areas only. Keep an Eye on the Weather—Storms can spring up quickly in the south bringing • Leave no trace behind. No littering—whatever you lightning, high winds and choppy water. Point your prow toward shore whenever pack in, you pack out. you hear thunder, no matter how distant. ON THE HIWASSEE RIVER • Look, don’t touch. Do not disturb any natural or cultural resources you may encounter. Follow the Law for recreational vessels of the United States. Whether you are stepping into your • Respect private property. Do not trespass above the high water mark. boat or board for the first time or have • Be a happy camper. Camp only in designated areas. Bring Flotation—Always wear a Coast Guard-approved lifejacket, type logged enough hours on the water to • Don’t play with fire. No campfires unless otherwise designated. two or three at minimum. Children under 12 years of age must rival the guides in the Valley, having wear a lifejacket.* a little back-pocket information is TVA PUBLIC LANDS Wear a Helmet—If you fall in, a helmet can protect key. -

Investigating Instabilities with HEC-RAS Unsteady Flow Modeling for Regulated Rivers at Low Flow Stages

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2014 Investigating Instabilities with HEC-RAS Unsteady Flow Modeling for Regulated Rivers at Low Flow Stages Jennifer Kay Sharkey University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Hydraulic Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Sharkey, Jennifer Kay, "Investigating Instabilities with HEC-RAS Unsteady Flow Modeling for Regulated Rivers at Low Flow Stages. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2014. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3183 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Jennifer Kay Sharkey entitled "Investigating Instabilities with HEC-RAS Unsteady Flow Modeling for Regulated Rivers at Low Flow Stages." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Environmental Engineering. John S. Schwartz, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Jon M. Hathaway, Thanos N. Papanicolaou Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Investigating Instabilities with HEC-RAS Unsteady Flow Modeling for Regulated Rivers at Low Flow Stages A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Jennifer Kay Sharkey December 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Jennifer Sharkey. -

In 1996, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) Completed a Five

OVERVIEW OF RESERVOIR RELEASE IMPROVEMENTS AT 20 TVA DAMS By John M. Higgins,1 Member, ASCE, and W. Gary Brock2 ABSTRACT: In 1987, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) authorized a com- prehensive review of reservoir operating priorities that had been followed since 1933. The purpose was to ensure optimum operation of the reservoir system, rec- ognizing that needs, demands, and values change over time. The review resulted in a ®ve-year, $50 million program to improve the quantity and quality of releases from 20 dams in the Tennessee Valley. TVA worked with state and federal resource agencies to de®ne minimum ¯ow and dissolved oxygen targets for each tailwater. Facilities and operating procedures were designed and installed to meet the target conditions. This paper describes the facilities, operating procedures, and perfor- mance of the reservoir release improvements. Alternative approaches, monitoring requirements, operational problems, and costs are discussed. Results from four years of operation are presented. INTRODUCTION In 1996, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) completed a ®ve-year, $50 million program to improve the quantity and quality of releases from 20 dams in the Tennessee Valley. Prior to the program, over 500 km of tailwaters were being adversely impacted by reservoir releases. Hydropower operations re- sulted in periods of zero ¯ow below some dams. Thermal reservoir strati®- cation resulted in the release of water low in dissolved oxygen (DO), affecting downstream water quality, aquatic habitat, recreation, and waste assimilation. To improve the releases, TVA worked with resource agencies and nongov- ernmental organizations to de®ne minimum ¯ow and dissolved oxygen tar- gets. -

Hiwassee Dam Unit 2 Reversible Pump-Turbine (1956)

TVA Tennessee Valley Authority HIWASSEE DAM UNIT 2 REVERSIBLE PUMP-TURBINE (1956) A National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark July 14, 1981 Murphy, North Carolina ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The East Tennessee Section of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers gratefully acknowledges the efforts of those who helped organize the landmark dedication of the Hiwassee unit 2. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers Dr. Robert Gaither, President Robert Vogler, Vice President, Region IV J. Karl Johnson, immediate past Vice President, Region IV Sylvan J. Cromer, History & Heritage, Region IV Earl Madison, Field Service Director ASME National History & Heritage Committee ASME East Tennessee Section Prof. J. J. Ermenc, Chairman Charles Chandley, Chairman R. Carson Dalzell, Secretary Mancil Milligan, Vice Chairman R. S. Hartenberg Larry Boyd, Treasurer J. Paul Hartman Steve Doak, Secretary R. Vogel, Smithsonian Institution Guy Arnold Allis-Chalmers Corporation Siemens-Allis, Inc. James M. Patterson, Manager, Marketing Services Paul Rieland, Large Rotating Apparatus Division Hydro-Turbine Division Lloyd Zellner, Public Relations NATIONAL HISTORIC MECHANICAL ENGINEERING LANDMARK Hiwassee Unit 2 Reversible Pump-Turbine 1956 This integration of pump and turbine was the first of many to be installed in power plant systems in the United States; it was the largest and most powerful in the world. As a "pump storage" unit in the Tennessee Valley Authority's system it offered significant economies in the generation of electrical energy. The unit was designed by engineers of the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Allis-Chalmers Company. It was built by Allis-Chalmers Company. The Hiwassee unit 2 is the 61st landmark designated by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. -

Flow Duration and Low Flows of Tennessee Streams Through 1992

Flow Duration and Low Flows of Tennessee Streams through 1992 By GEORGE S. OUTLAW and JESS D. WEAVER U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 95-4293 Prepared in cooperation with the TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION and the TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY Nashville, Tennessee 1996 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm name in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information write to: Copies of this report may be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Earth Science Information Center 810 Broadway, Suite 500 Open-File Reports Section Nashville, Tennessee 37203 Box 25286, MS 517 Denver Federal Center Denver, Colorado 80225 CONTENTS Abstract.................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose and scope ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Previous studies.......................................................................................................................................................... -

Drought-Related Impacts on Municipal and Major Self- Supplied Industrial Water Withdrawals in Tennessee--Part B

WATER-RESOURCES INITESTIGATIONS REPORT 84-40`'4 DROUGHT-RELATED IMPACTS ON MUNICIPAL AND MAJOR SELF- SUPPLIED INDUSTRIAL WATER WITHDRAWALS IN TENNESSEE--PART B Prepared by U . S . GEOLOGICAL SURVEY in cooperation with TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENT, Division of Water Management TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY, Office of Natural Resources and Economic Development, Division of Air and Water Resources, Regional ��� the year, average rainfall ranges from 3 .96 to 5 .33 inches with March usually being the wettest month . The surface-water supply for this basin is derived from precipitation and runoff within the area, streamflow including ground water discharge entering the area from adjacent areas, and ground-water discharge to streams within the area . Average discharge data for selected hydrologic data stations are presented in table 39 . Theoretically, there is a large quantity of surface water available for use in this basin . However, because of the small number of available storage sites and the increased evaporative losses of surface water that occur with this development, this quantity is not realistically obtainable . Ground Water West Tennessee embraces two physiographic provinces . One is the West Tennessee Plain, including the subdivision known as the West Tennessee Uplands, and the other is the Mississippi River Valley . The West Tennessee Plain extends from the western margin of the Western Valley of the Tennessee River, or the divide, known as the West Tennessee Uplands, separating eastward flowing drainage to the Tennessee River from streams flowing westward to the Mississippi River . This area contains three major drainage basins : the Obion-Forked Deer, the Hatchie, and the Memphis Area which includes the Loosahatchie River, Wolf River, and Nonconnah Creek . -

Bicycle Route Cue Sheets

Bicycle Routes for Cherokee, Clay, Graham, & Macon Counties Southern Blue Ridge Bike Plan Tatham’s Gap Crossing Gravel Grinder k N k Southern Blue Ridge Bike Routes Remember to obey all traffic signs and signals 13 Miles ut ro e A Tatham’s Gap Crossing ADVANCED Gravel Grinder Total Go Total Go Miles Miles Miles Miles 0.0 0.1 GO! Start Route at the Andrews rest area 6.8 2.5 g Turn RIGHT to stay on National and visitor’s information parking lot. Forest Road. Head east out of the parking area. 9.3 2.5 h Continue onto Long Creek Road. 0.1 0.1 f Turn LEFT onto Locust Street. 11.8 0.6 g Turn RIGHT onto Snowbird Road. 0.2 0.3 h After crossing US-19/129/74, contin- ue onto Beaver Creek Road. 12.4 0.3 h Continue onto Atoah Street. 0.5 1.0 g Turn RIGHT onto Stewart Road. 12.7 0.1 Turn RIGHT to stay on Atoah g Street. 1.5 0.4 f Turn LEFT onto Tatham Gap Road (Britain Creek Road). 12.8 0.2 Turn LEFT onto Circle Street, then f keep LEFT on Circle Street. 1.9 1.0 g Turn RIGHT onto National Forest Road / Tatham Gap Road. 13.0 0.1 Turn LEFT onto Moose Branch f Road. 2.9 3.2 k Keep RIGHT to stay on National For- est Road / Tatham Gap Road. 13.1 0.1 g Turn RIGHT onto Knight Street. 6.1 0.7 Turn LEFT onto National Forest Road, 13.2 0.0 END The route ends here! You are at f then keep LEFT to stay on National the Graham County Public Library.