THE ATROPHY OR MARASMUS of INFANTS Being Thesis Presented

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

341 Nutrient Deficiency Or Disease Definition/Cut-Off Value

10/2019 341 Nutrient Deficiency or Disease Definition/Cut-off Value Any currently treated or untreated nutrient deficiency or disease. These include, but are not limited to, Protein Energy Malnutrition, Scurvy, Rickets, Beriberi, Hypocalcemia, Osteomalacia, Vitamin K Deficiency, Pellagra, Xerophthalmia, and Iron Deficiency. Presence of condition diagnosed, documented, or reported by a physician or someone working under a physician’s orders, or as self-reported by applicant/participant/caregiver. See Clarification for more information about self-reporting a diagnosis. Participant Category and Priority Level Category Priority Pregnant Women 1 Breastfeeding Women 1 Non-Breastfeeding Women 6 Infants 1 Children 3 Justification Nutrient deficiencies or diseases can be the result of poor nutritional intake, chronic health conditions, acute health conditions, medications, altered nutrient metabolism, or a combination of these factors, and can impact the levels of both macronutrients and micronutrients in the body. They can lead to alterations in energy metabolism, immune function, cognitive function, bone formation, and/or muscle function, as well as growth and development if the deficiency is present during fetal development and early childhood. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that less than 10% of the United States population has nutrient deficiencies; however, nutrient deficiencies vary by age, gender, and/or race and ethnicity (1). For certain segments of the population, nutrient deficiencies may be as high as one third of the population (1). Intake patterns of individuals can lead to nutrient inadequacy or nutrient deficiencies among the general population. Intakes of nutrients that are routinely below the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) can lead to a decrease in how much of the nutrient is stored in the body and how much is available for biological functions. -

Severe Malnutrition: a Global Approach. INSTITUTION International Children's Centre, Paris (France)

, DOCUMENT RESUME ED 371 865 PS 022 466 AUTHOR Pelletier, Jean-Gerard TITLE Severe Malnutrition: A Global Approach. INSTITUTION International Children's Centre, Paris (France). REPORT NO ISSN-0379-2269 PUB DATE 93 NOTE 88p. AVAILABLE FROMChildren in the Tropics, International Children's Centre, Chateau de Longchamp, Bois de Boulogne, 75016, Paris, France ($10; annual subscription: $40 for 6 issues). PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Children in the Tropics; n208-209 1993 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biological Influences; *Child Health; Children; Cultural Influences; Developing Nations; Disease Incidence; *Diseases; Foreign Countries; Global - Approach; *Hunger; *Intervention; Medical Services; *Nutrition; Nutrition Instruction; Poverty; Program Evaluation; Rehabilitation; Socioeconomic Influences IDENTIFIERS Anthropometry; KwashisKor; Marasmus; Psychological Influences ABSTRACT This report examines the immediate and underlying causes of malnutrition in the developing world. The first section discusses the effects of malnutrition on childhood development and examines the efficacy of nutritional rehabilitation. The second section addresses the medical effects of severe malnutrition, including the onset of ponderostatural (weight) retardation, behavioral disorders, dehydration, anemia, hypothermia, hypoglycemia. and diarrhea. The third section focuses on anthropometric approaches to treating malnourished children, which treat children on an individual basis based upon their particular condition. The fourth section examines the biological effects of severe malnutrition, discussing deficiencies in serum proteins, electrolytes, trace elements, and hormonal levels, along with their immunological consequences. The fifth section explains the nutritional approach to the problem, looking at protein, vitamin, and mineral deficiencies lnd specific rehabilitation procedures and foods. The sixth section focuses on a cultural approach to malnutrition, discussing dietary and social customs that affect nutrition and eating behaviors. -

Marasmus- 1985

Postgraduate Medical Journal (1985) 61, 915-923 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.61.720.915 on 1 October 1985. Downloaded from Marasmus- 1985 D. Barltrop and B.K. Sandhu Department ofChild Health, Charing Cross and Westminster Medical School, London, UK. Introduction Dr Wilfred J. Pearson writing for the first volume of In 1959 Jelliffe coined the term protein-calorie this Journal in 1925 defined marasmus (Greek: maras- malnutrition (PCM) of early childhood to include mos, wasting) as 'a chronic state of malnutrition of a mild, moderate and various types of severe degrees of severe grade' but pointed out that 'we must retain the malnutrition. The advent of the International System conception ofcases varying in severity from those who of Units (SI) resulted in the introduction of the term simply show an insufficient gain or stationary weight protein energy malnutrition (PEM). The World with few systemic changes, to the most extreme form Health Organisation (WHO, 1973) defined PEM as which is merely the end result of repeated nutritional follows: 'A range of pathological conditions arising or constitutional disturbances.' He described oedema from coincidental lack, in varying proportions, of in some cases as a complication of marasmus. The protein and calories, occurring most frequently in clinical picture of the syndrome, later described as infants and young children and commonly associated kwashiorkor, was not generally recognized at this with infection'. This is not dissimilar from Wilfred time, although a number of authors had described it Pearson's view of marasmus. (Czerney & Keller, 1928). In order to treat and, more importantly, to prevent a In 1933 Cicely D. -

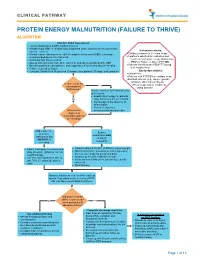

Protein Energy Malnutrition (Failure to Thrive) Algorithm

CLINICAL PATHWAY PROTEIN ENERGY MALNUTRITION (FAILURE TO THRIVE) ALGORITHM Conduct Initial Assessment • History and physical (H&P), nutrition focused • Weight height, BMI, % of ideal body weight and exam: assess severity (symmetric edema = severe) Inclusion criteria: • • Consider basic labs based on H&P; A complete blood count (CBC) is strongly Children newborn to 21 years of age • recommended due to risk of anemia Inpatients admitted for evaluation and • Additional labs based on H&P treatment of Protein Energy Malnutrition • Assess micronutrients: iron, zinc, vitamin D, and others as indicated by H&P (PEM) or Failure to thrive (FTT) OR • • Baseline potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium if concerned about re-feeding Patients identified with PEM/FTT during • Calorie count up to 3 days their hospital stay. • Consults: Social Work, Registered Dietician, Occupational Therapy, and Lactation Exclusion criteria: • Outpatients • Patients with FTT/PEM secondary to an identified concern (e.g., cancer, genetic condition, other chronic illness). Is there a risk for •Pts w/ suspected or confirmed micronutrient Yes eating disorder deficiencies? Initiate treatment for micronutrients deficiencies: • Empiric zinc therapy for patients No older than 6 months for 1 month • Iron therapy in the absence of inflammation • Vitamin D and other What are the micronutrients based on labs degrees of malnutrition and risk of refeeding? Mild, moderate, Severe or severe malnutrition AND malnutrition but at risk of NO RISK of refeeding refeeding • • Initiate feeding per recommended Initiate feeding at 30-50% of RDA for current weight • daily allowance (RDA) for current Monitor potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium weight and age once to twice a day for a total of 4 days • • Use PO route if patient is able to Advance by 10-20% if labs are normal • take 70% of estimated calories If labs abnormal hold off on advancing feed until orally corrected • Start thiamine Advance calories to meet level for catch up growth. -

Nutritional Dermatoses in the Hospitalized Patient

HOSPITAL CONSULT IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE SOCIETY FOR DERMATOLOGY HOSPITALISTS Nutritional Dermatoses in the Hospitalized Patient Melissa Hoffman, MS; Robert G. Micheletti, MD; Bridget E. Shields, MD Nutritional deficiencies may arise from inadequate nutrient intake, abnormal nutrient absorption, or improper nutrient PRACTICE POINTS utilization.4 Unfortunately, no standardized algorithm for • Nutritional deficiencies are common in hospitalized screening and diagnosing patients with malnutrition exists, patients and often go unrecognized. making early physical examination findings of utmost • Awareness of the risk factors predisposing patients importance. Herein, we present a review of acquired nutri- to nutritional deficiencies and the cutaneous manifes- tional deficiency dermatoses in the inpatient setting. tations associated with undernutrition can promote copy early diagnosis. Protein-Energy Malnutrition • When investigating cutaneous findings, undernutri- tion should be considered in patients with chronic Protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) refers to a set of infections, malabsorptive states, psychiatric illness, related disorders that include marasmus, kwashiorkor and strict dietary practices, as well as in those using (KW), and marasmic KW. These conditions frequently are certain medications. seen in developing countries but also have been reported 5 • Prompt nutritional supplementation can prevent patient in developed nations. Marasmus occurs from a chronic morbidity and mortality and reverse skin disease. deficiencynot of protein and calories. Decreased insulin pro- duction and unopposed catabolism result in sarcopenia and loss of bone and subcutaneous fat.6 Affected patients include children who are less than 60% ideal body weight Cutaneous disease may be the first manifestation of an underlying nutri- 7 tional deficiency, highlighting the importance of early recognition by der- (IBW) without edema or hypoproteinemia. -

INCIDENCE of UTRITIONAL DEFICIENCY DISEASES AMONG the BANTU and COLOURED Populanons in SOUTH AFRICA AS REFLECTED by the RESULTS of a QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEY*

504 S.A. MEDICAL JOUR AL 18 June 1966 N22 (Supplemenr-SlJIl1h African Jo//mal of Nurririun) INCIDENCE OF UTRITIONAL DEFICIENCY DISEASES AMONG THE BANTU AND COLOURED POPULAnONS IN SOUTH AFRICA AS REFLECTED BY THE RESULTS OF A QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEY* J. F. POTGIETER,** S. A. FELLINGHAM.t AND M. L. ESER** Although it is today generally conceded by nutritionists (vii) Crireria for rhe clillical diagllosis of the specific IIl11ri that malnutrition is a major problem in the Republic and rional diseases, and assumes serious proportions in the younger non-White (viii). Descripriolls of 1I01l-specific sigm alld symprol1ls. In formatIon under (vii) and (viii) was provided in order t age-groups, no reliable information is at present available facilitate the diagnosis of the various diseases and the recoo which gives a true picture of the extent of the problem nition of signs and symptoms referred to in the questionnair~. throughout the country. This information was considered necessary as, without it, the cnteria adopted by different practitioners and their evaluatior To obtain detailed and accurate information on the of the severity of the diseases might vary considerably. prevalence of nutritional disease in all areas of the coun In an accompanying letter, the doctors were asked to keer try, it would be necessary to conduct field surveys on records for a 4-week period during May/June and anotheI samples from all sections of the population-a large and during NovemberfDecember 1960. An additional copy of the unwieldy task. As it was thought that medical practitioners questionnaire was included for use during the latter period. -

Pediatric Malnutrition: Under- and Over-Weight in Children

Pediatric Malnutrition: Under- and Over-weight in Children Daniel Jackson, MD University of Utah School of Medicine 2012 Undernutrition: Global and Local Famine •Political Instability •Distribution of Resources •Social Chaos •Survival/Recovery Nutrient Deficiency Maternal-Child Dyad •Maternal Nutrition/Health •Intrauterine Onset •Nursing insufficiency •Weaning/transition Malabsorption •Environmental Factors •Infection: parasitosis •MalabsorptionÆreduced intake •InflammationÆincreased energy needs Kwashiorkor Displaced from nursing Low protein alternatives Endemic Infection GI protein loss HypoalbuminemiaÆEdema Marasmus Protein-Calorie Undernutrition Fat and Muscle depletion Preserved plasma proteins Preserved homeostasis Failure to Thrive: Our world Genetics Prenatal environment Behavioral factors Psychosocial context Disease factors To Thrive HomeostasisHomeostasis FullFull physiologicphysiologic functionfunction WeightWeight gaingain LinearLinear growthgrowth CranialCranial growthgrowth NeurodevelopmentNeurodevelopment SocialSocial integrationintegration Navigating The Growth Curve ExpectationsExpectations DeviationsDeviations RecoveryRecovery FalteringFaltering AcuteAcute wastingwasting ChronicChronic stuntingstunting CranialCranial stasisstasis CDC Growth Curves: 0-36 months CDC Growth Curves: 2-20 years Body Mass Index: kg/m2 Body Mass Index [BMI]: 2 years to 20 years BMI = weight (kg) / height2 (m2) Extremely Obese: BMI >99th %ile 95 Obese: BMI 95th to <99th %ile 90 85 Overweight: BMI 85th to <95th %ile 75 50 25 10 -

Risk Factors for Early Childhood Malnutrition in Uganda

Risk Factors for Early Childhood Malnutrition in Uganda Joyce K. Kikafunda, PhD*; Ann F. Walker, PhD‡; David Collett, PhD§; and James K. Tumwine, MBChBi ABSTRACT. Objective. To assess the dietary and en- Conclusions. This first account of dietary and envi- vironmental factors influencing stunting and other signs ronmental risk factors involved in the etiology of early of poor nutritional status of children <30 months of age childhood malnutrition in Uganda indicates differences in a central Ugandan community, whose main dietary in risk factors for marasmus and underweight compared staples are banana (matoki) and maize. with stunting and low MUAC. The high prevalence of Methods. The study was a cross-sectional survey us- malnutrition and current infection of children in this ing stratified multistage random sampling to select survey suggests poor immune function as a result of households with a child <30 months of age in rural and inadequate nutrition. Pediatrics 1998;102(4). URL: http:// semi-urban environments. A questionnaire was admin- www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/102/4/e45; infection, istered to mothers of 261 infants and toddlers in their malnutrition, risk factors, stunting, survey, Uganda. home setting. Their health status was assessed by clinical examination and anthropometric measurements (mid- upper arm circumference [MUAC], weight, and supine ABBREVIATIONS. MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference; PEM, protein-energy malnutrition; SD, standard deviation. length). Results. A large minority (21.5%) of the children sur- veyed were found in poor health after clinical examina- utrition and health reports in Uganda have tion: 3.8% being classified as suffering from kwashiorkor indicated that although the country is well and 5.7% with marasmus. -

Serum and Red Cell Folates, and Serum Vitamin B12 in Protein Calorie Malnutrition

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.48.5.366 on 1 May 1973. Downloaded from Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1973, 48, 366. Serum and red cell folates, and serum vitamin B12 in protein calorie malnutrition M. KHALIL, A. TANIOS, M. MOGHAZY, M. K. AREF, S. MAHMOUD, and M. EL LOZY From the Departments of Paediatrics, Clinical Pathology, and Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Alexandria, Alexandria, Egypt Khalil, M., Tanios, A., Moghazy, M., Aref, M. K., Mahmoud, S., and el Lozy, M. (1973). Archives of Disease in Childhood, 48, 366. Serum and red cell folates, and serum vitamin B12 in protein calorie malnutrition. In 22 cases of kwashiorkor, 19 cases of marasmus, and 16 normal controls, red cell folate, serum folate, and serum vitamin B1, were estimated, and the bone marrow and peripheral blood examined. Erythrocyte folate deficiency was shown in 9 cases of kwashiorkor and 7 cases of marasmus. Serum folate deficiency was present in 14 cases of kwashi- orkor and 7 cases of marasmus. Megaloblastosis was found in 45% of cases of kwashiorkor and 37% of cases of marasmus. Megaloblastosis and macrocytosis correlated more with erythrocyte than with serum folate deficiency. Serum vitamin B1, levels in children with kwashiorkor or marasmus did not differ from those of normal controls. The role of folate deficiency in the pathogenesis of megaloblastosis in protein calorie malnutrition was confirmed. copyright. A hypochromic anaemia of iron deficiency is a Material and methods salient finding in patients with protein calorie The study was carried out on 22 infants (12 males and malnutrition (Khalil, Awwad, and Hafez, 1968). -

Malnutrition in Asia and Neurological Consequences

Ann Natl Acad Med Sci (India), 47(1&2): 1-12, 2011 Malnutrition in Asia and Neurological Consequences Jagjit S. Chopra*, Sudesh S. Prabhakar* and Pratibha D. Singhi** Departments of Neurology* and Peadiatric Medicine**, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh-160012 ABSTRACT Prevalence of malnutrition is a global phenomenon but the greatest contribution towards it is from the developing countries. Malnutrition impairs physical growth, cognitive functions of brain, physiological functions, immune response changes. Twenty Seven percent of children under 5 years are malnourished in the developing countries. India contributes to approximately 5.6 million child deaths annually with almost one billion children dying worldwide from the consequences of malnutrition. Malnutrition produces lasting effect on developing brain during the “Brain growth spurt’’ phase which corresponds to the period from 30 weeks of gestation to two-year of post natal age. In the peripheral nervous system the growth of axons, migration of Schwann cells and onset of myelination starts at 14 to 20 weeks of gestation. Malnutrition causes muscle wasting, hypotonia and impaired deep tendon reflexes from 30-40% of malnourished children. Deficiency of micronutrients in malnourished can cause myelopathy, peripheral neuropathy, dementia, infantile seizures, infantile tremor syndrome, night blindness, optic neuropathy and spinocerebellar degeneration. Keywords : Malnutrition, prevalence, central nervous system, peripheral nervous system. Correspondence : Dr Jagjit S. Chopra, H.No. 1153, Sector 33-C, Chandigarh- 160020 Malnutrition in Asia and Neurological Consequences 2 Introduction According to WHO by 2015 According to United Nations malnutrition will decrease by 17.6%. statistics about 25% of Indian population Globally 113.4 million children younger particularly children <14 years are then 5 yrs are affected. -

Scurvy in a Patient with AIDS: Case Report

Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 44(1):122-123, jan-fev, 2011 Case Report/Relato de Caso Scurvy in a patient with AIDS: case report Escorbuto em paciente com AIDS: Relato de caso André Luiz Maltos1, Luciana Ligia da Silva1, Aderbal Garcia Bernardes Junior1, Guilherme Vannucchi Portari1 and Daniel Ferreira da Cunha1 ABSTRACT CASE REPORT We report the case of a 35-year-old homeless alcoholic and illicit drug user, with AIDS, who was admitted to the emergency unit complaining of asthenia and a weight loss of 30kg over the preceding three months. Clinical and laboratory A 35-year-old homeless HIV-infected man who was an alcoholic data confirmed a diagnosis of marasmus, bacterial pneumonia, chorioretinitis and illicit drug user was admitted to the emergency room complaining caused by Toxoplasma gondii and oral Candida infection. The patient also of asthenia, night sweating, a dry cough and a weight loss of 30kg presented loss of tongue papillae, gingival hypertrophy, perifollicular over the preceding three months. Over this period, his energy intake hyperkeratosis and hemorrhage, coiled, corkscrew-like hair, anemia, hypoalbuminemia, increased C-reactive protein levels and low serum vitamin had derived mainly from cachaça, a strong (40%) alcoholic beverage C levels. The patient developed severe gastric hemorrhage, with hemodynamic made from sugar cane. During the clinical examination, the patient instability and terminal disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. showed obvious signs of dehydration and muscle and fat wasting, Keywords: AIDS. Scurvy. Malnutrition. with a productive cough and chest pain upon inhalation. Despite having no fever (37°C), he had tachypnea and tachycardia and RESUMO presented rales in the left lung. -

Nutritional Pathology Topics Nutritional Deficiencies

9/7/2012 Nutritional Pathology Topics • Nutritional deficiencies – Protein – Energy Malnutrition – Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia – Vitamin Deficiencies – Mineral Deficiencies • Obesity นายแพทย ดร.ณตพล ศุภณัฐเศรษฐกุล • Diet and Systemic Diseases ภาควิชาพยาธิวิทยา คณะแพทยศาสตร มหาวิทยาลัยนเรศวร 12 กันยายน พ.ศ. 2555 Nutritional deficiencies An aequate diet should provide: 1. Energy, in the form of carbohydrates, fats, proteins 2. Essential (as well as nonessential) amino acids and fatty acids as building blocks 3. Vitamins and minerals function as coenzymes and hormones in vital metabolic pathways http://www.easy-weightloss-tips.com/images/diabetic-food-pyramid.jpg 1 9/7/2012 ภาวะทุพโภชนาการ (Malnutrition) Common Causes Primary malnutrition : missing from the diet • Poverty (homeless, aged, children) • Ignorance Secondary malnutrition : adequate nutrients (infants, adolescents, pregnant women) supply, but malnutrition may result from - Malabsorption • Chronic alcoholism - Impaired nutrient use or storage • Acute and chronic illnesses - Excess nutrient losses (trauma, burn, cancer, etc.) - Increased need for nutrients • Self-imposed dietary restriction (GI diseases, chronic wasting diseases, acute critical illness) Protein - Energy malnutrition (PEM) - PEM refers to a range of clinical syndrome characterized by an inadequate dietary intake of protein and calories to meet the body’s needs. - Primary (children) and Secondary (illness) PEM - Two polar forms: - Marasmus, - Kwashiorkor A B 2 9/7/2012 1. Marasmus. - Severe reduction in caloric intake