Assessment and Applications of the Conversion of Chemical Energy to Mechanical Energy Using Model Rocket Engines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

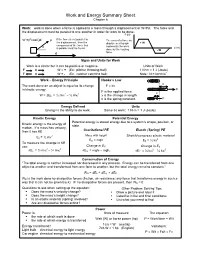

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

The Mechanical Equivalent of Heat

THE MECHANICAL EQUIVALENT OF HEAT INTRODUCTION This is the classic experiment, first performed in 1847 by James Joule, which led to our modern view that mechanical work and heat are but different aspects of the same quantity: energy. The classic experiment related the two concepts and provided a connection between the Joule, defined in terms of mechanical variables (work, kinetic energy, potential energy. etc.) and the calorie, defined as the amount of heat that raises the temperature of 1 gram of water by 1 degree Celsius. Contemporary SI units do not distinguish between heat energy and mechanical energy, so that heat is also measured in Joules. In this experiment, work is done by rubbing two metal cones, which raises the temperature of a known amount of water (along with the cones, stirrer, thermometer, etc,). The ratio of the mechanical work done (W) to the heat which has passed to the water plus parts (Q), determines the constant J (J = W/Q). THE EXPERIMENT CAUTION: The apparatus must not be operated without oil between the cones. The cones have to be cleaned and a tiny drop of oil put between the rubbing surfaces (caution! too much oil will reduce the friction excessively and make the experiment impossible). The apparatus is shown in Figure 1. The heat generated in the system is absorbed by different parts: the water, the inner and outer cones, the stirrer and the immersed part of the temperature probe. The total increase in heat, including all these contributions, is therefore: Q = (MCw + M′Cbr + v Cth) ∆T = constant1 × ∆T (1) -1 -1 Cw = specific heat of water = 1.00 cal g C (by definition of the calorie) -1 ° -1 Cbr = specific heat of brass (cones and stirrer) = 0.089 cal g C -3 ° -1 Cth = heat capacity per unit volume of temperature probe = 0.013 cal cm C M = mass of water (in g) M′ = mass of cones and stirrer (in g) v = volume of the immersed part of the temperature probe (in cm3). -

Fuel Wise Or Fuelish? Grades 9 to 12

LESSON PLAN Fuel Wise or Fuelish? Grades 9 to 12 SUMMARY LESSON OBJECTIVES In this lesson, the students will explore the different impacts Upon completing this lesson the students will: using alternative fuels has on the economy. • Learn how world events affect supply and demand for The students will research and compare different cars. petroleum; They will determine the cost of operation for one year to • Explore why it is important for South Carolinians to use include price, fuel, insurance, property taxes, title, tag, and alternative fuels; and maintenance, as well as determine the most cost-effective choice of vehicle, based on their research. • Make decisions pertinent to choosing a fuel-efficient car. ESSENTIAL QUESTION How have alternative fuels impacted the economy? DURATION The activity requires about one to two weeks to complete. 2014 S.C. SCIENCE STANDARDS CORRELATIONS Standard H.P.3: The student will demonstrate an understanding of how the interactions among objects can be explained and predicted using the concept of the conservation of energy. CONCEPTUAL UNDERSTANDING H.P.3A.: Work and energy are equivalent to each other. Work is defined as the product of displacement and the force causing that displacement; this results in the transfer of mechanical energy. Therefore, in the case of mechanical energy, energy is seen as the ability to do work. This is called the work-energy principle. The rate at which work is done (or energy is transformed) is called power. For machines that do useful work for humans, the ratio of useful power output is the efficiency of the machine. -

Mechanical Energy

Chapter 2 Mechanical Energy Mechanics is the branch of physics that deals with the motion of objects and the forces that affect that motion. Mechanical energy is similarly any form of energy that’s directly associated with motion or with a force. Kinetic energy is one form of mechanical energy. In this course we’ll also deal with two other types of mechanical energy: gravitational energy,associated with the force of gravity,and elastic energy, associated with the force exerted by a spring or some other object that is stretched or compressed. In this chapter I’ll introduce the formulas for all three types of mechanical energy,starting with gravitational energy. Gravitational Energy An object’s gravitational energy depends on how high it is,and also on its weight. Specifically,the gravitational energy is the product of weight times height: Gravitational energy = (weight) × (height). (2.1) For example,if you lift a brick two feet off the ground,you’ve given it twice as much gravitational energy as if you lift it only one foot,because of the greater height. On the other hand,a brick has more gravitational energy than a marble lifted to the same height,because of the brick’s greater weight. Weight,in the scientific sense of the word,is a measure of the force that gravity exerts on an object,pulling it downward. Equivalently,the weight of an object is the amount of force that you must exert to hold the object up,balancing the downward force of gravity. Weight is not the same thing as mass,which is a measure of the amount of “stuff” in an object. -

A Review on Thermoelectric Generators: Progress and Applications

energies Review A Review on Thermoelectric Generators: Progress and Applications Mohamed Amine Zoui 1,2 , Saïd Bentouba 2 , John G. Stocholm 3 and Mahmoud Bourouis 4,* 1 Laboratory of Energy, Environment and Information Systems (LEESI), University of Adrar, Adrar 01000, Algeria; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Sustainable Development and Computing (LDDI), University of Adrar, Adrar 01000, Algeria; [email protected] 3 Marvel Thermoelectrics, 11 rue Joachim du Bellay, 78540 Vernouillet, Île de France, France; [email protected] 4 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Av. Països Catalans No. 26, 43007 Tarragona, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 13 July 2020 Abstract: A thermoelectric effect is a physical phenomenon consisting of the direct conversion of heat into electrical energy (Seebeck effect) or inversely from electrical current into heat (Peltier effect) without moving mechanical parts. The low efficiency of thermoelectric devices has limited their applications to certain areas, such as refrigeration, heat recovery, power generation and renewable energy. However, for specific applications like space probes, laboratory equipment and medical applications, where cost and efficiency are not as important as availability, reliability and predictability, thermoelectricity offers noteworthy potential. The challenge of making thermoelectricity a future leader in waste heat recovery and renewable energy is intensified by the integration of nanotechnology. In this review, state-of-the-art thermoelectric generators, applications and recent progress are reported. Fundamental knowledge of the thermoelectric effect, basic laws, and parameters affecting the efficiency of conventional and new thermoelectric materials are discussed. The applications of thermoelectricity are grouped into three main domains. -

Mechanical Energy Kinetic Energy 1 2 Ek = 2 Mv Where Ek Is Energy (Kg-M2/S2) V Is Velocity (M/S) Gravitational Potential Energy

Mechanical Energy Kinetic Energy 1 2 Ek = 2 mv where Ek is energy (kg-m2/s2) v is velocity (m/s) Gravitational Potential Energy Eg = W = mgz where w is work (kg-m2/s2) m is mass (kg) z is elevation above datum Pressure of surrounding fluid (potential energy per unit volume) Total Energy (per unit volume) 1 2 Etv = 2 r v + r gz + P Total Energy (per unit mass) or Bernoulli equation 1 P 2 Etm = 2 v + gz + r For a incompressible, frictionless fluid v2 P 2g + z + r g = constant This is the total mechanical energy per unit weight or hydraulic head (m) Groundwater velocity is very low, m/yr, so kinetic energy can be dropped 2 P h = z + r g Head in water of variable density hf = (r p/r f)hp where hp = pressure head hf = freshwater head Force Potential P F = gh = gz + r Darcy's Law dh KA dF Q = -KA dl = - g dl Applicability of Darcy's Law (Laminar Flow) r vd R = m < 1 where v = discharge velocity (m/s) d = diameter of passageway (m) R = Reynold's number Specific Discharge (Darcy Flux) and Average Linear Velocity Q dh v = A = -K dl Q K dh v = = - x neA ne dl 3 Equations of Ground-Water Flow Confined Aquifers Flux of water in and out of a Control Volume ¶ inMx = r wqxdydz; outMx = r wqxdydz + ¶x (r wqx) dx dydz; ¶ netMx = - ¶x (r wqx) dx dydz ¶ netMy = - ¶y (r wqy) dy dxdz ¶ netMz = - ¶z (r wqz) dz dxdy ¶ ¶ ¶ netMflux = - ( ¶x (r wqx) + ¶y (r wqy) + ¶z (r wqz) ) dxdydz From Darcy's Law ¶h ¶h ¶h qx = - K ¶x qy = - K ¶y qz = - K ¶z and assuming that w and K do not vary spatially ¶2h ¶2h ¶2h M = K + + r dxdydz net flux ( ¶x2 ¶y2 ¶z2 ) w Note hydraulic head and hydraulic conductivity are easier to measure than discharge. -

Chapter 07: Kinetic Energy and Work Conservation of Energy Is One of Nature’S Fundamental Laws That Is Not Violated

Chapter 07: Kinetic Energy and Work Conservation of Energy is one of Nature’s fundamental laws that is not violated. Energy can take on different forms in a given system. This chapter we will discuss work and kinetic energy. If we put energy into the system by doing work, this additional energy has to go somewhere. That is, the kinetic energy increases or as in next chapter, the potential energy increases. The opposite is also true when we take energy out of a system. the grand total of all forms of energy in a given system is (and was, and will be) a constant. Exam 2 Review • Chapters 7, 8, 9, 10. • A majority of the Exam (~75%) will be on Chapters 7 and 8 (problems, quizzes, and concepts) • Chapter 9 lectures and problems • Chapter 10 lecture Different forms of energy Kinetic Energy: Potential Energy: linear motion gravitational rotational motion spring compression/tension electrostatic/magnetostatic chemical, nuclear, etc.... Mechanical Energy is the sum of Kinetic energy + Potential energy. (reversible process) Friction will convert mechanical energy to heat. Basically, this (conversion of mechanical energy to heat energy) is a non-reversible process. Chapter 07: Kinetic Energy and Work Kinetic Energy is the energy associated with the motion of an object. m: mass and v: speed SI unit of energy: 1 joule = 1 J = 1 kg.m2/s2 Work Work is energy transferred to or from an object by means of a force acting on the object. Formal definition: *Special* case: Work done by a constant force: W = ( F cos θ) d = F d cos θ Component of F in direction of d Work done on an object moving with constant velocity? constant velocity => acceleration = 0 => force = 0 => work = 0 Consider 1-D motion. -

Chapter 4 EFFICIENCY of ENERGY CONVERSION

Chapter 4 EFFICIENCY OF ENERGY CONVERSION The National Energy Strategy reflects a National commitment to greater efficiency in every element of energy production and use. Greater energy efficiency can reduce energy costs to consumers, enhance environmental quality, maintain and enhance our standard of living, increase our freedom and energy security, and promote a strong economy. (National Energy Strategy, Executive Summary, 1991/1992) Increased energy efficiency has provided the Nation with significant economic, environmental, and security benefits over the past 20 years. To make further progress toward a sustainable energy future, Administration policy encourages investments in energy efficiency and fuel flexibility in key economic sectors. By focusing on market barriers that inhibit economic investments in efficient technologies and practices, these programs help market forces continually improve the efficiency of our homes, our transportation systems, our offices, and our factories. (Sustainable Energy Strategy, 1995) 54 CHAPTER 4 Our principal criterion for the selection of discussion topics in Chapter 3 was to provide the necessary and sufficient thermodynamics background to allow the reader to grasp the concept of energy efficiency. Here we first want to become familiar with energy conversion devices and heat transfer devices. Examples of the former include automobile engines, hair driers, furnaces and nuclear reactors. Examples of the latter include refrigerators, air conditioners and heat pumps. We then use the knowledge gained in Chapter 3 to show that there are natural (thermodynamic) limitations when energy is converted from one form to another. In Parts II and III of the book, we shall then see that additional technical limitations may exist as well. -

Determination of Mechanical Energy Loss in Steady Flow by Means of Dissipation Power

Archives of Hydro-Engineering and Environmental Mechanics Vol. 64 (2017), No. 2, pp. 73–85 DOI: 10.1515/heem-2017-0005 © IBW PAN, ISSN 1231–3726 Determination of Mechanical Energy Loss in Steady Flow by Means of Dissipation Power Wojciech Artichowicz, Jerzy M. Sawicki Gdańsk University of Technology, Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering, ul. G. Narutowicza 11/12, 80-233 Gdańsk, Poland, e-mails: [email protected], [email protected] (Received April 06, 2017, revised October 24, 2017) Abstract When systems of simple geometry like pipes or regular channels are considered, the mechan- ical energy loss of the fluid flow can be expressed by local and longitudinal empirical energy loss coefficients. However, in the case of large spatially distributed objects, there are no simple approaches to this task. In practice, general recommendations addressing different types of objects are used, but they usually provide very coarse estimates of energy loss. In this work, a new methodology for determination of mechanical energy loss in steady flow is proposed. This methodology is based on the observation that the magnitude of the power of energy dissipation in turbulent flow can be determined using the averaged flow velocity and turbulent viscosity coefficient. To highlight this possibility, an analysis of the magnitudes of the power of the main and fluctuating components of turbulent flow is presented. The correctness of the method is verified using an example of laminar and turbulent flows in a circular pipe. The results obtained show clearly that the proposed methodology can be used for mechanical energy loss determination in flow objects. -

A Novel Thermomechanical Energy Conversion Cycle ⇑ Ian M

Applied Energy 126 (2014) 78–89 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Applied Energy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/apenergy A novel thermomechanical energy conversion cycle ⇑ Ian M. McKinley, Felix Y. Lee, Laurent Pilon Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department, Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA highlights Demonstration of a novel cycle converting thermal and mechanical energy directly into electrical energy. The new cycle is adaptable to changing thermal and mechanical conditions. The new cycle can generate electrical power at temperatures below those of other pyroelectric power cycles. The new cycle can generate larger electrical power than traditional mechanical cycles using piezoelectric materials. article info abstract Article history: This paper presents a new power cycle for direct conversion of thermomechanical energy into electrical Received 21 May 2013 energy performed on pyroelectric materials. It consists sequentially of (i) an isothermal electric poling Received in revised form 18 February 2014 process performed under zero stress followed by (ii) a combined uniaxial compressive stress and heating Accepted 26 March 2014 process, (iii) an isothermal electric de-poling process under uniaxial stress, and finally (iv) the removal of compressive stress during a cooling process. The new cycle was demonstrated experimentally on [001]-poled PMN-28PT single crystals. The maximum power and energy densities obtained were Keywords: 41 W/L and 41 J/L/cycle respectively for cold and hot source temperatures of 22 and 130 °C, electric field Pyroelectric materials between 0.2 and 0.95 MV/m, and with uniaxial load of 35.56 MPa at frequency of 1 Hz. -

Direct Thermal Energy Conversion Materials, Devices, and Systems

Quadrennial Technology Review 2015 Chapter 6: Innovating Clean Energy Technologies in Advanced Manufacturing Technology Assessments Additive Manufacturing Advanced Materials Manufacturing Advanced Sensors, Controls, Platforms and Modeling for Manufacturing Combined Heat and Power Systems Composite Materials Critical Materials Direct Thermal Energy Conversion Materials, Devices, and Systems Materials for Harsh Service Conditions Process Heating Process Intensification Roll-to-Roll Processing Sustainable Manufacturing - Flow of Materials through Industry Waste Heat Recovery Systems Wide Bandgap Semiconductors for Power Electronics U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Quadrennial Technology Review 2015 Direct Thermal Energy Conversion Materials, Devices, and Systems Chapter 6: Technology Assessments NOTE: This technology assessment is available as an appendix to the 2015 Quadrennial Technology Review (QTR). Direct Thermal Energy Conversion Materials, Devices, and Systems is one of fourteen manufacturing-focused technology assessments prepared in support of Chapter 6: Innovating Clean Energy Technologies in Advanced Manufacturing. For context within the 2015 QTR, key connections between this technology assessment, other QTR technology chapters, and other Chapter 6 technology assessments are illustrated below. Connec=ons to other QTR Chapters and Technology Assessments Grid Electric Power Buildings Fuels Transporta=on Cri=cal Materials Sustainable Manufacturing / Direct Thermal Energy Conversion Flow of Materials through Industry Materials, Devices and -

Mechanical Energy and Heat

P31220 Lab Mechanical Energy and Heat Purpose: Students will observe the conversion of mechanical energy to thermal energy. Introduction: The principle of conservation of energy is surprisingly new. No one person can take the credit for discovering it. Instead, the discovery of Conservation of Energy was made bit by bit, piece by piece, until the evidence finally became overwhelming sometime in the late 19th century. One of these pieces is the idea that a specific amount of mechanical energy can be converted to a specific amount of thermal energy and back again. We are being very careful about our terminology. “Work” and “heat” represent energy that is in motion. When we do work on a system, we increase its mechanical energy. A pot of hot water has thermal energy. When it cools off, it transfers “heat” to its surroundings. These are subtle distinctions, but important ones. There are many energy units because energy is used to explain such a variety of phenomena. Historically, various units were invented to make it easy to do calculations in various contexts. Electrical engineers use the kilowatt-hr. Chemists like the calorie, which is the amount of energy needed to warm up 1 cm3 of water by 1°C. Food chemists like the kilocalorie, also called the big- C Calorie. The foot-pound, erg, Joule, electron Volt, BTU, and therm are all useful energy units. If you wish to work with energy, get used to unit conversions. In this lab, you will observe and measure the conversion of mechanical energy into thermal energy. You’ll measure the mechanical energy in Joules and the thermal energy in calories.