NTS Insight- Humanitarian Assistance in the Asia-Pacific During COVID-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-2020 Annual Report

Bringing Hope in Emergency Building partnerships for the future Annual Report 2019-2020 The Catholica BRINGING Agency HOPE for IN EMERGENCYInternational Aid and Development “The Spirit of the Lord is Contents upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good Our Vision news to the poor. He has Vision and Mission 1 sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery From the Chair 2 of sight to the blind, to let From the CEO 3 the oppressed go free, to Principles 4 proclaim the year of the Strategy 5 Lord’s favour.” Our Work Luke 4:17-19 Where we work 6-7 Myanmar 8 Australia 9 Lebanon 10 South Sudan 11 Solomon Islands 12 Vietnam 13 Evaluation and learning 14 COVID-19 response 15 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that this publication may contain images or names of people who have since passed away. Caritas Our Year Australia acknowledges the traditional owners and custodians, past and present, of the land on which all our offices are located. Year in review 16-17 Our year in advocacy 18 Cover: Villagers in Afghanistan learn how to protect themselves from COVID-19 In their own words 19 through hand-washing and hygiene measures. Photo: Stefanie Glinski/Catholic Relief Services Financial snapshot 20-21 Inside cover: A child in the Turkana region of Kenya, an arid region and the poorest in Kenya, with 60% of the population living in extreme poverty. Photo: Garry Walsh, Trocaire Fundraising spotlight 22 Design: Three Blocks Left ABN 90 970 605 069 Published November 2020 by Caritas Australia © Copyright Caritas Australia 2020 Leadership ISSN 2201-3083 In keeping with Caritas Australia’s high standard of transparency, this version has Our Diocesan network 23 been updated to correct minor typographical errors from an earlier version. -

Accept Corona As Part of Life, Return to Normalcy

Indian Horizon National English Daily [email protected] www.indianhorizon.org RNI NO: DELENG/2013/51507 In memory of Dr Asima Kemal and Prof. Dr. Salim W Kemal [email protected] Volume Issue No: 139 Published from New Delhi & Hyderabad New Delhi, Thursday, May 21, 2020 No: 7 Pages 12 + 4 pull out (P16) Price: 3.00 INS TO SC: CENTRE, STATES TOOK HCQ AFTER VALET MAIN AIM IS TO WIN AN OLY OWE SEVERAL CRORES’ DUES TESTED COVID POSITIVE, MEDAL OF DIFFERENT COLOUR TO MEDIA INDUSTRY SAYS TRUMP IN TOKYO: MARY P-3 P-8 P-11 HOLIDAY NOTICE New Delhi, May 20 (IANS) mentation of the scheme that Prime Minister Narendra Modi NARENDRA MODI : is expected to bring about Blue THE WORLD UNDER ATTACK on Wednesday said several de- Revolution through sustainable cisions taken by the Cabinet Migrants, fishermen, and responsible development SCOURGE OF CORONAVIRUS today focused on welfare of of fisheries sector in India un- migrants, poor and senior citi- senior citizen to gain from der two components -- Central zens, adding these would facili- Sector Scheme and Centrally TOTAL TALLY IN INDIA Our office will be tate easier availability of credit Cabinet decisions Sponsored Scheme -- at a to- mounts to 1,06,750, death closed on 21st of May, and create opportunities in the tal estimated investment of Rs 2020 on the occasion fisheries sector. equate livelihood for rural-ur- 20,050 crore. toll 3,303 of Shab-E-Qadr. While welcoming the Cabi- ban communities.On ‘Pradhan The scheme is likely to ad- Therefore, net’s decision on formalisation Mantri Matsya Sampada Yo- dress the critical gaps in the of microfood processing enter- jana’, Modi said it will “revolu- fisheries sector and realize its there will be no issue prises, PM Modi tweeted: “The tionise the fisheries sector”. -

Being Prepared for Unprecedented Times Peter Layton

Being prepared for unprecedented times National mobilisation conceptualisations and their implications Peter Layton 1 2 3 BEING PREPARED FOR UNPRECEDENTED TIMES National mobilisation conceptualisations and their implications Peter Layton 3 About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute (GAI) is an internationally recognised research centre in the Griffith Business School. We reflect Griffith University’s longstanding commitment and future aspirations for the study of and engagement with nations of Asia and the Pacific. At GAI, our vision is to be the informed voice leading Australia’s strategic engagement in the Asia Pacific— cultivating the knowledge, capabilities and connections that will inform and enrich Australia’s Asia-Pacific future. We do this by: i) conducting and supporting excellent and relevant research on the politics, security, economies and development of the Asia-Pacific region; ii) facilitating high level dialogues and partnerships for policy impact in the region; iii) leading and informing public debate on Australia’s place in the Asia Pacific; and iv) shaping the next generation of Asia-Pacific leaders through positive learning experiences in the region. Visit us at: www.griffith.edu.au/asiainstitute About the publication This paper has been developed with the support of the Directorate of Mobilisation, Force Design Division within the Australian Department of Defence. Mobilisation involves civil society, emergency services and all levels of government. The sharing of the research undertaken aims to encourage informed community debate. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Australian Government or the Department of Defence, or any part thereof. -

Multiple Disaster and Debt Sustainability in Small Island

December 2020 UNCTAD Research Paper No. 55 UNCTAD/SER.RP/2020/14 Anja Slany Multiple disasters and Associate Expert Division for Africa, Least Developed debt sustainability in Countries, and Special Programmes (ALDC), UNCTAD Small Island Developing [email protected] States Abstract Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are the most disaster-prone countries in the world. With an increasing frequency over time, they are regularly hit by severe storms and other disasters, causing on average an annual damage of 2.1 percent of GDP. In the aftermath of disasters, reconstruction efforts require massive financial resources which are often covered through external borrowing. On top, small countries are highly dependent and exposed to economic shocks what results in a massive drop of GDP and exports during global crisis such as COVID-19. In order to provide policy makers with tools to maintain debt sustainability, a better understanding of the options and the complexity between disaster response and debt is required. This paper estimates the impact of multiple disasters on debt sustainability indicators in SIDS over the period 1980 to 2018. Applying a fixed- effects and a Synthetic Control estimator, the results indicate an only weak correlation between a severe natural disaster and external debt what can be related to the restrictions of already highly indebted SIDS to access adequate financing. The paper discusses the implications for financing stronger resilience to disasters in the future and calls for stronger multilateral cooperation and greater flexibility in the accessibility to pre- and post- disaster financial instruments. Key words: Natural disasters, debt, SIDS, panel data © 2020 United Nations 1 UNCTAD Research Paper No. -

MSA Newsletter 7 | 19 May 2020 1

A newsletter for Member Schools of Marist Schools Australia published fortnightly during term time From Frank Malloy Dear Colleagues, Kindness, it’s contagious! Early in the first month of the current pandemic appearing in this country, Prime Minister Morrison urged Australians to be kind to one another. The statement seemed remarkable from a Prime Minister, and entirely appropriate. As we navigate the impacts of COVID-19, take pride in our collective efficacy in minimising infections through adherence to the various prescribed measures, and make the necessary careful adjustments to new ways of working and living whilst the virus remains active, the need to be kind to one another is growing rather than diminishing. In difficult times great leaders come to the fore, at all levels of society. This has certainly been the case in our Marist schools, among staff, parents and students. The demands upon parents and students these past months have been extraordinary and rightly teachers and Principals across the country are being hailed as unassuming, national heroes. The speed and agility with which our school communities have responded to the crisis and the many changes it has necessitated is remarkable. Most impressive has been the strategic, purposeful evaluation by teachers of the various off-site learning arrangements and the manner in which new insights are influencing learning and teaching as students return to school. Reports of greater engagement particularly by boys in the coeducational settings have been common, whilst students of a quieter disposition have also featured prominently in positive feedback. Most overwhelming from our schools across the country, is the demonstrable sheer delight of our young people to be together again, learning at school. -

SOLAR UNDER STORM for POLICYMAKERS Select Best Practices for Resilient Photovoltaic Systems for Small Island Developing States

M OUN KY T C A I O N R I N E STIT U T SOLAR UNDER STORM FOR POLICYMAKERS Select Best Practices for Resilient Photovoltaic Systems for Small Island Developing States BY CHRISTOPHER BURGESS, JUSTIN LOCKE, LAURIE STONE AUTHORS & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AUTHORS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Christopher Burgess, Justin Locke, Laurie Stone The authors thank the following individuals/ organizations for offering their insights and * Authors listed in alphabetical order perspectives on this work: Joseph Goodman, Rocky Mountain Institute ADDITIONAL CONTRIBUTORS (previously) Sanya Detweiler, Clinton Climate Initiative, Clinton Chris Needham, FCX Solar Foundation Frank Oudheusden, FCX Solar Shifaana Thowfeequ, UN-OHRLLS CONTACTS Christopher Burgess, [email protected] Sanya Detweiler, [email protected] Shifaana Thowfeequ, [email protected] SUGGESTED CITATION Laurie Stone, Christopher Burgess, and Justin Locke, Solar Under Storm for Policymakers: Select Best Practices for Resilient PV Systems for Small Island Developing States, 2020, www.rmi.org/insight/solar- under-storm-for-policymakers. All images from iStock unless otherwise noted. ABOUT US M OUN KY T C A I O N R I N E STIT U T ABOUT ROCKY MOUNTAIN INSTITUTE Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI)—an independent nonprofit founded in 1982—transforms global energy use to create a clean, prosperous, and secure low-carbon future. It engages businesses, communities, institutions, and entrepreneurs to accelerate the adoption of market-based solutions that cost-effectively shift from fossil fuels to efficiency and renewables. RMI has offices in Basalt and Boulder, Colorado; New York City; the San Francisco Bay Area; Washington, D.C.; and Beijing. ABOUT THE CLINTON FOUNDATION Building on a lifetime of public service, President Clinton established the Clinton Foundation on the simple belief that everyone deserves a chance to succeed, everyone has a responsibility to act, and we all do better when we work together. -

Tropical Cyclone Harold & Covid 19

WASH Cluster Lessons Learn 2020 TROPICAL CYCLONE HAROLD & COVID 19 LESSONS LEARNT July 2020. 1 WASH Cluster Lessons Learn 2020 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 Objectives................................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. 3 Results ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Annex 1. List of participants .................................................................................................... 15 Annex 2: Questions for WASH SOP development ................................................................... 16 2 WASH Cluster Lessons Learn 2020 Introduction Vanuatu declared a COVID 19 pandemic and declared a state of emergency for its response in March 2020. WASH responded with hygiene and sanitation promotion measures across all provinces. When COVID 19 promotional measures were progressing well, a category 5 Tropical Cyclone Harold swept through the north central part of Vanuatu causing widespread damage to infrastructures and livelihood on 6-7 April 2020. The most affected islands were Santo (West, South, South East Santo, Malo, Aore, and the offshore islands, Central Pentecost 1, Central -

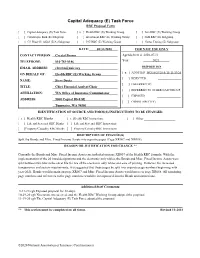

Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force RBC Proposal Form

Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force RBC Proposal Form [ ] Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force [ x ] Health RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Life RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Catastrophe Risk (E) Subgroup [ ] Investment RBC (E) Working Group [ ] SMI RBC (E) Subgroup [ ] C3 Phase II/ AG43 (E/A) Subgroup [ ] P/C RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Stress Testing (E) Subgroup DATE: 08/31/2020 FOR NAIC USE ONLY CONTACT PERSON: Crystal Brown Agenda Item # 2020-07-H TELEPHONE: 816-783-8146 Year 2021 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] DISPOSITION [ x ] ADOPTED WG 10/29/20 & TF 11/19/20 ON BEHALF OF: Health RBC (E) Working Group [ ] REJECTED NAME: Steve Drutz [ ] DEFERRED TO TITLE: Chief Financial Analyst/Chair [ ] REFERRED TO OTHER NAIC GROUP AFFILIATION: WA Office of Insurance Commissioner [ ] EXPOSED ________________ ADDRESS: 5000 Capitol Blvd SE [ ] OTHER (SPECIFY) Tumwater, WA 98501 IDENTIFICATION OF SOURCE AND FORM(S)/INSTRUCTIONS TO BE CHANGED [ x ] Health RBC Blanks [ x ] Health RBC Instructions [ ] Other ___________________ [ ] Life and Fraternal RBC Blanks [ ] Life and Fraternal RBC Instructions [ ] Property/Casualty RBC Blanks [ ] Property/Casualty RBC Instructions DESCRIPTION OF CHANGE(S) Split the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets into separate pages (Page XR007 and XR008). REASON OR JUSTIFICATION FOR CHANGE ** Currently the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets are included on page XR007 of the Health RBC formula. With the implementation of the 20 bond designations and the electronic only tables, the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets were split between two tabs in the excel file for use of the electronic only tables and ease of printing. However, for increased transparency and system requirements, it is suggested that these pages be split into separate page numbers beginning with year-2021. -

COVID-19 FHA Decision Support Tool UPDATED 20 MAY 2020

UNCLASSIFIED CENTER FOR EXCELLENCE IN DISASTER MANAGEMENT & HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE WWW.CFE-DMHA.ORG COVID-19 FHA Decision Support Tool UPDATED 20 MAY 2020 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED List of Countries and U.S. Territories in USINDOPACOM AOR Notes: For quick access to each section place cursor over section and press Ctrl + Click Updated text in last 24 hours highlighted in yellow Table of Contents AMERICAN SAMOA .................................................................................................................................................... 3 AUSTRALIA ................................................................................................................................................................. 5 BANGLADESH ............................................................................................................................................................. 7 BHUTAN ................................................................................................................................................................... 12 BRUNEI ..................................................................................................................................................................... 15 CAMBODIA ............................................................................................................................................................... 17 CHINA ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

A Review of Media Coverage of Climate Change and Global Warming in 2020 Special Issue 2020

A REVIEW OF MEDIA COVERAGE OF CLIMATE CHANGE AND GLOBAL WARMING IN 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE 2020 MeCCO monitors 120 sources (across newspapers, radio and TV) in 54 countries in seven different regions around the world. MeCCO assembles the data by accessing archives through the Lexis Nexis, Proquest and Factiva databases via the University of Colorado libraries. Media and Climate Change Observatory, University of Colorado Boulder http://mecco.colorado.edu Media and Climate Change Observatory, University of Colorado Boulder 1 MeCCO SPECIAL ISSUE 2020 A Review of Media Coverage of Climate Change and Global Warming in 2020 At the global level, 2020 media attention dropped 23% from 2019. Nonetheless, this level of coverage was still up 34% compared to 2018, 41% higher than 2017, 38% higher than 2016 and still 24% up from 2015. In fact, 2020 ranks second in terms of the amount of coverage of climate change or global warming (behind 2019) since our monitoring began 17 years ago in 2004. Canadian print media coverage – The Toronto Star, National Post and Globe and Mail – and United Kingdom (UK) print media coverage – The Daily Mail & Mail on Sunday, The Guardian & Observer, The Sun & Sunday Sun, The Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph, The Daily Mirror & Sunday Mirror, and The Times & Sunday Times – reached all-time highs in 2020. has been As the year 2020 has drawn to a close, new another vocabularies have pervaded the centers of critical year our consciousness: ‘flattening the curve’, in which systemic racism, ‘pods’, hydroxycholoroquine, 2020climate change and global warming fought ‘social distancing’, quarantines, ‘remote for media attention amid competing interests learning’, essential and front-line workers, in other stories, events and issues around the ‘superspreaders’, P.P.E., ‘doomscrolling’, and globe. -

Compound Climate Risks in the COVID-19 Pandemic

comment Compound climate risks in the COVID-19 pandemic The COVID-19 pandemic will be an unprecedented test of governments’ ability to manage compound risks, as climate hazards disrupt outbreak response around the world. Immediate steps can be taken to minimize climate-attributable loss of life, but climate adaptation also needs a long-term strategy for pandemic preparedness. Carly A. Phillips, Astrid Caldas, Rachel Cleetus, Kristina A. Dahl, Juan Declet-Barreto, Rachel Licker, L. Delta Merner, J. Pablo Ortiz-Partida, Alexandra L. Phelan, Erika Spanger-Siegfried, Shuchi Talati, Christopher H. Trisos and Colin J. Carlson he COVID-19 emergency has acutely Floods Heat waves Wildfires overshadowed public reckoning with Tthe climate crisis; the outbreak is still growing in most places, with over three million confirmed cases in 185 countries Wildfires at the time of writing. The pandemic’s disruption of daily lives, health systems Hurricanes Typhoons and economies is unprecedented, and reverberations will continue long after the Locust Heat waves Cyclones first wave of infections ebbs and a vaccine crises is developed. As outbreaks continue, governments will be faced with developing Floods and adjusting policies that address not Droughts and water only the pandemic itself, but also potential scarcity Floods collisions and intersections with other regional or global crises. Bushfires A concerning body of evidence already indicates that climate hazards, which are Fig. 1 | Likely upcoming climate hazards during the COVID-19 pandemic. Climate-attributable risks are increasing in frequency and intensity likely to intersect with the COVID-19 crisis all around the world, with many already causing disruptions under climate change, are likely to intersect or likely to do so over the next 12 to 18 months. -

OUTCOMES Meeting of the CRGA

OUTCOMES Meeting of the CRGA SUBCOMMITTEE ON STRATEGIC PLAN IMPLEMENTATION 28 May 2020 (Noumea, New Caledonia, and by videoconference) ___________________________________________________________________________________ OPENING 1. The CRGA Subcommittee on Strategic Plan Implementation (Subcommittee) met by videoconference on 28 May 2020, linking participants in Canberra, Australia; Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia (FSM); Suva, Fiji; Papeete, French Polynesia; Noumea, New Caledonia; Wellington, New Zealand; Alofi, Niue; Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea; Nuku’alofa, Tonga; Washington D.C., USA. The meeting was chaired by New Caledonia, and was attended by the following member countries and territories: Australia, Cook Islands, FSM, Fiji, France, French Polynesia, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, PNG, Tonga, and United States of America; and also by the European Union and senior executives and staff of the Secretariat, led by the Director-General. Palau, Samoa and the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS) observed the meeting. 2. The main objectives of the meeting were for the Secretariat to provide an update to members and a forum to discuss SPC’s responses to COVID-19 and Tropical Cyclone Harold; to consider the draft Pacific Community Results Report 2019; and to agree on a revised schedule and approach for the development of the Pacific Community’s next strategic plan. 3. The Subcommittee Chair, Ms. Anne-Claire Goarant (New Caledonia), welcomed the Director-General, Dr Stuart Minchin and participants to the 8th meeting of the Subcommittee. She acknowledged several new representatives, from FSM, Fiji, PNG and Tonga. The Chair advised members that, due to COVID-19 demands, New Caledonia was transferring chair responsibilities to Mr Jimmy Naouna. 4.