247. Org Apra Amcos Correction.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Financial Report 30 June 2020

Australasian Performing Right Association Limited (a company limited by guarantee) and its controlled entity ABN 42 000 016 099 Annual Financial Report 30 June 2020 Australasian Performing Right Association Limited and its controlled entity Annual Report 30 June 2020 Directors’ report For the year ended 30 June 2020 The Directors present their report together with the financial statements of the consolidated entity, being the Australasian Performing Right Association Limited (Company) and its controlled entity, for the financial year ended 30 June and the independent auditor’s report thereon. Directors The Directors of the Company at any time during or since the financial year are: Jenny Morris OAM, MNZM Non-executive Writer Director since 1995 and Chair of the Board A writer member of APRA since 1983, Jenny has been a music writer, performer and recording artist since 1980 with three top 5 and four top 20 singles in Australia and similar success in New Zealand. Jenny has recorded nine albums gaining gold, platinum and multi-platinum status in the process and won back to back ARIA awards for best female vocalist. Jenny was inducted into the NZ Music Hall of Fame in 2018. Jenny is also a non-executive director and passionate supporter of Nordoff Robbins Music Therapy Australia. Jenny presents their biennial ‘Art of Music’ gala event, which raises significant and much needed funds for the charity. Bob Aird Non-executive Publisher Director from 1989 to 2019 Bob recently retired from his position as Managing Director of Universal Music Publishing Pty Limited, Universal Music Publishing Group Pty Ltd, Universal/MCA Publishing Pty Limited, Essex Music of Australia Pty Limited and Cromwell Music of Australia Pty Limited which he held for 16 years. -

COMMUNITY RADIO NETWORK PROGRAMS and CONTENT LIST - Content for Broadcast on Your Station

COMMUNITY RADIO NETWORK PROGRAMS AND CONTENT LIST - Content for broadcast on your station May 2019 All times AEST/AEDT CRN PROGRAMS AND CONTENT LIST - Table of contents FLAGSHIP PROGRAMMING Beyond Zero 9 Phil Ackman Current Affairs 19 National Features and Documentary Bluesbeat 9 Playback 19 Series 1 Cinemascape 9 Pop Heads Hour of Power 19 National Radio News 1 Concert Hour 9 Pregnancy, Birth and Beyond 20 Good Morning Country 1 Contact! 10 Primary Perspectives 20 The Wire 1 Countryfolk Around Australia 10 Radio-Active 20 SHORT PROGRAMS / DROP-IN Dads on the Air 10 Real World Gardener 20 CONTENT Definition Radio 10 Roots’n’Reggae Show 21 BBC World News 2 Democracy Now! 11 Saturday Breakfast 21 Daily Interview 2 Diffusion 11 Service Voices 21 Extras 1 & 2 2 Dirt Music 11 Spectrum 21 Inside Motorsport 2 Earth Matters 11 Spotlight 22 Jumping Jellybeans 3 Fair Comment 12 Stick Together 22 More Civil Societies 3 FiERCE 12 Subsequence 22 Overdrive News 3 Fine Music Live 12 Tecka’s Rock & Blues Show 22 QNN | Q-mmunity Network News 3 Global Village 12 The AFL Multicultural Show 23 Recorded Live 4 Heard it Through the Grapevine 13 The Bohemian Beat 23 Regional Voices 4 Hit Parade of Yesterday 14 The Breeze 23 Rural Livestock 4 Hot, Sweet & Jazzy 14 The Folk Show 23 Rural News 4 In a Sentimental Mood 14 The Fourth Estate 24 RECENT EXTRAS Indij Hip Hop Show 14 The Phantom Dancer 24 New Shoots 5 It’s Time 15 The Tiki Lounge Remix 24 The Good Life: Season 2 5 Jailbreak 15 The Why Factor 24 City Road 5 Jam Pakt 15 Think: Stories and Ideas 25 Marysville -

YEAR in REVIEW Australian Music Industry Based on a Strong the YEAR in REVIEW – Vision to Become a Globally Recognised Music Nation Powerhouse

YEAR IN REVIEW Australian music industry based on a strong THE YEAR IN REVIEW – vision to become a globally recognised music nation powerhouse. MESSAGE FROM CHIEF Financial Overview A record year for APRA AMCOS with group EXECUTIVE DEAN ORMSTON revenue breaking the $400m milestone, Brett Cottle AM retired as CEO in June 2018 after 28 rising by 8.7% from $386.7m to $420.2m, an years presiding over a period of extraordinary increase of $33.5m on the back of continued change and growth for the organisation. Over strong growth in consumer demand for music the past 6 months there have been many delivered digitally. ‘farewell’ events and acknowledgements For APRA, gross collections rose by 10.4% to of Brett’s contribution to APRA AMCOS, $323.3m (excluding AMCOS management the wider rights management and fees), while AMCOS revenue rose 3.3% to music industries, both locally and $95.9m. internationally. I would like to add my Operating expenses across the group – personal further thanks to Brett for comprising APRA pro forma costs, system being a leader unparalleled, and a development related costs, costs of generous mentor. administering AMCOS and stand-alone This year’s report highlights the AMCOS costs – were $57.1m, up 13.1% strength of the organisation’s from last year’s figure of $50.5m. economic performance, breadth of Despite the increased system member service, and commitment to development spend APRA Net improving our industry’s ecosystem. Distributable Revenue – the amount Critical to the health of our sector is available for distribution to a direct conversation and relationship members and affiliated societies – with Federal and State governments. -

EVENTS OUR CONSULTATION PROCESS with YOU Onemusic Australia Is Consulting with You and Would Like to Hear What You Think

EVENTS OUR CONSULTATION PROCESS WITH YOU OneMusic Australia is consulting with you and would like to hear what you think. This paper sets out the proposed rates to apply to events and performances where music is used. It covers APRA’s existing rates for National and other Event Promoters and PPCA’s Tariffs B, E2, E4 and X and simplifies those separate licences and schemes by providing a combined approach. It is relevant for concert promoters, event and festival promoters and producers, performance spaces and those running ad hoc events from time to time that are not covered under other OneMusic licence schemes. Some OneMusic licences, such as Places of Interest, Councils, Hotels also cover events, subject to certain thresholds, and for events outside those limits, the rates here apply. You can access information about those licences here. We realise it can be confusing to have to pay music licence fees to two organisations. Starting from mid-2019, OneMusic Australia will be the one organisation for all your music licensing needs, and you’ll be able to pay for your licence online. It’s not easy to build a single licence scheme that suits everyone, so we’ve come up with a proposal which builds on previous discussions with industry and where possible applies the same metrics to the one event. We’d like you to take a look and provide us with your feedback. Live Performance Australia have prepared a summary for their members (June 2019) and you can read this here. This paper covers the proposal for licensing for the following types of events: ■■ Promoted music events and festivals (including free events); ■■ General entertainment events where music is used but not the primary focus (including free events). -

Fitness Centre and Fitness & Wellbeing Instructors

FITNESS CENTRE AND FITNESS & WELLBEING INSTRUCTORS SIGN UP Licensing Enquiries 1300 162 162 [email protected] onemusic.com.au September 2021 NOW The Fitness Centre and Fitness and Wellbeing Instructors scheme is designed for our music used in Your licence explained a facility or when instructing clients in fitness, toning or strengthening. All Inclusive OR Background music Music in Classes You may have our music or music videos playing in go to page 2 for Location go to page 3 your gym, yoga studio, barre or Pilates studio, or go to page 3 perhaps you have an outdoor training session, boot camp or cross fit business or indoor aqua fitness For examples of how this licence works in practice, see page 7. sessions where our music is played. Your Zumba or For a guide on how to complete your Licence Agreement go to circuit class is likely to have our workout music, just as onemusic.com.au/easy our motivational music is often played in martial arts and boxing training. Where that music is controlled Draw on the power of music by OneMusic Australia, this scheme will cover all of these uses. 10% reduced feeling of exertion when music is listened to versus when no music playing. (1) Why do I need a OneMusic licence? During yoga and pilates participants prefer Shows your organisation respects and supports a moderate level of complexity in music (a songwriters and recording artists, our cultural simple rhythm and a lack of orchestration). (2) creators. Aerobics participants prefer simple (not 1 (2) Permission. If you use music that is complex) music. -

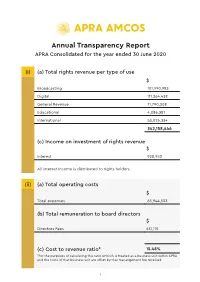

Annual Transparency Report APRA Consolidated for the Year Ended 30 June 2020

Annual Transparency Report APRA Consolidated for the year ended 30 June 2020 (i) (a) Total rights revenue per type of use $ Broadcasting 101,990,983 Digital 111,264,438 General Revenue 71,790,308 Educational 4,086,381 International 53,026,334 342,158,444 (c) Income on investment of rights revenue $ Interest 928,952 All interest income is distributed to rights holders. (ii) (a) Total operating costs $ Total expenses 65,944,523 (b) Total remuneration to board directors $ Directors Fees 631,115 (c) Cost to revenue ratio* 15.48% *For the purposes of calculating this ratio AMCOS is treated as a business unit within APRA and the costs of that business unit are offset by that manangement fee received. 1 (iii) (a) Total revenue attributed to rights holders $ Total revenue 343,280,631 Total expenses* 53,154,083 Net revenue owing to rights holders 290,126,548 *Total expenses include the value of management fee revenue netted off against the expenses incurred in earning that management fee revenue. It is the net surplus or deficit which is attributed to rights holders. (b) Total amount paid to rights holders $ Australian Writers 74,201,102 Australian Publishers 105,382,770 New Zealand Writers 8,478,483 New Zealand Publishers 160,176 Other rights holders 14,594,925 International affiliates 101,182,646 Total amount paid to rights holders 304,000,103 (c) Total amount attributed but not distributed $ Unidentified amounts and amounts in dispute 18,332,940 Amounts awaiting distribution 138,698,725 Total amount not distributed 157,031,666 2 (iv) Information about undistributed funds, including: (a) reasons why funds remain undistributed At the end of any financial year APRA will always have undistributed royalties. -

Panel Transcription Date

The State of Industry Report - Panel Transcription Date: 03/08/17 Moderator: Lars Brandle, Music Journalist, Billboard Magazine Speakers: Brett Cottle, CEO, APRA AMCOS; Dan Rosen, Chief Executive Officer; ARIA; Kim Tran, Director, Policy & Programs, Live Performance Australia LB: I would like to ask Brett, CEO of APRA AMCOS to open this and share with us some numbers. BC: Thanks Lars, I think in keeping with the timing we have I will be fairly brief in my comments. The perspective I am going to give you is of course that of the collecting society APRA AMCOS, which looks after the interests of songwriters and publishers, only a part of the ecosystem, but an important part. It is difficult to draw any conclusion other than that the industry is back in boom times, from the kinds of figures that I will refer to today. There are roughly three points I would like to make. The first is that digital revenue for songwriters and publishers is almost now at the level of revenue from the broadcast sector. In the year to 30 June 2017, we will be reporting across APRA and AMCOS digital revenue of $110 million. Included in digital are subscription and ad driven streaming services, digital downloads, video on demand and user generated content. The combined figure across those businesses this year will be $110 million. The figure from broadcasting this year, including all radio and television, across Australia and NZ will be $125 million. By way of indicating how we have travelled, two years ago digital revenue was $48 million and broadcast revenue was $122 million. -

Winslow Environmental Organization

SUBMISSION A MUSIC NATION – PRIORITIES FOR AUSTRALIA’S MUSIC INDUSTRY APRA AMCOS – WHO WE ARE APRA AMCOS has been representing Australian songwriters, composers and publishers since 1926. With 100,000 members across Australia and New Zealand, our membership includes the very best and brightest of established and emerging musical talent at home and around the globe. We administer rights on their behalf, supporting songwriters, composers and publishers in an industry that is a flagship of Australian culture and creativity, generating billions of dollars each year for the Australian economy. We are affiliated with similar collective management organisations around the world. So when Australian and New Zealand songs and compositions are played overseas, Australian and New Zealand writers get paid. We also help music customers in Australia and New Zealand access music from the rest of the world. We work in partnership with government to support the development and career paths within Australian music through the cornerstones of live music, digital distribution, local venues, education and the global stage. APRA AMCOS has successfully initiated and lead industry and government co- investment strategies, developing highly regarded capacity building programs, most notably; SongMakers, Live Music Office, SongHubs and SOUNDS AUSTRALIA. We advocate on behalf of music creators' rights and the Australasian music industry locally, nationally and internationally. Our Ambassador Program includes over 150 influential music creators representing the breadth and diversity of our membership, music publishers, and other industry stakeholders such as music venue operators and music managers. Collectively we promote the importance of music creators’ rights and our role in administering those rights to industry, all levels of government, the media and the wider community. -

Annual Report 2017

CONTENTS President’s Report 4 Treasurer’s Report 6 CEO’s Report 8 QMusic Program Report 10 QMusic Management Committee 16 QMusic Staff 19 Income & Expenditure Statement 22 Assets & Liabilities Statement 23 Statement of Cash Flows 24 3/374 Brunswick Street PO Box 878 Fortitude Valley QLD 4006 Notes to the Financial Statements 25 Australia T (07) 3257 0013 Statement by Members of the Committee 30 E [email protected] www.qmusic.com.au Independent Audit Report 31 Queensland Music Network Incorporated ABN 14 083 014 720 Disclaimer to the Detailed Income & Expenditure Statement 33 Promoting the artistic value, cultural worth and commercial potential of Queensland music. Detailed Income and Expenditure Statement 34 QMusic - The Queensland Music Network - is a registered non-profit association dedicated to developing, servicing and representing the Queensland music industry. QMusic acknowledges that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are the custodians of the land and recognise the disadvantage caused by colonisation and dispossession. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander music plays a critical role in the broader Australian music context and Australian culture overall. QMusic is committed to working with community to build opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists and music businesses. QMusic acknowledges the support and funding of the Queensland Government, Australia Council for the Arts and APRA AMCOS 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 3 PRESIDENT’S REPORT Like the wider music industry, QMusic has known its share of challenging times in more than two decades in existence. Those times have helped to place the positive moments into perspective. And 2017 will go down as a strong year for QMusic. -

Australia Council Support for Music

Inquiry into the Australian music industry Submission 98 AUSTRALIA COUNCIL FOR THE ARTS SUBMISSION TO THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON COMMUNICATIONS AND THE ARTS INQUIRY INTO THE AUSTRALIAN MUSIC INDUSTRY OCTOBER 2018 1 Inquiry into the Australian music industry Submission 98 Committee Secretary Standing Committee on Communications and the Arts PO Box 6021 Parliament House Canberra, ACT 2600 Dear Secretary, The Australia Council for the Arts welcomes the opportunity to provide this submission to the Inquiry into the Australian Music Industry. As the Australian Government’s principal arts funding and advisory body, the Council invests in artistic excellence through support for all facets of the creative process; increases awareness about the value of the arts; and is committed to the arts being more accessible to all Australians. Conducting, commissioning and publishing research into, and about, the arts is a key function under the Australia Council Act 2013.1 This submission outlines the role Council plays in supporting and promoting the diverse, excellent and energetic contemporary music culture. We would welcome the opportunity to discuss this further with you. Yours sincerely, Tony Grybowski Chief Executive Officer Australia Council for the Arts 1 Australia Council Act 2013 s.9 (Aust) 2 Inquiry into the Australian music industry Submission 98 Contents Executive summary 4 AUSTRALIA COUNCIL SUPPORT FOR MUSIC 7 FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY 9 Music practice 9 Disruption and resilience 11 Live music 14 Festivals 15 National -

The Australian Songwriter

The Australian Songwriter Issue 90, November 2012 First published 1979 The Magazine of The Australian Songwriters Association Inc. In this edition: Chairman’s Message Editor’s Message Top 25 Category Winners in the 2012 Australian Songwriting Contest 2012 Australian Songwriters Hall of Fame Inductee: Don Walker (Cold Chisel) ASA Member Profile: Alec Raymer ASA Member Profile: Kaitlyn Thomas Ten Keys To Unlock Creative Songwriting: Final Members News Sponsors Profiles ASA Member Profile: Kylie Stephens ASA Member Profile: Kathy Prosser New ASA Regional Co-Ordinator for Western Australia: Mike Cardy Festivals Roundup The Load Out Official Sponsors of the 2012 Australian Songwriting Contest About Us: o Aims of the ASA o History of the Association o Contact Us o Patron o Life Members o Directors o Regional Co-Ordinators Chairman’s Message All ASA Members, Here we go! November will be the most hectic month on the ASA Calendar as we build to our 2012 National Songwriting Awards Night. Pretty soon our Finals Judges will come up with the Top Ten place getters in every Category of the ASA 2012 Song Contest. They will of course be announced and feted on our special evening in December. It will be huge. Between now and then there is just enough time to check out the ASA November 2012 e-mag. Our Vice Chairman/Financial Officer/Editor Alan Gilmour has been slaving away as usual to bring you lots of interviews and stories about Members, along with helpful hints from some of Australia’s best Songwriters. The 2012 Song Contest Finalists are also listed. -

Music Festivals) Regulation 2019 and Gaming and Liquor Administration Amendment (Music Festivals) Regulation 2019

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Regulation Committee Liquor Amendment (Music Festivals) Regulation 2019 and Gaming and Liquor Administration Amendment (Music Festivals) Regulation 2019 Ordered to be printed 28 August 2019 according to Standing Order 231 Report 4 - August 2019 i LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Liquor Amendment (Music Festivals) Regulation 2019 and Gaming and Liquor Administration Amendment (Music Festivals) Regulation 2019 New South Wales Parliamentary Library cataloguing-in-publication data: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Council. Regulation Committee. Liquor Amendment (Music Festivals) Regulation 2019 and Gaming and Liquor Administration Amendment (Music Festivals) Regulation 2019 / Regulation Committee [Sydney, N.S.W.] : the Committee, 2019. [xii, 96] pages ; 30 cm. (Report no. 4 / Regulation Committee) “August 2019” Chair: Hon. Mick Veitch, MLC. ISBN 9781922258793 1. New South Wales. Liquor Amendment (Music Festivals) Regulation 2019. 2. New South Wales. Gaming and Liquor Administration Amendment (Music Festivals) Regulation 2019. 3. Liquor laws—New South Wales. 4. Music festivals—New South Wales. 5. Drinking of alcoholic beverages. I. Veitch, Mick. II. Title. III. Series: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Council. Regulation Committee. Report ; no. 4 344.9440541 (DDC22) ii Report 4 - August 2019 REGULATION COMMITTEE Table of contents Terms of reference v Committee details vi Chair's foreword vii Findings and recommendations ix Conduct of inquiry xi Chapter 1 Music festival licensing regulations 1 Background to the regulations