Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18 Jan 19 28 Feb 19

18 JAN 19 28 FEB 19 1 | 18 JAN 19 - 28 FEB 19 49 BELMONT STREET | BELMONTFILMHOUSE.COM What does it mean, ‘to play against type’? Come January/February you may find many examples. Usually it’s motivated by the opportunity to hold aloft a small gold-plated statue, but there are plenty memorable occasions where Hollywood’s elite pulled this trope off fantastically. Think Charlize Theron in Monster. Maybe Jim Carrey in Eternal Sunshine? Or Heath Ledger as Joker. These performances often come to dominate award season. Directors wrenching a truly transformative rendition out of their leads can be the difference between a potential big winner fading into obscurity, or being written into history. The class of 2019 appears particularly full of these turns. There might well be as much intrigue in figuring out which will be remembered, as in watching the performances themselves. ‘Unrecognisable as’ awards could go out to Margot Robbie as Elizabeth I in Mary Queen Of Scots; Melissa McCarthy in Can You Ever Forgive Me?; Nicole Kidman in Destroyer; Christian Bale as Dick Cheney in Vice. Others of course have been down this road before. Steve Carell has come a long, long way since Michael Scott and he looks tremendous in Beautiful Boy. And Matt Dillon, who we’ll see in The House That Jack Built, has always had a penchant for the slightly off-colour. There’s probably no one more off-colour than Lars von Trier. Screening for one night only. At Belmont Filmhouse we try to play against type as much as possible. -

O Cinema Interior De Philippe Garrel

philippe garrel philippe garrel o cinema interior de philippe garrel 1 Ministério da Cultura apresenta Banco do Brasil apresenta e patrocina philippe philippe garrel garrel philippe philippe ccbb rio de janeiro 17 out—5 nov 2018 ccbb brasília 30 out—18 nov 2018 Maria Chiaretti e Mateus Araújo organização 15 philippe garrel, aqui e agora 111 a criança-cinema maria chiaretti e mateus araújo alain philippon 21 um cinema do espetáculo íntimo: 119 amor em fuga as poéticas de philippe garrel alain philippon adrian martin 127 o povo que dorme: notas sobre o 35 “filmar a mulher amada, como fiz cinema de philippe garrel por dez anos, é algo em si bastante marcos uzal louco…”: sistema simbólico e virada narrativa na obra de philippe garrel 135 atores na alma nicole brenez cyril béghin 45 a maturidade de garrel 139 manifesto por um cinema violento adriano aprà philippe garrel 69 garrel: ali onde a fala se torna gesto 141 fragmentos de um diário thierry jousse philippe garrel 81 um filme “quebra-cabeça” 146 sendo o cinema apenas o fazendo sally shafto philippe garrel 97 o fulgor de um rosto 149 philippe garrel e serge daney: diálogo edson costa jr. 165 sinopses críticas 103 vida e morte da película luiz carlos oliveira jr. 209 filmografia Ministério da Cultura e Banco do Brasil apresentam O cinema interior de Philippe Garrel, a mais completa retrospectiva do ci- neasta francês já realizada no Brasil. Garrel aborda em sua trajetória cinematográfica a vida da juventude francesa, tendo como inspiração episódios de sua pró- pria biografia. Um dos nomes mais importantes do movimento pós-Nouvelle Vague ainda em atividade, o premiado cineasta tem 53 anos de carreira e segue filmando em formato 35mm, que é a marca de seu cinema. -

Philippe Garrel Rétrospective 18 Septembre – 20 Octobre

PHILIPPE GARREL RÉTROSPECTIVE 18 SEPTEMBRE – 20 OCTOBRE Les Baisers de secours L’ART DE L’INSTANT Digne successeur de la Nouvelle Vague, Philippe Garrel fait des films à la première personne. Le cinéma lui sert à restituer les pulsations de la vie. Vie affective avant tout. Le couple ou la difficulté de rester ensemble, scan- dés de film en film, de façon obsessionnelle. L’enfant, comme onde de choc. Et puis la politique qui entretient avec l’amour passionnel un lien immuable. Expérimental au commencement (Le Révélateur, La Cicatrice intérieure), son cinéma devient plus narratif à partir des Baisers de secours. L’introspection reste intacte. Séparation (J’entends plus la guitare) et fin des idéaux (Les Amants réguliers), autant de variations autour des femmes de sa vie, de la naissance à la mort de l’amour. La dernière fois, c’était il y a quinze ans. La précédente rétrospective de l’œuvre de Philippe Garrel à La Cinémathèque française date de juin 2004. Depuis, ce cinéma de l’expérience n’a ni faibli ni renoncé. N’a pas capitalisé, ni voulu s’édifier en quelconque règle. Il a continué, avec une régularité prodigieuse, à poursuivre une idée, à tisser une ligne de vie. Celle-ci a pris, plusieurs fois, de façon de plus en plus violente, la forme d’un doute, d’une remise en question. Les films se sont enchaînés, intriqués, répondus (avec ceci de drôle, chez Garrel : souvent, quand un film surgit, le titre du film précédent l’éclaire davantage : L’Ombre des femmes aurait pu s’appeler La Jalousie, L’Amant d’un jour pourrait facilement être titré L’Ombre des femmes. -

Of Gods and Men

A Sony Pictures Classics Release Armada Films and Why Not Productions present OF GODS AND MEN A film by Xavier Beauvois Starring Lambert Wilson and Michael Lonsdale France's official selection for the 83rd Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film 2010 Official Selections: Toronto International Film Festival | Telluride Film Festival | New York Film Festival Nominee: 2010 European Film Award for Best Film Nominee: 2010 Carlo di Palma European Cinematographer, European Film Award Winner: Grand Prix; Ecumenical Jury Prize - 2010Cannes Film Festival Winner: Best Foreign Language Film, 2010 National Board of Review Winner: FIPRESCI Award for Best Foreign Language Film of the Year, 2011 Palm Springs International Film Festival www.ofgodsandmenmovie.com Release Date (NY/LA): 02/25/2011 | TRT: 120 min MPAA: Rated PG-13 | Language: French East Coast Publicist West Coast Publicist Distributor Sophie Gluck & Associates Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Sophie Gluck Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 124 West 79th St. Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10024 110 S. Fairfax Ave., Ste 310 550 Madison Avenue Phone (212) 595-2432 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] Phone (323) 634-7001 Phone (212) 833-8833 Fax (323) 634-7030 Fax (212) 833-8844 SYNOPSIS Eight French Christian monks live in harmony with their Muslim brothers in a monastery perched in the mountains of North Africa in the 1990s. When a crew of foreign workers is massacred by an Islamic fundamentalist group, fear sweeps though the region. The army offers them protection, but the monks refuse. Should they leave? Despite the growing menace in their midst, they slowly realize that they have no choice but to stay… come what may. -

French Film Program Signs up 100 University

EMBASSY OF FRANCE – PRESS RELEASE French Film Program Signs up 100 th University TOURNÉES FESTIVAL IS A HIT ON AMERICAN CAMPUSES New York, February 7 —For the first time ever, more than 100 American universities are taking part in the Tournées Festival , which brings contemporary French films to campus screens . In all, 108 universities are participating, from 41 States and Puerto Rico. This year, the Tournées Festival will distribute approximately $180,000 in grants, with each participating institution receiving a grant of $1,800 to show a minimum of five films. First launched by the French-American Cultural Exchange (FACE) and the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in 1995 , the Tournées Festival was conceived to help isolated universities have access to new French films that are normally only distributed in big cities. Since its inception, the program has partnered with hundreds of universities and made it possible for more than 250,000 students to discover French-language films . It is hoped that participating universities will subsequently be able to launch their own self-sustaining French film festivals. To promote French-American cooperation, a key mission of FACE and the French Cultural Services , American professors are deeply involved in the selection process, both for the universities and the films. Three distinguished Americans selected which universities to support: Dudley Andrew , Professor of Film and Comparative Literature at Yale University , Livia Bloom , Assistant Curator at the Museum of the Moving Image, and Sonia Lee , Professor of French and African Literature at Trinity College. And, every year, Adrienne Halpern , co-founder of Rialto Films, Annette Insdorf , Professor of Graduate Film Studies at Columbia University, Richard Pena , Film Curator at the Lincoln Center, and Jean Vallier , Film Critic, help select the films that are included in the program. -

Following Is a Listing of Public Relations Firms Who Have Represented Films at Previous Sundance Film Festivals

Following is a listing of public relations firms who have represented films at previous Sundance Film Festivals. This is just a sample of the firms that can help promote your film and is a good guide to start your search for representation. 11th Street Lot 11th Street Lot Marketing & PR offers strategic marketing and publicity services to independent films at every stage of release, from festival premiere to digital distribution, including traditional publicity (film reviews, regional and trade coverage, interviews and features); digital marketing (social media, email marketing, etc); and creative, custom audience-building initiatives. Contact: Lisa Trifone P: 646.926-4012 E: [email protected] www.11thstreetlot.com 42West 42West is a US entertainment public relations and consulting firm. A full service bi-coastal agency, 42West handles film release campaigns, awards campaigns, online marketing and publicity, strategic communications, personal publicity, and integrated promotions and marketing. With a presence at Sundance, Cannes, Toronto, Venice, Tribeca, SXSW, New York and Los Angeles film festivals, 42West plays a key role in supporting the sales of acquisition titles as well as launching a film through a festival publicity campaign. Past Sundance Films the company has represented include Joanna Hogg’s THE SOUVENIR (winner of World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic), Lee Cronin’s THE HOLE IN THE GROUND, Paul Dano’s WILDLIFE, Sara Colangelo’s THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER (winner of Director in U.S. competition), Maggie Bett’s NOVITIATE -

L'amant D'un Jour

L’AMANT D'UN JOUR DIRECTED BY PHILIPPE GARREL // 2017 // FRANCE // 76 MIN Contact Information — U.S. Contact Information — U.K. Media: Julia Pacetti, JMP Verdant Publicity: Chris Boyd, Organic [email protected] / 718 399 0400 [email protected] / 020 3372 0970 Booking: Ian Stimler and Mika Kimoto, KimStim Booking: Martin Myers [email protected] / [email protected] [email protected] For all other questions, contact Lilly Riber, MUBI For all other questions, contact Sanam Gharagozlou, MUBI [email protected] / 803 479 3737 [email protected] / 07407 713406 Synopsis After a devastating breakup, the only place twenty-three-year old Lover for a Day premiered in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, where Jeanne has to stay in Paris is the small flat of her father, Giles. But it was awarded the SACD prize from the French Writers and Directors when Jeanne arrives, she finds that her father’s new girlfriend has Guild, and is an Official Selection of the 2017 New York Film Festival. moved in too: Arianne, a young woman her own age. Each is looking for their own kind of love in a city filled with possibilities. Reviews “Alluring and very elegantly crafted” Variety “A bittersweet, and intoxicating study of relationships in flux” The Film Stage “The images—exquisitely shadowed black-and-white 35mm— give the narrative a timelessness that is precisely the point of Garrel’s enterprise” Film Comment “Delectable” ScreenDaily “The film benefits from the collective contributions of four screenwriters… whose collective insights result in a beautiful -

Frontier of Dawn

Rectangle Productions presents Louis Garrel Laura Smet FRONTIER OF DAWN La frontière de l’aube a film by Philippe Garrel France – 105 min – B&W – 1.85 - Dolby SRD INTERNATIONAL PRESS WORLD SALES Viviana Andriani FILMS DISTRIBUTION 32 rue Godot de Mauroy 75009 PARIS 34, rue du Louvre | 75001 PARIS Tel/fax: +33 1 42 66 36 35 Tel: +33 1 53 10 33 99 In Cannes: In Cannes: Booth E5/F8 Cell: +33(0)6 80 16 81 39 Tel: +33 4 92 99 33 29 [email protected] www.filmsdistribution.com In Cannes SYNOPSIS Carole, a celebrity neglected by her husband, falls for François, a young photographer. Returning from a business trip the husband surprises them, and the lovers have to end their relationship. Carole gradually drifts into madness and commits suicide. One year later, a few hours before his wedding, François has a vision. It’s Carole, calling him from the other world… INTERVIEW WITH PHILIPPE GARREL How do you explain the title, Frontier of Dawn? While I was writing it, the film was called Heaven of the Angels, an expression I found in Blanche ou l’oubli by Louis Aragon. I liked it a lot but I was put off by the neo-Catholic side. And one night, at four in the morning, I came up with Frontier of Dawn, which evoked both the suicide and the ghost themes. I made the film with this title in mind and it gave me the key to each scene. Maybe the title is too deliberately poetic. I knew a director, Pierre Romans, who said an actor must never act poetic and to be poetic, you have to act in a realistic manner, with a trivial element. -

2015 Euro-In Film

19th festival of the european 19. фестивал европског and independent film и независног филма novi sad - serbia,, 4 - 28. 12. 2015. нови сад - србија,, 4 - 28. 12. 2015. 19. Фестивал европског и независног филма ЕУРО-ИН ФИЛМ 2015 EУРO-ИН ФИЛM je прoмoтoрни и прoмoтивни фeстивaл eврoпскe филмскe културe и умeтнoсти кojи прoмoвишe aктуeлнoсти у eврoпскoм и нeзaвиснoм прoфeсиoнaлнoм филму; - Рeaфирмишe успeшнe филмoвe и мaнифeстaциje из мeђунaрoднe културнe рaзмeнe и сaрaдњe; - Прoмoвишe, кoнстaтуje или oткривa тeндeнциje рaзличитих врстa eврoпскoг и нeзaвиснoг филмскoг ствaрaлaштвa у сфeри пoкрeтних звучних сликa, и oбeлeжaвa вaжнe jубилeje филмa; - Оргaнизуje дискусиje сa кoмпeтeнтним учeсницимa o виђeним филмoвимa и њихoвим aктeримa; - Афирмишe дeлa нoвoсaдских филмских рaдникa кoja прeвaзилaзe лoкaлнe грaницe; - Прoмoвишe eврoпскe филмoвe нa свим стaндaрдним нoсaчимa сликe и тoнa из свих грaнa eксплoaтaциje, a прeфeрирa нoвe тeхнoлoгиje сликe и звукa; - Стимулишe диустрибутeрe свих врстa филмскe eксплoaтaциje дa дистрибуирajу eврoпскe и нeзaвиснe филмoвe; - Стимулишe биoскoпe и TВ дa прикaзуjу eврoпскe и нeзaвиснe филмoвe; - Прoмoвишe нoву врeдну филмску литeрaтуру и филмску издaвaчку дeлaтнoст; - Пoдстичe и aфирмишe нaучнo и стручнo истрaживaњe и кooпeрaциjу нaучнe и стручнe мисли у oблaсти eврoпскoг и нeзaвиснoг филмa путeм oргaнизaциje сврсисхoдних тeмaтских скупoвa, рaдиoницa, суфинaнсирaњa и других oбликa пoдршки нaучним пoдухвaтимa - Оргaнизуje излoжбe пoсвeћeнe eврoпскoм и нeзaвиснoм филму; - Пoдсeћa нa кoрeнe истински врeднoг филмскoг ствaрaлaштвa, сa oсвртoм нa нaшe пoднeбљe; итд. EУРO-ИН ФИЛM je фeстивaл oтвoрeнe фoрмe и сaдржaja сa увeк oтвoрeним срдaчним пoзивoм свим дoбрoнaмeрницимa eврoпскoг и нeзaвиснoг филмa нa кoнструктивну сaрaдњу. Будући истински прaзник филмa, нe тeжи кoнкурeнциjи или кoнфрoнтaциjи сa oстaлим фeстивaлимa и филмскиим прoмoтeримa у Србиjи, Eврoпи и филмскoм свeту уoпштe, jeр у њимa види сaрaдникe нa сличнoм пoслу a нe кoнкурeнтe. -

Eric Caravaca Esther Garrel Louise Chevillotte a Film By

SAÏD BEN SAÏD & MICHEL MERKT PRESENT ERIC CARAVACA ESTHER GARREL LOUISE CHEVILLOTTE CRÉDITS NON CONTRACTUELS CRÉDITS (L’AMANT D’UN JOUR) A FILM BY PHILIPPE GARREL PHOTOS : © 2016 GUY FERRANDIS / SBS FILMS PHOTOS : © 2016 GUY FERRANDIS / SBS FILMS FILMOGRAPHY PHILIPPE GARREL 2017 LOVER FOR A DAY 2014 IN THE SHADOW OF WOMEN 2013 JEALOUSY In Competition, Venice 2013 2011 THAT SUMMER In Competition, Venice 2011 2005 FRONTIER OF DAWN Official Selection, Cannes 2008 2004 REGULAR LOVERS Silver Lion, Venice 2005 Louis Delluc award 2005 FRIPESCI Prize European Discovery, 2006 2001 WILD INNOCENCE International Critics’ Award, Venice 2001 1998 NIGHT WIND 1995 LE CŒUR FANTÔME films together without the lights being brought up 1993 LA NAISSANCE DE L’AMOUR between them. Before that, Athanor had been SYNOPSIS 1990 J’ENTENDS PLUS LA GUITARE attacked by a critic, who said I was banging my This is the story of a father, his 23-year-old Silver Lion, Venice 1991 head against a wall, against the obvious fact that daughter, who goes back home one day because 1988 LES BAISERS DE SECOURS she has just been dumped, and his new girlfriend, cinema was movement. La Cicatrice was tracking who is also 23 and lives with him. shots and music. Athanor was silence and still 1984 ELLE A PASSÉ TANT D’HEURES shots. Then it was back to Le Berceau with Ash SOUS LES SUNLIGHTS Ra Tempel’s music. So Athanor worked fine as an 1984 RUE FONTAINE (short) interlude between two parts of a concert. This 1983 LIBERTÉ, LA NUIT DIRECTOR’S NOTE time, it is a trilogy; the films are not made to be Perspective Award, Cannes 1984 screened together. -

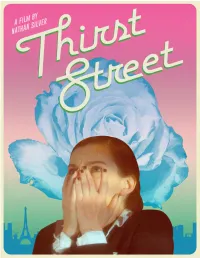

Thirst Street Press-Notes-Web.Pdf

A PSYCHOSEXUAL BLACK COMEDY Press Contacts: Kevin McLean | [email protected] Kara MacLean | [email protected] USA/FRANCE / 2017 / 83 minutes / English with French Subtitles / Color / DCP + Blu-ray Alone and depressed after the suicide of her lover, American flight attendant Gina (Lindsay Burdge, A TEACHER) travels to Paris and hooks up with nightclub bartender Jerome (Damien Bonnard, STAYING VERTICAL) on her layover. But as Gina falls deeper into lust and opts to stay in France, this harmless rendezvous quickly turns into unrequited amour fou. When Jerome’s ex Clémence (Esther Garrel) reenters the picture, Gina is sent on a downward spiral of miscommunication, masochism, and madness. Inspire by European erotic dramas from the 70’s, THIRST STREET burrows deep into the delirious extremes we go to for love. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT THIRST STREET brings together two of my longest-standing, most nagging obsessions: France and Don Quixote. I spent my junior year of high school as an exchange student in France, in a foolish attempt to live out my dream of being a French poet. I realized within days that I wasn’t French (and never would be) and that poetry wasn’t for me, but nearly two decades later, I still find myself just as obsessed with the place. Our protagonist Gina is my Quixote, unflinching in her quest to find that most important (and ridiculous) thing: love. The emotions of THIRST STREET are just as hysterical as those in my last few movies, but the style here is much more fluid and deliberate, with surreal lighting increasingly threatening to devour the picture. -

Lit Et Horizontalité Dans Le Cinéma De Philippe Garrel Guillaume Descave

Lit et horizontalité dans le cinéma de Philippe Garrel Guillaume Descave To cite this version: Guillaume Descave. Lit et horizontalité dans le cinéma de Philippe Garrel. Art et histoire de l’art. 2014. dumas-01059767 HAL Id: dumas-01059767 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01059767 Submitted on 1 Sep 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Paris 1- Panthéon – Sorbonne. UFR 04 Directeur de mémoire : José MOURE Deuxième année de MASTER RECHERCHE CINEMA Guillaume DESCAVE - N° étudiant : 11135308 [email protected] Année universitaire : 2013 - 2014 Date de dépôt : 16/05/2014 Lit et horizontalité dans le cinéma de Philippe Garrel Université Paris 1- Panthéon – Sorbonne. UFR 04 Université Paris 1- Panthéon – Sorbonne. UFR 04 Directeur de mémoire : José MOURE Deuxième année de MASTER RECHERCHE CINEMA Guillaume DESCAVE - N° étudiant : 11135308 06, petite rue des Jardins, 42190 CHARLIEU Tél : 06-17-95-57-02 [email protected] Année universitaire : 2013 - 2014 Date de dépôt : 16/05/2014 Lit et horizontalité dans le cinéma de Philippe Garrel 2 RESUME : Lit et horizontalité dans le cinéma de Philippe Garrel. Le lit comme figure récurrente chez Garrel.