The Development and Improvement of Instructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jane Hutt: Businesses That Have Received Welsh Government Grants During 2011/12

Jane Hutt: Businesses that have received Welsh Government grants during 2011/12 1 STOP FINANCIAL SERVICES 100 PERCENT EFFECTIVE TRAINING 1MTB1 1ST CHOICE TRANSPORT LTD 2 WOODS 30 MINUTE WORKOUT LTD 3D HAIR AND BEAUTY LTD 4A GREENHOUSE COM LTD 4MAT TRAINING 4WARD DEVELOPMENT LTD 5 STAR AUTOS 5C SERVICES LTD 75 POINT 3 LTD A AND R ELECTRICAL WALES LTD A JEFFERY BUILDING CONTRACTOR A & B AIR SYSTEMS LTD A & N MEDIA FINANCE SERVICES LTD A A ELECTRICAL A A INTERNATIONAL LTD A AND E G JONES A AND E THERAPY A AND G SERVICES A AND P VEHICLE SERVICES A AND S MOTOR REPAIRS A AND T JONES A B CARDINAL PACKAGING LTD A BRADLEY & SONS A CUSHLEY HEATING SERVICES A CUT ABOVE A FOULKES & PARTNERS A GIDDINGS A H PLANT HIRE LTD A HARRIES BUILDING SERVICES LTD A HIER PLUMBING AND HEATING A I SUMNER A J ACCESS PLATFORMS LTD A J RENTALS LIMITED A J WALTERS AVIATION LTD A M EVANS A M GWYNNE A MCLAY AND COMPANY LIMITED A P HUGHES LANDSCAPING A P PATEL A PARRY CONSTRUCTION CO LTD A PLUS TRAINING & BUSINES SERVICES A R ELECTRICAL TRAINING CENTRE A R GIBSON PAINTING AND DEC SERVS A R T RHYMNEY LTD A S DISTRIBUTION SERVICES LTD A THOMAS A W JONES BUILDING CONTRACTORS A W RENEWABLES LTD A WILLIAMS A1 CARE SERVICES A1 CEILINGS A1 SAFE & SECURE A19 SKILLS A40 GARAGE A4E LTD AA & MG WOZENCRAFT AAA TRAINING CO LTD AABSOLUTELY LUSH HAIR STUDIO AB INTERNET LTD ABB LTD ABER GLAZIERS LTD ABERAVON ICC ABERDARE FORD ABERGAVENNY FINE FOODS LTD ABINGDON FLOORING LTD ABLE LIFTING GEAR SWANSEA LTD ABLE OFFICE FURNITURE LTD ABLEWORLD UK LTD ABM CATERING FOR LEISURE LTD ABOUT TRAINING -

27 June 07 July

27 JUNE TO 07 JULY TWENTY NINETEEN Recommended Retail Price: R75 4 Festival Messages 6 Acknowledgements 9 Standard Bank Young Artist Award Winners 16 2018 Featured Artist 20 Curatorial Statement & Curatorial Team 22 Curated Programme 27 Main Programme 155 Fringe Programme 235 Travel and Accommodation 236 Booking Procedures 238 Index 241 Map We will be publishing an update to our Programme which will be available in Grahamstown throughout the Festival, at all of our Box Offices and Information Kiosks. This update will contain the latest possible information on performances and events, changes, cancellations and additional shows, a daily diary, map, local emergency services number, etc and is a must-have for all Festival-goers. Latest Programme changes and updates available at www.nationalartsfestival.co.za Images from left to right: Gas Lands (58), Moonless (31) and Wanderer (63) MAIN MAIN PROGRAMME FRINGE PROGRAMME Cover image: 27 155 Birthing Nureyev by Theatre Theatre leftfoot productions Director: Andre Odendaal Performer: Ignatius van Heerden 39 181 Designer: Gustav Steenkamp (Gustav-Henri Designstudio) Student Theatre Comedy Disclaimer: The Festival organisers have made 43 199 every effort to ensure that Comedy Illusion everything printed in this publication is accurate. However, mistakes and 46 203 changes do occur, and Public Art Family Theatre we do not accept any responsibility for them or for any inaccuracies 48 208 or misinformation within advertisements. Artists Family Theatre Dance provide images, logos and advertisements and we accept no responsibility for 57 214 the quality of reproduction Dance Music Theatre & Cabaret in this publication. 64 218 Visual & Performance Art Music Recital 82 220 Music Contemporary Music 105 224 Jazz Poetry 121 225 Film Festival Film 130 227 Critical Consciousness Visual Art 145 233 Creativate Spiritfest 4 Welcome to the Eastern Cape – the “Home of Legends”! 2019 sees the 45th edition of the National inspired. -

The Midlands Ultimate Entertainment Guide

Wolves & B'Cntry Cover March.qxp_Wolves & B/Country 23/02/2015 20:30 Page 1 WOLVERHAMPTON & BLACK WOLVERHAMPTON COUNTRY ON WHAT’S THE MIDLANDS ULTIMATE ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE WOLVERHAMPTON & BLACK COUNTRY ISSUE 351 ’ Whatwww.whatsonlive.co.uk sOnISSUE 351 MARCH 2015 GINA YASHERE MARCH 2015 SHOWING HER BEST BITS IN WOLVERHAMPTON CLAIRE SWEENEY talks Sex In Suburbia interview inside... PART OF MIDLANDS WHAT’S ON MAGAZINE GROUP PUBLICATIONS GROUP MAGAZINE ON WHAT’S MIDLANDS OF PART POP IN SPACE We Choose To Go To The Moon exhibition in Wolverhampton @WHATSONWOLVES WWW.WHATSONLIVE.CO.UK @WHATSONWOLVES INSIDE: FILM COMEDY THEATRE LIVE MUSIC VISUAL ARTS TUESDAY 17 - SATURDAY 21 MARCH EVENTS FOOD & DRINK Box Office 01902 42 92 12 & MUCH MORE! BOOK ONLINE AT grandtheatre.co.uk Spring NEC A4:Layout 1 26/01/2015 14:59 Page 1 The ultimate stitching, knitting & crafting shows! THURS 19 - SUN 22 MARCH NEC, BIRMINGHAM OPEN 9.30AM - 5.30PM (SUN 5PM) BIGGEST SHOW EVER - OVER 300 EXHIBITORS! MR SELFRIDGE COSTUMES // INTERNATIONAL TEXTILE ARTIST SOPHIE FURBEYRE THE SEWING CLUB // ‘FRACTURED IMAGES’ QUILTING DISPLAY PAPERCRAFTS & CARDMAKING // KNITTING, QUILTING & STITCHING JEWELLERY MAKING & BEADING // CATWALK FASHION SHOWS FREE WORKSHOPS & DEMONSTRATIONS // PROGRAMME OF TALKS Buy tickets on-line www.ichfevents.co.uk SAVE UP TO or phone Ticket Hotline 01425 277988 Tickets: Adults £10.50 in advance, £12.50 on the door £2 OFF! EACH ADULT AND SENIOR TICKET Seniors £9.50 in advance, £11.50 on the door IF ORDERED BY 5PM MON 16 MARCH 2015 Contents March Region -

2019 AMHR All Stars

2019 ALL STARSTARS 1115 AMHR Aged Gelding, 3 & Older - Over 32" to 34" 1st 320591 SWAN LAKE'S ROYAL FLUSH Carrie Berger and Caleb Hatfield 87 1st 329775 HOPKINS THE JOKERS CAMEO APPEARANCE A Reed or J Moore or Cheyene Coker 87 1st 331592 PECOS EAST ALL DECKED OUT DUDE Lisa R or Daniel J Navrat 87 4th 313691 MICHIGAN'S PRIMARY VOTER Brian, Tracey, Tyler & Samantha Slagle 84 4th 331243 STRASSLEIN RED E TO RUMBLE Cheryl or Scott Lorenson 84 6th 345619 JSW SHOWKAYCES GHOST RIDER Thomas or Lydia Coleman 81 7th 334905 HAZEL HILL FARM JACK WITTMER David or Debra or Holly Robinson 78 8th 302834 GV MINI LUXURIES TOY VEYRON Leigh Lucas-Murray 72 8th 303924 VUE HAUS MAGIC LEGEND VH Savannah E or J Rochelle Pitts 72 8th 324505 OLYMPIAN LM HAWKS TRUE GRIT Yvonne Barnum 72 8th 331535 TIBBS INA TIZZI TANGO Jayme Hobbs 72 1116 AMHR Aged Gelding, 3 & Older, 32" & Under 1st 331173 EAGLESNEST ROGUES ICE ECLIPSE Linda or James Kint 540 2nd 307153 AKS ARISTOCRATS INVITATION ONLY Tanya Smeins-Wright 369 3rd 327300 LDS Z LIGHTNING NEMESIS Dena Worthington 345 4th 329887 MOUNTAIN MEADOWS DANTE Roberta Bedsworth or Adison or Alyvia and Allyse Dwerlkotte309 5th 281525 S BAR P'S BIG TIME ATTITUDE Sheila Steinfeldt 306 6th 332748 LIL IRON RIDGES RAVENS DREAM Terri Paul 213 7th 321862 S BAR P'S SWEET HEAT Makayla or Stephanie Coffey or Curtis Walser 150 7th 345694 NWR WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT Lonnie Perdue 150 9th 301409 LOTSAFUN TRU BLUE EYED BANDIT Helen Hubacek 135 10th 313421 LOTSAFUN WONDERS READY 2 RUMBLE Helen Hubacek 120 10th 326679 STARS GRENADE James or Alene -

Record Packet Copy

RECORD PACKET COPY STATE OF CALIFORNIA-THE RESOURCES AGENCY PETE WILSON, Governor CALIFORNIA COASTAl COMMISSION ORTH COAST AREA FREMONT, SUITE 2000 • AN FRANCISCO, CA 94105-2219 (415) 904-5260 Th6a Filed: January 14. 1998 49th Day: Continued Staff: Bi 11 Van Beckum Staff Report: May 28. 1998 Hearing Date: June 11 • 1998 Commission Action: STAFF REPORT: APPEAL SUBSTANTIAL ISSUE LOCAL GOVERNMENT: County of Humboldt DECISION: Approval with Conditions APPEAL NO.: A-1-HUM-98-08 APPLICANT: RICHARD JONES •• PROJECT LOCATION: 807 Upper Pacific Drive. Shelter Cove. Humboldt County. APN 109-362-24. PROJECT DESCRIPTION: Development of a 1,352-square-foot manufactured home with three bedrooms and four on-site parking spots. APPELLANT: Linda Yates SUBSTANTIVE FILE DOCUMENTS: Humboldt County Local Coastal Program; Humboldt County Coastal Development Permit No. CDP-56-95. SUMMARY OF STAFF RECOMMENDATION: NO SUBSTANTIAL ISSUE The staff recommends that the Commission, after public hearing. determine that no substantial issue exists with respect to the grounds on which the appeal has been filed because the appellant has not raised any substantial issue with the local government•s action and its consistency with the certified LCP. Two of the issues raised are not valid grounds for an appeal as they do not concern the consistency of the project as approved with the policies of the LCP or Coastal Act public access policies. While the appellant has raised two other valid issues regarding the protection of visual and scenic resources and • hazards. the project as approved by the County does not raise a substantial e APPEAL NO.: A-1-HUM-98-08 APPLICANT: RICHARD JONES Page 2 • issue with regard to compatibility with the character of the surrounding area or the protection of the scenic and visual qualities of coastal areas. -

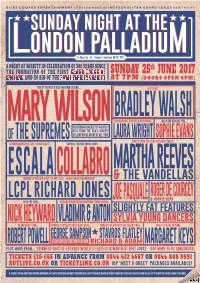

Collabro Escala

GILES COOPER ENTERTAINMENT LTD BY ARRANGEMENT WITH METROPOLITAN GRAND LODGE PROUDLY PRESENTS eeeeSUNDAYSUNDAY NIGHTNIGHT ATAT THETHEeeee LL ONDONONDON PALLADIUPALLADIUMM 8 Argyll St, Soho, London W1F 7TE A NIGHT OF VARIETY IN CELEBRATION OF 300 YEARS SINCE th THE FORMATION OF THE FIRST GRAND LODGE OF SUNDAY 25 JUNE 2017 ENGLAND AND IN AID OF THE ROYAL VARIETY CHARITY AT 7PM (DOORS OPEN 6PM) DIRECT FROM THE USA! MOTOWN LEGEND... HOSTED BY... BRADLEY WALSH MARY WILSON CLASSICAL NUMBER 1 ALBUM SELLING MEZZO SOPRANO... WEST-END MUSICAL STAR... PERFORMING A MEDLEY OF GREATEST HITS FROM THE USA’S BIGGEST of the supremes SELLING VOCAL GROUP OF ALL-TIME LAURA WRIGHT SOPHIE EVANS DIRECT FROM THE USA! MOTOWN LEGEND... GROUNDBREAKING ELECTRIC STRING QUARTET... MUSICAL THEATRE SUPER-GROUP... ESCALA COLLABRO MARTHA REEVES WINNER OF BRITAIN’S GOT TALENT 2016... MAGICIAN EXTRAORDINAIRE! & THE VANDELLAS LCPL RICHARD JONES roger de courcey & nookie bear 80’S POP ICON... ‘DUELLING’ VIOLIN VIRTUOSO BROTHERS FROM SLOVAKIA... SLIGHTLY FAT FEATURES NICK HEYWARD VLADIMIR & ANTON SYLVIA YOUNG DANCERS TV AND MOVIE STAR... WINNER OF BRITAIN’S GOT TALENT 2008... FINALISTS OF BRITAIN’S GOT TALENT 2009... IRISH CLASSICAL SOPRANO... GEORGE SAMPSON STAVROS FLATLEY ROBERT POWELL FINALISTS OF BRITAIN’S GOT TALENT 2013... RICHARD & ADAM MARGARET KEYS PLUS MORE FROM... GUINNESS BOOK OF RECORDS WORLD’S FASTEST HUMAN BEAT BOX! JC001 · AND MORE TO BE ANNOUNCED! TICKETS £15-£65 IN ADVANCE FROM 0844 412 4657 OR 0844 888 9991 RUTLIVE.CO.UK OR TICKETLINE.CO.UK VIP ‘MEET & GREET’ PACKAGES AVAILABLE! ALL PROCEEDS TO THE ROYAL VARIETY CHARITY (REGISTERED CHARITY NUMBER 206451) AND THE METROPOLITAN GRAND CHARITY’S TERCENTENARY APPEAL | SUBJECT TO AVAILABILITY. -

Commencement 2020 Commencement 2020

COMMENCEMENT 2020 COMMENCEMENT 2020 Celebrating the Class of 2020 Tuesday, December 15 Wayne State University 2020 Commencement 2 WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY PRESIDENT M. ROY WILSON Dear graduate, Congratulations! Graduating from Wayne State University is a remarkable achievement, so take time to celebrate all the hard work and sacrifice it took to get here. This year’s graduation looks different than it has in other years, but your accomplishments are in no way diminished because of it. As you arrive at this milestone, I’m confident your time at Wayne State has prepared you to reach many more. You’ve shown, through your flexibility and grace during difficult and unanticipated challenges, that you are well equipped to succeed in an ever-changing and diverse world. You’ll certainly benefit from your many hours of study and from the opportunities you’ve had to engage with the world outside the classroom from our campus in Detroit. This gives you a distinct advantage. Yet the richest reward from your time at Wayne State may be the wisdom you’ve gained that has made you a productive, compassionate and thoughtful citizen committed to making a difference in your community. Wayne State demanded your best because we wanted you to reach your full potential as a student. Today, we ask for one more thing: Keep in touch. Stay engaged with the university, and help a new generation access the transformative opportunities you have had here. We trust that your experience at Wayne State University has kindled a lifelong passion for learning. So instead of goodbye, I’ll say, “Until we meet again.” Now, more than ever, it’s important for us to remain Warrior Strong. -

Creative Commons and the Creative Industries Perspectives from the Creative Industries

Creative Commons and the Creative Industries Perspectives from the Creative Industries RICHARD NEVILLE, PROFESSOR RICHARD JONES, PROFESSOR BARRY CONYNGHAM AM AND PROFESSOR GREG HEARN Richard Neville is one person that I am sure does not need an introduction, but we must give him one. He is very well-known throughout the world as a social commentator and a futurist. We all know Richard from various initiatives he has been involved in from the Oz trials, right through to his social and political commentary in Australian television and media. I met Richard at a conference in Brisbane in 2004 and he said that he had been in India and had listened to Richard Stallman, who is the free software guru, talk about free and open source software. He said how fascinated he was with the concept. I asked him, ‘Have you heard about the Creative Commons?’ and he said, ‘Sort of.’ I said, ‘Would you come and speak at a conference we’re planning?’ and he said, ‘Yes, I’d like to. I really think these initiatives are very good’. As well as the paper by Richard Neville, a number of other experts also provide us with their experiences and thoughts regarding the adoption of Creative Commons in the Creative Industries. Professor Richard Jones presents reactions to open content licensing from the Australian independent film sector; Professor Barry Conyngham AM discusses his personal experiences as composer, educator and academic manager; and Professor Greg Hearn considers the implications of Creative Commons for the business side of the creative industries. Professor Brian Fitzgerald (Head, QUT Law School) 93 Perspectives from the Creative Industries40 RICHARD NEVILLE, PROFESSOR RICHARD JONES, PROFESSOR GREG HEARN AND PROFESSOR BARRY CONYNGHAM AM RICHARD NEVILLE In the Botanical Gardens, where I walked a few minutes ago to clear my head, there was a line of poetry on a plaque near a tree. -

Honoring the Class of 2018

Honoring the Class of 2018 UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Spring Commencement April 28, 2018 | Michigan Stadium Honoring the Class of 2018 SPRING COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 28, 2018 10:00 a.m. This program includes a list of the candidates for degrees to be granted upon completion of formal requirements. Candidates for graduate degrees are recommended jointly by the Executive Board of the Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies and the faculty of the school or college awarding the degree. Following the School of Graduate Studies, schools are listed in order of their founding. Candidates within those schools are listed by degree then by specialization, if applicable. Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies .....................................................................................................21 College of Literature, Science, and the Arts ..............................................................................................................33 Medical School .........................................................................................................................................................54 Law School ..............................................................................................................................................................55 School of Dentistry ..................................................................................................................................................57 College of Pharmacy ................................................................................................................................................58 -

Royal College of Nursing Group Structure and Relationships

Form AR21 Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 Annual Return for a Trade Union Name of Trade Union: Royal College of Nursing Year ended: 31st December 2020 List no: Head or Main Office address: 20 Cavendish Square London Postcode W1G 0RN Website address (if available) rcn.org.uk Has the address changed during the Yes No X ('X' in appropriate box) year to which the return relates? General Secretary: Donna Kinnair Telephone Number: Contact name for queries regarding Syed Hassan the completion of this return Telephone Number: 2076473689 E-mail: [email protected] Please follow the guidance notes in the completion of this return Any difficulties or problems in the completion of this return should be directed to the Certification Officer as below or by telephone to: 0330 109 3602 You should send the annual return to the following email address stating the name of the union in subject: For Unions based in England and Wales: [email protected] For Unions based in Scotland: [email protected] P1 Contents Trade Union's details…………………………………..………………………..……………………………….…….……..………………………………………………..1 Return of members…………………………………………..……………………………………………………...….…........…….….…………………..…….…………2 Change of officers…………………………………………………..……………………………………………….…………..………………..………….....………………2 Officers in post…………………………………………………..…………………………………………………………………....…..………………………………………2a General fund………………………………………………..……………………………………………...…..……….…..………..….....…………………….……..….…….3 Analysis of income from federation and other bodies and other income…….……….….....……………………….…………..…………4