Re-Envisaging Masculinity: the Struggle to Be Or Become A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dragon Magazine #182

Issue #182 Vol. XVII, No. 1 SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS Dragons: the lords of fantasy June 1992 9 Our annual tribute to our namesakeslong may they live! Publisher Not Cheaper by the Dozen Spike Y. Jones James M. Ward 10 Twelve of the DRAGONLANCE® sagas most egg-citing creations. Editor The Vikings' Dragons Jean Rabe Roger E. Moore 17 Linnorms: the first of a two-part series on the Norse dragons. The Dragons Bestiary Gregory Detwiler Associate editor 25 unhealthy branches of the dragon family tree. Dale A. Donovan Fiction editor F ICTION Barbara G. Young The Dragonbone Flute fiction by Lois Tilton Editorial assistant 84 He was a shepherd who loved musicbut he loved his audience more. Wolfgang H. Baur Art director R EVIEWS Larry W. Smith The Role of Computers Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk Lesser 55 From Mars to the stars: two high-powered science-fiction games. Production staff Gaye O'Keefe Angelika Lokotz Role-playing Reviews Lester Smith Tracey Zamagne Mary Roath 96 Now you can be the smallest of creatures or the most powerful. Through the Looking Glass Robert Bigelow Subscriptions\t 112 A collection of draconic wonders, for gaming or display. Janet L. Winters U.S. advertising O THER FEATURES Roseann Schnering Novel Ideas James Lowder 34 Two new horrific novels, spawned in the mists of Ravenloft. U.K. correspondent The Voyage of the Princess Ark Bruce A. Heard and U.K. advertising 41 This month, the readers questions take center stage. Bronwen Livermore The Wild, Wild World of Dice Michael J. DAlfonsi 45 Okay, so how many six-sided dice do you own? Kings of the Caravans Ed Greenwood 48 A land like the Forgotten Realms requires tough merchants! Dragonslayers on the Screen Dorothy Slama 62 Some handy guidelines for letting your computer be your DM. -

Iron Hans Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm

Page 1 of 7 136 Iron Hans Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm Once upon a time there was a king who had a great forest near his castle, full of all kinds of wild animals. One day he sent out a huntsman to shoot a deer, but the huntsman did not come back again. "Perhaps he has had an accident," said the king, and the following day he sent out two other huntsmen who were to search for him, but they did not return either. Then on the third day, he summoned all his huntsmen, and said, "Search through the whole forest, and do not give up until you have found all three." But none of these came home again either, nor were any of the hounds from the pack that they had taken with them ever seen again. From that time on, no one dared to go into these woods, and they lay there in deep quiet and solitude, and all that one saw from there was an occasional eagle or hawk flying overhead. This lasted for many years, when an unknown huntsman presented himself to the king seeking a position, and he volunteered to go into the dangerous woods. The king, however, did not want to give his permission, and said, "It is haunted in there. I am afraid that you will do no better than did the others, and that you will never come out again." The huntsman answered, "Sir, I will proceed at my own risk. I know nothing of fear." The huntsman therefore set forth with his dog into the woods. -

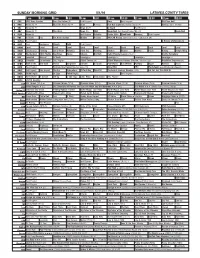

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Dragonlore Issue 14 09-12-2001

An A to Z of Dragonlore—Supplement (continued) GLAISTIG, basically a female Urisk, from the Scottish Highlands. GUIVRE, a toxic horned serpent that infested mediaeval France, it was extremely bashful and would flee from the sight of a naked male figure, a weakness that, once discovered, led to its total expulsion by bold young men. HEMICYNES, dog-headed humanoids from the Black Sea shores according to Dragonlore the Greeks. HYBRIDS, new monsters are still appearing in stories and in heraldry, that The Journal of The College of Dracology combine features from two or more animals but often do not have a specific name of their own. Examples are a fish with bird’s wings and a lion with peacock’s tail from Switzerland, a salmon with antlers and a wolf-headed raven from Number 14 St Andrew’s Day 1997 Scandinavia, and the supporters of the arms of the Canadian Heraldic Authority with upper half of a red raven and lower half of a polar bear. ICE-MAIDEN, perhaps a frozen mermaid. JACKALOPE, a hare or jack-rabbit with antlers, first noted in Germany but later a popular diversion in North America and much favoured by pranksters. KITCHI-AT’HUSIS, a forty foot long water serpent with antlers and venomous fangs that once lived in the waters of Boyden Lake in Maine, North America, but was beaten and eaten by a Weewilmekq; it was possibly a protean shaman. KUKULKAN, a Mayan feathered serpent perhaps related to Quetzalcoatl. LAMASSU, Assyrian man-headed winged lions and bulls used as gate guardians LINDORM, in Scandinavian heraldry, a kind of Wyvern probably the same as a Lindworm though in folklore the legs and wings were often missing. -

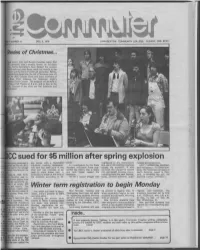

Csued for $5 Million After Spring Explosion Studentparalyzed in Day Earlier with a Flammable Ports

DEC. 5, 1979 LINN-BENTON COMMUNTIY COLLEGE ALBANY, ORE. 97321 ades of Christmas ... r around Linn and Benton Counties lately. But C personnel aren't exactly known as Scrooges r. Festivedecorations have decked the campus sallweekand even Santa made his rounds to the monsandthe Parent/Child Lab yesterday. Below, nyDanforthhelps trim the lab's Christmas tree. At , theLBCCConcert Choir and some members of Brass Choir rehearse for tomorrow night's 'stmasChoralConcert. The program will be held in TakenaHall Theatre at 8 p.m. and is free to the lie. Directorsof the show are Hal Eastburn and Ruppert. Csued for $5 million after spring explosion studentparalyzed in day earlier with a flammable ports. negligence in the manufacture riplegia and pneumonia. entlastMay at LBCC industrial flushing compound. An investigation by the State and use of the slushing chemical LBCC Pr~sident Ray Needham it againstthe college The tank had been built in the Accident Insurance Fund sup- caused the explosion. It also said the school's insurance com- icalmanufacturer for shop and was intended to be ported the theory that a spark contends the negligence caused pany, the Insurance Company of used to store diesel fuel. It and tank fumes caused the him permanent personal injury, North America, based in Port- sen,t9, 1535 N.W. contained no diesei at the time of explosion. including head and neck injuries, land, is handling the suit. He ., Corvallis, was in- the accident, according to re- Hansen's lawsuit alleges that coma, vertebra fractures, quad-' declined further comment.O 31whensparks from sawapparently ig- in an empty 200 tank nearby. -

Karate: Art of Tlie Orient Unifies Body and Spirit

S.A. Not Yet Famed NIT Overlooks Composer International Conducts Roadrunners at UTSA Page 3 Page 9 ^ Page 12 ents Pay Tribute To Prof greatest asset." said Dr B S. Thyagara lege should be It's a unique opportunity The $ 100 donation by Rick Rodrlgu*< "In addition to his teaching r**pon- Activ* in prof***ional organizations, lan, prolassor of chemistry lor students to immerse themselves in and John Smaidek Is on* concrete ex ilbilitl**, Thy*g*r«|an is deeply In Thyagarajan alto davot** hi* *nergy to Recently, two ot his lormer students an atmosphere of learning I try lo in ample of Thyagaralan* ability to in volved in Important r*ie*rch,"' univariity committ*** and (erve* •• paid tribute to Thyagarajans sue- spire them to take advantage of it — to spire and motlvat* his students Rodriguez noted, "We think •lumnl end faculty advit*r to th* UTSA chaptar of caai in taachlng by donating S100 to explore new ideas, to learn to think th* bu*in*** community *hould b* mor* th* Am*rlc*n Ch*mi*try Society. hia research efforts creatively and innovatively. These are "i-ie has taught us many things, t>oth «ctiv*iy lupportlv* of univ*rilty •fforts I tpprecitt* Rick *nd John'* oon- precious, valuable years whan students" inside and outside the art* of In th*«* *r***.'" tribullon." Thytgirajan (aid "Being able A profeuor at UTSA since its incep minda are fresh and dynamic They re In chamlstry.' said Sm«|d*k. Thy(g*r*j«n'8 main r****rch lnt*re*ts to encourag* my •tud*nt* to l**rn and tion in 1974. -

The Tales of the Grimm Brothers in Colombia: Introduction, Dissemination, and Reception

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 The alest of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception Alexandra Michaelis-Vultorius Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Michaelis-Vultorius, Alexandra, "The alet s of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 386. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE TALES OF THE GRIMM BROTHERS IN COLOMBIA: INTRODUCTION, DISSEMINATION, AND RECEPTION by ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my parents, Lucio and Clemencia, for your unconditional love and support, for instilling in me the joy of learning, and for believing in happy endings. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey with the Brothers Grimm was made possible through the valuable help, expertise, and kindness of a great number of people. First and foremost I want to thank my advisor and mentor, Professor Don Haase. You have been a wonderful teacher and a great inspiration for me over the past years. I am deeply grateful for your insight, guidance, dedication, and infinite patience throughout the writing of this dissertation. -

Fairy Tales in European Context Gen Ed Course Submission: for Inquiry – Humanitites

GER 103: Fairy Tales in European Context Gen Ed Course Submission: for Inquiry – Humanitites 2 lectures PLUS 1 discussion section: Professor Linda Kraus Worley 1063 Patterson Office Tower Phone: 257 1198 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesdays 10 - 12; Fridays 10 – 12 and by appointment FOLKTALES AND FAIRY TALES entertain and teach their audiences about culture. They designate taboos, write out life scripts for ideal behaviors, and demonstrate the punishments for violating the collective and its prescribed social roles. Tales pass on key cultural and social histories all in a metaphoric language. In this course, we will examine a variety of classical and contemporary fairy and folktale texts from German and other European cultures, learn about approaches to folklore materials and fairy tale texts, and look at our own culture with a critical-historical perspective. We will highlight key issues, values, and anxieties of European (and U.S.) culture as they evolve from 1400 to the present. These aspects of human life include arranged marriage, infanticide, incest, economic struggles, boundaries between the animal and human, gender roles, and class antagonisms. Among the tales we will read and learn to analyze using various interpretive methods are tales collected by the Brothers Grimm, by the Italians Basile and Straparola, by seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French writers such as D‘Aulnoy, de Beaumont, and Perrault, by Hans Christian Andersen and Oscar Wilde. We will also read 20th century re-workings of classical fairy tale motifs. The course is organized around clusters of Aarne, Thompson and Uther‘s ―tale types‖ such as the Cinderella, Bluebeard, and the Hansel-and-Gretel tales. -

Sam Shepard's Kicking a Dead Horse, Neil Labute's Reasons to Be Pretty, and Sarah Ruhl's Late: a Cowboy Song Scott C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Locating American Masculinity with(out)in the Male: Sam Shepard's Kicking a Dead Horse, Neil Labute's Reasons to Be Pretty, and Sarah Ruhl's Late: A Cowboy Song Scott C. Knowles Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE & DANCE LOCATING AMERICAN MASCULINITY WITH(OUT)IN THE MALE: SAM SHEPARD’S KICKING A DEAD HORSE, NEIL LABUTE’S REASONS TO BE PRETTY, AND SARAH RUHL’S LATE: A COWBOY SONG By SCOTT C. KNOWLES A Thesis submitted to the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2010 Copyright © 2010 Scott C. Knowles All Rights Reserved The members of the committee approve the thesis of Scott C. Knowles defended on April 1st 2010. __________________________________ Elizabeth A. Osborne Professor Directing Thesis __________________________________ Irma Mayorga Committee Member __________________________________ Dan Dietz Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With great appreciation for: Dr. Christine Frezza, for her support and mentorship; Michael Eaton, for his love of theatre and constant inspiration; Professor Richard Bugg, for acting as an intermediary between myself and Neil LaBute; Vanessa Banta for her constant support and encouragement; Ginae Knowles, for pushing me to accomplish all of my goals; Dr. Mary Karen Dahl, for her constant questioning, dedication, and mentorship; Dr. Irma Mayorga, for her guidance in writing and thinking; Professor Dan Dietz for his support; and, Dr. -

Like Crazy: a Writer’S Search for Information and Inspiration Sarah Lawrence SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2011 Like Crazy: A Writer’s Search for Information and Inspiration Sarah Lawrence SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Inequality and Stratification Commons, Psychiatric and Mental Health Commons, and the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, Sarah, "Like Crazy: A Writer’s Search for Information and Inspiration" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1002. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1002 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Like Crazy A Writer’s Search for Information and Inspiration Sarah Lawrence SIT Morocco, Spring 2011 Multiculturalism and Human Rights Advisor: Abdelhey Diouri Abstract I began this project with the sole aim of learning about the experience of the mentally handicapped in Morocco and the treatment and care options available to their families. However, with my independent study project on hold until I could find an advisor, I began brainstorming a Moroccan-themed fantasy story. Once I started my field research, many of my findings and observations about modern and traditional healing practices for the mentally disabled in the context of the Moroccan family enriched my developing world. Acknowledgements I doubt that I would have been able to get started on my independent study project if Abdelhey Moudden had not sat down with me several times to give me suggestions and help me find an advisor. -

Notice . of Six Norwegian Powder-Horns in the Museum, Carved with Subjects Fro E Romancem Th Charle E Th F So - Magne Cycle Y Georgb

VI. NOTICE . OF SIX NORWEGIAN POWDER-HORNS IN THE MUSEUM, CARVED WITH SUBJECTS FRO E ROMANCEM TH CHARLE E TH F SO - MAGNE CYCLE Y GEORGB . BLACKV E , ASSISTAN MUSEUME TH N I T . (PLATE II.) e Powder-HornTh s describe e followinth n i d g paper, although com- paratively modern f peculiao e ar , r interes accounn e o figuret th d f o tan s inscriptions carve theme greaten do Th . r numbe f theso r e figures refer heroee e Charlemagnth th o f t o s e cycl f romanceseo e storie,th f whosso e deeds wer populao es Middle th n i r e Ages shows e placa , th ey n b whic h these romances have taken in the literature of Western Europe. Thus Frencd Ol hav e n e Chansonhw i th e de Roland, dating fro e beginmth - elevente ninth f go he twelft th century n i hd centuran , y translated into rhymed German vers Swabiaa y eb Englisd n Ol priest have n I he w eth . storie) Roland,(1 f o s ) Roland r Otuel,f (2 o Si d Vernagu, l ) an al (3 d an the fourteenth century. In Iceland and Scandinavia we have the prose romance Karlamagnus Saga Kappak o hans, dating fro e thirteentmth h e Farocenturyth n eI Island. have e balladsw th e s Carlo, Magnussa Dreimur and the Runsevals Struj or Roulands Qveaji; and in Flemish a few fragments have also been discovered Danisn I . have hw fifteentea h century translation of the French Chanson, entitled Kejser Karl Magnus, a popula e b sai o rt d boo o thit k s day. -

Dragonlore Issue 60 11-06-05

ROUGE DRAGON The little red dragons which dwell in the caves Deep under the mountains of Wales, They comfort themselves in the long, long night By telling the old, old tales; And they tell the tale of a wonderful king Dragonlore With a dragon gules on his helm, Who put down rapine and war and want; And his peace lay over the realm. The Journal of The College of Dracology And the dragons claim, from his dragon-crest All the dragons of Wales are descended; And they say, some day the king will return, Number 60 St Erkenwald’s Day 2005 And their long, long night will be ended. For the king will rule throughout all the land On Loegria’s ancient throne; And the serpent’s reign will be over and past, And the dragons come into their own, at last! The dragons will come by their own. From “Motley Heraldry” by C.W. Scott-Giles (London, n.d.) and kindly sent in by Mary Pierson. Scott-Giles was Fitzalan Extraordinary, and kindly signed my copy of his book, which I had forgotten all about until Mary reminded me. He was a superb heraldic artist, and illustrated all his own books and verses. (See the cover of No 1.) The Return of the “Dragon” Brand “With our thinning hair we notice how fashions change over the years. Shortly after the occupation, a quantity of enamelled cast-iron table-ware was discovered, and the favourite colours were mirror-finish, light blue and olive green. Nowadays fiery orange, chocolate and shiny black seem to be preferred, but why “Dragon” brand? Fire-proof, perhaps?” (Note – this entire section came in a dream.