Adapting Story Games for Group Therapy with Teens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAY 19Th 2018

5z May 19th We love you, Archivist! MAY 19th 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

Roll 2D6 to Kill

1 Roll 2d6 to kill Neoliberal design and its affect in traditional and digital role-playing games Ruben Ferdinand Brunings August 15th, 2017 Table of contents 2 Introduction: Why we play 3. Part 1 – The history and neoliberalism of play & table-top role-playing games 4. Rules and fiction: play, interplay, and interstice 5. Heroes at play: Quantification, power fantasies, and individualism 7. From wargame to warrior: The transformation of violence as play 9. Risky play: chance, the entrepreneurial self, and empowerment 13. It’s ‘just’ a game: interactive fiction and the plausible deniability of play 16. Changing the rules, changing the game, changing the player 18. Part 2 – Technics of the digital game: hubristic design and industry reaction 21. Traditional vs. digital: a collaborative imagination and a tangible real 21. Camera, action: The digitalisation of the self and the representation of bodies 23. The silent protagonist: Narrative hubris and affective severing in Drakengard 25. Drakengard 3: The spectacle of violence and player helplessness 29. Conclusion: Games, conventionality, and the affective power of un-reward 32. References 36. Bibliography 38. Introduction: Why we play 3 The approach of violence or taboo in game design is a discussion that has historically been a controversial one. The Columbine shooting caused a moral panic for violent shooter video games1, the 2007 game Mass Effect made FOX News headlines for featuring scenes of partial nudity2, and the FBI kept tabs on Dungeons & Dragons hobbyists for being potential threats after the Unabomber attacks.3 The question ‘Do video games make people violent?’ does not occur within this thesis. -

DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CHANGEFUL TALES: DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Aaron A. Reed June 2017 The Dissertation of Aaron A. Reed is approved: Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Chair Michael Mateas Michael Chemers Dean Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Aaron A. Reed 2017 Table of Contents List of Figures viii List of Tables xii Abstract xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1 Framework 15 1.1 Vocabulary . 15 1.1.1 Foundational terms . 15 1.1.2 Storygames . 18 1.1.2.1 Adventure as prototypical storygame . 19 1.1.2.2 What Isn't a Storygame? . 21 1.1.3 Expressive Input . 24 1.1.4 Why Fiction? . 27 1.2 A Framework for Storygame Discussion . 30 1.2.1 The Slipperiness of Genre . 30 1.2.2 Inputs, Events, and Actions . 31 1.2.3 Mechanics and Dynamics . 32 1.2.4 Operational Logics . 33 1.2.5 Narrative Mechanics . 34 1.2.6 Narrative Logics . 36 1.2.7 The Choice Graph: A Standard Narrative Logic . 38 2 The Adventure Game: An Existing Storygame Mode 44 2.1 Definition . 46 2.2 Eureka Stories . 56 2.3 The Adventure Triangle and its Flaws . 60 2.3.1 Instability . 65 iii 2.4 Blue Lacuna ................................. 66 2.5 Three Design Solutions . 69 2.5.1 The Witness ............................. 70 2.5.2 Firewatch ............................... 78 2.5.3 Her Story ............................... 86 2.6 A Technological Fix? . -

MARCH 1St 2018

March 1st We love you, Archivist! MARCH 1st 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Gaming Introduction/Schedule ...........................................4 Role Playing Games (Campaign) ........................................25 Board Gaming ......................................................................7 Campaign RPGs Grid ..........................................................48 Collectible Card Games (CCG) .............................................9 Role Playing Games (Non-Campaign) ................................35 LAN Gaming (LAN) .............................................................18 Non-Campaign RPGs Grid ..................................................50 Live Action Role Playing (LARP) .........................................19 Table Top Gaming (GAME) .................................................52 NDMG/War College (NDM) ...............................................55 Video Game Programming (VGT) ......................................57 Miniatures .........................................................................20 Maps ..................................................................................61 LOCATIONS Gaming Registration (And Help!) ..................................................................... AmericasMart Building 1, 2nd Floor, South Hall Artemis Spaceship Bridge Simulator ..........................................................................................Westin, 14th Floor, Ansley 7/8 Board Games ................................................................................................... AmericasMart Building 1, 2nd -

Wyrd Con Companion Book 2014, Edited by Sarah Lynne Bowman (Los Angeles, CA: Wyrd Con, 44

The Wyrd Con Companion Book 2014 Edited by Sarah Lynne Bowman, Ph.D. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. Tips for interacting with the Wyrd Con Companion Book: To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Use the latest version of Adobe Acrobat Reader The views, opinions, and statements expressed in the Wyrd Con Companion Book are solely those of the Red text (except names) links to the web if you are connected to the Internet contributors and not necessarily those of Wyrd Con, its affiliates, or the editors. You will need to trust the document for the links to work Join the discussion about The Wyrd Con Companion Book on Facebook: Text in blue will link to other articles in the document http://www.facebook.com/groups/390244477724076/ Clicking on will bring you to the Table of Contents WyrdCon 5: May 22-26 2014 in Los Angeles, California Wyrd Con 6: September 24-27, 2015 in Costa Mesa, California: http://wyrdcon.com/ 5 Table of Contents Foreward .................................................6 Playing With Myth: The Academic Section of Larping the Past: Research The Wyrd Con Companion Book ......94 Report on High-School Edu-Larp Introduction from the Editor ...................7 Applying Mythic Imagination to Live Action Role-play Michal/ Mochocki ............................132 Craig Page .......................................60 -

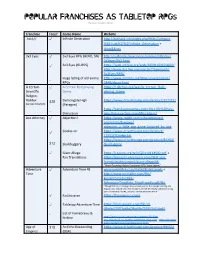

POPULAR FRANCHISES AS TABLETOP RPGS Revision 10 (Apr.2021)

POPULAR FRANCHISES AS TABLETOP RPGS Revision 10 (Apr.2021) Franchise Free? Game Name Website .hack// ✓ Infinite Generation http://dothack.info/index.php?title=Category %3A.hack%2F%2FInfinite_Generation + Odds&Ends 3x3 Eyes ✓ 3x3 Eyes RPG (HERO, SN) http://surbrook.devermore.com/worldbooks/ 3x3eyes/3x3.html ✓ 3x3 Eyes (GURPS) https://web.archive.org/web/20001109020600/ http://www.dca.fee.unicamp.br/~henriqmh/ 3x3Eyes/RPG/ Huge listing of old anime http://www.oocities.org/timessquare/arena/ - RPGs 2448/about.html A Certain ✓ A Certain Roleplaying https://1d4chan.org/wiki/A_Certain_Role- Scientific Game playing_Game Railgun, Raildex $20 Demongate High https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/127312/ See also Smallville. (Paragon) https://yarukizerogames.com/2011/02/10/role- - Discussion play-this-a-certain-scientific-railgun/ Ace Attorney ✓ Abjection! https://www.reddit.com/r/AceAttorney/ comments/8zwgwa/ abjection_a_little_rpg_game_inspired_by_ace ✓ Cookie Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/ 115517/Cookie-Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/84260/ $12 Skullduggery Skulduggery ✓ Giant Allege: https://i.4pcdn.org/tg/1520114144592.pdf + Fan Translations https://projects.inklesspen.com/fatal-and- friends/professorprof/giant-allege/#6 “Heart-Pounding Robot Courtroom RPG" from Japan!” Adventure ✓ Adventure Time 4E www.mediafire.com/?ia9628cdx6zacwb + Time http://www.mediafire.com/file/ kmxkml5mzduc994/ AdventureTimeBeta_PrintFriendly.pdf/file “Though I’m not releasing a new version just for this, people reading this original post should -

FEBRUARY 20Th 2018

February 20th We love you, Archivist! FEBRUARY 20th 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

Timeline Tree of Tabletop Role-Playing Games Pascal Martinolli

Timeline Tree of Tabletop Role-Playing Games Pascal Martinolli To cite this version: Pascal Martinolli. Timeline Tree of Tabletop Role-Playing Games. Donjons & Données probantes, Nov 2018, Montréal, Canada. 2019. halshs-02522264 HAL Id: halshs-02522264 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02522264 Submitted on 1 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial| 4.0 International License TTTTRPG - Timeline Tree of Tabletop Role-Playing Games, Celebrating more than 40 years of innovations in game designs Free Kriegsspiel movement Referee renders decisions Midwest Military Simulation Association past Strategos: A Series of American Games of War (...) [Totten CAL, 1890] 1960 on tactical experience only (not on rules) (1963) Pascal Martinolli (CC-BY-NC-SA) 2016-2019 [1860-1880] github.com/pmartinolli/TTTTRPG v.20200118 Diplomacy [Allan B. Calhamer, 1954-59] 1950 PC centered game-play fostering emergent roleplay Modern War in Miniature 1966 [Michael F Korns, 1966] Braunstein 1967 [David A Wesely, 1967] Hyboria [Tony Bath, 1968-1973?] PC centered play-by-post wargame 1968 Random personality creation Fantasy world building campaign. Long-lasting consequences of PC decisions on the game-world 1969 The Courrier [of NEWA] Strategos ’N’ two-pages set of rules 1970 One figure = One character Simulation & Gaming WARriors vs GAMErs (Perren S) Castle & Crusade Society Lake Geneva Tactical Studies Association [David A. -

Dungeon World the Bard

Dungeon World The Bard Dungeon World is a world of fantas- Your friends may carry blades of forged tic adventure. A world of magic, gods, steel but, Fighter, you are steel. While demons, Good and Evil. Brave heroes your traveling companions might moan venture into the most dangerous corners about their wounds over a campfire in of the land in search of gold and glory. the wilderness, you bear your scars with You are those heroes. You go where oth- pride. ers can’t or won’t. You conquer the un- You are the wall—let every danger beatable and laugh in the face of Death. smash itself to nothing on you. In the There are monstrous things lurking in end, you’ll be the last one standing. 1 the world. Are you ready to face them? The Paladin The Bard Dungeon Hell awaits. An eternity of torment in Sure,anadventurer’slifeisallopenroads fire or ice or whatever best suits the and the glory of coin and combat. Those sins of the damned throngs of Dungeon World tales that are told in every farmhand- World. All that stands between the pits filled inn have to have some ring of truth of that grim torture and salvation is you. to them, don’t they? Thesongs to inspire Holy man, armored war machine, tem- peasantry and royals alike—to soothe plar of the Good and the Light, right? the savage beast or drive men to a frenzy The Cleric may say his prayers at night to have to come from somewhere. the gods, dwelling in their heavens. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Tabletop Role-Playing Game Design Through a Pattern Language Software Model Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6c42m5zz Author Mayben, Alexander Montgomery Publication Date 2020 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6c42m5zz#supplemental License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ TABLETOP ROLE-PLAYING GAME DESIGN THROUGH A PATTERN LANGUAGE SOFTWARE MODEL A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in COMPUTATIONAL MEDIA by Alexander Mayben September 2020 The Thesis of Alexander Mayben is approved: Professor Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Chair Professor Michael Mateas Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Alexander Mayben 2020 Table of Contents List of Figures iv Abstract v Dedication vi Acknowledgments vii 1 Introduction 1 2 Related Work 6 2.1 On Pattern Languages . 6 2.2 On Tabletop Role-Playing Game Design . 8 3 Methods 10 3.1 Developing a Pattern Language . 10 3.2 Producing a System Design Tool . 12 4 Results 14 4.1 Pattern Language . 14 4.1.1 Theme . 14 4.1.2 Setting . 16 4.1.3 Mechanics . 17 4.2 Assemble . 23 4.2.1 Blockly Development Observations . 25 5 Conclusion 31 Bibliography 34 Appendix 37 iii List of Figures 4.1 An entity relationship diagram of the pattern language. 15 4.2 A diagram of a move pattern. 19 4.3 The Assemble interface. -

Analog Game Studies

ANALOG GAME STUDIES Aaron Trammell (Ed.), Evan Torner (Ed.), Emma Leigh Waldron (Ed.) Carnegie Mellon: ETC Press Pittsburgh, PA Copyright © by Aaron Trammell, Evan Torner, Emma Leigh Waldron, et al., and ETC Press 2016 http://press.etc.cmu.edu/ ISBN: 978-1-365-01547-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016905732 TEXT: The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NonDerivative 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/) IMAGES: All images appearing in this work are property of the respective copyright owners, and are not released into the Creative Commons. The respective owners reserve all rights. CONTENTS Foreword ix Reinventing Analog Game Studies: 1 Introductory Manifesto By Evan Torner, Aaron Trammell, Emma Leigh Waldron (Alphabetically) ANALYSIS “Fun in a Different Way”: Rhythms of 9 Engagement and Non-Immersive Play Agendas By Nick Mizer Strategies for Publishing Transformative 15 Board Games By Will Emigh Misogyny and the Female Body in Dungeons 23 & Dragons By Aaron Trammell The Playing Card Platform 34 By Nathan Altice Orientalism and Abstraction in Eurogames 55 By Will Robinson DOCUMENTATION From Where Do Dungeons Come? 67 By Aaron Trammell Larp-as-Performance-as-Research 75 By Emma Leigh Waldron Sex and Play-Doh: Exploring Women's 83 Sexuality Through Larp By Katherine Castiello Jones O Jogo do Bicho: Pushing the Boundaries of 92 Larp in Brazil By Luiz Falcão A Nighttime Tale of Xiros 118 By Adam Lazaroff Visual Design as Metaphor: The Evolution of a 126 Character