Report on the Commonwealth and Challenges to Media Freedom In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESS STATEMENT Arrests, Beatings and Dismissals Of

PRESS STATEMENT Arrests, Beatings and Dismissals of Journalists Underline Official and Corporate Arbitrariness: SAMDEN New Delhi, May 26, 2020 – The South Asia Media Defenders Network (SAMDEN) today cited detention of media professionals in Bangladesh, attacks on journalists in the Punjab, and the dismissal of a pregnant reporter in Assam state as part of a pattern of official and corporate arbitrariness against media in the region. In Bangladesh, SAMDEN noted that the government of Sheikh Hasina Wajed has used the controversial Digital Security Act (DSA), passed in 2018 amid opposition from national, international media and rights groups, to arrest or charge at least 20 journalists over the past month. In one case, a senior journalist vanished in March after a politician from the governing Awami League party filed a criminal defamation case against him. The reporter mysteriously turned up at the India-Bangladesh border nearly two months later and was slapped with three cases under the DSA while senior editor, Matiur Rahman Choudhury of Manabzamin also is accused in the case. SAMDEN underlining the spate of cases against journalists and media professionals, regards this as a clear and present danger to freedom of the media there and calls on the Sheikh Hasina government to free the arrested journalists, respect media rights and freedom and urges media associations worldwide to come out in support of the beleaguered media. “During a pandemic, a jail is the last place for a person to be, especially media professionals who are most needed at this time to provide factual, independent critical information to the public and to government as well as fearless reporting,” the Network said in a statement. -

30 November 2011 Berlin, Dhaka Friends: Wulff

PRESSE REVIEW Official visit of German Federal President in Bangladesh 28 – 30 November 2011 Bangladesh News 24, Bangladesch Thursday, 29 November 2011 Berlin, Dhaka friends: Wulff Dhaka, Nov 29 (bdnews24.com) – Germany is a trusted friend of Bangladesh and there is ample scope of cooperation between the two countries, German president Christian Wulff has said. Speaking at a dinner party hosted by president Zillur Rahman in his honour at Bangabhaban on Tuesday, the German president underlined Bangladesh's valuable contribution to the peacekeeping force. "Bangladesh has been one of the biggest contributors to the peacekeeping force to make the world a better place." Prime minister Sheikh Hasina, speaker Abdul Hamid, deputy speaker Shawkat Ali Khan, ministers and high officials attended the dinner. Wulff said bilateral trade between the two countries is on the rise. On climate change, he said Bangladesh should bring its case before the world more forcefully. http://bdnews24.com/details.php?id=212479&cid=2 [02.12.2011] Bangladesh News 24, Bangladesch Thursday, 29 November 2011 'Bangladesh democracy a role model' Bangladesh can be a role model for democracy in the Arab world, feels German president. "You should not mix religion with power. Tunisia, Libya, Egypt and other countries are now facing the problem," Christian Wulff said at a programme at the Dhaka University. The voter turnout during polls in Bangladesh is also very 'impressive', according to him. The president came to Dhaka on a three-day trip on Monday. SECULAR BANGLADESH He said Bangladesh is a secular state, as minority communities are not pushed to the brink or out of the society here. -

Amnesty International Report 2016/17

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2017 by Except where otherwise noted, This report documents Amnesty Amnesty International Ltd content in this document is International’s work and Peter Benenson House, licensed under a Creative concerns through 2016. 1, Easton Street, Commons (attribution, non- The absence of an entry in this London WC1X 0DW commercial, no derivatives, report on a particular country or United Kingdom international 4.0) licence. territory does not imply that no https://creativecommons.org/ © Amnesty International 2017 human rights violations of licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode concern to Amnesty International Index: POL 10/4800/2017 For more information please visit have taken place there during ISBN: 978-0-86210-496-2 the permissions page on our the year. Nor is the length of a website: www.amnesty.org country entry any basis for a A catalogue record for this book comparison of the extent and is available from the British amnesty.org depth of Amnesty International’s Library. concerns in a country. Original language: English ii Amnesty International Report 2016/17 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL -

Odhikar's Six-Month Human Rights Monitoring Report

Six-Month Human Rights Monitoring Report January 1 – June 30, 2016 July 01, 2016 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 4 A. Violent Political Situation and Local Government Elections ............................................................ 6 Political violence ............................................................................................................................ 7 141 killed between the first and sixth phase of Union Parishad elections ....................................... 8 Elections held in 21municipalities between February 15 and May 25 ........................................... 11 B. State Terrorism and Culture of Impunity ...................................................................................... 13 Allegations of enforced disappearance ........................................................................................ 13 Extrajudicial killings ..................................................................................................................... 16 Type of death .............................................................................................................................. 17 Crossfire/encounter/gunfight .................................................................................................. 17 Tortured to death: .................................................................................................................. -

English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh

Advances in Journalism and Communication, 2016, 4, 127-148 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajc ISSN Online: 2328-4935 ISSN Print: 2328-4927 Small Circulation, Big Impact: English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh Jude William Genilo1*, Md. Asiuzzaman1, Md. Mahbubul Haque Osmani2 1Department of Media Studies and Journalism, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2News and Current Affairs, NRB TV, Toronto, Canada How to cite this paper: Genilo, J. W., Abstract Asiuzzaman, Md., & Osmani, Md. M. H. (2016). Small Circulation, Big Impact: Eng- Academic studies on newspapers in Bangladesh revolve round mainly four research lish Language Newspaper Readability in Ban- streams: importance of freedom of press in dynamics of democracy; political econo- gladesh. Advances in Journalism and Com- my of the newspaper industry; newspaper credibility and ethics; and how newspapers munication, 4, 127-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajc.2016.44012 can contribute to development and social change. This paper looks into what can be called as the fifth stream—the readability of newspapers. The main objective is to Received: August 31, 2016 know the content and proportion of news and information appearing in English Accepted: December 27, 2016 Published: December 30, 2016 language newspapers in Bangladesh in terms of story theme, geographic focus, treat- ment, origin, visual presentation, diversity of sources/photos, newspaper structure, Copyright © 2016 by authors and content promotion and listings. Five English-language newspapers were selected as Scientific Research Publishing Inc. per their officially published circulation figure for this research. These were the Daily This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International Star, Daily Sun, Dhaka Tribune, Independent and New Age. -

Climate Change and the Media

THE HEAT IS ON CLIMATE CHanGE anD THE MEDIA PROGRAM INTERNATIONAL ConFerence 3-5 JUNE 2009 INTERNATIONALWorl CONFERENCED CONFERENCE CENTER BONN 21-23 JUNE 2010 WORLD CONFERENCE CENTER BONN 3 WE KEEP THINGS MOving – AND AN EYE ON THE ENVIRONMENT. TABLE OF CONTENTS THAt’s hoW WE GOGREEN. MESSAGE FROM THE ORGANIZERS 4 HOSTS AND SuppORTING ORGANIZATIONS 11 PROTECTING THE ENVIRONMENT 15 GLOBAL STudY ON CLIMATE CHANGE 19 PROGRAM OVERVIEw 22 SITE PLAN 28 PROGRAM: MONDAY, 21 JUNE 2010 33 PROGRAM: TuESDAY, 22 JUNE 2010 82 PROGRAM: WEDNESDAY, 23 JUNE 2010 144 SidE EVENTS 164 GENERAL INFORMATION 172 ALPHABETICAL LIST OF PARTICipANTS 178 For more information go to MAp 192 www.dhl-gogreen.com IMPRINT 193 21–23 JUNE 2010 · BONN, GERMANY GoGreen_Anz_DHL_e_Deutsche Welle_GlobalMediaForum_148x210.indd 1 30.03.2010 12:51:02 Uhr 4 5 MESSAGE FROM THE MESSAGE FROM THE HOST FEDERAL MiNISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS Nothing is currently together more than 50 partners, sponsors, Extreme weather, With its manifold commitment, Germany being debated more media representatives, NGOs, government crop failure, fam- has demonstrated that it is willing to accept than climate change. and inter-government institutions. Co-host ine – the poten- responsibility for climate protection at an It has truly captured of the Deutsche Welle Global Media Forum tially catastrophic international level. Our nation is known for the world’s atten- is the Foundation for International Dialogue consequences that its clean technology and ideas, and for cham- tion. Do we still have of the Sparkasse in Bonn. The convention is climate change will pioning sustainable economic structures that enough time to avoid also supported by Germany’s Federal Foreign have for millions of pursue both economic and ecological aims. -

![Seminar on Media and Human Rights Reporting on Asia's Rural Poor : November 24‑26, 1999, Bangkok : [List of Speakers and Participants]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1142/seminar-on-media-and-human-rights-reporting-on-asias-rural-poor-november-24-26-1999-bangkok-list-of-speakers-and-participants-1371142.webp)

Seminar on Media and Human Rights Reporting on Asia's Rural Poor : November 24‑26, 1999, Bangkok : [List of Speakers and Participants]

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Seminar on Media and Human Rights Reporting on Asia's Rural Poor : November 24‑26, 1999, Bangkok : [list of speakers and participants] 1999 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/93315 Downloaded on 24 Sep 2021 02:24:45 SGT ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Paper No. 2 ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Seminar on Media and Human Rights November 24-26,1999 Bangkok, Thailand LIST OF SPEAKERS/PARTICIPANTS ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Sheed SEMINAR ON MEDIA & HUMAN RIGHTS NOVEMBER 24-26. 1999. THAILAND Name of Speaker/Designation Organization DAY ONE 24/11/99 0900-1030: OPENING CEREMONY World Organization for Christian Communication (WACC) 367 Kennington Lane Pradip Ninan Thomas London SE115QY Director United Kingdom Studies & Publication Fax:441-717-35 0340 Sorajak Kasemsuvan Mass Communication Organization of Thailand Director General fax: 662-245 1851 United Nations Economic & Social Commission for the Asia & the Pacific (UN-ESCAP) The United Nations Building Rajadamnem Avenue Ms Kayoko Mizuta Bangkok 10200, Thailand Deputy Executive Secretary fax: 662-288 1000 "HUMAN RIGHTS REPORTING ON ASIA'S RURAL POOR (COUNTRY PRESENTATION FROM INDIA) 27/43 Sagar Sangam Bandra Reclamation, Bandra (W) Bombay 400 050, India tel: 9122-640 5829 /640 5829 email: [email protected] Mr P. Sainath OR: [email protected] Free lance Journalist fax: 9122-640 5829 1100-1145: "HUMAN RIGHTS REPORTING ON ASIA'S RURAL POOR" (COUNTRY PRESENTATION FROM MALAYSIA) School of Communication University Sains Malaysia 11800 Minden, Penang Malaysia tel: 0204-6577-888 ext. -

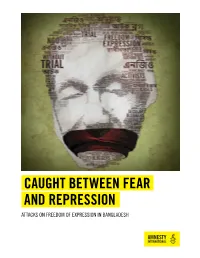

Caught Between Fear and Repression

CAUGHT BETWEEN FEAR AND REPRESSION ATTACKS ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN BANGLADESH Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Cover design and illustration: © Colin Foo Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 13/6114/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION TIMELINE 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & METHODOLOGY 6 1. ACTIVISTS LIVING IN FEAR WITHOUT PROTECTION 13 2. A MEDIA UNDER SIEGE 27 3. BANGLADESH’S OBLIGATIONS UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW 42 4. BANGLADESH’S LEGAL FRAMEWORK 44 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 57 Glossary AQIS - al-Qa’ida in the Indian Subcontinent -

BANGLADESH: from AUTOCRACY to DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values)

BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values) By Golam Shafiuddin THESIS Submitted to School of Public Policy and Global Management, KDI in partial fulfillment of the requirements the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2002 BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values) By Golam Shafiuddin THESIS Submitted to School of Public Policy and Global Management, KDI in partial fulfillment of the requirements the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2002 Professor PARK, Hun-Joo (David) ABSTRACT BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY By Golam Shafiuddin The political history of independent Bangladesh is the history of authoritarianism, argument of force, seizure of power, rigged elections, and legitimacy crisis. It is also a history of sustained campaigns for democracy that claimed hundreds of lives. Extremely repressive measures taken by the authoritarian rulers could seldom suppress, or even weaken, the movement for the restoration of constitutionalism. At times the means adopted by the rulers to split the opposition, create a democratic facade, and confuse the people seemingly served the rulers’ purpose. But these definitely caused disenchantment among the politically conscious people and strengthened their commitment to resistance. The main problems of Bangladesh are now the lack of national consensus, violence in the politics, hartal (strike) culture, crimes sponsored with political ends etc. which contribute to the negation of democracy. Besides, abject poverty and illiteracy also does not make it easy for the democracy to flourish. After the creation of non-partisan caretaker government, the chief responsibility of the said government was only to run the routine administration and take all necessary measures to hold free and fair parliamentary elections. -

Book Review Shamsul Hossain, Eternal Chittagong, Published By

Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh (Hum.), Vol. 59(2), 2014, pp. 385-387 Book Review Shamsul Hossain, Eternal Chittagong, published by Mahfuz Anam as part of The Daily Star’s Adamya Chattagrama Festival, 2012, 135 pages (no price mentioned). In 2012 the Daily Star in association with ‘Heritage Chatigrama’ held Adamya Chattagrama Festival. Eternal Chittagong is an outcome of that festival. It offers “an enlightened understanding of [Chittagong’s] present, through a better knowledge of the past….[and] for the future generations who will be inspired by the region’s glorious past and be motivated to work for its prosperous future” (p. xix) The nicely produced book is more than a catalogue of exhibits; it contains an enormous volume of materials related to Chittagong’s glorious past, and exposes to its readers the past history and heritage in a novel way. The cultural plurality is brought to the attention of the readers and researchers in such a way that can be considered a panoramic record of Chittagong’s past glory. The author is concerned about the poor state of heritage preservation and conservation in the city, and he has successfully focused on this point through photographs. A quick look at the book may give one the idea that it is ‘a coffee-table almanac’. This is hardly the case. The author attempts to present a chronological account from Chittagong’s pre-history to the history of the colonial period. But the book evolves in an interesting way: with a beautiful and high quality full-page photographs, with a note describing the object or building in English and Bangla on the adjacent page. -

Negotiating Modernity and Identity in Bangladesh

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 9-2020 Thoughts of Becoming: Negotiating Modernity and Identity in Bangladesh Humayun Kabir The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4041 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THOUGHTS OF BECOMING: NEGOTIATING MODERNITY AND IDENTITY IN BANGLADESH by HUMAYUN KABIR A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 HUMAYUN KABIR All Rights Reserved ii Thoughts Of Becoming: Negotiating Modernity And Identity In Bangladesh By Humayun Kabir This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________ ______________________________ Date Uday Mehta Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ ______________________________ Date Alyson Cole Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Uday Mehta Susan Buck-Morss Manu Bhagavan THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Thoughts Of Becoming: Negotiating Modernity And Identity In Bangladesh By Humayun Kabir Advisor: Uday Mehta This dissertation constructs a history and conducts an analysis of Bangladeshi political thought with the aim to better understand the thought-world and political subjectivities in Bangladesh. The dissertation argues that political thought in Bangladesh has been profoundly structured by colonial and other encounters with modernity and by concerns about constructing a national identity. -

Jefferson Fellows 1967 - 2017

JEFFERSON FELLOWS 1967 - 2017 (All participants are listed in the position they held when attending the Jefferson Fellowship.) AFGHANISTAN Del Irani Prime-time Presenter, Australia Network and Australian Nour M. Rahimi Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) News, Australia Assistant Editor, Kabul Times (2013 Jefferson Fellowships) Kabul (1972 Jefferson Fellowships) W. Rex Jory AUSTRALIA Associate Editor, The Advertiser Adelaide (1990 Jefferson Fellowships) Michael Eric Bachelard Victorian Political Reporter, The Australian Susan Lannin Victoria (2005 Fall Jefferson Fellowships) Business Journalist, Australian Broadcasting Corporation Ultimo (2015 Jefferson Fellowships) Rosslyn Beeby Science & Environment Reporter, The Canberra Times Philippa McDonald Canberra (2009 Fall Jefferson Fellowships) Senior Reporter, ABC TV News Australian Broadcasting Corporation Verona Burgess Sydney (2010 Spring Jefferson Fellowships) Public Administration Writer, Canberra Times Canberra (1993 Jefferson Fellowships) Jonathan Pearlman Foreign Affairs and Defense Correspondent Milton Cockburn The Sydney Morning Herald Leader Writer and Feature Writer Canberra ACT (2008 Fall Jefferson Fellowships) Sydney Morning Herald Sydney (1984 Jefferson Fellowships) Brian M. Peck Senior Journalist, Australian Broadcasting Commission Emma Mary Connors Sydney (1971 Jefferson Fellowships) Senior IT Writer, Australian Financial Review Sydney (2007 Spring Jefferson Fellowships) Iskhandar Razak Journalist, Producer, and Presenter Lee Duffield Australian Broadcasting Corporation Staff