Vpublic HEALTH REPORTS .V .OL~35 NOVEMBER 12, 1920 No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Forgotten Plague

AmericanHeritage.com / THE FORGOTTEN PLAGUE http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/2000/8/... December 2000 Volume 51, Issue 8 THE FORGOTTEN PLAGUE A MURDEROUS DISEASE WAS RAVAGING THE SOUTH. THEN ONE BRAVE AND DETERMINED DOCTOR DISCOVERED THE CURE—AND NOBODY BELIEVED HIM. BY DANIEL AKST Oblivion is a virtue in a disease. Cancer, AIDS, diabetes, and even tuberculosis are too much with us, but hardly anyone knows what pellagra is because the disfiguring deadly illness is virtually nonexistent in America today. For the first third of this century, pellagra was a scourge across the American South, killing thousands and afflicting hundreds of thousands more. Its cause was unknown, and there was no treatment, let alone cure. Victims were shunned like lepers, and by 1914 the sickness was a national scandal. The conquest of pellagra was a triumph of epidemiology over an affliction perhaps as ancient as the Bible, but it was also a triumph of one remarkable man, a medical Sherlock Holmes who fought ignorance, politics, and injustice as well as the disease. Even when the mystery of this preventable killer was solved, pellagra raged for another generation. It was as if the disease mocked science as crucial but insufficient. Pellagra is no longer a national health threat, and that is exactly why the experience of its conqueror is worth retelling. Pellagra was known as the disease of the three D’s: dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia. Victims suffered scaling, leprous skin, intestinal distress, lethargy, and depression. The trademark symptom was a butterfly rash—an ugly symmetrical blotch that spread across the victim’s face—marking him or her for all to see. -

Joseph Goldberger & the War on Pellagra

Joseph Goldberger & the War on Pellagra Dr. Joseph Goldberger & the War on Pellagra Pellagra no longer stalks the nation as it once did. But during the early part of the 20th-century, pellagra, a disease that results from a diet deficient in niacin, killed many poor Southerners. Dr. Joseph Goldberger, a physician in the U.S. government's Hygienic Laboratory, the predecessor of the National Institutes of Health, discovered the cause of pellagra and stepped on a number of medical toes when his research experiments showed that diet and not germs (the currently held medical theory) caused the disease. He also stepped on Southern pride when he linked the poverty of Southern sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and mill workers to the deficient diet that caused pellagra. Table of Contents Introduction The Early Years: An Immigrant Youth The Bright Young Dr. Goldberger Goldberger and the "Pellagra Germ" Ashes on the Potomac Acknowledgments Photography Credits Display Case in Building One Dr. Joseph Goldberger discovered the cause of pellagra, a disease resulting from a diet deficient in vitamin B. Pellagra killed many poor Southerners in the early part of the 20th century. Introduction Eighty years ago, long before Dr. C. Everett Koop and a new generation of public health professionals suffered social criticism in their public health pronouncements on AIDS, Dr. Joseph Goldberger, Surgeon in the United States Public Health Service, was doing much the same thing. Even as Koop has been critical of personal behavior and social policies that could put populations at risk of acquiring the AIDS virus, Goldberger warned Americans about the crucial link between poor nutrition as the result of poverty and the onset of a scourge known as pellagra. -

Pellagra Lesson Plan

DISEASE AND SOCIAL POLICY IN THE AMERICAN SOUTH: A Case Study of the Pellagra Epidemic GRADE LEVELS: 10th grade through second year of college/university. SUBJECTS: American History, Health, Rural History. SUMMARY: This lesson presents six activities in which students learn about two epidemics in American history and understand their social, economic, and political contexts, rather than a conventional medical history. In Activity 1 students reflect on their own conceptions about the longevity of Americans today and the factors that influence it. Activity 2 uses a timeline to introduce a case study in its historical context: the early-1900s pellagra epidemic in the American South. In Activities 3 and 4 students use primary sources to learn about the course of the pellagra epidemic. These activities lead up to Activity 5, in which students learn about the socioeconomic conditions in the South that led to the epidemic, write bills, and present their solutions to a model Congress set in 1920. In Activity 6 students use what they learn from the pellagra case study and compare pellagra to the Type II diabetes epidemic affecting the Pima and Tohono O’odham Indians of southern Arizona today. OBJECTIVES: • To learn about the socioeconomic conditions in the American South during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. • To practice analyzing and making deductions based on primary source documents. • To understand the socioeconomic factors that help explain why certain groups of Americans are, on average, sicker than others. TIME ALLOTMENT: Two to five class periods, depending on number of activities implemented. MATERIALS: • The documentary UNNATURAL CAUSES: Is Inequality Making Us Sick? and materials posted on its Web site at http://www.unnaturalcauses.org/ • Articles from The New York Times Archive, available free online: http://www.nytimes.com/ref/membercenter/nytarchive.html • Web access is required during part of Activity 5, but could be avoided by printing out the necessary documents beforehand. -

Prisoners As Human Subjects: a Closer Look at the Institute Of

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 2010 Prisoners as Human Subjects: A Closer Look at the Institute of Medicine's Recommendations to Loosen Current Restrictions on Using Prisoners in Scientific Research Osagie K. Obasogie UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation Osagie K. Obasogie, Prisoners as Human Subjects: A Closer Look at the Institute of Medicine's Recommendations to Loosen Current Restrictions on Using Prisoners in Scientific Research, 6 Stan. J. C.R. & C.L. 41 (2010). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/1359 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 41_82_OBASOGIE-PRINTER PROOF.DOC 11/9/10 4:30 PM ARTICLE PRISONERS AS HUMAN SUBJECTS: A CLOSER LOOK AT THE INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE’S RECOMMENDATIONS TO LOOSEN CURRENT RESTRICTIONS ON USING PRISONERS IN SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH Osagie K. Obasogie† There have been notable discussions within scientific literature, bioethics scholarship, and the popular press regarding the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) 2006 recommendations to the Department of Health and Human Services to loosen federal restrictions on using prisoners in biomedical and behavioral research. Yet there has been little dialogue among legal scholars about the recommendations’ potential impact on administrative policy. Supporters point to the growing need for clinical trial participants, ethicists’ changing perspectives, and greater institutional protections, while opponents point to past abuses and their likelihood to reoccur. -

NATIONAL LIBRARY of MEDICINE Reference Division

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE Reference Division NOTABLE CONTRIBUTIONS TO MEDICAL RESEARCH by PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE SCIENTISTS A Biobibliography to 1940 Compiled by Jeannette Barry U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE Public Health Service Washington, D. C. 1960 Public Health Service Publication No. 752 CONTENTS Page Preface iii Chronological Table: Notable Public Health Service Scientists vi John Fleetezelle Anderson 1 Charles Armstrong 3 Ida Albertina Bengtson 6 William Mansfield Clark 8 Barnett Cohen 11 Rolla Eugene Dyer 12 Alice Catherine Evans 14 Edward Francis 17 Wade Hampton Frost 19 Joseph Goldberger 21 Claude Silbert Hudson 25 Reid Hunt 27 Joseph Hoeing Kastle 30 James Payton Leake 32 Kenneth Fuller Maxcy 34 George Walter McCoy 36 Ralph Robinson Parker 41 Milton Joseph Rosenau 43 Louis Schwartz 46 Atherton Seidell 47 Maurice Isadore Smith 49 Roscoe Roy Spencer 51 Charles Wardell Stiles 53 Arthur Marston Stimson 56 Carl Voegtlin 58 William Buchanan Wherry 60 ABBREVIATIONS The journal title abbreviations in the bibliographies are those used in the Current List of Medical Literature and for older references, those used in the several series of the Index- Catalogue of the Library of the Surgeon General’s Office. Annotations in the references identified as quoted from “Bloomfield”, “Garrison”, “Kelly” or “Williams,” refer to numbers 1, 4, 5, and 11 in the general bibliography following the preface. ii PREFACE This series of brief bio-bibliographies presents a selection of books and articles by medical and scientific officers of the United States Public Health Service, most of whom worked in the Hygienic Laboratory (later the National Institute of Health) and in the Division of Scientific Research. -

Politics and Pellagra: the Epidemic of Pellagra in the U.S

THE YALE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE 65 (1992), 211-221 Politics and Pellagra: The Epidemic of Pellagra in the U.S. in the Early Twentieth Century ALFRED JAY BOLLET, M.D. Clinical Professor ofMedicine, Yale University School ofMedicine, New Haven, Connecticut; Vice-PresidentforAcademic Affairs, Danbury Hospital, Danbury, Connecticut Received December 11, 1991 The epidemic of pellagra in the first half of this century at its peak produced at least 250,000 cases and caused 7,000 deaths a year for several decades in 15 southern states. It also filled hospital wards in other states, which had a similar incidence but refused to report their cases. Political influences interfered, not only with surveillance of the disease, but also in its study, recognition of its cause, and the institution of preventive measures when they became known. Politicians and the general public felt that it was more acceptable for pellagra to be infectious than for it to be a form of malnutrition, a result of poverty and thus an embarrassing social problem. Retrospectively, a change in the method of milling cornmeal, degermination, which began shortly after 1900, probably accounted for the appearance of the epidemic; such a process was suggested at the time, but the suggestion was ignored. The story of the epidemic of pellagra in the United States, which occurred in the first half of the twentieth century, may remind people of contemporary events surrounding the AIDS epidemic, when social and political forces have affected medical research. To a very real extent, history has been repeating itself. The epidemic of pellagra, which caused over 3 million cases and 100,000 deaths in the U.S., has been largely forgotten, and the reason for the outbreak is not widely known, even though it is a phenomenon which caused a similar disease outbreak in the Far East (beriberi) beginning a few years earlier, and it could happen again. -

Pellagra in the American South

The Rise and Fall of Pellagra in the American South Karen Clay* Ethan Schmick† Werner Troesken‡ This draft: August 2016 Abstract No other nutrition-related disease in American history caused as many deaths as pellagra. The by-product of insufficient niacin consumption, pellagra reached epidemic proportions in the American South, killing roughly 7,000 Southerners annually at its peak in 1928. We document the rise and fall of pellagra in the American South and present three main findings. First, pellagra resulted, in part, from Southern agriculture’s heavy emphasis on cotton, which displaced local food production and effectively raised the price of niacin consumption. Evidence for this proposition derives in part from the arrival of the boll weevil. Although the boll weevil reduced Southern incomes and cotton production, it was also associated with increases in local food production and sharp reductions in pellagra. Second, pellagra was largely eliminated through voluntary fortification of cereal-grain products starting in 1937 and a series of state fortification laws passed in the 1940s. These laws, for the first time in Southern history, broke the strong positive correlation between cotton production and pellagra. Third, exposure to early-life interventions that reduced cotton production and/or increased niacin consumption were associated with improved stature and wages. These findings have important implications for our understanding of the economic history of the American South and economic development in general. * Contact: Karen Clay, Associate Professor of Economics and Public Policy, Carnegie Mellon University, Heinz College, 5000 Forbes Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213. Email: [email protected] † Contact: Ethan Schmick, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Economics, 4901 Wesley W. -

Public Health Reports

PUBLIC HEALTH REPORTS VOL 42 SEPTEMBER 30, 1927 NO. 39 POLIOMYELITIS IN THE UNITED STATES In June, 1927, reports from California showed more than the usual seasonal rise in the number of cases of poliomyelitis. Early in July a number of cases of this disease were reported in New Mexico. Later, other States reported local epidemics or a general increased prevalence of the disease. Illinois, Ohio, Massachusetts, Penn- sylvania, and New York City are among the other localities most affected. A comparison of the weekly telegraphic reports from States for the 10 weeks ended September 10, 1927, with the corresponding re- ports for the years 1925 and 1926 shows that the total nuimber of cases reported for the period in 1927 was almost the same as the number for the corresponding period in 1925, but the figures were nearly three times those for the same period of 1926. Reports for the week ended September 17, 1927, however, show about five times as many cases as for the corresponding period of 1926 and some- what more than twice as many as in 1925. The following are among the States reporting an increase in the number of cases for the week ended September 24, 1927: Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Michigan, Mis- souri, and Texas. Among the States showing a decrease in the number of cases for the week are California, Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. The telegraphic reports from States for the week ended September 24 will be found on page 2402. A STUDY OF THE PELLAGRA-PREVENTIVE ACTION OF THE COWPEA (VIGNA SINENSIS) AND OF COMMERCIAL WHEAT GERM By JOSEPH GOLDBERGER and G. -

Southern Jewish History

SOUTHERN JEWISH HISTORY Journal of the Southern Jewish Historical Society Mark K. Bauman, Editor Rachel B. Heimovics, Managing Editor Eric L. Goldstein, Book Review Editor 2 0 0 4 Volume 7 Southern Jewish History Mark K. Bauman, Editor Rachel B. Heimovics, Managing Editor Eric L. Goldstein, Book Review Editor Editorial Board Elliott Ashkenazi Martin Perlmutter Canter Brown, Jr. Marc Lee Raphael Eric Goldstein Stuart Rockoff Cheryl Greenberg Bryan Stone Scott Langston Clive Webb Phyllis Leffler George Wilkes Southern Jewish History is a publication of the Southern Jewish Historical Society and is available by subscription and as a benefit of membership in the Society. The opinions and statements expressed by contributors are not neces- sarily those of the journal or of the Southern Jewish Historical Society. Southern Jewish Historical Society OFFICERS: Minette Cooper, President; Sumner Levine, President-Elect; Scott M. Langston, Secretary; Bernard Wax, Treas- urer. BOARD OF TRUSTEES: Eric L. Goldstein, Irwin Lachoff, Phyllis Leffler, Stuart Rockoff, Robert N. Rosen, Betsy Blumberg Teplis. EX-OFFICIO: Hollace Ava Weiner, Jay Tanenbaum. Correspondence concerning author’s guidelines, contributions, and all edi- torial matters should be addressed to the Editor, Southern Jewish History, 2517 Hartford Dr., Ellenwood, GA 30294; email: [email protected]. The journal is interested in unpublished articles pertaining to the Jewish experience in the American South. For journal subscriptions and advertising, write Rachel B. Heimovics, SJH managing editor, 954 Stonewood Lane, Maitland, FL 32751; email: [email protected]; or visit www.jewishsouth.org. Articles appearing in Southern Jewish History are abstracted and/or indexed in Historical Abstracts, America: History and Life, Index to Jewish Periodicals, Journal of American History, and Journal of Southern History. -

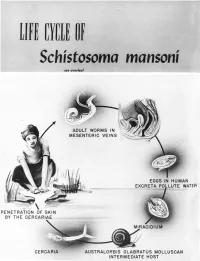

Ti-T&-INTERMEDIATE MOST

. .O .. PENETRATION OF SKIN a : BY THE GERtCARlAES::+i-:+. +40; CER CSTRALORBIS GLABR-ATUS MOLLUSCAN --ti-t&-INTERMEDIATE MOST Schistosomiasis The parasitic worms whlich cause schistosomiasis, a chronic disease pres- ent in about 114 million individuals throughout the world, follow a complex life cycle, illustrated on the frontispiece. The disease is particularly wide- spread in areas of the world with low standards of sanitation. In some areas of Egypt, for example, 90 percent of the population suffers from schistosomiasis, and the productive potential of the nation is estimated to be lowered one-third. The worms responsible for the disease are commonly known as blood flukes. They inhabit veins of the abdominal cavity and pelvis. The eggs extruded by the female worms penetrate various tissues and may find their way to all or nearly all organs of the body, where they cause inflammatory reactions and interfere with normal body function. Various attempts to control schistosomiasis have included improved sani- tation, mass chemotherapy, and attack on the snail intermediate hosts. The latter measure is one of the most promising, and in recent years attention has been focused on new chemicals which might be more effective. In many areas, transmission of the disease is intimately linked with age-old agri- cultural and religious practices, which are difficult to change. This, plus the factthat there is no satisfactory treatment for the disease, points to control of the snail hosts as one of the most promising approaches to the problem. A debilitating affliction which often makes its victims too sick or too weak to work, schistosomiasis runs a chronic course which may extend over many years. -

1 Introduction to Epidemiology

1: Introduction to Epidemiology DRAFT 1 Introduction to Epidemiology 1.1 Epidemiology And Its Uses • What is Epidemiology? • Unit of Concern • What is Public Health? • What is Health? • Other Useful Terms • Uses of Epidemiology 1.2 Evolving Patterns Of Morbidity And Mortality • Epidemiologic Transition and Demographic Transition • Mortality Trends Since 1950 • Trends in Life Expectancy 1.3 Historical Figures And Events • Roots of Epidemiology • John Graunt • Germ Theory • Médecine d’observation • The London Epidemiological Society • William Farr • John Snow • Twentieth-Century Epidemiology • Emile Durkheim • Joseph Goldberger • The British Doctors Study 1.1 EPIDEMIOLOGY AND ITS USES What Is Epidemiology? The word epidemiology is based on the Greek roots epi (upon), demos (the people, as in “democracy” and “demography”), and logia (“speaking of,” “the study of”). Specific use of the term epidemiology in the English language dates to around the time the London Epidemiological Society was established in the mid-19th century. Since then, epidemiology has been defined in many ways, including • the study of the distribution and determinants of diseases and injuries in populations (Mausner & Baum, 1974) • the study of the occurrence of illness (Gaylord Anderson cited in Cole, 1979, p. 15) © B. Burt Gerstman Page 1 Last printed 8/22/2011 3:43:00 PM 1: Introduction to Epidemiology DRAFT • a method of reasoning about disease that deals with biological inferences derived from observations of disease phenomena in population groups (Lilienfeld, 1978b, p. 89) • the quantitative analysis of the circumstances under which disease processes, including trauma, occur in population groups, and factors affecting their incidence, distribution, and host responses, and the use of this knowledge in prevention and control” (Evans, 1979, p. -

In the Early Half of the Twentieth Century a Mysterious Disease, “The Sharecropper's Plague”, Reached Epidemic Proportions

Profiles in Medical Courage: Joseph Goldberger, the Sharecropper’s Plague, Science and Prejudice “You must accept the truth from whatever source it comes”. -Maimonides The Sharecropper’s Plague In the early half of the twentieth century a mysterious disease, “the sharecropper’s plague”, reached epidemic proportions in the Southern US (1). Each state decided whether it would recognize and publicly admit the existence of what was then considered an embarrassment. The total number of new annual cases was estimated as about 75,000 in 1915 and about 100,000 throughout the 1920s (2). The disease had a 40% mortality rate, and many survivors with dementia were confined to mental institutions (3). Patients initially presented with symmetrically reddened skin, similar to that produced by a sunburn or poison oak. Later, the dermatitis turned rough and scaly in one or more locations, such as the hands, the tops of the feet, or the ankles, or in a butterfly-shaped distribution across the nose. Disturbances of the digestive tract and the nervous system occurred as late manifestations. This led to the plague being characterized by 4 D’s: dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia and death. In case you have not guessed, the “sharecropper’s plague” was pellagra. “Pellagraphobia" developed as the disease acquired a social stigma that left victims and their families ostracized (4). Many hospitals refused admittance to patients with pellagra and many staff refused to care for them. Quarantine was common and elementary schools tried to bar children whose family members had pellagra (5). The cause of the disease was unknown. A number of etiologies were proposed including infection; the eating of moldy corn; inherited susceptibility; heavy exposure to sunlight; and exposure to cottonseed oil (2).