Situating Gangs Within Scotland's Illegal Drugs Market(S)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lyons Family Group

THE LYONS FAMILY Assem bled by CHARLTON HAVARD LYONS for His Grandchildren This Genealogy is based on data from Dr. G. M. G. Stafford's: GENERAL LEROY AUGUSTUS STAFFORD, A GENEALOGY, and Annie Elizabeth Miller's: OUR FAMILY CIRCLE, and from members of the family and other sources. Letters from Dr. G. M. G. Stafford to C. H. Lyons 1165 Stanford Avenue Baton Rouge, Louisiana June 10, 1948 "My dear Charlton: "Many thanks for your recent letters relative to my genealogical efforts. We old fellows do not get many tokens of commendation especially where our 'hobbies' are concerned, such as your letter expressed, but they are al- ways gratefully received and are very soothing to our pride. We are told that pride was the cause of the fall of Lucifer and his fellow angels, so it is not a new essence in the makeup of God's creatures, and therefore we should not be held too culpable in still retaining a little of it. I have certainly en- joyed my genealogical work. It has been a great source of pleasure to me through these years of my retirement. Always being of an active tempera- ment I just had to have an outlet to a naturally restless disposition, and genealogy, in which I was always interested, came as a great solace to me. "We have a fine lot of forebears, from those uncompromising old Puri- tans of New England to those hot-blooded Southerners of Virginia and South Carolina. When old Grandpa Wright came to the 'Deep South' and married a girl whose progenitors had never been farther north than South Carolina, he mingled two strains of very different elements, and we are the result- and according to my way of thinking, not too bad a sample of good Americanism. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk i UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES School of History The Wydeviles 1066-1503 A Re-assessment by Lynda J. Pidgeon Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 15 December 2011 ii iii ABSTRACT Who were the Wydeviles? The family arrived with the Conqueror in 1066. As followers in the Conqueror’s army the Wydeviles rose through service with the Mowbray family. If we accept the definition given by Crouch and Turner for a brief period of time the Wydeviles qualified as barons in the twelfth century. This position was not maintained. By the thirteenth century the family had split into two distinct branches. The senior line settled in Yorkshire while the junior branch settled in Northamptonshire. The junior branch of the family gradually rose to prominence in the county through service as escheator, sheriff and knight of the shire. -

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Lyons Ranches Historic District, Redwood National Park

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2004 Lyons Ranches Historic District Redwood National Park Cultural Landscape Inventory: Lyons Ranches Historic District Redwood National Park Redwood National Park concurs with the finclings, including the Management Category and Condition Assessment assigned through completion of this Cultural Landscape Inventory for the Lyons Ranches Historic District as listed below: MANAGEMENT CATEGORY B: Should be preserved and maintained CONDITION ASSESSMENT: Fair Superintendent, ~edwoodNational Park Date Please return this form to: Shaun Provencher PWR CLI Coordinator National Park Service I 7 7 I Jackson Street, Suite 700 Oakland, CA 94607 LYONS RANCHES HISTORIC DISTRICT REDWOOD NATIONAL PARK California SHPO Eligibility Determination Section 110 Actions Requested: 1) SHPO concurrence with Determination of Eligibility (DOE) of the proposed Lyons Ranches Historic District for listing on the National Register, 2) SHPO concurrence with the addition of structures to the List of Classified Structures (LCS). (See chart below). x-I concur, Additional information is needed to concur, I do not concur with the proposed Lyons Ranches Historic District eligibility for listing (DOE) on the National Register of Historic Places. * See attached comments below. x- I concur, Additional information is needed to concur, I do not concur that the Setting as described in the CLI contributes to the historic district (see the following landscape characteristics: natural systems and features, spatial organization, cluster -

Vertical File

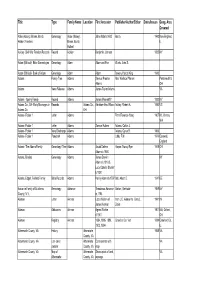

Title Type Family Name Location First Ancestor Publisher/Author/Editor Dates/Issues Geog. Area Covered Abbe (Abbey), Brown, Burch, Genealogy Abbe (Abbey), John Abbe b.1613 Burch 1943 New England, Hulbert Families Brown, Burch, IL Hulbert Ackley- Civil War Pension Records Record Ackley Benjamin Johnson 1832 NY Adam (Biblical)- Bible Genealogies Genealogy Adam Adam and Eve Wurts, John S. Adam (Biblical)- Book of Adam Genealogy Adam Adam Bowen, Harold King 1943 Adams Family Tree Adams Samuel Preston Mrs. Wallace Phorsm Portsmouth & Adams OH Adams News Release Adams James Taylor Adams VA Adams - Spring Family Record Adams James Wamorth? 1832 NY Adams Co., OH- Early Marriages in Records Adams Co., Abraham thru Wilson Ackley, Robert A. 1982 US Adams Co. OH Adams- Folder 1 Letter Adams From Florence Hoag 1907 Mt. Vernon, WA Adams- Folder 1 Letter Adams Samuel Adams Adams, Calvin J. Adams- Folder 1 Navy Discharge Adams Adams, Cyrus B. 1866 Adams- Folder 1 Pamphlet Adams Lobb, F.M. 1979 Cornwall, England Adams- The Adams Family Genealogy/ Tree Adams Jacob Delmar Harper, Nancy Eyer 1978 OH Adams b.1858 Adams, Broyles Genealogy Adams James Darwin KY Adams b.1818 & Lucy Ophelia Snyder b.1820 Adams, Edgell, Twiford Family Bible Records Adams Henry Adams b.1797 Bell, Albert D. 1947 DE Adriance Family of Dutchess Genealogy Adriance Theodorus Adriance Barber, Gertrude 1959 NY County, N.Y. m.1783 Aikman Letter Aikman Lists children of from L.C. Aikman to Cora L. 1941 IN James Aikman Davis Aikman Obituaries Aikman Agnes Ritchie 1901 MA, Oxford, d.1901 OH Aikman Registry Aikman 1884, 1895, 1896, Crawford Co. -

From Clan Forsyth Society

FORSYTH NOTES February 1, 2015 Welcome to the three hundredth seventh issue of Forsyth Notes. Forsyth Notes is published monthly by Clan Forsyth Society of the USA, and is your e-link to your extended Forsyth family. Click here for back issues of Forsyth Notes in PDF format. From Clan Forsyth Society A Wee Bit of Scottish Humor The Bagpiper By Gary Martz Time is like a river. You cannot touch the water twice, because the flow that has passed will never pass again. Enjoy every moment of life. As a bagpiper, I play many gigs. Recently I was asked by a funeral director to play at a graveside service for a homeless man. He had no family or friends, so the service was to be at a pauper's cemetery in the Nova Scotia back country. As I was not familiar with the backwoods, I got lost and, being a typical man, I didn't stop to ask for directions. I finally arrived an hour late and saw the funeral guy had evidently gone and the hearse was nowhere in sight. There were only the diggers and crew left and they were eating lunch. I felt badly and apologized to the men for being late. I went to the side of the grave and looked down and saw that the vault lid was already in place. I didn't know what else to do, so I started to play. The workers put down their lunches and began to gather around. I played out my heart and soul for this man with no family and friends. -

At Big Bear Brewing Company Our Story

AT BIG BEAR BREWING COMPANY We provide outstanding service and the highest quality food. We are committed to sourcing the highest quality ingredients at the peak of their season. Our soups, salad dressings, desserts, and sauces are homemade from scratch daily. We use locally sourced fresh seafood & produce. OUR STORY... Big Bear Brewing Co. opened its doors in July of 1997. Our concept was based on serving fresh brewed beer with quality and creative food in a warm and friendly atmosphere. When we opened, brewpubs were expanding throughout the country. Since then, the brewpub concept has slowed, but not Big Bear. We like to think of our very loyal guests as family, and after 21 years that family continues to grow. We have a strong foundation in this community and are very proud of that achievement. Behind the scenes of any successful restaurant is a devoted staff... we have many who have been with us since the beginning. Consistency breeds success and for that we thank our crew. A BRIEF HISTORY OF CORAL SPRINGS, FLORIDA A gentleman by the name Henry “Bud” Lyons obtained a vast amount of land between 1911 and 1939 that totaled over 20,000 acres. Although the land consisted of marshy wilderness, Lyons teamed with workers from the Bahamas, cleared and drained the land and used it to grow beans. This earned Lyons the nickname “Titan of the Bean Patch.” In 1952, Lyons passed away and left his large land holdings to his family. Lyon’s family brought in a head of 5,000 cattle and converted the land to be used for ranching. -

Dr. Thomas Pearse Lyons Is an Irish Entrepreneur Whose Vision for Improving Global Agriculture Has Built a Multibillion-Dollar International Business

Dr. Thomas Pearse Lyons is an Irish entrepreneur whose vision for improving global agriculture has built a multibillion-dollar international business. In the late 1970s, Lyons immigrated to the United States with his young family and a dream. His vision — to sustain the planet and all things living in it by finding ways to apply his yeast fermentation expertise to agricultural challenges — came to life in his home garage with $10,000. Today, that vision is put to work by Alltech’s global team of more than 5,000 people around the world. Alltech focuses on improving animal, crop and human health and performance through its innovative use of yeast fermentation, enzyme technology, algae and nutrigenomics. Its mission has always been guided by Dr. Lyons’ early commitment to the “ACE principle” – a promise that the company’s work must have a positive impact on the Animal, the Consumer and the Environment. Dr. Lyons is first and foremost an entrepreneur and tireless innovator, with a keen scientific mind. His scientific expertise, combined with an acute business sense, has helped revolutionize the animal feed industry through the introduction of natural ingredients to animal feed. He is widely regarded as an inspirational leader and communicator. He lives with passion and purpose — rising before dawn to begin communicating with colleagues around the world, issuing daily “One Minute Charge” motivational messages and traveling incessantly to meet his team members and customers in person. He has built Alltech into the fastest-growing company in the global animal health and nutrition industry through innovative technology and strong branding. -

Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution Through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M. Stampp Series I Selections from the Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Libraries Part 4: Barrow, Bisland, Bowman, and Other Collections Associate Editor and Guide Compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of ante-bellum southern plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin Schipper. Contents: ser. A. Selections from the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina (2 pts.)—[etc.]—ser. I. Selections from the Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Libraries—[etc.]—ser. M. Selections from the Virginia Historical Society. 1. Southern States—History—1775–1865—Sources. 2. Slave records—Southern States. 3. Plantation owners—Southern States—Archives. 4. Southern States— Genealogy. 5. Plantation life—Southern States— History—19th century—Sources. I. Stampp, Kenneth M. (Kenneth Milton) II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Schipper, Martin Paul. IV. South Caroliniana Library. V. South Carolina Historical Society. VI. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. VII. Maryland Historical Society. [F213] 975 86-892341 ISBN 1-55655-646-2 (microfilm : ser. I, pt. 4) Compilation © 1997 -

Southern Women and Their Families in the 19Th Century

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Research Collections in Women’s Studies General Editors: Anne Firor Scott and William H. Chafe Southern Women and Their Families in the 19th Century: Papers and Diaries Consulting Editor: Anne Firor Scott Series C, Holdings of The Earl Gregg Swem Library, The College of William and Mary in Virginia: Miscellaneous Collections, 1773–1938 Associate Editor and Guide Compiled by Martin P. Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Southern women and their families in the 19th century, papers and diaries. Series C, Holdings of the Earl Gregg Swem Library, the College of William and Mary in Virginia, miscellaneous collections, 1773–1938 [microform] / consulting editor, Anne Firor Scott, microfilm reels. — (Research collections in women’s studies) Accompanied by printed guide, compiled by Martin P. Schipper, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Southern women and their families in the 19th century, papers and diaries. Series C, Holdings of the Earl Gregg Swem Library, the College of William and Mary in Virginia, miscellaneous collections, 1773–1938. ISBN 1-55655-499-0 (microfilm) 1. Women—Virginia—History—19th century—Sources. 2. Family— Virginia—History—19th Century—Sources. I. Scott, Anne Firor, 1921– . II. Schipper, Martin Paul. III. College of William and Mary. Swem Library. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) V. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Southern women and their families in the 19th century, papers and diaries. Series C, Holdings of the Earl Gregg Swem Library, the College of William and Mary in Virginia, miscellaneous collections, 1773–1938. -

Family Tree Maker

The Lyons Family by Lori Lyons Table of Contents Outline Descendant Tree of Roger de Leonne.......................................................................................................2 Notes for Roger de Leonne..................................................................................................................................13 Family Group Sheet.............................................................................................................................................15 Family Group Sheet.............................................................................................................................................20 Family Group Sheet.............................................................................................................................................22 Descendant Tree of Joseph Lucius Cincinatus Pitt Lyon.....................................................................................26 Index....................................................................................................................................................................33 1 The Lyons Family Descendants of Roger de Leonne 1 Roger de Leonne 1040 - .. 2 Paganus de Leonibus 1080 - ....... 3 Hugh de Leonibus 1120 - 1175 ............ 4 Ernald de Leonibus 1150 - 1199 ................. 5 John Lyon 1175 - 1226 ...................... 6 Pagan de Leonibus 1200 - ............................ +Ivette de Ferrers ........................... 7 John de Lyoun 1225 - ................................ -

The Family Bible Preservation Project Has Compiled a List of Family Bible Records Associated with Persons by the Following Surname

The Family Bible Preservation Project's - Family Bible Surname Index - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Page Forward to see each Bible entry THE FAMILY BIBLE PRESERVATION PROJECT HAS COMPILED A LIST OF FAMILY BIBLE RECORDS ASSOCIATED WITH PERSONS BY THE FOLLOWING SURNAME: LYONS Scroll Forward, page by page, to review each bible below. Also be sure and see the very last page to see other possible sources. For more information about the Project contact: EMAIL: [email protected] Or please visit the following web site: LINK: THE FAMILY BIBLE INDEX Copyright - The Family Bible Preservation Project The Family Bible Preservation Project's - Family Bible Surname Index - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Page Forward to see each Bible entry SURNAME: LYONS UNDER THIS SURNAME - A FAMILY BIBLE RECORD EXISTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE FOLLOWING FAMILY/PERSON: FAMILY OF: LYONS, ABRAHAM (1783-1853) SPOUSE: MARY ANN MORE INFORMATION CAN BE FOUND IN RELATION TO THIS BIBLE - AT THE FOLLOWING SOURCE: SOURCE: ONLINE INDEX: D.A.R. BIBLE RECORD DATABASE FILE/RECD: BIBLE DESCRIPTION: ABRAHAM LYONS (1783-1853) AND WIFE, MARY ANN (1787-1856) NOTE: - BOOK TITLE: KENTUCKY DAR GRC REPORT ; S1 V286 : BIBLE, CEMETERY AND MARRIAGE RECORDS FROM LOGAN, BOONE, PIKE, GRANT, DAVIESS COS THE FOLLOWING INTERNET HYPERLINKS CAN BE HELPFUL IN FINDING MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THIS FAMILY BIBLE: LINK: CLICK HERE TO ACCESS LINK LINK: CLICK HERE TO ACCESS LINK GROUP CODE: 02 Copyright - The Family Bible Preservation Project The Family Bible Preservation Project's - Family Bible Surname Index - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Page Forward to see each Bible entry SURNAME: LYONS UNDER THIS SURNAME - A FAMILY BIBLE RECORD EXISTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE FOLLOWING FAMILY/PERSON: FAMILY OF: LYONS, ABSALOM (XXXX-XXXX) SPOUSE: SUSANNAH SHEAR MORE INFORMATION CAN BE FOUND IN RELATION TO THIS BIBLE - AT THE FOLLOWING SOURCE: SOURCE: ONLINE INDEX: D.A.R. -

Eugene Lyons Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8h4nb2xg No online items Register of the Eugene Lyons papers Finding aid prepared by Ronald Bulatoff Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1998 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Eugene Lyons 85006 1 papers Title: Eugene Lyons papers Date (inclusive): 1919-1981 Collection Number: 85006 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 17 manuscript boxes, 3 oversize boxes, 10 envelopes, 1 album box, 6 phonotapes, 13 phonorecords(10.0 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, writings, notes, pamphlets, other printed matter, photographs, and sound recordings, relating primarily to conditions in the Soviet Union under communism, the international communist movement, and the career of Herbert Hoover. Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives Acquisition Information Materials were acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1985. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Eugene Lyons papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. 1898, July 1 Born, Uzlian, Russia 1907 Arrived in the United States 1917-18 Student, College City of New York 1918 Private, U.S. Army 1918-19 Student, Columbia