The Continuing Evolution of Proxy Representation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Shrinking Scope of CSR in UK Corporate Law, 74 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 74 | Issue 2 Article 16 4-1-2017 The hrS inking Scope of CSR in UK Corporate Law Andrew Johnston School of Law, University of Sheffield Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew Johnston, The Shrinking Scope of CSR in UK Corporate Law, 74 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1001 (2017), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol74/iss2/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Shrinking Scope of CSR in UK Corporate Law Andrew Johnston* Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................... 1002 II. The Law Before 1948 ..................................................... 1007 III. The Company Law Reforms of 1948 .............................. 1013 IV. 1970s Industrial Democracy Reforms ........................... 1018 V. The 2006 Reforms .......................................................... 1028 VI. Conclusion: The Prospects for CSR ............................... 1036 Abstract Through a historical analysis of corporate law reforms in the United Kingdom (UK) during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, this paper traces the shrinking scope for corporations to take socially responsible decisions. It offers a detailed examination of the rationales and drivers of the reforms, and shows that, by focusing exclusively on the question of accountability of directors to shareholders, wider social concerns were “bracketed” after 1948, leading to a permanent state of “crisis,” which constantly threatens the legitimacy of the corporate law system. -

Companies Act 2006

c i e AT 13 of 2006 COMPANIES ACT 2006 Companies Act 2006 Index c i e COMPANIES ACT 2006 Index Section Page PART I – INCORPORATION AND STATUS OF COMPANIES 11 CHAPTER 1 - INCORPORATION 11 1 Types of company ......................................................................................................... 11 2 Application to incorporate a company ...................................................................... 11 3 Incorporation of a company ........................................................................................ 12 4 Subscribers become members of the company on incorporation .......................... 12 CHAPTER 2 - MEMORANDUM AND ARTICLES 12 5 Memorandum................................................................................................................ 12 6 Power to prescribe model articles .............................................................................. 13 7 Effect of memorandum and articles ........................................................................... 14 8 Amendment of memorandum and articles ............................................................... 14 9 Filing of notice of amendment of memorandum or articles ................................... 15 10 Provision of copies of memorandum and articles to members .............................. 15 CHAPTER 3 - COMPANY NAMES 15 11 Required part of company name ................................................................................ 15 12 Requirement for name approval ............................................................................... -

Taking Stock of the Companies Act 2006 Deirdre Ahern*

Statute Law Review Advance Access published January 4, 2014 Statute Law Review, 2013, Vol. 00, No. 00, 1–14 doi:10.1093/slr/hmt026 Codification of Company Law: Taking Stock of the Companies Act 2006 Deirdre Ahern* ABSTRACT The Companies Act 2006 was presented by the Labour Government of the day as a Downloaded from tour de force in legislative drafting, pursuing a multi-faceted policy agenda designed to appeal to a range of stakeholders. This article considers the lengthy review process which led to the drafting and enactment of the Companies Act 2006 including the underlying work of the Company Law Review and the English and Scottish Law Commissions which laid the groundwork for the drafting of the Act. The Act is evaluated at a macro-level from http://slr.oxfordjournals.org/ the perspective of its avowed objectives as both a codifying and reforming Act and one which was designed to advance a pro-enterprise mandate. The article also examines the plain language agenda which was designed to make company law more accessible, as well as how the transfer of the common law and equitable duties of directors to statute was handled at drafting stage. In this regard, subsections 170(3) and (4) of the Companies Act 2006 contain a unique set of instructions in relation to the replacement of the duties albeit with a dissonant instruction to interpret the new statutory duties with regard to the rules and principles they replace, something which proved controversial during the Parliamentary process. The manner in which the courts in the intervening years have by guest on August 15, 2014 approached the interpretation of these statutory duties is therefore examined. -

Corporate Membership in Early UK Company Law

This is a repository copy of A tale of unintended consequence: corporate membership in early UK company law. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/125325/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Mackie, C orcid.org/0000-0002-8560-2427 (2017) A tale of unintended consequence: corporate membership in early UK company law. Journal of Corporate Law Studies, 17 (1). pp. 1-37. ISSN 1473-5970 https://doi.org/10.1080/14735970.2016.1209803 © 2016 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Journal of Corporate Law Studies on 23 August 2016, available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/14735970.2016.1209803 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ A TALE OF UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCE: CORPORATE MEMBERSHIP IN EARLY UK COMPANY LAW COLIN MACKIE* ABSTRACT. This article seeks to elucidate the historical basis in UK company law of the right for one company to be a member (i.e. -

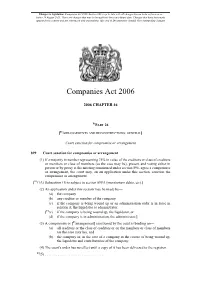

Companies Act 2006, Section 899 Is up to Date with All Changes Known to Be in Force on Or Before 19 August 2021

Changes to legislation: Companies Act 2006, Section 899 is up to date with all changes known to be in force on or before 19 August 2021. There are changes that may be brought into force at a future date. Changes that have been made appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Companies Act 2006 2006 CHAPTER 46 F1 PART 26 [F1ARRANGEMENTS AND RECONSTRUCTIONS: GENERAL] Court sanction for compromise or arrangement 899 Court sanction for compromise or arrangement (1) If a majority in number representing 75% in value of the creditors or class of creditors or members or class of members (as the case may be), present and voting either in person or by proxy at the meeting summoned under section 896, agree a compromise or arrangement, the court may, on an application under this section, sanction the compromise or arrangement. [F1(1A) Subsection (1) is subject to section 899A (moratorium debts, etc).] (2) An application under this section may be made by— (a) the company, (b) any creditor or member of the company, (c) if the company is being wound up or an administration order is in force in relation it, the liquidator or administrator. [F2(c) if the company is being wound up, the liquidator, or (d) if the company is in administration, the administrator.] (3) A compromise or [F3arrangement] sanctioned by the court is binding on— (a) all creditors or the class of creditors or on the members or class of members (as the case may be), and (b) the company or, in the case of a company in the course of being wound up, the liquidator and contributories of the company. -

Company Law I 2008 - 2009

1 COMPANY LAW I 2008 - 2009 SEMESTER ONE - LECTURE OUTLINE I AN OVERVIEW OF OUR COMPANY LAW COURSE Semester One: . Choice of Business Organisation & Company Registration . Separate Corporate Legal Personality . Corporate Governance: Distribution of power between board of directors and shareholders’ general meeting and executives and non executive directors . Directors’ Duties . Minority Shareholder Protection Semester Two . Agency and Company Capacity: Who can bind the Company to a Contract, or make it liable in Tort or Criminal Law? . Capital – shares, loans, and markets in shares. Take-overs and Mergers of PLC’s . Insolvency and Dissolution of Companies: especially liability of directors. Choice of Business Structure Aim: o To set the context and help you to understand the key features of the main structures and issues in choosing between business structures. Reading: Davies and Gower, Chapters 1 & 2 Hicks and Goo 6th edition pp 33-77 gives an idea of the development of a business – especially the story on pages 33-40. Pages 41-77 provide the relevant documents for the company in the story. Pages 91-94 outline some of the choices for those setting up a small business. See G. Morse, Partnership Law (Blackstone) 6th Edition (2006) chapters 1 and 9 for a little more detail on partnerships. Blackett Ord Partnership, Butterworths, 2002 Chapter 1 pp 1-5; Chap 2 pp 10-34 & Chapter 10, 11, 16, 20 & 21 is good for reference or if you are particularly interested in going more deeply into partnership law. NOTE: Companies Act 2006 changes the documentation of company constitutions. It makes the Memorandum of Association a document with few details in it which is lodged when the company is registered. -

Unfair Prejudice Petitions- Lessons to Be Learnt and Recent Development

UNFAIR PREJUDICE PETITIONS – LESSONS TO BE LEARNT AND RECENT DEVELOPMENTS When entering into a corporate relationship, few contemplate an If unavoidable, you may need to consider making them a fair acrimonious split some years down the line. Even with carefully offer for their shares. documented agreements, including exit provisions, relationships Valuation: Unfair prejudice disputes are costly, time can turn sour and expectations may not be met. Whether a majority consuming and often involve “airing dirty laundry in public”. As or a minority investor, it is important to understand the remedy of the petitioner’s goal is likely to be a share buyout, consider unfair prejudice both to ensure you can best guard against it and whether it is possible to value the shares and make an early utilise it should the need arise. offer to buy the minority’s shares. This will involve seeking early expert advice on the value of the shares. Whilst there are a number of causes of action for aggrieved shareholders, we are seeing an increased use of the statutory Resolution: A straightforward valuation of the petitioner’s protection afforded for unfair prejudice, notwithstanding it being an shares might give rise to difficulty. There may be other issues expensive and fraught process. This is often a process called upon that need to be determined first before a valuation can be to bring the relationship to an end but is equally an effective tool carried out, such as what adjustments should be made to to take control of a company or ensure that conduct is regulated reflect any breaches of duty by the majority shareholders. -

The Companies Act 1985 and the Companies Act 2006 ______

THE COMPANIES ACT 1985 AND THE COMPANIES ACT 2006 __________ A COMPANY LIMITED BY GUARANTEE AND NOT HAVING A SHARE CAPITAL __________ ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION OF CAMBRIDGE WIRELESS LIMITED ___________ PRELIMINARY 1. The regulations contained in Table A in the Schedule to the Companies (Tables A to F) Regulations 1985 as amended by the Companies (Tables A to F) (Amendment) Regulations 1985, the Companies Act 1985 (Electronic Communications) Order 2000, the Companies (Tables A to F) (Amendment) Regulations 2007 and the Companies (Tables A to F) (Amendment) (No. 2) Regulations 2007 do not apply to the company. 2. In these articles — “the Act” means the Companies Act 1985 including any statutory modification or re- enactment thereof for the time being in force and any provisions of the Companies Act 2006 for the time being in force. “the articles” means the articles of the company. "the Company" means Cambridge Wireless Limited. “clear days” in relation to the period of a notice means that period excluding the day when the notice is given or deemed to be given and the day for which it is given or on which it is to take effect. "communication" means the same as in the Electronic Communications Act 2000. "electronic communication" means the same as in the Electronic Communications Act 2000. “executed” includes any mode of execution. "guarantor" means those individuals, companies or organisations that have agreed in writing to contribute £1 towards the liabilities of the company. “office” means the registered office of the company. “secretary” means the secretary of the company or any other person appointed to perform the duties of the secretary of the company, including a joint, assistant or deputy secretary. -

The Development of English Company Law Before 1900

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Turner, John D. Working Paper The development of English company law before 1900 QUCEH Working Paper Series, No. 2017-01 Provided in Cooperation with: Queen's University Centre for Economic History (QUCEH), Queen's University Belfast Suggested Citation: Turner, John D. (2017) : The development of English company law before 1900, QUCEH Working Paper Series, No. 2017-01, Queen's University Centre for Economic History (QUCEH), Belfast This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/149911 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu QUCEH WORKING PAPER SERIES http://www.quceh.org.uk/working-papers THE DEVELOPMENT OF ENGLISH COMPANY LAW BEFORE 1900 John D. -

Rise and Fall of the Ultra Vires Doctrine in United States, United Kingdom, and Commonwealth Caribbean Corporate Common Law: a Triumph of Experience Over Logic

DePaul Business and Commercial Law Journal Volume 5 Issue 1 Fall 2006 Article 4 Rise and Fall of the Ultra Vires Doctrine in United States, United Kingdom, and Commonwealth Caribbean Corporate Common Law: A Triumph of Experience Over Logic Stephen J. Leacock Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/bclj Recommended Citation Stephen J. Leacock, Rise and Fall of the Ultra Vires Doctrine in United States, United Kingdom, and Commonwealth Caribbean Corporate Common Law: A Triumph of Experience Over Logic, 5 DePaul Bus. & Com. L.J. 67 (2006) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/bclj/vol5/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Business and Commercial Law Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rise and Fall of the Ultra Vires Doctrine in United States, United Kingdom, and Commonwealth Caribbean Corporate Common Law: A Triumph of Experience Over Logic Stephen J.Leacock* "Pure logical thinking cannot yield us any knowledge of the empiri- cal world; all knowledge of reality starts from experience and ends in it."1 2 I. INTRODUCTION In free market3 economies, corporate laws change over time. More- over, experience has taught us that some legislative enactments, when * Professor of Law, Barry University School of Law. Barrister (Hons.) 1972, Middle Temple, London; LL.M. 1971, London University, King's College; M.A. (Bus. Law) CNAA 1971, City of London Polytechnic (now London Guildhall University), London; Grad. -

Ila Conference 2013 Eurosail on Trial – the Implications

ILA CONFERENCE 2013 EUROSAIL ON TRIAL – THE IMPLICATIONS David Chivers QC – Erskine Chambers Jeremy Goldring – South Square Chambers David Allison – South Square Chambers Introduction 1. The session will be spent exploring the arguments for and against the findings of the Court of Appeal in the Eurosail case, considering the wider implications of the decision, and discussing the possible approach of the Supreme Court on what represents the first opportunity for the highest court to consider the meaning of section 123 IA 1986 since its introduction onto the statute book more than 25 years ago. 2. This paper is intended to serve as an introduction to the issues that will be discussed during the session. It addresses the following topics: (1) section 123 IA 1986 and its statutory context; (2) the statutory history of section 123 IA 1986; (3) the facts of the Eurosail case; and (4) the findings of the Court of Appeal. (1) Section 123 IA 1986 3. Section 123 is one of the four main sections in Chapter VI of Part IV of the IA86, concerned with the grounds and effect of winding up petitions. 4. Section 122(1) is headed “Circumstances in which company may be wound up by the Court”. Sub-paragraphs (a) to (g) identify those circumstances. One of the circumstances in which a company may be wound up is that the company is unable to pay its debts. Section 122(1) provides (in so far as relevant) that: “A company may be wound up by the court if - … 1 (f) the company is unable to pay its debts,”. -

Bankruptcy Law Client Strategies in Europe

I N S I D E T H E M I N D S Bankruptcy Law Client Strategies in Europe Leading Lawyers on Analyzing the European Bankruptcy Process, Developing Creative Strategies for Clients, and Understanding the Latest Laws and Trends ©2010 Thomson Reuters/Aspatore All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the U.S. Copyright Act, without prior written permission of the publisher. This book is printed on acid free paper. Material in this book is for educational purposes only. This book is sold with the understanding that neither any of the authors nor the publisher is engaged in rendering legal, accounting, investment, or any other professional service. Neither the publisher nor the authors assume any liability for any errors or omissions or for how this book or its contents are used or interpreted or for any consequences resulting directly or indirectly from the use of this book. For legal advice or any other, please consult your personal lawyer or the appropriate professional. The views expressed by the individuals in this book (or the individuals on the cover) do not necessarily reflect the views shared by the companies they are employed by (or the companies mentioned in this book). The employment status and affiliations of authors with the companies referenced are subject to change. Aspatore books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use.