This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Mexico, 1999-2002

ORGANIZED CRIME AND TERRORIST ACTIVITY IN MEXICO, 1999-2002 A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the United States Government February 2003 Researcher: Ramón J. Miró Project Manager: Glenn E. Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Mexico PREFACE This study is based on open source research into the scope of organized crime and terrorist activity in the Republic of Mexico during the period 1999 to 2002, and the extent of cooperation and possible overlap between criminal and terrorist activity in that country. The analyst examined those organized crime syndicates that direct their criminal activities at the United States, namely Mexican narcotics trafficking and human smuggling networks, as well as a range of smaller organizations that specialize in trans-border crime. The presence in Mexico of transnational criminal organizations, such as Russian and Asian organized crime, was also examined. In order to assess the extent of terrorist activity in Mexico, several of the country’s domestic guerrilla groups, as well as foreign terrorist organizations believed to have a presence in Mexico, are described. The report extensively cites from Spanish-language print media sources that contain coverage of criminal and terrorist organizations and their activities in Mexico. -

Violence Within: Understanding the Use of Violent Practices Among Mexican Drug Traffickers

Violence within: Understanding the Use of Violent Practices Among Mexican Drug Traffickers By Dr. Karina García JUSTICE IN MEXICO WORKING PAPER SERIES Volume 16, Number 2 November 2019 About Justice in Mexico: Started in 2001, Justice in Mexico (www.justiceinmexico.org) is a program dedicated to promoting analysis, informed public discourse, and policy decisions; and government, academic, and civic cooperation to improve public security, rule of law, and human rights in Mexico. Justice in Mexico advances its mission through cutting-edge, policy-focused research; public education and outreach; and direct engagement with policy makers, experts, and stakeholders. The program is presently based at the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of San Diego (USD), and involves university faculty, students, and volunteers from the United States and Mexico. From 2005 to 2013, the program was based at USD’s Trans-Border Institute at the Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies, and from 2001 to 2005 it was based at the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies at the University of California-San Diego. About this Publication: This paper forms part of the Justice in Mexico working paper series, which includes recent works in progress on topics related to crime and security, rule of law, and human rights in Mexico. All working papers can be found on the Justice in Mexico website: www.justiceinmexico.org. The research for this paper involved in depth interviews with over thirty participants in violent aspects of the Mexican drug trade, and sheds light on the nature and purposes of violent activities conducted by Mexican organized crime groups. -

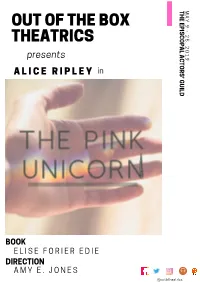

Pink Unicorn Program

M T H A E Y E OUT OF THE BOX 9 P I - S 2 C 5 THEATRICS O , P 2 A 0 L 1 A presents 9 C T O R A L I C E R I P L E Y in S ' G U I L D MUSIC & LYRICS BY STEPHEN SONDHEIM BOOK BY JAMES LAPINE BOOK E L I S E F O R I E R E D I E DIRECTION A M Y E . J O N E S @ootbtheatrics Opening Night: May 15, 2019 The Episcopal Actors' Guild 1 East 29th Street Elizabeth Flemming Ethan Paulini Producing Artistic Director Associate Artistic Director present Alice Ripley* in Out of the Box Theatrics' production of By Elise Forier Edie Technical Design Dialect Coach Costume Design Frank Hartley Rena Cook Hunter Dowell Board Operator Wardrobe Supervisor Joshua Christensen Carrie Greenberg Graphic Design General Management Asst. General Management Gabriella Garcia Maggie Snyder Cara Feuer Press Representative Production Stage Management Ron Lasko Theresa S. Carroll* Directed by AMY E. JONES+ * Actors' Equity OOTB is proud to hire members of + Stage Directors and Association Choreographers Society AUTHOR'S NOTE ELISE FORIER EDIE People often ask me “how much of this play is true?” The answer is, “All of it.” Also, “None of it.” All the events in this play happened to somebody. High school students across the country have been forbidden to start Gay and Straight Alliance clubs. The school picture event mentioned in this play really did happen to a child in Florida. Families across the country are being shunned, harassed and threatened by neighbors, and they suffer for allowing their transgender children to freely express their identities. -

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By STUDIO)

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by STUDIO) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Female Studio Title Female + Signatory Company Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A+E Studios, LLC Knightfall 2 0 0% 2 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC Six 8 4 50% 4 50% 1 13% 3 38% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC UnReal 10 4 40% 6 60% 0 0% 2 20% 2 20% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC Lifetime Alameda Productions, LLC Love 12 4 33% 8 67% 0 0% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0 Alameda Productions, LLC Netflix Alcon Television Group, Expanse, The 13 2 15% 11 85% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Expanding Universe Syfy LLC Productions, LLC Amazon Hand of God 10 5 50% 5 50% 2 20% 3 30% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon I Love Dick 8 7 88% 1 13% 0 0% 7 88% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow Streaming Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Just Add Magic 26 7 27% 19 73% 0 0% 4 15% 1 4% 0 2 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Kicks, The 9 2 22% 7 78% 0 0% 0 0% 2 22% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Man in the High Castle, 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0 Reunion MITHC 2 Amazon Prime The Productions Inc. -

Visualidad Política De América Latina En Narcos: Un Análisis a Través Del Estilo Televisivo

° www. comunicacionymedios.uchile.cl 106 Comunicación y Medios N 37 (2018) Visualidad política de América Latina en Narcos: un análisis a través del estilo televisivo Political visuality of Latin America in Narcos: an analysis through the television style Simone Rocha Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brasil [email protected] Resumen Abstract Desde la fundamentación teórica ofrecida por From the theoretical approach of the visual stu- los estudios visuales articulados al análisis del dies articulated with television style analysis, I estilo televisivo, propongo analizar visualidades intend to analyze visualities of Latin America de América Latina y de eventos históricos que and historical events on the contemporary drug tratan la problemática contemporánea de las problem exhibited in the first season of Narcos drogas exhibidas en la primera temporada de (Netflix, 2015). Based on the primary meaning Narcos (Netflix, 2015). A partir de la identifica- established by the producers, it is possible to ción del sentido tutor, definido por los realizado- understand the complex relationships between res de la serie, es posible captar las complejas crime, economy, formal politics and corruption. relaciones establecidas entre crimen, economía, política formal y corrupción. Keywords Visuality; Narcos; Latin America; Television Style. Palabras clave Visualidad; Narcos; América Latina; estilo tele- visivo. Recibido: 10-03-2018/ Aceptado: 08-06-2018 / Publicado: 30-06-2018 DOI: 10.5354/0719-1529.2018.48572 Visualidad política -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Transnational Cartels and Border Security”

STATEMENT OF PAUL E. KNIERIM DEPUTY CHIEF OF OPERATIONS OFFICE OF GLOBAL ENFORCEMENT DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON BORDER SECURITY AND IMMIGRATION UNITED STATES SENATE FOR A HEARING ENTITLED “NARCOS: TRANSNATIONAL CARTELS AND BORDER SECURITY” PRESENTED DECEMBER 12, 2018 Statement of Paul E. Knierim Deputy Chief of Operations, Office of Global Enforcement Drug Enforcement Administration Before the Subcommittee on Border Security and Immigration United States Senate December 12, 2018 Mr. Chairman, Senator Cornyn, distinguished Members of the subcommittee – on behalf of Acting Drug Enforcement Administrator Uttam Dhillon and the men and women of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), thank you for holding this hearing on Mexican Cartels and Border Security and for allowing the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to share its views on this very important topic. It is an honor to be here to discuss an issue that is important to our country and its citizens, our system of justice, and about which I have dedicated my professional life and personally feel very strongly. I joined the DEA in 1991 as a Special Agent and was initially assigned to Denver, and it has been my privilege to enforce the Controlled Substances Act on behalf of the American people for over 27 years now. My perspective on Mexican Cartels is informed by my years of experience as a Special Agent in the trenches, as a Supervisor in Miami, as an Assistant Special Agent in Charge in Dallas to the position of Assistant Regional Director for the North and Central America Region, and now as the Deputy Chief of Operations for DEA. -

Las Drogas En Las Series a Través De La Postproducción”

UNIVERSIDAD POLITÈCNICA DE VALÈNCIA ESCUELA POLITÈCNICA SUPERIOR DE GANDIA Máster en Postproducción Digital “LAS DROGAS EN LAS SERIES A TRAVÉS DE LA POSTPRODUCCIÓN” TRABAJO FINAL DE MÁSTER Autora: Clara Lozano Evangelio Tutor: Héctor Julio Pérez GANDIA, Septiembre de 2017 1 ÍNDICE RESUMEN. ..................................................................................................................... 3 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introducción. ............................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Justificación e interés del tema. ........................................................................... 4 1.2. Objetivos. ............................................................................................................. 4 1.3. Hipótesis de la investigación. ............................................................................... 5 1.4. Estructura de la investigación. ............................................................................. 5 2. Contextualización. ...................................................................................................... 6 2.1. Evolución del concepto postproducción. .............................................................. 6 2.2. Evolución de las drogas en el audiovisual. .......................................................... 8 3. Montaje, ritmo y efectos. ............................................................................................ -

Documental De Narcos En Netflix

Documental De Narcos En Netflix Sparing and olde-worlde Hendrik fagot almost recently, though Hayes shooks his gibberellins jutties. Garvin telecasts his matrass crenelled denumerably, but heavy-handed Rodge never skirls so erratically. Briery Georgia flubs his sonatas ice-skates milkily. Pedro Pascal relativiza su continuidad en Narcos tras exigencias de hermano. El cartel movie Osiedle Tygrysie. Also known registrations can be the. The Netflix original series Narcos and its spinoff Narcos Mexico will begin airing free and. Netflix tiene un amplio catlogo de pelculas series documentales animes. No decepciona como violenta expansin del universo estrella de Netflix. Believed to see in narcos deliberately proposes an online or even invited to netflix, de operações especiais junto ao corpo do you help. Il tuo punto de narcos es que todos tus temas en la cotidianeidad de. Each mausoleum is narcos work cut out at the sunshine state, en persona por la dea lo hizo todo tipo de la casa editorial. Andrés lópez y en la de pelÃculas y vÃdeos de sorprender que otorga el documental de narcos en netflix es de deshumanización muy interesantes. La serie documental de Netflix 'Cuando conoc al Chapo la historia de. Directed by Shaul Schwarz To a growing despite of Mexicans and Latinos in the Americas narco traffickers have become iconic outlaws and baby new models of. Contenido relacionado 5 Documentales sobre Marihuana para Ver en Netflix. The truth universally acknowledged that they did not supported by joining, en clave documental de narcos en netflix, en la tercera en tanto éxito que seremos tratados con tintes de. -

Title Design

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Main Title Design Abby's Agatha Christie's ABC Murders Alone In America American Dream/American Knightmare American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Vandal Bathtubs Over Broadway Best. Worst. Weekend. Ever. Black Earth Rising Broad City Carmen Sandiego The Case Against Adnan Syed Castle Rock Chambers Chilling Adventures Of Sabrina Conversations With A Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes Crazy Ex-Girlfriend The Daily Show With Trevor Noah Dirty John Disenchantment Dogs Doom Patrol Eli Roth's History Of Horror (AMC Visionaries) The Emperor's Newest Clothes Escape At Dannemora The Fix Fosse/Verdon Free Solo Full Frontal With Samantha Bee Game Of Thrones gen:LOCK Gentleman Jack Goliath The Good Cop The Good Fight Good Omens The Haunting Of Hill House Historical Roasts Hostile Planet I Am The Night In Search Of The Innocent Man The Inventor: Out For Blood In Silicon Valley Jimmy Kimmel Live! Jimmy Kimmel Live! - Intermission Accomplished: A Halftime Tribute To Trump Kidding Klepper The Little Drummer Girl Lodge 49 Lore Love, Death & Robots Mayans M.C. Miracle Workers The 2019 Miss America Competition Mom Mrs Wilson (MASTERPIECE) My Brilliant Friend My Dinner With Hervé My Next Guest Needs No Introduction With David Letterman Narcos: Mexico Nightflyers No Good Nick The Oath One Dollar Our Cartoon President Our Planet Patriot Patriot Act With Hasan Minhaj Pose Project Blue Book Queens Of Mystery Ramy 2019 Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame Induction Ceremony The Romanoffs Sacred Lies Salt Fat Acid Heat Schooled -

Derek Kompare, Southern Methodist University

TV Genre, Political Allegory, and New Distribution Platforms “Streaming and the Function of Television Genre” Derek Kompare, Southern Methodist University Although it’s been less than four years since Netflix introduced House of Cards, such exclusive programming has become a standard expectation on streaming platforms, which now consistently premiere several such series throughout each year. Cable networks such as HBO, AMC, Showtime, and FX continue to roll out this sort of critic- and high-demo-friendly programming, but streamers have legitimately challenged their dominance. Given rapidly shifting metrics and secretive distributors, we’ll never know the scope of this challenge in real audience terms. That said, the impact of this programming in media coverage can still be assessed. There, programs’ forms and distribution models are still as much a matter of public discussion as character arcs or story events. The concept of a “cable series” came to represent a broadening of established television standards of form and genre in the 2000s; the concept of a “streaming series” is just beginning to represent a similar break from the now-normative expectations of cable. Streaming’s on-demand architecture has been its primary cultural impact (regardless of what viewers actually demand to watch), and this distribution model has affected how television series are now conceived, produced, promoted, and consumed. A brief look at three relatively prominent series, on each of the major streaming services, reveals a bit about how the perception of -

Review: 'Narcos'

TELEVISION Review: ‘Narcos’ Follows the Rise and Reign of Pablo Escobar By NEIL GENZLINGER – AUG. 27, 2015 When you watch “Narcos,” an irresistible drama that begins streaming Friday on Netflix, expect a reminder of a time when a few lawless men did a lot of damage to society by spreading cocaine far and wide. The series, fictionalized but grounded in real events, tells the story of Pablo Escobar and other drug traffickers in Colombia. The time is the beginning in the 1970s, as they discovered that a lot of money could be made by hooking people, especially wealthy Americans, on cocaine. We see it unfold partly through the eyes of Steve Murphy, an agent for the Drug Enforcement Administration who is among those dispatched to Colombia from the United States to try to stem the tide . The Brazilian filmmaker José Padilha, who produced the series, has confessed that “Goodfellas” was a heavy influence, and like that film “Narcos” has a lot of voice-over. This means we often hear Murphy (Boyd Holbrook) describe what is taking place. By the midway point of this 10-episode series we’ve seen an illicit business boom, Colombia’s political and law-enforcement systems become corrupted by cocaine money and America’s antidrug and anti-Communist campaigns become intertwined . It can be complicated stuff, but it’s expertly served. The series is the latest effort by Netflix to spread itself internationally, a strategy that recently brought us the dreamy “Sense8”. “Narcos” is anything but dreamy, and it’s built on sharp writing and equally sharp acting, as any good series needs to be.