Narcoqueens, Beauty Queens, and Melodrama in Narconarratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Mexico, 1999-2002

ORGANIZED CRIME AND TERRORIST ACTIVITY IN MEXICO, 1999-2002 A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the United States Government February 2003 Researcher: Ramón J. Miró Project Manager: Glenn E. Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Mexico PREFACE This study is based on open source research into the scope of organized crime and terrorist activity in the Republic of Mexico during the period 1999 to 2002, and the extent of cooperation and possible overlap between criminal and terrorist activity in that country. The analyst examined those organized crime syndicates that direct their criminal activities at the United States, namely Mexican narcotics trafficking and human smuggling networks, as well as a range of smaller organizations that specialize in trans-border crime. The presence in Mexico of transnational criminal organizations, such as Russian and Asian organized crime, was also examined. In order to assess the extent of terrorist activity in Mexico, several of the country’s domestic guerrilla groups, as well as foreign terrorist organizations believed to have a presence in Mexico, are described. The report extensively cites from Spanish-language print media sources that contain coverage of criminal and terrorist organizations and their activities in Mexico. -

Violence Within: Understanding the Use of Violent Practices Among Mexican Drug Traffickers

Violence within: Understanding the Use of Violent Practices Among Mexican Drug Traffickers By Dr. Karina García JUSTICE IN MEXICO WORKING PAPER SERIES Volume 16, Number 2 November 2019 About Justice in Mexico: Started in 2001, Justice in Mexico (www.justiceinmexico.org) is a program dedicated to promoting analysis, informed public discourse, and policy decisions; and government, academic, and civic cooperation to improve public security, rule of law, and human rights in Mexico. Justice in Mexico advances its mission through cutting-edge, policy-focused research; public education and outreach; and direct engagement with policy makers, experts, and stakeholders. The program is presently based at the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of San Diego (USD), and involves university faculty, students, and volunteers from the United States and Mexico. From 2005 to 2013, the program was based at USD’s Trans-Border Institute at the Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies, and from 2001 to 2005 it was based at the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies at the University of California-San Diego. About this Publication: This paper forms part of the Justice in Mexico working paper series, which includes recent works in progress on topics related to crime and security, rule of law, and human rights in Mexico. All working papers can be found on the Justice in Mexico website: www.justiceinmexico.org. The research for this paper involved in depth interviews with over thirty participants in violent aspects of the Mexican drug trade, and sheds light on the nature and purposes of violent activities conducted by Mexican organized crime groups. -

Pink Unicorn Program

M T H A E Y E OUT OF THE BOX 9 P I - S 2 C 5 THEATRICS O , P 2 A 0 L 1 A presents 9 C T O R A L I C E R I P L E Y in S ' G U I L D MUSIC & LYRICS BY STEPHEN SONDHEIM BOOK BY JAMES LAPINE BOOK E L I S E F O R I E R E D I E DIRECTION A M Y E . J O N E S @ootbtheatrics Opening Night: May 15, 2019 The Episcopal Actors' Guild 1 East 29th Street Elizabeth Flemming Ethan Paulini Producing Artistic Director Associate Artistic Director present Alice Ripley* in Out of the Box Theatrics' production of By Elise Forier Edie Technical Design Dialect Coach Costume Design Frank Hartley Rena Cook Hunter Dowell Board Operator Wardrobe Supervisor Joshua Christensen Carrie Greenberg Graphic Design General Management Asst. General Management Gabriella Garcia Maggie Snyder Cara Feuer Press Representative Production Stage Management Ron Lasko Theresa S. Carroll* Directed by AMY E. JONES+ * Actors' Equity OOTB is proud to hire members of + Stage Directors and Association Choreographers Society AUTHOR'S NOTE ELISE FORIER EDIE People often ask me “how much of this play is true?” The answer is, “All of it.” Also, “None of it.” All the events in this play happened to somebody. High school students across the country have been forbidden to start Gay and Straight Alliance clubs. The school picture event mentioned in this play really did happen to a child in Florida. Families across the country are being shunned, harassed and threatened by neighbors, and they suffer for allowing their transgender children to freely express their identities. -

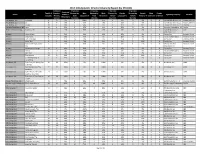

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By STUDIO)

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by STUDIO) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Female Studio Title Female + Signatory Company Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A+E Studios, LLC Knightfall 2 0 0% 2 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC Six 8 4 50% 4 50% 1 13% 3 38% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC UnReal 10 4 40% 6 60% 0 0% 2 20% 2 20% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC Lifetime Alameda Productions, LLC Love 12 4 33% 8 67% 0 0% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0 Alameda Productions, LLC Netflix Alcon Television Group, Expanse, The 13 2 15% 11 85% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Expanding Universe Syfy LLC Productions, LLC Amazon Hand of God 10 5 50% 5 50% 2 20% 3 30% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon I Love Dick 8 7 88% 1 13% 0 0% 7 88% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow Streaming Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Just Add Magic 26 7 27% 19 73% 0 0% 4 15% 1 4% 0 2 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Kicks, The 9 2 22% 7 78% 0 0% 0 0% 2 22% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Man in the High Castle, 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0 Reunion MITHC 2 Amazon Prime The Productions Inc. -

Visualidad Política De América Latina En Narcos: Un Análisis a Través Del Estilo Televisivo

° www. comunicacionymedios.uchile.cl 106 Comunicación y Medios N 37 (2018) Visualidad política de América Latina en Narcos: un análisis a través del estilo televisivo Political visuality of Latin America in Narcos: an analysis through the television style Simone Rocha Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brasil [email protected] Resumen Abstract Desde la fundamentación teórica ofrecida por From the theoretical approach of the visual stu- los estudios visuales articulados al análisis del dies articulated with television style analysis, I estilo televisivo, propongo analizar visualidades intend to analyze visualities of Latin America de América Latina y de eventos históricos que and historical events on the contemporary drug tratan la problemática contemporánea de las problem exhibited in the first season of Narcos drogas exhibidas en la primera temporada de (Netflix, 2015). Based on the primary meaning Narcos (Netflix, 2015). A partir de la identifica- established by the producers, it is possible to ción del sentido tutor, definido por los realizado- understand the complex relationships between res de la serie, es posible captar las complejas crime, economy, formal politics and corruption. relaciones establecidas entre crimen, economía, política formal y corrupción. Keywords Visuality; Narcos; Latin America; Television Style. Palabras clave Visualidad; Narcos; América Latina; estilo tele- visivo. Recibido: 10-03-2018/ Aceptado: 08-06-2018 / Publicado: 30-06-2018 DOI: 10.5354/0719-1529.2018.48572 Visualidad política -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Teoría Y Evolución De La Telenovela Latinoamericana

TEORÍA Y EVOLUCIÓN DE LA TELENOVELA LATINOAMERICANA Laura Soler Azorín Laura Soler Azorín Soler Laura TEORÍA Y EVOLUCIÓN DE LA TELENOVELA LATINOAMERICANA Laura Soler Azorín Director: José Carlos Rovira Soler Octubre 2015 TEORÍA Y EVOLUCIÓN DE LA TELENOVELA LATINOAMERICANA Laura Soler Azorín Tesis de doctorado Dirigida por José Carlos Rovira Soler Universidad de Alicante Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Departamento de Filología Española, Lingüística General y Teoría de la Literatura Octubre 2015 A Federico, mis “manos” en selectividad. A Liber, por tantas cosas. Y a mis padres, con quienes tanto quiero. AGRADECIMIENTOS. A José Carlos Rovira. Amalia, Ana Antonia, Antonio, Carmen, Carmina, Carolina, Clarisa, Eleonore, Eva, Fernando, Gregorio, Inma, Jaime, Joan, Joana, Jorge, Josefita, Juan Ramón, Lourdes, Mar, Patricia, Rafa, Roberto, Rodolf, Rosario, Víctor, Victoria… Para mis compañeros doctorandos, por lo compartido: Clara, Jordi, María José y Vicent. A todos los que han ESTADO a mi lado. Muy especialmente a Vicente Carrasco. Y a Bernat, mestre. ÍNDICE 1.- INTRODUCCIÓN. 1.1.- Objetivos y metodología (pág. 11) 1.2.- Análisis (pág. 11) 2.- INTRODUCCIÓN. UN ACERCAMIENTO AL “FENÓMENO TELENOVELA” EN ESPAÑA Y EN EL MUNDO 2.1.-Orígenes e impacto social y económico de la telenovela hispanoamericana (pág. 23) 2.1.1.- El incalculable negocio de la telenovela (pág. 26) 2.2.- Antecedentes de la telenovela (pág. 27) 2.2.1.- La novela por entregas o folletín como antecedente de la telenovela actual. (pág. 27) 2.2.2.- La radionovela, predecesora de la novela por entregas y antecesora de la telenovela (pág. 35) 2.2.3.- Elementos comunes con la novela por entregas (pág. -

Transnational Cartels and Border Security”

STATEMENT OF PAUL E. KNIERIM DEPUTY CHIEF OF OPERATIONS OFFICE OF GLOBAL ENFORCEMENT DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON BORDER SECURITY AND IMMIGRATION UNITED STATES SENATE FOR A HEARING ENTITLED “NARCOS: TRANSNATIONAL CARTELS AND BORDER SECURITY” PRESENTED DECEMBER 12, 2018 Statement of Paul E. Knierim Deputy Chief of Operations, Office of Global Enforcement Drug Enforcement Administration Before the Subcommittee on Border Security and Immigration United States Senate December 12, 2018 Mr. Chairman, Senator Cornyn, distinguished Members of the subcommittee – on behalf of Acting Drug Enforcement Administrator Uttam Dhillon and the men and women of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), thank you for holding this hearing on Mexican Cartels and Border Security and for allowing the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to share its views on this very important topic. It is an honor to be here to discuss an issue that is important to our country and its citizens, our system of justice, and about which I have dedicated my professional life and personally feel very strongly. I joined the DEA in 1991 as a Special Agent and was initially assigned to Denver, and it has been my privilege to enforce the Controlled Substances Act on behalf of the American people for over 27 years now. My perspective on Mexican Cartels is informed by my years of experience as a Special Agent in the trenches, as a Supervisor in Miami, as an Assistant Special Agent in Charge in Dallas to the position of Assistant Regional Director for the North and Central America Region, and now as the Deputy Chief of Operations for DEA. -

Drug Violence in Mexico

Drug Violence in Mexico Data and Analysis Through 2013 SPECIAL REPORT By Kimberly Heinle, Octavio Rodríguez Ferreira , and David A. Shirk Justice in Mexico Project Department of Political Science & International Relations University of San Diego APRIL 2014 About Justice in Mexico: Started in 2001, Justice in Mexico (www.justiceinmexico.org) is a program dedicated to promoting analysis, informed public discourse and policy decisions; and government, academic, and civic cooperation to improve public security, rule of law, and human rights in Mexico. Justice in Mexico advances its mission through cutting-edge, policy-focused research; public education and outreach; and direct engagement with policy makers, experts, and stakeholders. The program is presently based at the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of San Diego (USD), and involves university faculty, students, and volunteers from the United States and Mexico. From 2005-2013, the project was based at the USD Trans-Border Institute at the Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies, and from 2001-2005 it was based at the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies at the University of California- San Diego. About the Report: This is one of a series of special reports that have been published on a semi-annual by Justice in Mexico since 2010, each of which examines issues related to crime and violence, judicial sector reform, and human rights in Mexico. The Drug Violence in Mexico report series examines patterns of crime and violence attributable to organized crime, and particularly drug trafficking organizations in Mexico. This report was authored by Kimberly Heinle, Octavio Rodríguez Ferreira, and David A. -

Celebrating Uncommon Courage

th Celebrating5 Annual Gala Uncommon Courage Hollywood, CA | March 28, 2018 Hosted by Lauren Ash Mission The California Fire Foundation, a non-profit 501 (c)(3) organization, aids fallen firefighter families, firefighters and the communities they protect. Owned and operated by California Professional Firefighters (California Lou Paulson Professional Firefighters is the largest Chair of California Fire Foundation statewide organization dedicated exclusively President of California Professional Firefighters Over 30 years in the Fire Service to serving the needs of career firefighters), the California Fire Foundation’s mandate includes an array of survivor and victim assistance projects and community initiatives. Note from the Chair As a former career firefighter, I have experienced the shattering loss of comrades on the frontlines, and seen countless tragedies affecting the people and communities of this great state that I love. Not too long ago, we could expect fire season to last a couple of months, however the “new normal” we have come to endure is a year-long fire season. California’s ongoing drought has greatly exacerbated this compound threat to public safety, creating a deadly mix of hotter, more intense and more unpredictable fires. This current state of affairs has severely heightened the risk of life, limb and property of our citizens and our first responders. When tragedy strikes, whether it’s a fallen firefighter’s family at home or the station that are left behind, or the victims of fire and natural disaster that are left in peril, it is my priority, as Chair of the California Fire Foundation, to assist those impacted. We are there at every step, providing aid to our first responders, families of the fallen, and victims of devastating loss. -

Love and Class in Mexican Neoliberal Cinema

Regimes of Affect: Love and Class in Mexican Neoliberal Cinema Ignacio M. Sánchez Prado Published online: February 2014 http://www.jprstudies.org Abstract: Departing from the idea of studying affects and emotions in their relationship to contemporary capitalism, this article explores the way in which love stories have evolved in Mexican cinema of the past 20 years to accommodate the social divisions produced by neoliberal social and economic reform. The article argues that Mexican commercial cinema, led by a boom in the romantic comedy, caters a narrative that idealizes what Richard Florida calls “the creative class” and thus constructs a regime of affect that proactively segregates audiences by class. This thesis is developed through the study of works by filmmakers such as Alfonso Cuarón (Sólo con tu pareja), Antonio Serrano (Sexo, pudor y lágrimas) and Fernando Sariñana (Amar te duele). About the Author: Ignacio M. Sánchez Prado is Associate Professor of Spanish and International and Area Studies at Washington University in Saint Louis. He is the author of El canon y sus formas. La reinvención de Harold Bloom y sus lecturas hispanoamericanas (2002), Naciones intelectuales. Las fundaciones de la modernidad literaria mexicana (1917- 1959) (2009), winner of the LASA Mexico 2010 Humanities Book Award, and Intermitencias americanistas. Ensayos académico y literarios (2004-2009) (2012), a collection of his essays on the question of Latin Americanism. He has edited and co-edited nine scholarly collections and published over forty scholarly articles on Mexican literature, culture and film, as well as on Latin American cultural theory. His next book, Screening Neoliiberalism. Mexican Cinema 1988-2012, explores the connections between film and neoliberalism in contemporary Mexico and will be published by Vanderbilt University Press in 2014. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003-