Alaska Bar Association Ethics Opinion No. 2005-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

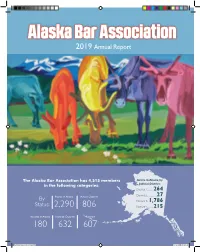

2019 Annual Report

Alaska Bar Association 2019 Annual Report The Alaska Bar Association has 4,515 members Active in Alaska, by in the following categories: Judicial District: District 1 ............264 Active in Alaska Active Outside District 2 ..................27 By District 3 ...1,786 Status: 2,290 806 District 4 ............215 Inactive in Alaska Inactive Outside Retired 180 632 607 2019 annual report.indd 1 3/12/20 12:32 PM Alaska Bar Association — 2019 Annual Report Admissions/Licensing Mandatory Continuing Legal Education 2019 BAR EXAM RESULTS Date Applicants Passed Feb. 2019 32 12 2,927 Active Bar members are required to: 1st time takers 17 10 • earn at least 3 CLE ethics credits July 2019 57 32 1st time takers 44 28 • encouraged to earn at least 9 additional credits UBE: Alaska administers the Uniform Bar • report MCLE compliance annually Exam (UBE) with the passing score set at 280. reported compliance The Alaska Supreme Court asked the Board 99.8% of Governors to review the cut score and 55% reported earning at least 12 credits whether it should remain the same. The Board recommended that the passing score remain at 20% reported earning between 3 and 11 credits 280. 25% reported earning only 3 ethics credits 34 applicants were approved for admission by UBE score transfer. 5 Bar members were administratively 43 applicants were approved for admission by suspended for failure to comply reciprocity. Alaska continues to conduct its own character investigations. The Bar uses an admissions database which allows applicants to enter their information directly into the system. Member Services CLE • ALPS (Attorney Liability Protection Society) is the Bar endorsed CLE programs were delivered in a variety of malpractice insurance company. -

7-Night Mexican Riviera

7-night Mexican Riviera on the brand-new Carnival Panorama February 8-15, 2020 Sponsored by the Alaska Bar Association Ports of Call: in cooperation with: Long Beach, California Colorado Bar Association CLE State Bar of Montana State Bar of Georgia Nebraska State Bar Association Cabo San Lucas, Mexico Hawai‘i State Bar Association Oklahoma Bar Association Idaho Law Foundation, Inc. Oregon State Bar Mazatlan, Mexico Kansas Bar Association South Carolina Bar Puerto Vallarta, Mexico Maine State Bar Association Wyoming State Bar Maryland State Bar Association (DE, PA, VA) Al Mar Para Aprender To Sea To Learn Learn How to Swim Waves of Wellness: Learning Like a Tax Shark Techniques that Reduce 1.5 hours Stress and Anxiety Christy Lee Presented by 1.5 hours Drowning in tax issues related to your law practice? This Presented by Nancy Nolin course focuses on turning you into a tax shark, one who manages your law firm as a bona fide moneymaking enterprise. This workshop will focus on tools in reshaping and enhancing You’ll bite into proactive strategies that can minimize tax your management of stressful situations. liability while helping to audit-proof your business. And you’ll discover how to maximize your chances for financial success. Winning from the Beginning; Keeping Your Head Opening Statements 2.0 hours Above Water Presented by M. Shane Henry 3.0 hours This presentation covers Techniques, Tips and Trial hacks Presented by Bar Counsel, Nelson Page for successful Opening Statements. Discussion includes Nelson Page will discuss the ethics and practice issues that persuasive techniques, structure and body movement. -

104(A)(1) of the Code of Professional Responsibility

ALASKA BAR ASSOCIATION ETHICS OPINION 90-1 Attorney Representing Dissenting Shareholders/Directors Communicating with Board of Directors without Consent of Corporation's Attorney The Committee has been requested to give an opinion as to whether it is improper for an attorney who represents two corporate directors, in their individual capacity, in a shareholder derivative action to discuss matters relating to the pending litigation with other board members when the corporation is represented by both corporate counsel and retained litigation counsel who have not consented to the communication. It is the opinion of the Committee that the communication is in violation of Disciplinary Rule 7- 104(a)(1) of the Code of Professional Responsibility. Disciplinary Rule 7-104(A)(1) provides as follows: During the course of his representation of a client, a lawyer shall not: (1) communicate or cause another to communicate on the subject of the representation with a party he knows to be represented by a lawyer in that matter unless he has prior consent of the lawyer representing such party or is authorized by law to do so. Attorney originally represented three dissenting shareholders who sued a corporation, three board members, and a corporate employee, on their own behalf and in the form of a shareholder's derivative suit, to set aside a corporate transaction. Two of the plaintiffs and the daughter of a third plaintiff were subsequently elected to the board of directors, along with other directors who shared their view. At the time in question, the board was deeply and approximately evenly divided on the propriety of the corporate transaction. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Nationally, approximately 40% of new attorneys work at firms consisting of more than 50 lawyers. Therefore, a large percentage of practicing attorneys work for small firms (fewer than 50 attorneys). Small firms generally do not have formalized recruiting procedures or a set “hiring season” when they recruit summer law clerks, school-year law clerks, or entry-level attorneys. Instead, these firms hire on an as-needed basis, and they hire year round. To secure employment with a small firm, students and lawyers alike need to be proactive in getting their name and interests out in the community. Applicants should not only apply directly to these firms, but they should connect via law school, community, and bar association activities. In this directory, you will find state-by-state hyperlinks to regional directories, bar associations, newspapers, and job banks that can be used to jump-start a small firm search. ALABAMA State/Regional Bar Associations Alabama Bar Association: http://www.alabar.org Birmingham Bar Association: http://www.birminghambar.org Mobile Bar Association: http://www.mobilebar.org Specialty Bar Associations Alabama Defense Lawyers Association: http://www.adla.org Alabama Trial Lawyers Association: http://www.alabamajustice.org Major Newspapers Birmingham News: http://www.al.com/birmingham Mobile Register: http://www.al.com/mobile Legal & Non-Legal Resources & Publications State Lawyers.com: http://alabama.statelawyers.com EINNEWS: http://www.einnews.com/alabama Birmingham Business Journal: http://birmingham.bizjournals.com -

A Revolt in the Ranks: the Great Alaska Court-Bar Fight*

ARTICLES A Revolt in the Ranks: The Great Alaska Court-Bar Fight* PAMELA CRAVEZ** This Article details the post-statehood controversy between the Alaska Supreme Court and the Alaska Bar Association known as the "court-barfight." First,the Article discusses United States v. Stringer, a 1954 attorney discipline case illustrating the territorial courts' perceived inability to regulate adequately the legal Copyright © 1996 by Alaska Law Review * This article is excerpted from Pamela Cravez, Seizing the Frontier, Alaska's Territorial Lawyers (1984) (unpublished manuscript, on file with the author). The author would like to thank Professor Thomas West of Catholic University for his helpful comments on earlier drafts and Jeffrey Mayhook for his insightful editing. She would also like to thank Senior U.S. District Court Judge James M. Fitzgerald, Anchorage District Court Judge James Wanamaker, Glenn Cravez, Joyce Bamberger, Averil Lerman and Patsy Romack for their careful reviews and the Anchorage Bar Association for its generous support of Alaska's Territorial Lawyers: An Oral History. Editor's note: The author has drawn much of the material for this article from Anchorage Bar Ass'n, Alaska's Territorial Lawyers: An Oral History, an unpublished series of taperecorded interviews commissioned by the Anchorage Bar Association and conducted by the author. The audiocassettes are located at the former U.S. District Courthouse in Anchorage, Alaska. Unless otherwise indicated by citation, the information and quotations in this article have been drawn from this source. The editors, however, have not independently verified the information derived from the oral history. Accordingly, we rely on the author's representations as to the authenticity and accuracy of the statements drawn therefrom. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 364 487 SO 023 626 TITLE State and Local

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 364 487 SO 023 626 TITLE State and Local Bar Associations Law-Related Education Activities. INSTITUTION American Bar Association, Chicago, Ill. Special Committee on Youth Education for Citizenship. PUB DATE [93] NOTE 26p.; For related items, see SO 023 625-628. AVAILABLE FROMAmerican Bar Association, Special Committee on Youth Education for Citizenship, 541 N. Fairbanks Court, Chicago, IL 60611-3314. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Alcohol Education; Drug Education; Elementary Secondary Education; *Law Related Education; Lawyers; *Learning Activities; Professional Associations; School Community Relationship; Social Studies; *Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS American Bar Association; Law Day ABSTRACT This document is a listing of the law-related education activities of state and local bar associations grouped by state. Under each state, the state association and often one or more local association are listed. Information on each association includes committees relating to law related education, a listing of law related education activities, funding sources, and the name, address, and phone number of the appropriate contact person. Some association listings also include volunteer recruitment strategies and resources. Listed activities include Law Day, mediation, Lawyer in the Classroom, teen court, mock trials, court docent, bicentennial, teacher education, programs f,31- at-risk youth, and drug prevention projects. The most common funding sources include general operating budgets, bar foundation grants, senior bar funding, Young Lawyers Section activity budgets, and organization dues. Volunteers are recruited by personal appeals, contacts for specific projects, publicity of projects, volunteer sign up sheets in dues packets, special invitations, and articles in organization newsletters. -

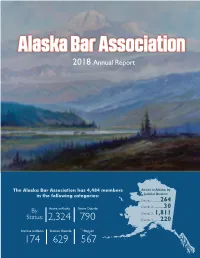

2018 Annual Report

Alaska Bar Association 2018 Annual Report The Alaska Bar Association has 4,484 members Active in Alaska, by in the following categories: Judicial District: District 1 ............264 Active in Alaska Active Outside District 2 ..................30 By District 3 ...1,811 Status: 2,324 790 District 4 ............220 Inactive in Alaska Inactive Outside Retired 174 629 567 Alaska Bar Association — 2018 Annual Report Admissions/Licensing Mandatory Continuing Legal Education 2018 BAR EXAM RESULTS Date Applicants Passed Feb. 2018 39 24 2,927 Active Bar members are required to: 1st time takers 24 18 • earn at least 3 CLE ethics credits July 2018 43 24 1st time takers 36 24 • encouraged to earn at least 9 additional credits UBE: Alaska administers the Uniform Bar • report MCLE compliance annually Exam (UBE) with the passing score set at 280. reported compliance Alaska continues to conduct its own character 99.7% investigations. 54% reported earning at least 12 credits 48 applicants were approved for admission by UBE score transfer. 20% reported earning between 3 and 11 credits 45 applicants were approved for admission by 26% reported earning only 3 ethics credits reciprocity. 8 Bar members were administratively The Bar is using an admissions database which suspended for failure to comply allows applicants to enter their information directly into the system. CLE Member Services CLE programs were delivered in a variety of • ALPS (Attorney Liability Protection formats for the year; with the greatest attendance Society) is the Bar endorsed at 32 live programs. DVD orders malpractice insurance company. 60 (DVD library discontinued) • Casemaker: all Bar members have free access to this online legal Live programs research service. -

Letter to Alaska Bar Association

Department of Law OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL 1031 West Fourth Avenue, Suite 200 Anchorage, Alaska 99501 Main: (907) 269-5100 Fax: (907) 269-5110 August 9, 2019 Board of Governors c/o Robert Stone, President Alaska Bar Association P.O. Box 100279 Anchorage, AK 99510-0279 Re: Proposed Rule of Professional Conduct 8.4(f) Dear Board of Governors: The Alaska Bar Association has solicited comments on an amendment to the Alaska Rules of Professional Conduct. Proposed Rule of Professional Conduct 8.4(f) establishes a new category of professional misconduct. Lawyers who engage in conduct that they know or reasonably should know is harassment or discrimination on the basis of certain identity groups while practicing law, running a firm, or participating in activities connected to legal practice, can be sanctioned. With this rule, the Bar Association intends to promote professionalism, respectfulness, and inclusiveness in the legal profession. Yet the rule wanders far afield of those goals. Parts of the Proposed Rule laudably promote professionalism and respect by attorneys to all individuals regardless of personal traits or characteristics. However, by regulating the expression of ideas and religious practices, Proposed Rule 8.4(f) burdens attorneys’ fundamental constitutional rights and threatens the core of what it means to be an attorney: protecting the rule of law, including the United States Constitution, and advocating zealously for clients. The Proposed Rule would allow the Bar Association to sanction a broad range of expression protected by the United States and Alaska constitutions. Consider the following examples, all of which could be sanctioned under the proposed rule. -

A Comparative Analysis of Rulemaking Procedures and Transparency Practices of Lawyer-Licensing Entities

Campbell University School of Law Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2017 Do It in the Sunshine: A Comparative Analysis of Rulemaking Procedures and Transparency Practices of Lawyer-Licensing Entities Bobbi Jo Boyd Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.campbell.edu/fac_sw Part of the Legal Profession Commons Do IT IN THE SUNSHINE: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF RULEMAKING PROCEDURES AND TRANSPARENCY PRACTICES OF LAWYER-LICENSING ENTITIES Bobbi Jo Boyd INTRODUCTION Regulation of occupational licensing has garnered national attention.) During the last sixty years, the number of occupations regulated by governmental entities has notably increased.2 As the number of regulated occupations increases, employment opportunities and wages for individuals who cannot afford or otherwise meet licensing requirements decrease. 3 In addition to concerns linked to the growing number of occupations requiring licensure, private4 and governmental5 1. U.S. DEP'T OF THE TREASURY OFFICE OF ECON. POLICY, THE COUNCIL OF ECON. ADVISERS, & THE DEP'T OF LABOR, OCCUPATIONAL LICENSING: A FRAMEWORK FOR POLICYMAKERS 3, 6, 17, (2015), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov /sites /default /files /docs/licensing-report finalnonembargo.pdf [https://perma.cc/8DGS-FNCL] [hereinafter OCCUPATIONAL LICENSING: A FRAMEWORK FOR POLICYMAKERS]. 2. Since the 1950s, states have increasingly assumed responsibility for regulating professions practiced within their borders. See Morris M. Kleiner & Alan B. Krueger, Analyzing the Extent and Influence of OccupationalLicensing on the Labor Market, 31 J. LAB. ECON. S173, S175-S176 (2013). Between 1952 and 2008, the number of recorded occupations requiring a license leapt from less than 5% to 29%. See id. -

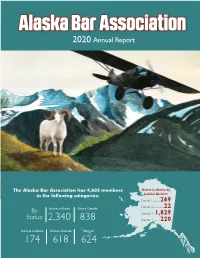

2020 Annual Report

AlaskAlaskaa Bar AsAssociationsociation 2020 Annual Report The Alaska Bar Association has 4,603 members Active in Alaska by in the following categories: Judicial District: District 1 ............269 Active in Alaska Active Outside District 2 ..................22 By District 3 ...1,829 Status: 2,340 838 District 4 ............220 Inactive in Alaska Inactive Outside Retired 174 618 624 AlaskAlaskaa Bar AsAssociationsociation — 2020 AnnAnnualual ReporReportt Admissions/Licensing Mandatory Continuing Legal Education 2020 BAR EXAM RESULTS Date Applicants Passed Feb. 2020 49 23 2,844 Active Bar members are required to: 1st time takers 34 20 • earn at least 3 CLE ethics credits Sept. 2020 50 40 1st time takers 45 40 • encouraged to earn at least 9 additional credits As a result of COVID-19, the July bar exam was • report MCLE compliance annually moved to September. The Bar put protocols in reported compliance place to ensure the safe administration of the 99.6% exam. 53.6% reported earning at least 12 credits UBE: Alaska administers the Uniform Bar Exam (UBE) with the passing score set at 280. 20% reported earning between 3 and 11 credits 46 applicants were approved for admission by 26.4% reported earning only 3 ethics credits UBE score transfer. 9 Bar members were administratively 43 applicants were approved for admission by suspended for failure to comply reciprocity. CLE As a result of COVID-19, the Bar was limited Member Services in the amount of live in-person programs that • ALPS (Attorney Liability it could offer. The 2020 Anchorage Annual Bar Protection Society): Bar endorsed Convention was cancelled. In addition, 25 CLE malpractice insurance company. -

2019 Annual Report

Alaska Bar Association 2019 Annual Report The Alaska Bar Association has 4,515 members Active in Alaska, by in the following categories: Judicial District: District 1 ............264 Active in Alaska Active Outside District 2 ..................27 By District 3 ...1,786 Status: 2,290 806 District 4 ............215 Inactive in Alaska Inactive Outside Retired 180 632 607 Alaska Bar Association — 2019 Annual Report Admissions/Licensing Mandatory Continuing Legal Education 2019 BAR EXAM RESULTS Date Applicants Passed Feb. 2019 32 12 2,927 Active Bar members are required to: 1st time takers 17 10 • earn at least 3 CLE ethics credits July 2019 57 32 1st time takers 44 28 • encouraged to earn at least 9 additional credits UBE: Alaska administers the Uniform Bar • report MCLE compliance annually Exam (UBE) with the passing score set at 280. reported compliance The Alaska Supreme Court asked the Board 99.8% of Governors to review the cut score and 55% reported earning at least 12 credits whether it should remain the same. The Board recommended that the passing score remain at 20% reported earning between 3 and 11 credits 280. 25% reported earning only 3 ethics credits 34 applicants were approved for admission by UBE score transfer. 5 Bar members were administratively 43 applicants were approved for admission by suspended for failure to comply reciprocity. Alaska continues to conduct its own character investigations. The Bar uses an admissions database which allows applicants to enter their information directly into the system. Member Services CLE • ALPS (Attorney Liability Protection Society) is the Bar endorsed CLE programs were delivered in a variety of malpractice insurance company. -

A Revolt in the Ranks: the Great Alaska Court-Bar Fight*

ARTICLES A Revolt in the Ranks: The Great Alaska Court-Bar Fight* PAMELA CRAVEZ** This Article details the post-statehood controversy between the Alaska Supreme Court and the Alaska Bar Association known as the "court-barfight." First,the Article discusses United States v. Stringer, a 1954 attorney discipline case illustrating the territorial courts' perceived inability to regulate adequately the legal Copyright © 1996 by Alaska Law Review * This article is excerpted from Pamela Cravez, Seizing the Frontier, Alaska's Territorial Lawyers (1984) (unpublished manuscript, on file with the author). The author would like to thank Professor Thomas West of Catholic University for his helpful comments on earlier drafts and Jeffrey Mayhook for his insightful editing. She would also like to thank Senior U.S. District Court Judge James M. Fitzgerald, Anchorage District Court Judge James Wanamaker, Glenn Cravez, Joyce Bamberger, Averil Lerman and Patsy Romack for their careful reviews and the Anchorage Bar Association for its generous support of Alaska's Territorial Lawyers: An Oral History. Editor's note: The author has drawn much of the material for this article from Anchorage Bar Ass'n, Alaska's Territorial Lawyers: An Oral History, an unpublished series of taperecorded interviews commissioned by the Anchorage Bar Association and conducted by the author. The audiocassettes are located at the former U.S. District Courthouse in Anchorage, Alaska. Unless otherwise indicated by citation, the information and quotations in this article have been drawn from this source. The editors, however, have not independently verified the information derived from the oral history. Accordingly, we rely on the author's representations as to the authenticity and accuracy of the statements drawn therefrom.