Reaching out (Answer Set)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Committee Virginia State

Virginia State Bar Special Committee THE FUTURE OF LAW PRACTICE 2019 2 Virginia State Bar l Future of Law Practice Committee ©2019 1 1 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................2 TECHNOLOGY AND THE PRACTICE OF LAW .................................................4 2.1 Cybersecurity ......................................................................................................................................................................5 2.2 Current Cybersecurity Statistics .......................................................................................................................................5 2.3 Cyberinsurance and the Morphing of Threats ................................................................................................................7 2 2.4 Cybersecurity Standards ...................................................................................................................................................8 2.5 Data Loss Through Employees .........................................................................................................................................9 2.6 Why are Law Firms So Far Behind in Cybersecurity? ..................................................................................................10 2.7 Encryption ..........................................................................................................................................................................10 2.8 Cloud Computing -

2019 Annual Report

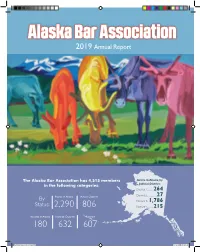

Alaska Bar Association 2019 Annual Report The Alaska Bar Association has 4,515 members Active in Alaska, by in the following categories: Judicial District: District 1 ............264 Active in Alaska Active Outside District 2 ..................27 By District 3 ...1,786 Status: 2,290 806 District 4 ............215 Inactive in Alaska Inactive Outside Retired 180 632 607 2019 annual report.indd 1 3/12/20 12:32 PM Alaska Bar Association — 2019 Annual Report Admissions/Licensing Mandatory Continuing Legal Education 2019 BAR EXAM RESULTS Date Applicants Passed Feb. 2019 32 12 2,927 Active Bar members are required to: 1st time takers 17 10 • earn at least 3 CLE ethics credits July 2019 57 32 1st time takers 44 28 • encouraged to earn at least 9 additional credits UBE: Alaska administers the Uniform Bar • report MCLE compliance annually Exam (UBE) with the passing score set at 280. reported compliance The Alaska Supreme Court asked the Board 99.8% of Governors to review the cut score and 55% reported earning at least 12 credits whether it should remain the same. The Board recommended that the passing score remain at 20% reported earning between 3 and 11 credits 280. 25% reported earning only 3 ethics credits 34 applicants were approved for admission by UBE score transfer. 5 Bar members were administratively 43 applicants were approved for admission by suspended for failure to comply reciprocity. Alaska continues to conduct its own character investigations. The Bar uses an admissions database which allows applicants to enter their information directly into the system. Member Services CLE • ALPS (Attorney Liability Protection Society) is the Bar endorsed CLE programs were delivered in a variety of malpractice insurance company. -

Virginia State Bar MCLE Accredited Sponsors These Sponsors Have a History of Virginia Approved Programs

Virginia State Bar MCLE Accredited Sponsors These sponsors have a history of Virginia approved programs. (Please contact sponsors directly for registration information.) CAUTION: Programs by out-of-state providers may advertise credit for courses that do not meet Virginia’s approval standards under MCLE Regulation 103 and the MCLE Board Opinions. SPONSORS MAY NOT APPLY IN VIRGINIA FOR ALL OF THE COURSES THEY OFFER. The Virginia State Bar is not responsible for content on sponsor websites. SPONSOR PHONE WEBSITE ACC National Capital Region 301-230-1864 www.acc.com/chapters/ncr/ Access MCLE 877-757-6253 www.accessmcle.com Alexandria Bar Association 703-548-1106 www.alexandriabarva.org ALI CLE – American Law Institute 800-253-6397 www.ali-cle.org ALM 212-457-7905 www.almevents.com American Association of Justice 800-622-1791 www.justice.org American Bankruptcy Institute 703-739-0800 www.abi.org American Bar Association 800-285-2221 www.americanbar.org/cle.html American Conference Institute 888-224-2480 www.americanconference.com American Health Lawyers Association 202-833-1100 www.healthlawyers.com American Immigration Lawyers Assoc. 202-507-7600 www.aila.org American Intellectual Property Assoc. 703-415-0780 www.aipla.org American Society of International Law 202-939-6000 www.asil.org American Society of Law, Medicine & 617-262-4990 www.aslme.org American University WCL 202-274-4075 www.wcl.american.edu/secle Arlington County Bar Association 703-228-3390 www.arlingtonbar.org Attorney Credits 877-910-6253 www.attorneycredits.com Attorney -

Volume 25 No. 5 Sep/Oct 2012 FALL FORUM

FALL FORUM Sep/Oct 2012 5 25No. Volume November 8-9 Utah Bar® JOURNAL EISENBERG GILCHRIST & CUTT TTORNEYS AT AW Results Matter Some of our successes in 2011 include: More than 300 lawyers have referred injured clients to • $5.0 million recovery for trucking accident Eisenberg Gilchrist & Cutt because they know we get top results. We approach every case as a serious piece of litigation, • $4.0 million recovery for product liability case whether it is worth $100,000 or $10 million. • $2.8 million recovery for carbon monoxide case • $2.5 million recovery for auto-wrongful death Call us if you have a new injury case or want to bring • $1.5 million jury verdict for ski accident case experience to a pending case. We tailor fee arrangements to • $1.1 million recovery for medical malpractice suit your clients’ needs, and we help fund litigation costs. Let our experience add value to your case. 900 PARKSIDE TOWER • 215 SOUTH STATE STREET • SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH 84111 TEL: 801-366-9100 TOL-FREE: 877-850-3030 WWW.EISENBERGANDGILCHRIST.COM FOUNDING PARTNERS ARE JEFFREY D. EISENBERG, ROBERT G. GILCHRIST AND DAVID A. CUTT Table of Contents Utah Ba President’s Message: Looking Ahead 6 by Lori W. Nelson EISENBERG GILCHRIST & CUTT Commission Message: Modest Means Lawyer Referral Program: TTORNEYS AT AW How You Can Make this Program Work for Your Practice 10 r by Hon. Su J. Chon ® Article: Twombly and Iqbal: How the Supreme Court has Radically Redefined Access to the Federal Courts 12 by Aaron S. Bartholomew JOURNAL Article: The New Respect for Justice George Sutherland 18 by Andrew M. -

7-Night Mexican Riviera

7-night Mexican Riviera on the brand-new Carnival Panorama February 8-15, 2020 Sponsored by the Alaska Bar Association Ports of Call: in cooperation with: Long Beach, California Colorado Bar Association CLE State Bar of Montana State Bar of Georgia Nebraska State Bar Association Cabo San Lucas, Mexico Hawai‘i State Bar Association Oklahoma Bar Association Idaho Law Foundation, Inc. Oregon State Bar Mazatlan, Mexico Kansas Bar Association South Carolina Bar Puerto Vallarta, Mexico Maine State Bar Association Wyoming State Bar Maryland State Bar Association (DE, PA, VA) Al Mar Para Aprender To Sea To Learn Learn How to Swim Waves of Wellness: Learning Like a Tax Shark Techniques that Reduce 1.5 hours Stress and Anxiety Christy Lee Presented by 1.5 hours Drowning in tax issues related to your law practice? This Presented by Nancy Nolin course focuses on turning you into a tax shark, one who manages your law firm as a bona fide moneymaking enterprise. This workshop will focus on tools in reshaping and enhancing You’ll bite into proactive strategies that can minimize tax your management of stressful situations. liability while helping to audit-proof your business. And you’ll discover how to maximize your chances for financial success. Winning from the Beginning; Keeping Your Head Opening Statements 2.0 hours Above Water Presented by M. Shane Henry 3.0 hours This presentation covers Techniques, Tips and Trial hacks Presented by Bar Counsel, Nelson Page for successful Opening Statements. Discussion includes Nelson Page will discuss the ethics and practice issues that persuasive techniques, structure and body movement. -

Alaska Bar Association Ethics Opinion No. 2005-1

ALASKA BAR ASSOCIATION ETHICS OPINION NO. 2005-1 Responsibilities of the Attorney Representing a Client Who, After Being Charged with a Felony Offense, Informs the Attorney of the Client’s Intent to Commit Suicide if Convicted Question Presented An attorney represents a client charged with felony sexual assault, but realizes that the client has no credible defense. The client, however, is not interested in a plea bargain and is adamant about taking the case to trial. The client has further informed the attorney that if convicted of the felony sexual assault, the client will commit suicide rather than go to jail. Must the attorney disclose the client’s stated intention to commit suicide rather than go to jail if convicted? The Committee concludes that under ARCP 1.14, the attorney may disclose the client’s stated intent to commit suicide to the proper authorities (e.g., the court, appropriate mental health professionals, or appropriate detention facility personnel) irrespective of the client’s custodial status, but is not required to do so.1 The Alaska Bar Association joins the American Bar Association and the several other state bar associations that have addressed this issue. These associations have determined that disclosure of a client’s suicidal intent is permissible.2 1 ARCP 1.14 provides in pertinent part that a lawyer “may . take other protective action with respect to a client only when the lawyer reasonably believes that the client cannot adequately act in the client’s own interest.” 2 See ABA Informal Opinion 83-1500 (1983); Alabama Ethics Opinion RO- 90-06; 74 Conn. -

104(A)(1) of the Code of Professional Responsibility

ALASKA BAR ASSOCIATION ETHICS OPINION 90-1 Attorney Representing Dissenting Shareholders/Directors Communicating with Board of Directors without Consent of Corporation's Attorney The Committee has been requested to give an opinion as to whether it is improper for an attorney who represents two corporate directors, in their individual capacity, in a shareholder derivative action to discuss matters relating to the pending litigation with other board members when the corporation is represented by both corporate counsel and retained litigation counsel who have not consented to the communication. It is the opinion of the Committee that the communication is in violation of Disciplinary Rule 7- 104(a)(1) of the Code of Professional Responsibility. Disciplinary Rule 7-104(A)(1) provides as follows: During the course of his representation of a client, a lawyer shall not: (1) communicate or cause another to communicate on the subject of the representation with a party he knows to be represented by a lawyer in that matter unless he has prior consent of the lawyer representing such party or is authorized by law to do so. Attorney originally represented three dissenting shareholders who sued a corporation, three board members, and a corporate employee, on their own behalf and in the form of a shareholder's derivative suit, to set aside a corporate transaction. Two of the plaintiffs and the daughter of a third plaintiff were subsequently elected to the board of directors, along with other directors who shared their view. At the time in question, the board was deeply and approximately evenly divided on the propriety of the corporate transaction. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Nationally, approximately 40% of new attorneys work at firms consisting of more than 50 lawyers. Therefore, a large percentage of practicing attorneys work for small firms (fewer than 50 attorneys). Small firms generally do not have formalized recruiting procedures or a set “hiring season” when they recruit summer law clerks, school-year law clerks, or entry-level attorneys. Instead, these firms hire on an as-needed basis, and they hire year round. To secure employment with a small firm, students and lawyers alike need to be proactive in getting their name and interests out in the community. Applicants should not only apply directly to these firms, but they should connect via law school, community, and bar association activities. In this directory, you will find state-by-state hyperlinks to regional directories, bar associations, newspapers, and job banks that can be used to jump-start a small firm search. ALABAMA State/Regional Bar Associations Alabama Bar Association: http://www.alabar.org Birmingham Bar Association: http://www.birminghambar.org Mobile Bar Association: http://www.mobilebar.org Specialty Bar Associations Alabama Defense Lawyers Association: http://www.adla.org Alabama Trial Lawyers Association: http://www.alabamajustice.org Major Newspapers Birmingham News: http://www.al.com/birmingham Mobile Register: http://www.al.com/mobile Legal & Non-Legal Resources & Publications State Lawyers.com: http://alabama.statelawyers.com EINNEWS: http://www.einnews.com/alabama Birmingham Business Journal: http://birmingham.bizjournals.com -

A Revolt in the Ranks: the Great Alaska Court-Bar Fight*

ARTICLES A Revolt in the Ranks: The Great Alaska Court-Bar Fight* PAMELA CRAVEZ** This Article details the post-statehood controversy between the Alaska Supreme Court and the Alaska Bar Association known as the "court-barfight." First,the Article discusses United States v. Stringer, a 1954 attorney discipline case illustrating the territorial courts' perceived inability to regulate adequately the legal Copyright © 1996 by Alaska Law Review * This article is excerpted from Pamela Cravez, Seizing the Frontier, Alaska's Territorial Lawyers (1984) (unpublished manuscript, on file with the author). The author would like to thank Professor Thomas West of Catholic University for his helpful comments on earlier drafts and Jeffrey Mayhook for his insightful editing. She would also like to thank Senior U.S. District Court Judge James M. Fitzgerald, Anchorage District Court Judge James Wanamaker, Glenn Cravez, Joyce Bamberger, Averil Lerman and Patsy Romack for their careful reviews and the Anchorage Bar Association for its generous support of Alaska's Territorial Lawyers: An Oral History. Editor's note: The author has drawn much of the material for this article from Anchorage Bar Ass'n, Alaska's Territorial Lawyers: An Oral History, an unpublished series of taperecorded interviews commissioned by the Anchorage Bar Association and conducted by the author. The audiocassettes are located at the former U.S. District Courthouse in Anchorage, Alaska. Unless otherwise indicated by citation, the information and quotations in this article have been drawn from this source. The editors, however, have not independently verified the information derived from the oral history. Accordingly, we rely on the author's representations as to the authenticity and accuracy of the statements drawn therefrom. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 364 487 SO 023 626 TITLE State and Local

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 364 487 SO 023 626 TITLE State and Local Bar Associations Law-Related Education Activities. INSTITUTION American Bar Association, Chicago, Ill. Special Committee on Youth Education for Citizenship. PUB DATE [93] NOTE 26p.; For related items, see SO 023 625-628. AVAILABLE FROMAmerican Bar Association, Special Committee on Youth Education for Citizenship, 541 N. Fairbanks Court, Chicago, IL 60611-3314. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Alcohol Education; Drug Education; Elementary Secondary Education; *Law Related Education; Lawyers; *Learning Activities; Professional Associations; School Community Relationship; Social Studies; *Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS American Bar Association; Law Day ABSTRACT This document is a listing of the law-related education activities of state and local bar associations grouped by state. Under each state, the state association and often one or more local association are listed. Information on each association includes committees relating to law related education, a listing of law related education activities, funding sources, and the name, address, and phone number of the appropriate contact person. Some association listings also include volunteer recruitment strategies and resources. Listed activities include Law Day, mediation, Lawyer in the Classroom, teen court, mock trials, court docent, bicentennial, teacher education, programs f,31- at-risk youth, and drug prevention projects. The most common funding sources include general operating budgets, bar foundation grants, senior bar funding, Young Lawyers Section activity budgets, and organization dues. Volunteers are recruited by personal appeals, contacts for specific projects, publicity of projects, volunteer sign up sheets in dues packets, special invitations, and articles in organization newsletters. -

Goldfarb V. Virginia State Bar: the Professions Are Subject to the Sherman Act

Missouri Law Review Volume 41 Issue 1 Winter 1976 Article 6 Winter 1976 Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar: The Professions Are Subject to the Sherman Act Richard B. Tyler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard B. Tyler, Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar: The Professions Are Subject to the Sherman Act, 41 MO. L. REV. (1976) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol41/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tyler: Tyler: Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar: MISSOURI LAW REVIEW Volume 41 Winter 1976 Number 1 GOLDFARB V. VIRGINIA STATE BAR: THE PROFESSIONS ARE SUBJECT TO THE SHERMAN ACT Richard B. Tyler* I. INTRODUCTION "The nature of an occupation, standing alone, does not provide sanctuary from the Sherman Act ... nor is the public service aspect of professional practice controlling in determining whether § 1 includes professions. ..." With these words, the United States Supreme Court established the applicability of the Sherman Act 2 to the "learned pro- fessions." The import of the Court's holding has not been lost on the anti- trust enforcement agencies. They have recently filed suit or announced in- vestigations of the activities of other professional organizations.3 Some professionals, on the other hand, have attempted to read the decision OAsst. -

2018 Annual Report

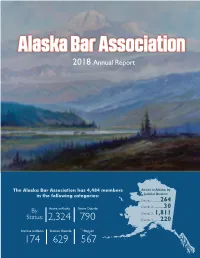

Alaska Bar Association 2018 Annual Report The Alaska Bar Association has 4,484 members Active in Alaska, by in the following categories: Judicial District: District 1 ............264 Active in Alaska Active Outside District 2 ..................30 By District 3 ...1,811 Status: 2,324 790 District 4 ............220 Inactive in Alaska Inactive Outside Retired 174 629 567 Alaska Bar Association — 2018 Annual Report Admissions/Licensing Mandatory Continuing Legal Education 2018 BAR EXAM RESULTS Date Applicants Passed Feb. 2018 39 24 2,927 Active Bar members are required to: 1st time takers 24 18 • earn at least 3 CLE ethics credits July 2018 43 24 1st time takers 36 24 • encouraged to earn at least 9 additional credits UBE: Alaska administers the Uniform Bar • report MCLE compliance annually Exam (UBE) with the passing score set at 280. reported compliance Alaska continues to conduct its own character 99.7% investigations. 54% reported earning at least 12 credits 48 applicants were approved for admission by UBE score transfer. 20% reported earning between 3 and 11 credits 45 applicants were approved for admission by 26% reported earning only 3 ethics credits reciprocity. 8 Bar members were administratively The Bar is using an admissions database which suspended for failure to comply allows applicants to enter their information directly into the system. CLE Member Services CLE programs were delivered in a variety of • ALPS (Attorney Liability Protection formats for the year; with the greatest attendance Society) is the Bar endorsed at 32 live programs. DVD orders malpractice insurance company. 60 (DVD library discontinued) • Casemaker: all Bar members have free access to this online legal Live programs research service.