THE STATE of the BALTIMORE REGION a Baseline Report for a New Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19-1189 BP PLC V. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus BP P. L. C. ET AL. v. MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL OF BALTIMORE CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT No. 19–1189. Argued January 19, 2021—Decided May 17, 2021 Baltimore’s Mayor and City Council (collectively City) sued various en- ergy companies in Maryland state court alleging that the companies concealed the environmental impacts of the fossil fuels they promoted. The defendant companies removed the case to federal court invoking a number of grounds for federal jurisdiction, including the federal officer removal statute, 28 U. S. C. §1442. The City argued that none of the defendants’ various grounds for removal justified retaining federal ju- risdiction, and the district court agreed, issuing an order remanding the case back to state court. Although an order remanding a case to state court is ordinarily unreviewable on appeal, Congress has deter- mined that appellate review is available for those orders “remanding a case to the State court from which it was removed pursuant to section 1442 or 1443 of [Title 28].” §1447(d). The Fourth Circuit read this provision to authorize appellate review only for the part of a remand order deciding the §1442 or §1443 removal ground. -

Understanding Divided Baltimore

UNDERSTANDING DIVIDED BALTIMORE How Data, Especially Mapped Data, Informed the Course WHAT WE WERE TRYING TO DO • Divided Baltimore was a UB response to the events of April 2015. • We wanted to share information widely with students and with interested community members with hope that we could catalyze interest in learning how Baltimore became so divided. • Presentations built around a community forum • Graduate, undergraduate, and dual enrollment high school students were enrolled in sections of the course with their own instructor. THE NEW YORK TIMES CAPTURED HOW WE ORGANIZED THE COMMUNITY FORUM http://www.nytimes.com/video/us/100000003 973175/uniting-a-divided-baltimore.html October 20, 2015 - By A.J. CHAVAR - U.S. - Print Headline: "Uniting a Divided Baltimore“ USING DATA AND MAPS IN THE COURSE • Today, we want to report on how we relied on the good work of BNIA and many of you in compiling data and maps that help immeasurably in comprehending the issues we face in Baltimore in achieving a fair society. HISTORICAL DATA AND MAPS— BETSY NIX • UB History Professor Betsy Nix developed a lecture on the history of segregation in Baltimore that she has now presented to a range of agencies and groups from Annie E. Casey to OSI to the last round of Baltimore City Police recruits. 1860 212,418 residents 25,500 or 12% free people of color from Freedom’s Port 1937 Redlining Map The Baltimore Chop The Baltimore Chop Map from Study for East-West Expressway, 1957. Johns Hopkins University, Sheridan Libraries. Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance, -

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore V. Baltimore and Philadelphia Steamboat Company, 65 A. 353, 104 Md. 485 (Dec

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Baltimore and Philadelphia Steamboat Company, 65 A. 353, 104 Md. 485 (Dec. 19, 1906) Russell K. George I. INTRODUCTION Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Baltimore and Philadelphia Steamboat Company1 concerns the condemnation by the City of Baltimore of properties owned by the Baltimore and Philadelphia Steamboat Company ("BPSC"). After the Great Fire of 1904, which destroyed most of the Baltimore business district, the City embarked on an effort to make various urban improvements. Among other things, the City endeavored to widen Pratt Street fifty feet to the south by condemning wharves at the corner of Light and Pratt Streets that were owned and leased by the Steamboat Company.2 The Burnt District Commission awarded the Company minimal damages for the property that was condemned, and instead assessed benefits against the Company for the widening of Pratt Street.3 The Company appealed to the Baltimore City Circuit Court, where Judge Henry Stockbridge essentially reversed the Commission awards, giving the Company much more compensation than it initially received. Both the City and the Company cross- appealed. The Maryland Court of Appeals rendered its decision on December 19, 1906, affirming Stockbridge's awards. The case represents a microcosm of the improvement efforts in Baltimore following the fire. The litigation pursued by the Steamboat Company shows how property owners posed an obstacle to urban improvements. Christine Rosen discusses this in The Limits of Power: Great Fires and the Process of City Growth in America, 1 65 A. 353 (1906). 2 See Diagram, attached. 1 concluding that the progressive nature of Baltimore, which had developed prior to the fire,4 helped the City to overcome various obstacles to change, including private property ownership and political deadlock.5 In addition, the case presents issues concerning the condemnation value of waterfront property, particularly the value of certain riparian rights and the question of whether they are to be included in the fair market value of the property. -

COMMUNITY SCHOOLS Case Studies of What Works

COMMUNITY SCHOOLS Case studies of what works Baltimore 03 Maryland 03 BALTIMORE CITY COMMUNITY SCHOOLS Community schools, out-of-school-time programs (learning opportunities that take place outside the typical school day), and wraparound services have long existed, separately, in order to meet the needs of Baltimore youth and families. In the early 2000s, these various efforts were uncoordinated, which limited their impact. In 2012, the mayor’s office and Baltimore City Public Schools (BCPS) adopted the Family League of Baltimore’s Community and School Engagement strategy to align the resources and goals of the schools and community. The strategy engaged community-based organizations, such as Elev8 Baltimore and the Y in Central Maryland, to coordinate community school and out-of-school-time efforts. Today, BCPS has approximately 50 community schools engaging with a variety of community partners. The Family League (http:// familyleague.org/), a Baltimore-based nonprofit organization, currently manages funding, partnerships and development, as well as convenes the community school initiative coordinating community partners at the city level. Marietta English, president of the Baltimore Teachers Union (BTU) (http://www.baltimoreteachers.org/), and her members play a key role at school sites as well as at the district and city levels, helping serve the whole child and helping achieve the city’s community school vision. Baltimore’s public school needs achieving this, because each Education Roundtable that included and assets are as diverse as their school tailors its strategy to the community school staff, families population of 82,000 students, specific needs of the school. and students, as well as politicians, creating a rich set of opportunities local community leaders, and and challenges. -

Investment Firm Tied to Baltimore Ravens Owner Buys South Florida

SOUTH FLORIDA NEW YORK LOS ANGELES CHICAGO NATIONAL TRI-STATE search $ MY ACCOUNT SIGN OUT NEWS % MAGAZINES % RESEARCH % EVENTS % VIDEO % TRD TALKS LIVE ! ! " $ % & 0.48% ! CIGI0.27% ! CLPR1.15%TRENDING:! CWK0.26%Coronavirus" DRH1.04%Commercial! ELS Real0.45% Estate! EQRResidential0.64% ! RealESRT Estate0.08% !CelebrityEXPI13.68% Real !EstateGNL0.60%Multifamily! HOV0.18% ! LTC1.02% " MET2.96% ! MMI0.45% " NMRK1.08% ! Investment firm tied to Baltimore Ravens owner buys South Florida car dealerships for $91M Buyer is the investment firm of Maryland billionaire cousins Jim Davis and Steve Bosciotti TRD MIAMI / By Wade Tyler Millward September 25, 2020 05:30 PM From left: Steve Bisciotti, Jim Davis with Jim and John Arrigo, with 5901 Madison Avenue, Tamarac and 2250 North State Road 7, Margate (Getty, Arrigo Auto Group, Google Maps) UPDATED, Sept. 30, 8:50 a.m.: The family ofce of two Maryland billionaires paid $90.5 million for car dealerships in Margate, Tamarac and West Palm Beach that were owned by Arrigo Automotive Group. A company tied to Hanover, Maryland-based Redwood Capital Investments paid $34.5 million for the Tamarac Dodge, Chrysler, Jeep and Ram dealership at 5901 Madison Avenue in Tamarac. Redwood also paid $30 million for the Arrigo West Palm Beach dealership at 6500 Okeechobee Boulevard. Redwood Capital Investments shares an address with Allegis Group, one of the largest stafng firms in the U.S., founded by cousins Jim Davis and Steve Bisciotti. Multiple media reports identify Redwood as the cousins’ investment firm. Bisciotti is also the owner of the Baltimore Ravens National Football League team. -

Final EPA Technical Support Document for Baltimore, MD And

Baltimore, MD and Washington, DC-MD-VA Nonattainment Areas Final Area Designations for the 2015 Ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standards Technical Support Document (TSD) 1.0 Summary This technical support document (TSD) describes EPA’s final designations of nonattainment for the Baltimore, MD and Washington, DC-MD-VA areas for the 2015 ozone national ambient air quality standards (NAAQS). As described in this document, the Baltimore, MD nonattainment area is located solely within Maryland, while the Washington, DC-MD-VA nonattainment area is comprised of portions of Virginia (VA), Maryland (MD), and the District of Columbia (DC). EPA’s nonattainment designation with respect to Cecil County, MD is contained in a separate TSD for the Philadelphia Area. On October 1, 2015, EPA promulgated revised primary and secondary ozone NAAQS (80 FR 65292; October 26, 2015). EPA strengthened both standards to a level of 0.070 parts per million (ppm). In accordance with Section 107(d) of the Clean Air Act (CAA), whenever EPA establishes a new or revised NAAQS, EPA must promulgate designations for all areas of the country for that NAAQS. Under section 107(d), states were required to submit area designation recommendations to EPA for the 2015 ozone NAAQS no later than 1 year following promulgation of the standards, i.e., by October 1, 2016. Tribes were also invited to submit area designation recommendations. On September 23, 2016, the District of Columbia recommended that the entire District be designated as nonattainment for the 2015 ozone NAAQS. The Commonwealth of Virginia recommended on October 3, 2016 that the counties and cities identified in the second column of Table 1, below, be designated as nonattainment for the 2015 ozone NAAQS. -

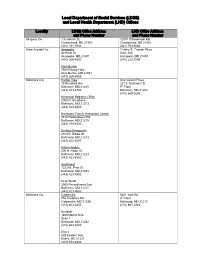

Local Department of Social Services (LDSS) and Local Health Department (LHD) Offices

Local Department of Social Services (LDSS) and Local Health Department (LHD) Offices Locality LDSS Office Address LHD Office Address and Phone Number and Phone Number Allegany Co 1 Frederick St. 12501 Willowbrook Rd. Cumberland, MD 21502 Cumberland, MD 21502 (301) 784-7000 (301) 759-5000 Anne Arundel Co Annapolis 1 Harry S. Truman Pkwy. 80 West St. Suite 200 Annapolis, MD 21401 Annapolis, MD 21401 (410) 269-4500 (410) 222-7095 Glen Burnie 7500 Ritchie Hwy. Glen Burnie, MD 21061 (410) 269-4555 Baltimore City Harbor View One Calvert Plaza 18 Reedbird Ave. 201 E. Baltimore St. Baltimore, MD 21225 9th Floor (443) 423-4700 Baltimore, MD 21202 (410) 649-0500 Northeast Regional Office 2000 N. Broadway Baltimore, MD 21213 (443) 423-6400 Northwest Family Investment Center 5818 Reisterstown Rd. Baltimore, MD 21215 (443) 378-4400 Dunbar-Orangeville 2919 E. Biddle St. Baltimore, MD 21213 (443) 423-5200 Hilton Heights 500 N. Hilton St. Baltimore, MD 21229 (443) 423-4800 Southwest 1223 W. Pratt St. Baltimore, MD 21223 (443) 423-7800 Penn-North 2500 Pennsylvania Ave. Baltimore, MD 21217 (443) 423-7600 Baltimore Co. Catonsville 6401 York Rd. 746 Frederick Rd. 3rd Floor Catonsville, MD 21228 Baltimore, MD 21212 (410) 853-3450 (410) 887-2243 Dundalk 1400 Merritt Blvd. Suite C Baltimore, MD 21222 (410) 853-3400 Essex 439 Eastern Ave. Essex, MD 21221 (410) 853-3800 Locality LDSS Office Address LHD Office Address and Phone Number and Phone Number Baltimore Co. Reisterstown (continued) 130 Chartley Dr. Reisterstown, MD 21136 (410) 853-3010 Towson 6401 York Rd. Baltimore, MD 21212 (410) 853-3340 Calvert County 200 Duke St 975 Solomons Island Rd. -

Baltimore Area Economic Summary

Baltimore area Economic Summary Updated September 07, 2021 This summary presents a sampling of economic information for the area; supplemental data are provided for regions and the nation. Subjects include unemployment, employment, wages, prices, spending, and benefits. All data are not seasonally adjusted and some may be subject to revision. Area definitions may differ by subject. For more area summaries and geographic definitions, see www.bls.gov/regions/economic-summaries.htm. Unemployment rates for the nation and selected Average weekly wages for all industries by county areas Baltimore area, first quarter 2021 (U.S. = $1,289; Area = $1,328) Unemployment rates 10.5 United States 5.7 8.5 Baltimore area 5.4 Anne Arundel Co., 7.6 MD 4.7 Baltimore Co., 8.9 MD 5.5 Baltimore city, 11.5 MD 7.3 7.4 Harford Co., MD 4.9 0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0 Jul-20 Jul-21 Source: U.S. BLS, Local Area Unemployment Statistics. Source: U.S. BLS, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages. Over-the-year changes in employment on nonfarm payrolls and employment by major industry sector Change from Jul. 12-month percent changes in employment Baltimore area employment Jul. 2021 2020 to Jul. 2021 15.0 (number in thousands) Number Percent 10.0 Total nonfarm 1,367.3 62.1 4.8 Mining, logging, and construction 78.9 -1.1 -1.4 5.0 Manufacturing 58.6 1.1 1.9 0.0 Trade, transportation, and utilities 241.8 8.4 3.6 Information 16.8 0.5 3.1 -5.0 Financial activities 76.8 0.4 0.5 -10.0 Professional and business services 246.8 15.5 6.7 Education and health services 265.8 9.6 3.7 -15.0 Leisure and hospitality 118.1 17.1 16.9 Jul-18 Jul-19 Jul-20 Jul-21 Other services 47.0 2.9 6.6 Baltimore area United States Government 216.7 7.7 3.7 Source: U.S. -

DIRECTIONS Directions

WHERE MEETINGS MATTER DIRECTIONS Directions We're Close to Everywhere 695 Beltway Just minutes from Baltimore-Washington International (BWI) Thurgood Marshall Air- port and the BWI Amtrak Train Station, CCMIT offers complimentary shuttle service 95 to and from both locations. Baltimore CCMIT is also accessible throughout the Mid-Atlantic region via I-95, MD-295, and I-695. Once onsite there is free parking for over 600 vehicles. CONFERENCE CENTER AT THE MARITIME INSTITUTE 195 Mass Transit Links CCMIT also has direct rail links to Amtrak and the Maryland MARC trains via the BWI BWI Airport The Baltimore-Washington ® Amtrak Station. Amtrak offers continuous connections along the entire northeast 95 and Amtrak Corridor 100 corridor from Washington, DC to Boston directly to the BWI Amtrak Station. MARC’s 295 2 “Penn Line” provides access to & from Union Station, Washington, D.C., Monday thru 97 495 Beltway Friday. International travelers landing at the Newark International Airport (EWR) have 3 50 the option of using the Amtrak rail line to access the BWI rail station. Dulles Airport IAD Annapolis 24/7 Shuttle Service CCMIT operates a complimentary shuttle service to & from the Baltimore Washington Washington, D.C. International Thurgood Marshall Airport (BWI), The BWI Amtrak Train Station, and the Baltimore Light Rail Station. To access the shuttle, please call 410-859-5700, press 301 Hammonds Ferry Rd. zero, and request a shuttle pick up. Reagan National (Please review the next page for written directions.) Airport DCA CCMIT Campus Map Baltimore/Washington Parkway - 295 B Maritime Blvd. Parking Lot 1 C Building # CCMIT Campus Parking Lot 2 North Building # Residence A Area Overview Tower Parking Lot Residence South Building # Tower 3 BWI Airport and Washington D North Parking Lot Building # Academic 4 Building Academic Maritime Blvd. -

Apartheid Baltimore Style: the Residential Segregation Ordinances of 1910-1913 Garrett Op Wer

Maryland Law Review Volume 42 | Issue 2 Article 4 Apartheid Baltimore Style: the Residential Segregation Ordinances of 1910-1913 Garrett oP wer Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Garrett oP wer, Apartheid Baltimore Style: the Residential Segregation Ordinances of 1910-1913, 42 Md. L. Rev. 289 (1983) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol42/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APARTHEID BALTIMORE STYLE: THE RESIDENTIAL SEGREGATION ORDINANCES OF 1910-1913* GARRETT POWER** On May 15, 1911, Baltimore Mayor J. Barry Mahool, who was known as an earnest advocate of good government, women's sufferage, and social justice, signed into law "lain ordinance for preserving peace, preventing conflict and ill feeling between the white and colored races in Baltimore city, and promoting the general welfare of the city by pro- viding, so far as practicable, for the use of separate blocks by white and colored people for residences, churches and schools."' Baltimore's seg- regation law was the first such law to be aimed at blacks in the United States, but it was not the last. Various southern cities in Georgia, South Carolina, Virginia, North Carolina, and Kentucky enacted similar laws.2 The legal significance of housing segregation laws in the United States was shortlived. -

Reentry Resources by County

Reentry Resources by County Allegany County Harford County Anne Arundel County Howard County Baltimore City Kent County Baltimore County Montgomery County Calvert County Prince George's County Caroline County Queen Anne's County Carroll County Saint Mary's County Cecil County Somerset County Charles County Talbot County Dorchester County Washington County Frederick County Wicomico County Garrett County Worcester County UPDATED GUIDE: www.justice.gov/usao-md Reentry Resources by County County Organization Address Phone Website Alcoholics (301) 722- Allegany Various Locations www.westernmarylandaa.org Anonymous 6110 Allegany County 1 Frederick Street (301) 784- http://dhr.maryland.gov/local- Allegany Department of Cumberland, MD 21502 7000 offices/allegany-county Social Services 12501-12503 Allegany County (301) 759- http://www.alleganyhealthdep Allegany Willowbrook Road S.E. Health Department 5050 t.com Cumberland, MD 21502 Allegany County Human Resources 125 Virginia Ave, (301)777- Allegany Women's www.alleganyhrdc.org Cumberland, MD 21502 8286 Transitional Housing Allegany County P.O. Box 1745 Cumberland, (301) 759- www.marylandbehavioralhea Allegany Mental Health MD 21501 5070 lth.org System Allegany County 138 Baltimore Street, https://mwejobs.maryla (301) 777- Allegany One-Stop Job McMullen Building nd.gov 1221 Center Cumberland, MD 21502 Alternative Drug and Alcohol 994 National Highway (301) 729- Allegany Counseling (ADAC) www.adachelp.org LaVale, MD 21502 0340 of Allegany County (800) 942- www.nationalservice.gov/pro Allegany AmeriCorps Statewide 2677 grams/americorps (301) 683- http://www.amvets.org/amvets- Allegany AMVETS Various Locations 4032 near-you/#map_top 408 N Centre Street (301) 777- Allegany Archway Station www.archwaystationinc.org Cumberland, MD 21502 1700 Baltimore (410) 243- Allegany Neighborhoods, Inc. -

Circuit Court for Baltimore City

CIRCUIT COURT FOR CHARLES COUNTY, MARYLAND COURT REPORTING SERVICES Phone: 301-932-3261 Fax: 301-932-3361 REQUEST FOR COPY OF AUDIO RECORDING (PC compatible only) Date: To: Sondra Graves, Court Reporting Coordinator Charles County Circuit Court 200 Charles Street La Plata, Maryland 20646 CASE NUMBER: CASE NAME: (Only One Case Number Per Form) DATE(S) OF PROCEEDINGS: JUDGE/MAGISTRATE: REQUESTED BY: ADDRESS: CONTACT INFORMATION: PHONE: FAX: EMAIL: Are you a party or an attorney representing a party in this case? YES: NO: Except for proceedings closed pursuant to law, as otherwise provided by rule, or as ordered by the court, Maryland Rule 16-504 provides in part that upon written request and the payment of reasonable costs, the authorized custodian of an official recording shall make a copy of the audio recording available to any person. By my signature, I acknowledge that Maryland Criminal Procedure Article § 1-201 provides that a person may not broadcast any proceeding in a criminal matter and agree that I will not broadcast, copy, transfer, or otherwise electronically transmit to any person any recording of any criminal proceeding, and that any willful violation may be punishable as contempt. SIGNATURE OF THE REQUESTOR: Note: Official CDs generated from the original master recording are provided for listening purposes and verification of testimony only. They may not be used as the official court record in the place of a transcript. Transcripts cannot be produced using CDs. Only transcripts prepared and certified by the court’s approved transcriptionists are deemed official and can be admitted as evidence. Audio recordings are $25.00 per hearing date.