Report on Standardizing Operating Procedures in Ethics Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Data Science in Maritime and City Logistics: Data- Driven Solutions for Logistics and Sustainability

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Jahn, Carlos (Ed.); Kersten, Wolfgang (Ed.); Ringle, Christian M. (Ed.) Proceedings Data Science in Maritime and City Logistics: Data- driven Solutions for Logistics and Sustainability Proceedings of the Hamburg International Conference of Logistics (HICL), No. 30 Provided in Cooperation with: Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH), Institute of Business Logistics and General Management Suggested Citation: Jahn, Carlos (Ed.); Kersten, Wolfgang (Ed.); Ringle, Christian M. (Ed.) (2020) : Data Science in Maritime and City Logistics: Data-driven Solutions for Logistics and Sustainability, Proceedings of the Hamburg International Conference of Logistics (HICL), No. 30, ISBN 978-3-7531-2347-9, epubli GmbH, Berlin, http://dx.doi.org/10.15480/882.3101 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/228915 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Discussion Paper 2019/01 – the Climate Reporting Emergency: a New Zealand Case Study

Discussion Paper 2019/01 – The Climate Reporting Emergency: A New Zealand case study Discussion Paper 2019/01 The Climate Reporting Emergency: A New Zealand case study October 2019 Title Discussion Paper 2019/01 – The Climate Reporting Emergency: A New Zealand case study Published Copyright © McGuinness Institute Limited, October 2019 ISBN – 978-1-98-851820-6 (paperback) ISBN – 978-1-98-851821-3 (PDF) This document is available at www.mcguinnessinstitute.org and may be reproduced or cited provided the source is acknowledged. Prepared by The McGuinness Institute, as part of Project 2058. Research team Wendy McGuinness, Eleanor Merton, Isabella Smith and Reuben Brady Special thanks to Lay Wee Ng and Mace Gorringe Designers Becky Jenkins and Billie McGuinness Editor Ella Reilly For further McGuinness Institute information Phone (04) 499 8888 Level 2, 5 Cable Street PO Box 24222 Wellington 6142 New Zealand www.mcguinnessinstitute.org Disclaimer The McGuinness Institute has taken reasonable care in collecting and presenting the information provided in this publication. However, the Institute makes no representation or endorsement that this resource will be relevant or appropriate for its readers’ purposes and does not guarantee the accuracy of the information at any particular time for any particular purpose. The Institute is not liable for any adverse consequences, whether they be direct or indirect, arising from reliance on the content of this publication. Where this publication contains links to any website or other source, such links are provided solely for information purposes, and the Institute is not liable for the content of such website or other source. Publishing The McGuinness Institute is grateful for the work of Creative Commons, which inspired our approach to copyright. -

BSI Standards Publication

BS EN IEC 62430:2019 BSI Standards Publication Environmentally conscious design (ECD) — Principles, requirements and guidance BS EN IEC 62430:2019 BRITISH STANDARD EUROPEAN STANDARD EN IEC 62430 NORME EUROPÉENNE National foreword EUROPÄISCHE NORM December 2019 This British Standard is the UK implementation of EN IEC 62430:2019. It is identical to IEC 62430:2019. It supersedes BS EN 62430:2009, which ICS 13.020.01 Supersedes EN 62430:2009 and all of its amendments is withdrawn. and corrigenda (if any) The UK participation in its preparation was entrusted to Technical Committee GEL/111, Electrotechnical environment committee. English Version A list of organizations represented on this committee can be obtained on request to its secretary. Environmentally conscious design (ECD) - Principles, This publication does not purport to include all the necessary provisions requirements and guidance of a contract. Users are responsible for its correct application. (IEC 62430:2019) © The British Standards Institution 2020 Published by BSI Standards Limited 2020 Écoconception (ECD) - Principes, exigences et Umweltbewusstes Gestalten (ECD) - Grundsätze, recommandations Anforderungen und Leitfaden ISBN 978 0 580 96347 6 (IEC 62430:2019) (IEC 62430:2019) ICS 13.020.01; 29.020; 31.020; 43.040.10 This European Standard was approved by CENELEC on 2019-11-26. CENELEC members are bound to comply with the CEN/CENELEC Compliance with a British Standard cannot confer immunity from Internal Regulations which stipulate the conditions for giving this European Standard the status of a national standard without any alteration. legal obligations. Up-to-date lists and bibliographical references concerning such national standards may be obtained on application to the CEN-CENELEC This British Standard was published under the authority of the Management Centre or to any CENELEC member. -

Toolkit on Environmental Sustainability for the ICT Sector Toolkit September 2012

!"#"$%&&'()$*+%(,-."/0%1,-*(2- -------!"#"&*+$,-3*4%1*/%15- .*+%(*#-7(/"1A6()B"1,)/5-C%(,%1+'&- D%1-!"#"$%&&'()$*+%(,-- 6.789:;7!<-=9>37-;!6=7-=7- >9.?8@- Toolkit on environmental sustainability for the ICT !"#"$%&&'()$*+%(,-."/0%1,-*(2- -------!"#"&*+$,-3*4%1*/%15- !"#"$%&&'()$*+%(,-."/0%1,-*(2- sector -------!"#"&*+$,-3*4%1*/%15- .*+%(*#-7(/"1A6()B"1,)/5.*+%(*#-7(/"1A-C%(,%1+'&- 6()B"1,)/5-C%(,%1+'&- D%1-!"#"$%&&'()$*+%(,D%1---!"#"$%&&'()$*+%(,-- 6.789:;7!<-=9>37-;!6=7-=7-6.789:;7!<-=9>37-;!6=7-=7- >9.?8@- >9.?8@- Toolkit on environmental sustainability for the ICT sector Toolkit September 2012 About ITU-T and Climate Change: itu.int/ITU-T/climatechange/ Printed in Switzerland Geneva, 2012 E-mail: [email protected] Photo credits: Shutterstock® itu.int/ITU-T/climatechange/ess Acknowledgements This toolkit was developed by ITU-T with over 50 organizations and ICT companies to establish environmental sustainability requirements for the ICT sector. This toolkit provides ICT organizations with a checklist of sustainability requirements; guiding them in efforts to improve their eco-efficiency, and ensuring fair and transparent sustainability reporting. The toolkit deals with the following aspects of environmental sustainability in ICT organizations: sustainable buildings, sustainable ICT, sustainable products and services, end of life management for ICT equipment, general specifications and an assessment framework for environmental impacts of the ICT sector. The authors would like to thank Jyoti Banerjee (Fronesys) and Cristina Bueti (ITU) who gave up their time to coordinate all comments received and edit the toolkit. Special thanks are due to the contributory organizations of the Toolkit on Environmental Sustainability for the ICT Sector for their helpful review of a prior draft. -

2. Sustainable Public Procurement (Spp)

Master Integrating sustainability standards into public procurement process : a comparative analysis between Germany and Viet nam LAMBERT, Siti Rubiah Abstract Integrating sustainability standards into public procurement process - a comparative analysis between Germany and Viet Nam Reference LAMBERT, Siti Rubiah. Integrating sustainability standards into public procurement process : a comparative analysis between Germany and Viet nam. Master : Univ. Genève, 2020 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:132372 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Masters in Standardization, Social Regulation and Sustainable Development Faculty of Social Sciences – University of Geneva Master Thesis Integrating Sustainability Standards into Public Procurement Process A comparative analysis between Germany and Viet Nam Submitted by LAMBERT, Siti Rubiah Under the supervision of: Professor Reinhard Weissinger University of Geneva / ISO Geneva School of Social Sciences Second Reader: Santiago FernandezdeCordoba Senior Economist/ Trade Expert United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) I certify that the work presented here is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original and the result of my own investigations, except as acknowledged, and has not been submitted, either in part or whole, for a degree at this or any other University. 7 January 2020 1 Masters in Standardization, Social Regulation and Sustainable Development Faculty of Social Sciences – University of Geneva Master Thesis -

Standardization Framework for Sustainability from Circular Economy 4.0

sustainability Article Standardization Framework for Sustainability from Circular Economy 4.0 María Jesús Ávila-Gutiérrez * , Alejandro Martín-Gómez, Francisco Aguayo-González and Antonio Córdoba-Roldán Design Engineering Dept, University of Seville, Escuela Politécnica Superior, Virgen de África 7, 41011 Seville, Spain; [email protected] (A.M.-G.); [email protected] (F.A.-G.); [email protected] (A.C.-R.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 8 October 2019; Accepted: 15 November 2019; Published: 18 November 2019 Abstract: The circular economy (CE) is widely known as a way to implement and achieve sustainability, mainly due to its contribution towards the separation of biological and technical nutrients under cyclic industrial metabolism. The incorporation of the principles of the CE in the links of the value chain of the various sectors of the economy strives to ensure circularity, safety, and efficiency. The framework proposed is aligned with the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development regarding the orientation towards the mitigation and regeneration of the metabolic rift by considering a double perspective. Firstly, it strives to conceptualize the CE as a paradigm of sustainability. Its principles are established, and its techniques and tools are organized into two frameworks oriented towards causes (cradle to cradle) and effects (life cycle assessment), and these are structured under the three pillars of sustainability, for their projection within the proposed framework. Secondly, a framework is established to facilitate the implementation of the CE with the use of standards, which constitute the requirements, tools, and indicators to control each life cycle phase, and of key enabling technologies (KETs) that add circular value 4.0 to the socio-ecological transition. -

Standards News Late March 2012 Volume 16, Number 6

PLASA Standards News Late March 2012 Volume 16, Number 6 Table of Contents Eight PLASA Standards in Public Review.........................................................................................................1 RDM and sACN Developers Conference and Plugfest Invitation......................................................................3 ANSI Seeks Comments on ISO Traffic Safety Management Proposal.............................................................3 WTO Notifications............................................................................................................................................. 3 Togo Notification TGO/2................................................................................................................................ 3 Ukraine Notification UKR/72.......................................................................................................................... 4 Uganda Notification UGA/217....................................................................................................................... 4 ANSI Public Review Announcements...............................................................................................................5 Due 23 April 2012.......................................................................................................................................... 5 Due 30 April 2012.......................................................................................................................................... 5 Due 8 May -

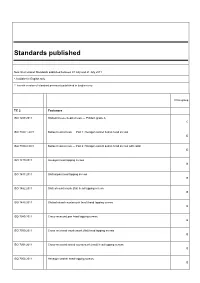

Standards Published

Standards published New International Standards published between 01 July and 31 July 2011 * Available in English only ** French version of standard previously published in English only Price group TC 2 Fasteners ISO 1207:2011 Slotted cheese head screws — Product grade A C ISO 7380-1:2011 Button head screws — Part 1: Hexagon socket button head screws D ISO 7380-2:2011 Button head screws — Part 2: Hexagon socket button head screws with collar D ISO 1479:2011 Hexagon head tapping screws B ISO 1481:2011 Slotted pan head tapping screws B ISO 1482:2011 Slotted countersunk (flat) head tapping screws B ISO 1483:2011 Slotted raised countersunk (oval) head tapping screws B ISO 7049:2011 Cross-recessed pan head tapping screws B ISO 7050:2011 Cross-recessed countersunk (flat) head tapping screws B ISO 7051:2011 Cross-recessed raised countersunk (oval) head tapping screws B ISO 7053:2011 Hexagon washer head tapping screws B TC 5 Ferrous metal pipes and metallic fittings ISO 7186:2011 * Ductile iron products for sewerage applications R ISO 7005-1:2011 * Pipe flanges — Part 1: Steel flanges for industrial and general service piping systems E TC 6 Paper, board and pulps ISO 12625-1:2011 * Tissue paper and tissue products — Part 1: General guidance on terms R TC 8 Ships and marine technology ISO 28002:2011 * Security management systems for the supply chain — Development of resilience in the supply chain — Requirements with guidance for use U TC 20 Aircraft and space vehicles ISO 22072:2011 * Aerospace — Electrohydrostatic actuator (EHA) — Characteristics -

A Review of the Landscape of Guidance, Tools and Standards For

ICSI Guidance, tools and standards Action Track | Position paper JULY, 2021 A Review of the Landscape of Guidance, Tools and Standards for Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure 2 A REVIEW OF THE LANDSCAPE OF GUIDANCE, TOOLS AND STANDARDS FOR SUSTAINABLE AND RESILIENT INFRASTRUCTURE ABOUT ICSI The International Coalition for Sustainable Infrastructure (ICSI) was founded in 2019 by The Resilience Shift, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) and its ASCE Foundation, the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE), the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy (GCoM), WSP and LA Metro, among others. It aims to bring together the entire value chain of infrastructure and unlock the opportunity of using engineers as a driving force for positive impact. It will give engineers a voice in ensuring that we pick the right infrastructure projects to fund and then design and build them with resilience in mind from the outset to ensure safe, sustainable and resilient infrastructure for all our futures. ICSI delivers industry change by engaging members and their organisations through Action Tracks that seek to understand the gaps and barriers to the development of sustainable and resilient infrastructure. ICSI responds with specific actions to address these challenges, and engages stakeholders who are instrumental in delivering actions and adopting new resources, practices and behaviours. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Cover image: Bixby Creek Bridge, also known Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ as Bixby Canyon Bridge, on the Big Sur coast of CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the California, USA (by Darpan Dodiya, Unsplash.com) original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. -

Alphabetical Index

ALPHABETICAL INDEX A Abbreviations Activities relevant to metrics, rubber compounding ingredients 1367 performance metrics SLS ISO/TS 37151 plastics 1559 smart community infrastructures 1507 Abrasive paper 844 Adaptors, bayonet cap 164 Absorbent cotton 285, 1414 Additive elements in lubricating oils gauze 1414 SLS ASTM D 4684 lint 337 Adhesion testers SLS ASTM D4541 viscose gauze 1414 Adhesives Absorbing blood sodium polyacrylate resin 1650-1& 2 ceramic tile 1375 a.c. paper 660 air-break circuit-breakers 1175 polyvinyl acetate based 869 cartridge fuse links 1552 test method SLS ISO 13007-2 electronic control gear 1645-1 & 2 Adjustable ball cup 462 output, stabilized power supplies 1128 Admixtures, ac/dc supplied electronic ballast concrete, mortar, grout EN 934-1 d.c. out put, power supplies 992 conformity, marking, labelling EN 934-2, EN 934-3, tubular fluorescent lamps 1239 Acceptance Quality limit (AQL)(sampling schemes) EN 934-4, EN 934-5 double sampling SLS ISO 3951-3 sampling EN 934-6 single sampling SLS ISO 3951-2single quality Adventure tourism safety management systems SLS ISO characteristic and single SLS ISO 3951-1 21101 declared quality levels SLS ISO 3951-4 Aerated water, glass bottles for 291 inspection variables SLS ISO 3951-5 Aerials Accessories fitted to LPG container 1215 Acetate yarn, gelatin & oil size in 174 sound reception 1008 (withdrawn) Acetic acid salt spray (AASS) test SLS ISO 9227 TV broadcasting 1008 (withdrawn) Acetylene, dissolved 666 Aflatoxin , in food, methods of test 962 Acid After-shave lotion 1031 -

Training Handbook: Sustainable Construction Imprint Title: Training Handbook: Sustainable Construction

Training Handbook: Sustainable Construction Imprint Title: Training Handbook: Sustainable Construction Authors: Wuppertal Institut - Gokarakonda, Sriraj Moore,Christopher Published: Wuppertal Institute 2018 Project title: SusBuild - Up-scaling and mainstreaming sustainable building practices in western China Work Package: 1 Funded by: European Commision Contact: Chun Xia-Bauer Doeppersberg 19 42103 Wuppertal (Germany) e-mail: [email protected] SUSBUILD Training Handbook for Sustainable Construction Table of contents Table of contents 1 Introduction 6 1.1 Sustainable construction 6 1.1.1 Dimensions of Sustainability 6 1.1.2 Sustainable Construction Phase 7 2 Policies, labelling systems and standards related to sustainable construction in Europe 9 2.1 Technical standards related to green construction in Europe 9 2.1.1 European Level 9 2.1.2 CEN/TC 350 - Sustainability of construction works 9 2.1.2.1 EN 15643-1:2010 - Sustainability assessment of buildings - Part 1: General framework 11 2.1.2.2 EN 15643-2:2011 - Assessment of buildings - Part 2: Framework for the assessment of environmental performance 11 2.1.2.3 EN 15643-3:2012 - Assessment of buildings. Framework for the assessment of social performance 11 2.1.2.4 EN 15643-4:2012 - Assessment of buildings. Framework for the assessment of economic performance 12 2.1.2.5 EN 15978:2011 - Assessment of environmental performance of buildings. Calculation method 12 2.1.2.6 EN 16309:2014 - Assessment of social performance of buildings – Methods 12 2.1.2.7 EN 16627:2015 - Assessment of economic performance of buildings - Calculation methods 13 2.1.2.8 EN 15804:2012+A1:2013 - Environmental product declarations. -

Universidad De Oviedo Doctorado En Economía Y Empresa Tesis Doctoral Implicaciones En La Gestión Estratégica De Las Empresas

UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO DOCTORADO EN ECONOMÍA Y EMPRESA TESIS DOCTORAL IMPLICACIONES EN LA GESTIÓN ESTRATÉGICA DE LAS EMPRESAS DE LA INTEGRACIÓN DE LOS SISTEMAS DE GESTIÓN DE LA CALIDAD, MEDIO AMBIENTE Y SEGURIDAD Y SALUD LABORAL, BASADOS EN ESTÁNDARES INTERNACIONALES. EL CASO DE ECUADOR. AUTORA: MARCIA ALMEIDA GUZMÁN DIRECTOR: DR. FRANCISCO JAVIER IGLESIAS RODRÍGUEZ 2018 RESUMEN DEL CONTENIDO DE TESIS DOCTORAL 1.- Título de la Tesis Español/Otro Idioma: Inglés: IMPLICACIONES EN LA GESTIÓN IMPLICATIONS OF QUALITY, ESTRATÉGICA DE LAS EMPRESAS DE LA ENVIRONMENT AND SAFETY AND WORK INTEGRACIÓN DE LOS SISTEMAS DE HEALTH IMSs BASED ON INTERNATIONAL GESTIÓN DE LA CALIDAD, MEDIO STANDARDS, IN THE STRATEGIC AMBIENTE Y SEGURIDAD Y SALUD MANAGEMENT OF FIRMS. THE CASE OF LABORAL, BASADOS EN ESTÁNDARES ECUADOR. INTERNACIONALES. EL CASO DE ECUADOR. 2.- Autor Nombre: DNI/Pasaporte/NIE: Marcia Almeida Guzmán Programa de Doctorado: Programa de Doctorado en Economía y Empresa Órgano responsable: Comisión Académica del Programa de Doctorado RESUMEN (en español) El propósito de esta investigación es el de estudiar las consecuencias que se derivan en la gestión estratégica de las organizaciones ecuatorianas, en un proceso de integración de los sistemas de gestión de Calidad, Medio Ambiente y Seguridad y Salud Laboral, basados en estándares internacionales. Con el fin de lograr encontrar la evidencia (Reg.2018) empírica de la experiencia particular de dichas organizaciones, se aplica un método deductivo hipotético que parte en primer lugar del análisis del soporte teórico así como 010 - del estudio de los sistemas de gestión certificables más ampliamente implantados a nivel mundial (ISO 9001, ISO 14001 y OHSAS 18001, actualmente en proceso de VOA - migración hacia la ISO 45001) junto con los procesos más habitualmente utilizados en su integración.