The First Berkeley Meeting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A TRIBUTE in LOVING MEMORY Irina Diana Tarabac

A TRIBUTE IN LOVING MEMORY Irina Diana Tarabac (1970-2007) Irina Diana Tarabac dedicated her life to learning, teaching, and science – the field of her choice being linguistics. Among many brilliant scholars and scientists in the Linguistics Department at Stony Brook University, Irina stood out for many a reasons. Unfortunately, Irina left us too early in October 2007. After arriving to study at Stony Brook at 2002, Irina became an active member of the linguistic community in the metropolitan area of New York. She frequently attended seminars in the Linguistics Departments of NYU and the CUNY Graduate Center. Irina was dedicated to life-long learning, and she set extremely high standards for herself, her own research and her teaching responsibilities. She taught a morphology seminar in Bucharest and served as a TA for classes on many different topics at Stony Brook, including syntax, morphology, language philosophy, phonology, typology, and Semitic languages. She was a wonderful teacher and was very concerned about her students. Her dedication to linguistics didn’t leave her much time to pursue her hobbies, but whenever Irina found some time off, she enjoyed listening to symphonic music, reading good literature, visiting museums, and spending time with her friends. Irina earned a Master’s degree in Bucharest, Romania in 1996 and had studied and conducted research in the Netherlands between 1997 and 1999. Irina conducted research on well-known languages such as Dutch, Romanian, and Modern Greek as well as less-known languages such as Rapanui and Burushaki. Irina’s passing is a great loss to her family, her friends and the field of linguistics. -

Best Practices in Justifying Calibrations for Dating Language

Journal of Language Evolution, 2020, 17–38 doi: 10.1093/jole/lzz009 Advance Access Publication Date: 28 December 2019 Research article Best practices in justifying calibrations for dating Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jole/article/5/1/17/5688948 by Uppsala Universitetsbibliotek user on 16 October 2020 language families L. Maurits *,†, M. de Heer‡, T. Honkola§, M. Dunn**, and O. Vesakoski§ †Department of Geography and Geology, University of Turku, Turku, Finland, ‡Department of Modern Languages, Finno-Ugric Languages, University of Uppsala, Uppsala, Sweden, §Department of Biology, University of Turku, Turku, Finland and **Department of Linguistics and Philology, University of Uppsala, Uppsala, Sweden *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The use of computational methods to assign absolute datings to language divergence is receiving renewed interest, as modern approaches based on Bayesian statistics offer alternatives to the discred- ited techniques of glottochronology. The datings provided by these new analyses depend crucially on the use of calibration, but the methodological issues surrounding calibration have received compara- tively little attention. Especially, underappreciated is the extent to which traditional historical linguistic scholarship can contribute to the calibration process via loanword analysis. Aiming at a wide audi- ence, we provide a detailed discussion of calibration theory and practice, evaluate previously used calibrations, recommend best practices for justifying calibrations, and provide -

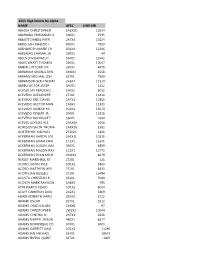

15E5 Ssgt Selects by Alpha

15E5 SSgt Selects by Alpha NAME AFSC LINE-NR ABADIA CHRISTOPHER 2A5X2D 10234 ABARAWA EMMANUEL K 3S0X1 1595 ABBOTT DANIEL PATR 2A7X3 10224 ABDULLAH MALIZIO J 3P0X1 7420 ABENDROTH MARIE CH 00XXX 11386 ABESAMIS CHAMAL JA 2S0X1 44 ABLES LOVIEANGELO 3S0X1 11062 ABLES WYATT THOMAS 2S0X1 10007 ABNER CLIFFORD LEE 3P0X1 4479 ABRAHAM SHARLA DEN 3M0X1 3558 ABRAMS MICHAEL JOH 3E7X1 7500 ABRAMSON SETH NEWM 2A6X4 11510 ABREU VICTOR JOSEP 3P0X1 1412 ACASIO JAY PEROCHO 1P0X1 8032 ACEVEDO ALEXANDER 2T3X1 11416 ACEVEDO ERIC DAVID 2A7X1 12965 ACEVEDO HECTOR MAN 1A0X1 11303 ACEVEDO JANIECE PA 3D0X1 13070 ACEVEDO ROBERT JR 2F0X1 11918 ACEVEDO RODRIGUEZ 3S0X1 2680 ACEVES ULYSSES ALE 2A3X4A 1056 ACHESON SHON THOMA 2A8X2B 5382 ACHTERHOF MICHAEL 2T3X2C 1821 ACKERMAN AARON JOS 2A3X3L 10231 ACKERMAN ADAM CRAI 1C1X1 11641 ACKERMAN LOGAN JAM 3P0X1 8889 ACKERMAN MASON RAY 1C3X1 12772 ACKERMAN RYAN MICH 2M0X3 8079 ACKLEY MARSHALL RY 2T2X1 321 ACORD JUSTIN KYLE 3D1X2 5960 ACORD MATTHEW WILL 2T2X1 5433 ACORN IAN RUSSELL 2T1X1 12494 ACOSTA CHRISTIAN R 3E3X1 7080 ACOSTA MARK RAYMON 2A6X2 495 ACRI MARCO ELIGIO 3D1X2 8009 ACUFF CAMERON DAVI 2A2X1 6869 ADAIR KENNETH HARO 3D0X2 8722 ADAME OSCAR 3E7X1 1512 ADAMS CHAD KALANI 2A6X6 97 ADAMS CHRISTOPHER 2W1X1 10004 ADAMS CYNTHIA N 2A7X3 2658 ADAMS DARRYL JEMON 4B0X1 5627 ADAMS DOMINIQUE CO 3P0X1 3003 ADAMS GARRETT DAVI 3D1X3 11290 ADAMS IAN MICHAEL 3E4X1 10643 ADAMS IRVING QUINT 3E7X1 3407 ADAMS JAMES COLBY 2T3X1 2522 ADAMS JASON ROBERT 1U0X1 7795 ADAMS JOSEPH AARON 2A9X2E 2595 ADAMS KEITH JR 3P0X1 2642 ADAMS KYLE EDWARD 3D0X2 -

A Concise History of English a Concise Historya Concise of English

A Concise History of English A Concise HistoryA Concise of English Jana Chamonikolasová Masarykova univerzita Brno 2014 Jana Chamonikolasová chamonikolasova_obalka.indd 1 19.11.14 14:27 A Concise History of English Jana Chamonikolasová Masarykova univerzita Brno 2014 Dílo bylo vytvořeno v rámci projektu Filozofická fakulta jako pracoviště excelentního vzdě- lávání: Komplexní inovace studijních oborů a programů na FF MU s ohledem na požadavky znalostní ekonomiky (FIFA), reg. č. CZ.1.07/2.2.00/28.0228 Operační program Vzdělávání pro konkurenceschopnost. © 2014 Masarykova univerzita Toto dílo podléhá licenci Creative Commons Uveďte autora-Neužívejte dílo komerčně-Nezasahujte do díla 3.0 Česko (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 CZ). Shrnutí a úplný text licenčního ujednání je dostupný na: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/cz/. Této licenci ovšem nepodléhají v díle užitá jiná díla. Poznámka: Pokud budete toto dílo šířit, máte mj. povinnost uvést výše uvedené autorské údaje a ostatní seznámit s podmínkami licence. ISBN 978-80-210-7479-8 (brož. vaz.) ISBN 978-80-210-7480-4 (online : pdf) ISBN 978-80-210-7481-1 (online : ePub) ISBN 978-80-210-7482-8 (online : Mobipocket) Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................4 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................5 Abbreviations and Symbols ...................................................................................6 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................7 -

English Versions of Foreign Names

ENGLISH VERSIONS OF FOREIGN NAMES Compiled by: Paul M. Kankula ( NN8NN ) at [email protected] in May-2001 Note: For non-profit use only - reference sources unknown - no author credit is taken or given - possible typo errors. ENGLISH Czech. French German Hungarian Italian Polish Slovakian Russian Yiddish Aaron Aron . Aaron Aron Aranne Arek Aron Aaron Aron Aron Aron Aron Aronek Aronos Abel Avel . Abel Abel Abele . Avel Abel Hebel Avel Awel Abraham Braha Abram Abraham Avram Abramo Abraham . Abram Abraham Bramek Abram Abrasha Avram Abramek Abrashen Ovrum Abrashka Avraam Avraamily Avram Avramiy Avarasha Avrashka Ovram Achilies . Achille Achill . Akhilla . Akhilles Akhilliy Akhylliy Ada . Ada Ada Ara . Ariadna Page 1 of 147 ENGLISH VERSIONS OF FOREIGN NAMES Compiled by: Paul M. Kankula ( NN8NN ) at [email protected] in May-2001 Note: For non-profit use only - reference sources unknown - no author credit is taken or given - possible typo errors. ENGLISH Czech. French German Hungarian Italian Polish Slovakian Russian Yiddish Adalbert Vojta . Wojciech . Vojtech Wojtek Vojtek Wojtus Adam Adam . Adam Adam Adamo Adam Adamik Adamka Adi Adamec Adi Adamek Adamko Adas Adamek Adrein Adas Adamok Damek Adok Adela Ada . Ada Adel . Adela Adelaida Adeliya Adelka Ela AdeliAdeliya Dela Adelaida . Ada . Adelaida . Adela Adelayida Adelaide . Adah . Etalka Adele . Adele . Adelina . Adelina . Adelbert Vojta . Vojtech Vojtek Adele . Adela . Page 2 of 147 ENGLISH VERSIONS OF FOREIGN NAMES Compiled by: Paul M. Kankula ( NN8NN ) at [email protected] in May-2001 Note: For non-profit use only - reference sources unknown - no author credit is taken or given - possible typo errors. ENGLISH Czech. French German Hungarian Italian Polish Slovakian Russian Yiddish Adelina . -

C. T. Bauer College of Business

TY OF H SI O R U E S T V I O N N U f o 7 u 2 nded 19 C. T. Bauer College of Business Convocation Friday, December 18, 2015 OF HO Y US T T I O S N R E V I 7 N U 2 9 f 1 ounded Letter from the Dean Dear graduates, Today, you join the ranks of nearly 60,000 alumni of the C. T. Bauer College of Business. As you celebrate your graduation, know that your degree has great value. In fulfilling the requirements of your program, you have demonstrated not only your academic capability, but also the personal discipline and commitment necessary to complete such an educational endeavor. I personally congratulate you on this achievement. Bauer College is more than a degree-granting institution. Yes, to begin with, it is a college of business. On a bigger dimension, I firmly believe this is a place where we change lives and make a difference. We do this by helping our students learn, gain confidence, develop support networks and create opportunity for themselves and for others around them. I am very blessed to see this happen firsthand – to see you all learn, grow and succeed as you use the life skills you learn at Bauer – this is the best part of my job. I hope this convocation marks the beginning of a lifelong relationship with the Bauer College of Business, as well as a successful continued pursuit of your personal education and development. The Bauer faculty and staff are proud to join your family and friends in honoring your accomplishment. -

Odonatological Abstract Service

Odonatological Abstract Service published by the INTERNATIONAL DRAGONFLY FUND (IDF) in cooperation with the WORLDWIDE DRAGONFLY ASSOCIATION (WDA) Editors: Dr. Klaus Reinhardt, Dept Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TN, UK. Tel. ++44 114 222 0105; E-mail: [email protected] Martin Schorr, Schulstr. 7B, D-54314 Zerf, Germany. Tel. ++49 (0)6587 1025; E-mail: [email protected] Dr. Milen Marinov, 7/160 Rossall Str., Merivale 8014, Christchurch, New Zealand. E-mail: [email protected] Published in Rheinfelden, Germany and printed in Trier, Germany. ISSN 1438-0269 ties were not significantly nested. The faunal similarity with the adjacent island of Tenerife is striking. Six of the 1997 Tenerife species are seemingly absent from Gran Ca- naria, whereas Gran Canaria has 13 species not found 11767. Hahn, N.S.; Agostinho, A.A.; Goitein, R. (1997): in Tenerife. Most of the 22 aquatic insect species in Feeding ecology of curvina Plagioscion squamosissi- Gran Canaria only known from older records, prefer len- mus (Hechel, 1840) (Osteichthyes, Perciformes) in the tic habitats not included in our study. All except one of Itaipu Reservoir and Porto Rico floodplain. Acta limno- the five species endemic to Gran Canaria are consid- logica Brasiliensia 9: 11-22. (in English, with Portugue- ered extinct or on the edge of extinction. Increased fu- se summary) [Fish samplings were carried out from No- ture extinction rates are predicted as a response of the vember 1983 to September 1988, at different sites of extreme habitat loss, with only three permanent streams the Paraná River basin (Brazil), comprising the section known on the island today." (Authors) The following between the Paranapanema and Iguaçu Rivers. -

AMADEI Prof. Giorgio - Bologna 1983 - 1987 - 2002 BACCETTI Prof

ACCADEMICI EMERITI AMADEI prof. Giorgio - Bologna 1983 - 1987 - 2002 BACCETTI prof. Baccio - Siena 1965 - 1985 - 2001 BALDINI prof. Enrico - Bologna 1958 - 1965 - 2000 BOSTICCO prof. Attilio - Torino 1979 - 1987 - 2003 BONCIARELLI prof. Francesco - Perugia 1985 - 1989 - 2004 BONSEMBIANTE prof. Mario - Padova 1968 - 1975 - 2000 CASADEI prof. Ettore - Forlì 1987 – 1991 - 2007 CASATI prof. Dario - Milano 1987 – 1991 - 2007 CAVAZZA prof. Luigi - Bologna 1968 - 1977 - 2000 CHERUBINI prof. Giovanni - Firenze 1987 – 1991 - 2007 CODA NUNZIANTE prof. Giovanni - Siena 1979 - 1980 - 2006 CONTINI BONACOSSI dott. Ugo - Firenze 1966 - 1991 - 2006 CORDERO DI MONTEZEMOLO dott. Massimo - Roma 1983 – 1991 - 2007 DIANA cav. lav. dott. Alfredo - Roma 1970 - 1975 - 2001 DINI prof. Dino - Firenze 1968 - 1972 - 2003 DINI prof. Mario - Firenze 1980 - 1982 - 2005 FAVILLI prof. Ranieri - Pisa 1958 - 1962 - 2000 FERRO prof. Ottone - Padova 1970 - 1975 - 2002 FIORINO prof. Piero - Firenze 1983 - 1989 - 2005 FRESCOBALDI cav. lav. m.se dott. Vittorio - Firenze 1969 - 1975 - 2003 GAETANI D’ARAGONA prof. Gabriele - Napoli 1972 - 1983 - 2006 GALOPPINI prof. Carlo - Pisa 1970 - 1983 - 2001 GIOIA cav. lav. gr. cr. dott. Giuseppe - Palermo 1975 - 1980 - 2001 GROSSI prof. Paolo - Firenze 1965 - 1987 - 2002 LANDI prof. Renzo - Firenze 1966 - 1972 - 2002 LECHI prof. Francesco - Brescia 1982 - 1987 - 2003 LORETI prof. Filiberto - Pisa 1973 - 1983 - 2002 LUCIFERO prof. Mario - Firenze 1969 - 1973 - 2001 MANCINI prof. Fiorenzo - Firenze 1955 - 1965 - 2000 MANFREDI prof. ing. Enzo - Bologna 1970 - 1975 - 2002 MARACCHI prof. Giampiero - Firenze 1977 - 1982 - 2004 1 MARINELLI prof. Augusto - Firenze 1980 - 1990 - 2005 MARZI prof. Vittorio - Bari 1987 – 1991 - 2007 MAZZEI cav. lav. Lapo - Firenze 1975 - 1980 - 2001 MONTEMURRO prof. -

The Germanic Languages

This page intentionally left blank THE GERMANIC LANGUAGES Germanic – one of the largest subgroups of the Indo-European language family – comprises 37 languages with an estimated 470 million speakers worldwide. This book presents a comparative linguistic survey of the full range of Germanic languages, both ancient and modern, including major world languages such as English and German (West Germanic), the Scandi- navian (North Germanic) languages, and the extinct East Germanic lan- guages. Unlike previous studies, it does not take a chronological or a language-by-language approach, organized instead around linguistic con- structions and subsystems. Considering dialects alongside standard varieties, it provides a detailed account of topics such as case, word formation, sound systems, vowel length, syllable structure, the noun phrase, the verb phrase, the expression of tense and mood, and the syntax of the clause. Authoritative and comprehensive, this much-needed survey will be welcomed by scholars and students of the Germanic languages, as well as linguists across the many branches of the field. WAYNE HARBERT is Professor and Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Department of Linguistics, Cornell University. He has published extensively on syntactic topics, with a particular emphasis on historical syntax. His work on Germanic languages covers a wide range of problems in historical Ger- manic syntax and phonology, drawing on data from Gothic, Old English, Old High German, Old Saxon, Old Norse, and Modern German. CAMBRIDGE LANGUAGE SURVEYS General editors P. Austin (SOAS, London) J. Bresnan (Stanford University) B. Comrie (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig) S. Crain (University of Maryland) W. Dressler (University of Vienna) C. -

Graduation 2021 Social Science and Business Technologies Message to the Graduates of Dawson College

Graduation 2021 Social Science and Business Technologies Message to the Graduates of Dawson College Simply congratulating our graduating class of 2021 does not seem sufficient this year. We at Dawson are in awe of what you have overcome to get to this moment. All students have dealt with their own unique challenges in the COVID-19 pandemic. You were kept apart from your friends and extended family and, with the future uncertain, you pushed yourself each day to connect to your classes online, complete your assignments and move forward with your education. Let me tell you now: your perseverance will pay off. We know the events of the last year and a half have tested you. But please remember what you have gained: resilience and determination - key indicators for future success. At Dawson, our goal is not only to educate, but to engage you to become active citizens. We seek to enrich society by offering life-long learning opportunities, cultivating partnerships and contributing to a peaceful and sustainable future. We encourage you to take what you have learned at Dawson and help society build back better. Use your skills to help others, challenge the status quo and build on what this global crisis has accentuated and revealed about the interconnectedness of humanity. On behalf of all Dawson faculty, staff and administration, I would like to share our pride in what you have accomplished and acknowledge your outstanding efforts. Know that from this moment forward, you can be proud to say that you are a Dawson College graduate. Carmela Gumelli Academic Dean of Dawson College 2 3 We know that graduation is an important milestone in your life. -

Anllech an Aolt an Boer an C an Cash an Caskey An

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 08 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 61 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 19.600 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

Iii. Administración Local

BOCM BOLETÍN OFICIAL DE LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID Pág. 154 JUEVES 28 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2013 B.O.C.M. Núm. 283 III. ADMINISTRACIÓN LOCAL AYUNTAMIENTO DE 44 MÓSTOLES OTROS ANUNCIOS Se ha dictado por la concejala-coordinadora del Área de Presidencia Administración Pública, con fecha 3 de octubre de 2013, el siguiente decreto: Vista la comunicación del Instituto Nacional de Estadística, en la que se pone de ma- nifiesto que los extranjeros no comunitarios sin autorización de residencia permanente (ENCSARP) que se indican en la presente resolución, no han procedido a la renovación pa- dronal a la que obliga el artículo 16.1 de la Ley 7/1985, de 2 de abril, Reguladora de Bases del Régimen Local, en su redacción dada por la Ley 14/2003. Considerando que, en cumplimiento de la resolución 28 de abril de 2005, de la presi- denta del Instituto Nacional de Estadística y del director general de Cooperación Local, el alcalde del municipio deberá declarar la caducidad de inscripción y acordar la baja padronal mediante resolución motivada. Considerando que por parte del Departamento de Registro y Estadística se ha procedi- do a poner en conocimiento de los afectados tal circunstancia, con preaviso de caducidad, en cumplimiento del acuerdo 11/103 aprobado en sesión plenaria de 14 de julio de 2005. Resultando que han transcurrido dos años desde su inscripción padronal y no han pro- cedido a su renovación con anterioridad al 30 de septiembre de 2013. Considerando que el artículo 16.1 de la LRBL y la resolución de 28 de abril de 2005, de la presidenta del INE y del director general de Cooperación Local, por la que se dictan instrucciones técnicas para acordar la caducidad de las inscripciones padronales de los ENSCARP que no sean renovadas cada dos años, y en virtud de las competencias delega- das al Área de Coordinación Estratégicas, Institucional y Administración Pública de Presi- dencia, en virtud del decreto de Alcaldía 15/2013, de 10 de enero (BOLETÍN OFICIAL DE LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID número 47, de 25 de febrero de 2013).